The life and legacy of one of the most brilliant and influential guitar instructors who ever lived.

Born: September 26, 1946

Died: July 23, 2005

Best Known For: Ted Greene devoted his life to unlocking the secrets of the guitar’s fretboard and sharing them with whoever wished to learn. His four books—Chord Chemistry, Modern Chord Progressions, and Jazz Guitar Single Note Soloing Volume 1 and Volume 2—have taken literally untold thousands of players through the deepest recesses of guitar theory.

In life we sometimes encounter people who, like Virgil in Dante’s Inferno, guide us along treacherous paths to our ultimate destination. For many on the path to guitar excellence, Ted Greene was that guide.

A heart attack claimed Greene’s life on July 23, 2005, yet he continues to teach through his books, videos, and lesson guides, many of which are posted on his official website, tedgreene.com. Ted Greene was many things: musician, friend, eccentric, mentor, and student. But to many, he was simply a hero.

Moving Torsos

Theodore “Ted” Greene was born September 26, 1946, in Los Angeles, California. Music seemed to be woven into the fabric of his being. His mother recalled her baby rocking back and forth to rhythm from the time he could sit up. His intellect became apparent once he started school. He was a math whiz with an IQ of 160—well into genius territory.

Greene received his first guitar in 1957 at age 11. “I had a horrible guitar with the highest action in the world, especially down at the nut,” he later reminisced. “I almost quit, but my parents’ encouragement and a true love of music carried me through.”

Though he was left-handed, he opted to play right-handed. He took lessons from local jazz guitarist Sal Tardella. Despite his later affinity for the genre, said Greene, “the sounds of rock and roll were pulling my ears.” In 1960 he joined his first band, the Cage Kings, and acquired his first good guitar: a Gretsch 6120. He later admitted he wasn’t ready to play in a group. “But it didn’t matter,” he said, “because we could make a lot of noise. That seemed adequate to get people’s lower torsos moving on the floor.”

Greene didn’t embrace guitar as a lifestyle until after high school. At 19, he’d spend hours—even days—in his bedroom, obsessively expanding his music theory knowledge. As his longtime partner Barbara Franklin wrote in her memoir, My Life with the Chord Chemist, “If a book suggested doing an exercise in a few keys, such as spelling major triads, Ted would do the exercise in all keys, major and minor, until he had memorized them cold. Greene learned to instantly recognize everything from interval identification … to knowing the quality of every chord on each scale degree, the many uses for each chord, the inversions, traditional voice leading, and more.”

Ted Greene with jazz singer Cathy Segal-Garcia circa 1977. Photo courtesy of Leon White

To Teach Is to Love

In 1965, Greene found his calling when he accepted a teaching position at Ernie Ball Guitars in Tarzana, California. “I didn’t mean to be a guitar teacher,” he said, “but I just fell in love with it.” His playing ability and musical knowledge quickly attracted a large pool of prospective students, and soon there was a two-year waiting list to study with him.

Students were drawn to both the method and the man. Hundreds of Greene students will expound at great length on his kindness, patience, humor and generosity. Leon White—a Greene pupil and co-producer of Solo Guitar, Greene’s only solo album—recalled that, “If a guy came in and said, ‘I’m a little short this week and I can only pay you half,’ Ted would say, ‘Well, can you afford that half? Do you want to keep it and pay me some other time?’” In fact, throughout his life, Greene charged criminally low rates for lessons—usually no more than $25 per half hour. He just seemed to love teaching, and he believed that no one should be denied a chance to study with him because they couldn’t afford it.

Meanwhile, Greene continued to gig around Los Angeles with various rock and blues acts. In 1967, he joined a group called Bluesberry Jam that featured future Canned Heat member Adolfo “Fito” de la Parra on drums. The group regularly played the Magic Mushroom club, as well as the larger Shrine Auditorium, where they supported such acts as the Doors, Iron Butterfly, Joe Cocker, and Alice Cooper. While Bluesberry Jam gained a following around the city, they never made it to the next level, and the band folded when de la Parra departed for Canned Heat. Sadly, no Bluesberry Jam recordings survive. However, Greene did record with psychedelic rocker Joe Byrd, including on Byrd’s 1969 album The American Metaphysical Circus.

