The Glasgow quintet enters its third decade with stunning creativity—and volume.

Few bands have the staying power of Mogwai, the post-rock group formed two decades ago in Glasgow, Scotland. The mostly instrumental group, which borrows its name from creatures in the movie Gremlins, came together in 1995 when three friends—guitarists Stuart Braithwaite and Dominic Aitchison (now the band’s bassist), along with drummer Martin Bulloch—set out to create some intense guitar music. The trio enlisted an additional guitarist, John Cummings, and in 1996 released the self-pressed single “Tuner”/“Lower,” an oddball in the Mogwai catalog on account of its prominent vocals.

Mogwai added Teenage Fanclub drummer Brendan O’Hare to its lineup and in 1997 came out with a full-length debut, Mogwai Young Team, which established the group as a serious instrumental music quintet that could be both loud and introspective. O’Hare was swapped out for keyboardist Barry Burns, who appeared on Mogwai’s sophomore album, Come on Die Young (1999), and has been with the group ever since.

Mogwai’s third album, Rock Action (2001), added synthesizers and other electronic elements to the mix. The group had arrived at a sound that was large and cinematic—as heard in the 2006 film Zidane: A 21st Century Portrait, for which Mogwai wrote the soundtrack. In 2012 band also contributed brooding, wordless music to Les Revenants, a French television series.

Electronic sounds have remained a Mogwai fixture, appearing on every album through Rave Tapes, the band’s eighth and most recent full-length effort, and their second on Sub Pop. The album was written in the band members’ home studios and recorded in their Castle of Doom studio in Glasgow with producer Paul Savage, who also worked with Mogwai on their first record and on 2011’s Hardcore Will Never Die, But You Will.

While electronics play a prominent role on Rave Tapes, they don’t detract from the many bright guitar moments, from the improvised modal shredding on “Simon Ferocious” to the gritty arpeggios of “Hexon Bogon” to the straightforward, plaintive melodic work on “No Medicine for Regret.”

Braithwaite and Cummings spoke to us about their process, their tools, and their penchant for loudness.

Your music sounds so sophisticated. What sort of formal training do you have?

Stuart Braithwaite: I did a music course at college—more rock than classical—focusing on playing guitar and recording. It’s been very helpful in the fundamental things it taught me about music theory and production, as well as music business things like copyright and ownership—knowledge that has served me well in the band.

John Cummings: I don’t have any formal music training, but our keyboardist, Barry [Burns], is essentially a classically trained pianist. He studied at the Royal Academy of Music [in Glasgow].

What inspired the title Rave Tapes?

SB: This probably dates us—we’re in our late 30s. The title is a reference to the cassettes of rave music that people used to swap when we were teenagers.

JC: The title isn’t too philosophical. We were thinking about what crazy times those were, and it seemed like a great title for a record, though the music isn’t necessarily modeled on what was heard on actual rave tapes of the era.

Talk about your compositional process.

SB: Everyone in our band apart from [drummer] Martin [Bulloch] comes up with ideas on his own, and then we all have a listen together to shape the pieces. All of our approaches vary. Mine are so often quite sketchy. [Laughs.] Some of the others, like Barry’s, tend to be highly detailed, with ideas that are more fully fleshed out.

JC: It’s a bit difficult to describe. Often I play for five minutes to see if I can come up with a kernel of an idea that the band can work with to create a full arrangement. It’s really not too methodical or formulaic.

How does improvisation figure in your recordings and performances?

SB: I’ve always been into improvisation. It’s how I learned to play the guitar, and throughout the years it has always helped keep things fresh. It probably happens more on our recordings than live these days. A lot of my guitar parts on the new record were improvised—mainly through ill preparation! [Laughs.] Every single note on “Simon Ferocious,” for instance, was made up on the spot, and it worked out quite well.

JC: Not so much for me. I might improvise a bit during sessions when recording a rough part, but there’s not really too much of a jamming aspect to my style. Even in some of our longer pieces, I pretty much play each part the same way every time.

Recording has evolved considerably since you started out. Has digital technology impacted your writing process?

SB: It’s made it easier in some ways. Early on, of course, we weren’t able to record on our phones at home—we used cassette 4-tracks, which were obviously much less flexible than the software we use today. Using Logic and Native Instruments on my iMac, it’s easy for me to record demos on my own that sound almost as good as the finished products will.

JC: It’s indeed easier for us these days to work things out on our own in advance. The accessibility and availability of equipment is obviously nice, and it’s just much more efficient to record and edit music. But just as we did with 4-tracks, we still make compositions by layering sound upon sound, so the writing process itself hasn’t really changed.