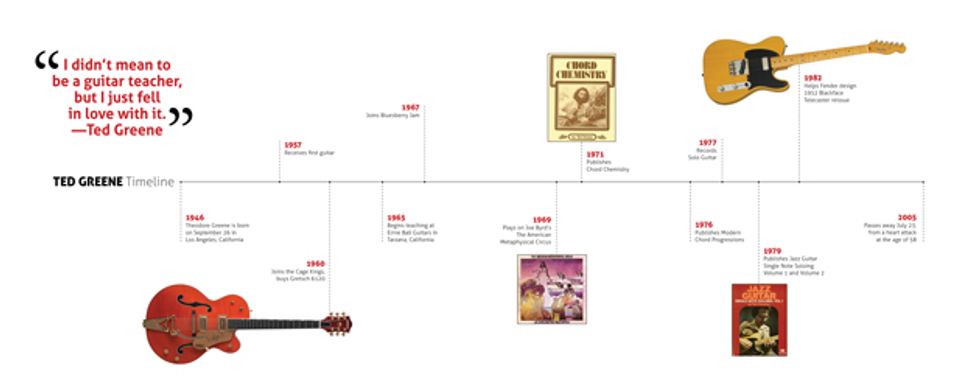

Ted Greene's timeline

Greene then threw himself even deeper into teaching. Simple diagrams he’d previously drawn to demonstrate his concepts grew increasingly more detailed. Barbara Franklin would later recall how he made charts of all closed-voiced triads in all major and minor keys. “On the same page would be a list of the most common chord progressions to be memorized. The page went on to include adding the 6th, 7th, 9th, 11th, and 13th degree to each chord.”

In fact, to say that Greene was systematic in his approach to teaching, playing, and writing music would be an understatement—to some it appeared to border on obsession. Others believe Greene might have suffered from an undiagnosed case of Asperger syndrome—an autism-spectrum disorder that typically affects social interaction and is often accompanied by restrictive or repetitive interests and behaviors. Those who subscribe to this theory believe it explains his later decisions to limit his exposure to the public at large. Franklin notes in her memoir of Greene that, "This thought or that, a moment split by the minds' idle chatter or a tune running through it and a week flies by."

Chord Chemist

Dale Zdenek, owner of the music shop where Greene taught, took note of these minutely detailed diagrams. In 1971, Zdenek, who had no background in publishing, proposed a book based on Greene’s work. Greene was interested, but instead of simply compiling his extant material, he decided to create something completely new.

The resulting book, Chord Chemistry, went on to become essential reading for players seeking a deeper understanding of chords. Its success established Greene’s name in the guitar community, and the desire to study with him and see him perform increased exponentially. In 1976, Greene published a second important chord book, Modern Chord Progressions. (It’s worth noting that while the contents of Greene’s chord books were meant to be absorbed in the order they’re presented, they’re not so much formal methods as encyclopedias of ideas.)

Meanwhile, Greene continued his own studies. He took eight weeks of lessons from the “Father of the 7-String Guitar,” George Van Eps, and worked on expanding his knowledge of single-note playing. In 1979, he published two books on the subject: Jazz Guitar Single Note Soloing Volume 1 and Volume 2.

Greene’s four books offer up a staggering amount of information, including many concepts never before available in print. Even if he’d never done anything else, these volumes would have secured his place in guitar history.

Telecaster Crazy

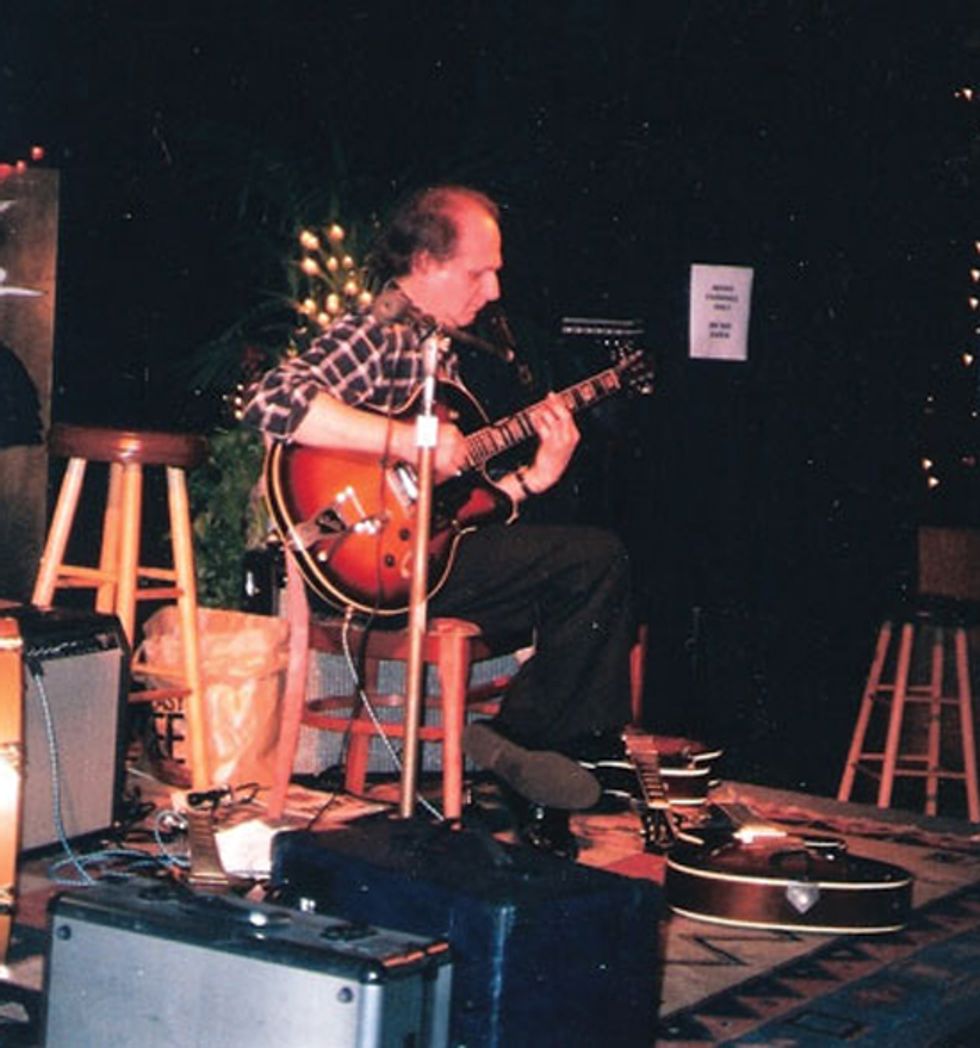

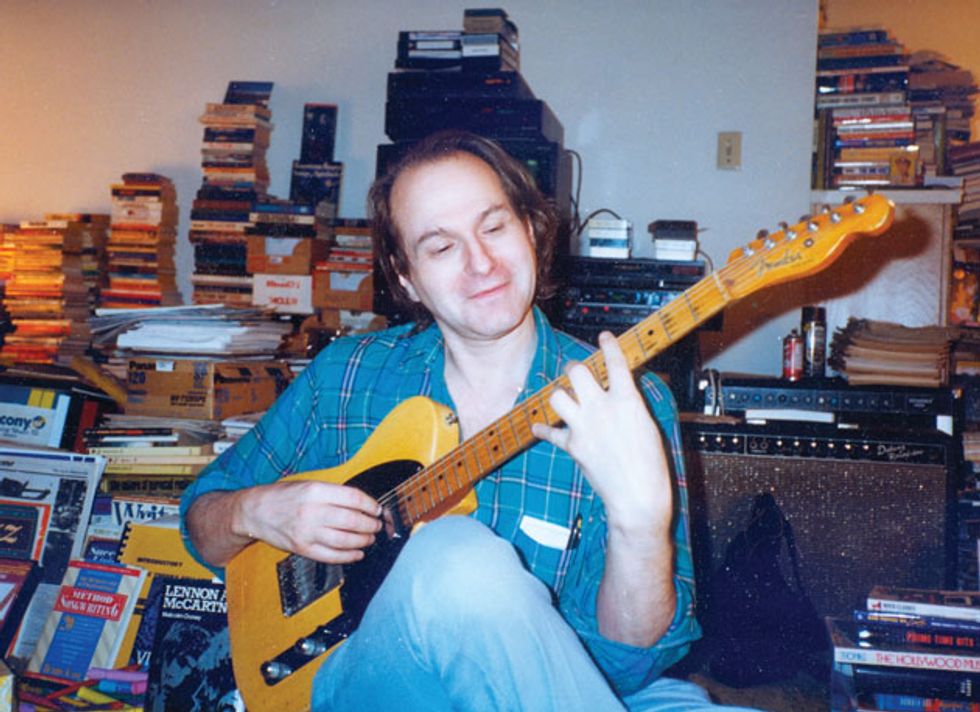

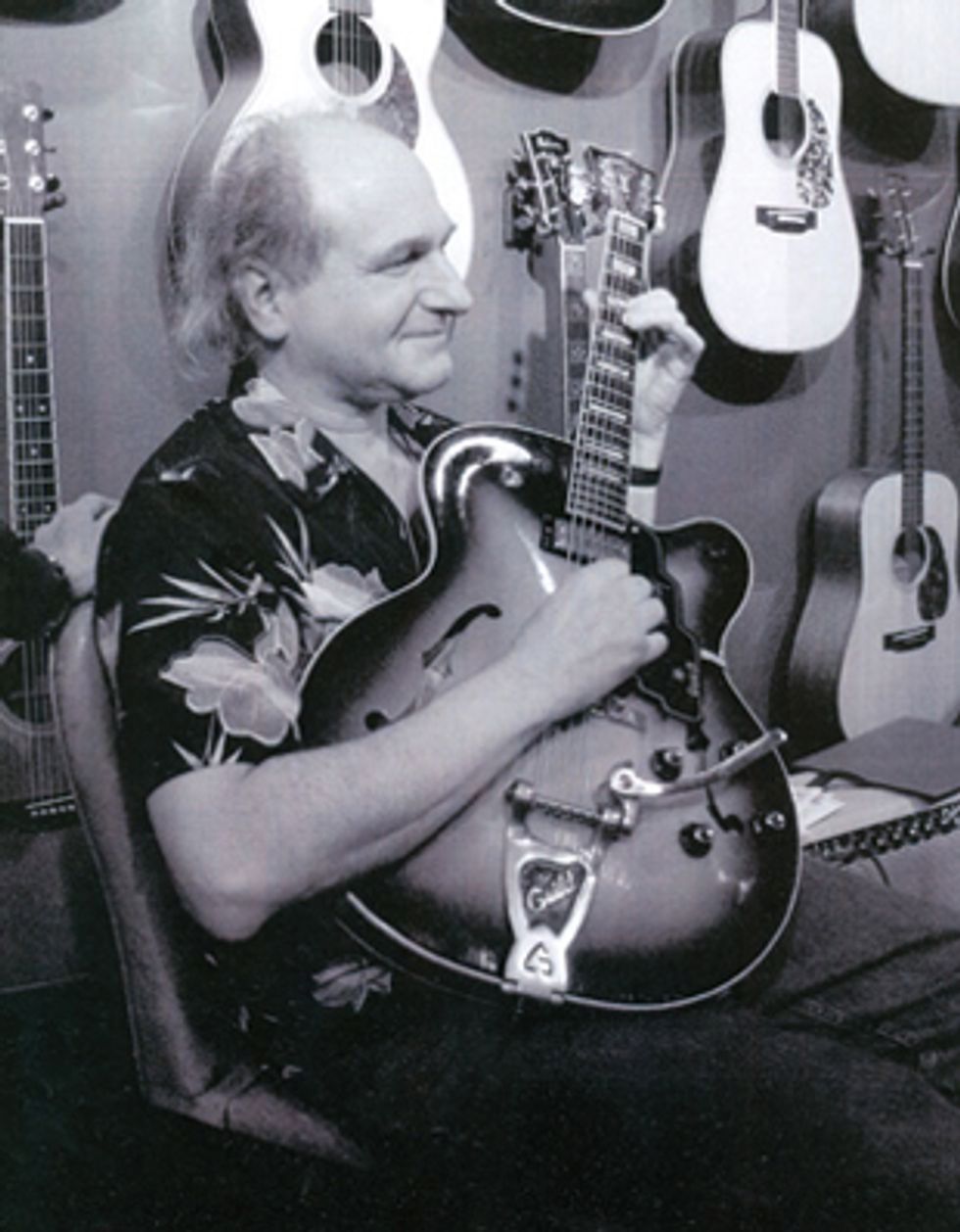

Greene was best known for playing highly modified Telecasters, but he also loved classic Gibson guitars.

Photo courtesy of Leon White

In April of 1965 Greene acquired his first Fender Telecaster, a 1953 that cost $135. It was the beginning of a lifelong love affair with the Tele. Greene estimated that he owned 200 Telecasters at one point or another. “The versatility of the Telecaster is almost unmatched,” he said in an interview.

When Fender decided to manufacture a reissue model of their famed 1952 Blackface Tele, the company turned to Greene and his vast collection while designing the prototype. Greene regularly offered suggestions about how to improve the reissue. Fender asked him to play the new guitars at their 1982 NAMM show debut, which he happily did.

In later years Greene’s favorite Tele was a hybrid: a ’52 body fitted with a ’51 Esquire neck. He routed the body himself, installing two DiMarzio Dual-Sound humbuckers in the neck and middle positions. He also replaced the stock bridge pickup with one from a 1954 model. Interestingly, Greene removed the pole pieces from a pair of stock Gibson humbuckers and installed them into the DiMarzios, which were then set low into the guitar—beneath the pickguard, even—with the pole pieces set high near the strings. His explanation for the unusual parts swapping and positioning was that he did it to “get rid of the mud.” Another uncommon choice was Greene’s choice of rather heavy strings for his Telecasters, including a .013 or sometimes even a .014 for the high E.

While Telecasters held a special place in Green’s heart, he owned many other guitars, mostly Gibsons. His collection included a goldtop Les Paul, an ES-335, and a number of hollowbody archtops.

Photo courtesy of Leon White

Throughout his life Ted Greene preached the gospel of harmony. Everything from blues to Baroque was fair game, and Greene made every chord move a teachable moment. Since his passing, many former students have made his handouts, arrangements, and lesson notes available through tedgreene.com. Nearly all the material consists of scanned versions of actual lesson handouts, and they feature Greene’s unique method for diagramming chords. Many of these documents are signed and dated, and contain what could be thought of as one of Ted’s Musical Commandments: “Don’t let the music die on the page.”

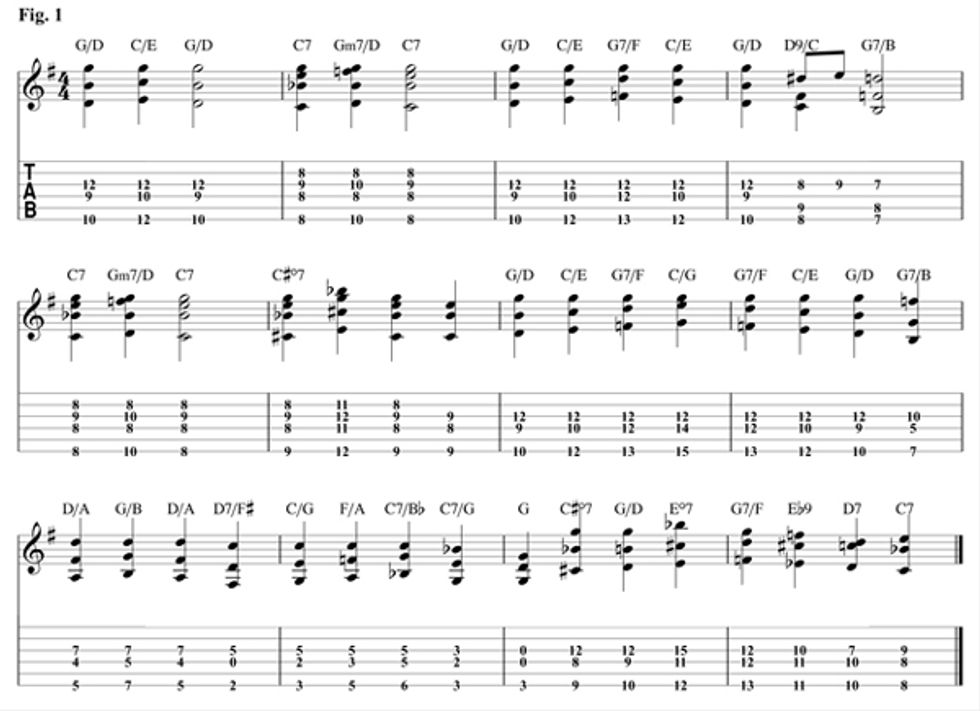

In this lesson we’ll look at two distinctly different (but sublimely “Ted”) ways Greene approached the blues. Fig. 1 is a gospel-influenced blues progression that makes use of many concepts that Greene illustrated in his opus on harmony, Chord Chemistry.

This blues in G starts with a I-IV progression in the first measure to establish the sound of the key. One of the most essential—and amazing—aspects of Greene’s style is his masterful command of voice leading, which is the technique of moving from one chord to another in the most musically economical way possible. To better understand this idea, think of each chord shape as a collection of individual voices rather than a “grip” or “shape.” In the first measure, notice how Greene keeps the common tone (G) on top while moving the lower two notes up to the next closest chord tones.

Creating a smooth and melodic series of chords, while still sticking to a harmonic framework, is like solving a challenging puzzle. In the third and fourth measures, Greene uses a scalar bass line (D–E–F–E–D–C–B) to set up a G7/B chord going into the IV chord (C7). Greene uses a dim7 chord in the next measure to create some tension before returning to the I chord in the sixth measure. A diminished chord is made up of a series of minor third intervals, and this allows any note to function as the root. The scalar bass line technique gets a reprise in measures seven and eight before the progression heads to the V chord in measure nine.

While focusing on economy of motion and outlining the harmony, Greene creates a somewhat symmetrical melody line over the V and IV chords, above the ever-so-slightly shifting the harmony underneath. Finally, in the last two measures he combines the previous diminished harmony with a masterful bass line to create a turnaround that’s as functional as it is sophisticated.

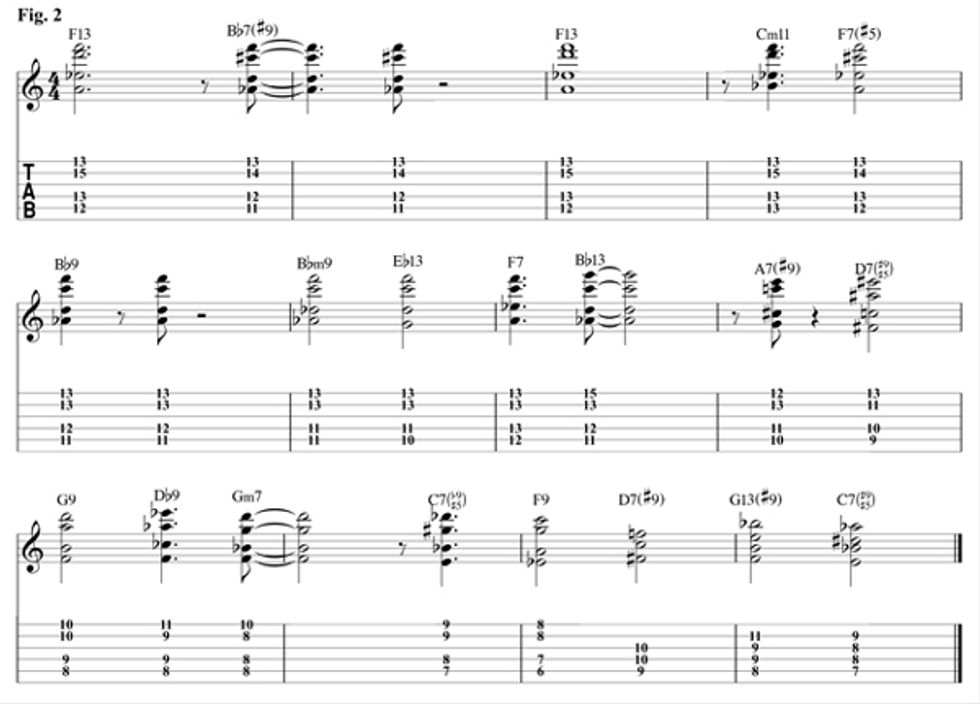

In Fig. 2, we see how Greene combines a traditional form with more extended harmonies and substitutions. The first thing you’ll notice about the voicings is that they’re almost exclusively played on the 5–4–2–1 string set. Greene was a devout fingerstyle player and these “split” voicings will expand your right-hand technique and suggest alternatives to typical jazz grips. When Greene originally presented this material, it was merely a bunch of chord diagrams on a page. Following his advice, I took those chords and added a more syncopated rhythm.

If you look at how Greene constructed these chords, all of them start on either the 3 or 7. Those two notes are the most essential harmonic elements because they define both the chord’s quality and tonality. The first harmonic twist is in the fourth measure where Greene inserts a IIm–V7 progression to create a stronger pull into the Bb9 chord in the next measure. The key changes momentarily to Ab in the sixth measure with a IIm-V7. The Eb13 in measure six keeps two common tones while the harmony gracefully shifts up for a return to the I chord in the next measure.

The eighth measure contains the standard altered VI chord, but this time its own altered V7 precedes it. In harmonic terms, this measure can either be thought of as simply a III7–VI7 progression in the key of F, or an added secondary dominant (V of VI). The final four measures begin with a dom7 chord built on the second degree of the scale. Usually in the blues form this would be a min7 chord, but Greene deftly adds a tritone substitution after this in order to let the lower notes of the chord remain while the upper notes shift. This sets up a proper IIm–V7 progression in the next measure before ending with a I–VI7–II7–V7 turnaround.

Greene's genius survives through his books and recordings—and the hundreds of students whose lives he touched.

Photo courtesy of Leon White

Solo Guitar

In 1976 Greene began performing his first solo gigs, taking up a Sunday night residency at the Smoke House in Toluca Lake, California. Southern California guitarists flocked to hear the master perform. One frequent attendee was Greene’s friend and sometime student Leon White. Recalls White, “In the parking lot after the show I said to him, ‘We have to record that. You don't have to prepare anything. Just come and sit down and play.’ We ended up having that same discussion in the Smoke House parking lot for two years. He just didn’t want to do it!”

Ultimately, White’s persistence won the day, and Greene went into the studio with White and friend William Perry. Over the course of roughly 10 hours spread out over two days, Greene sat alone in the studio, playing almost continuously. There was no game plan, not even a song list—just Greene playing whatever came to mind.

Greene’s uncompromising meticulousness sometimes made for a grueling process. “He played all those songs front to back, so each tune is a single performance,” says White. “He would start up on something, get three and a half minutes into it, not like it, and stop. We were going through reels of tape like you have no idea!”

The result was Solo Guitar, a breathtakingly beautiful set of standards played as only Ted Greene could play them. The album received near-universal praise. “On this record he defies the technical physics of jazz melody chord voicings but creates an organic and inspired listening delight,” Steve Vai told Guitarist magazine. “It’s a must for anyone who puts their fingers on an instrument with strings.” Sadly, Solo Guitar is Green’s only solo release.

A Teacher Affects Eternity

Greene ceased writing instructional books after 1979, though he continued teaching and learning. For the rest of his life, he coached aspiring guitarists at his home, at Musicians Institute in Los Angeles, and at seminars throughout Southern California.

He stopped playing solo gigs, too—reportedly because he disliked the way guitar players would scrutinize his technique and execution on the guitar rather than soaking in the music he drew from the instrument. According to Leon White, Greene often said, “I’d rather play at a retirement home for blue-haired old ladies than at a club. At least the old ladies would listen to and enjoy the music and not watch my hands the whole time.”

When Greene passed away on July 23, 2005, approximately 700 people attended his memorial, nearly all of them guitarists. Greene had many loves in his life: baseball cards, fast cars, and his partner Barbara Franklin. But above all else, he loved music and teaching.

As the noted writer Henry Adams once said, “A teacher affects eternity. He can never tell where his influence stops.” Greene’s legacy may outlive us all.

Ted Greene's Must-Watch Moments

Live footage of Ted Greene is quite rare, but the following three segments on YouTube show the genius in his element as both a performer and an instructor.

Ted Greene performs a masterful and completely improvised performance of the Beatles classic “Eleanor Rigby.”

Greene's performance of “Embraceable You” is a great example of his chord mastery.

Greene doing what he did best: teaching. Lovely examples of classical and jazz pieces throughout.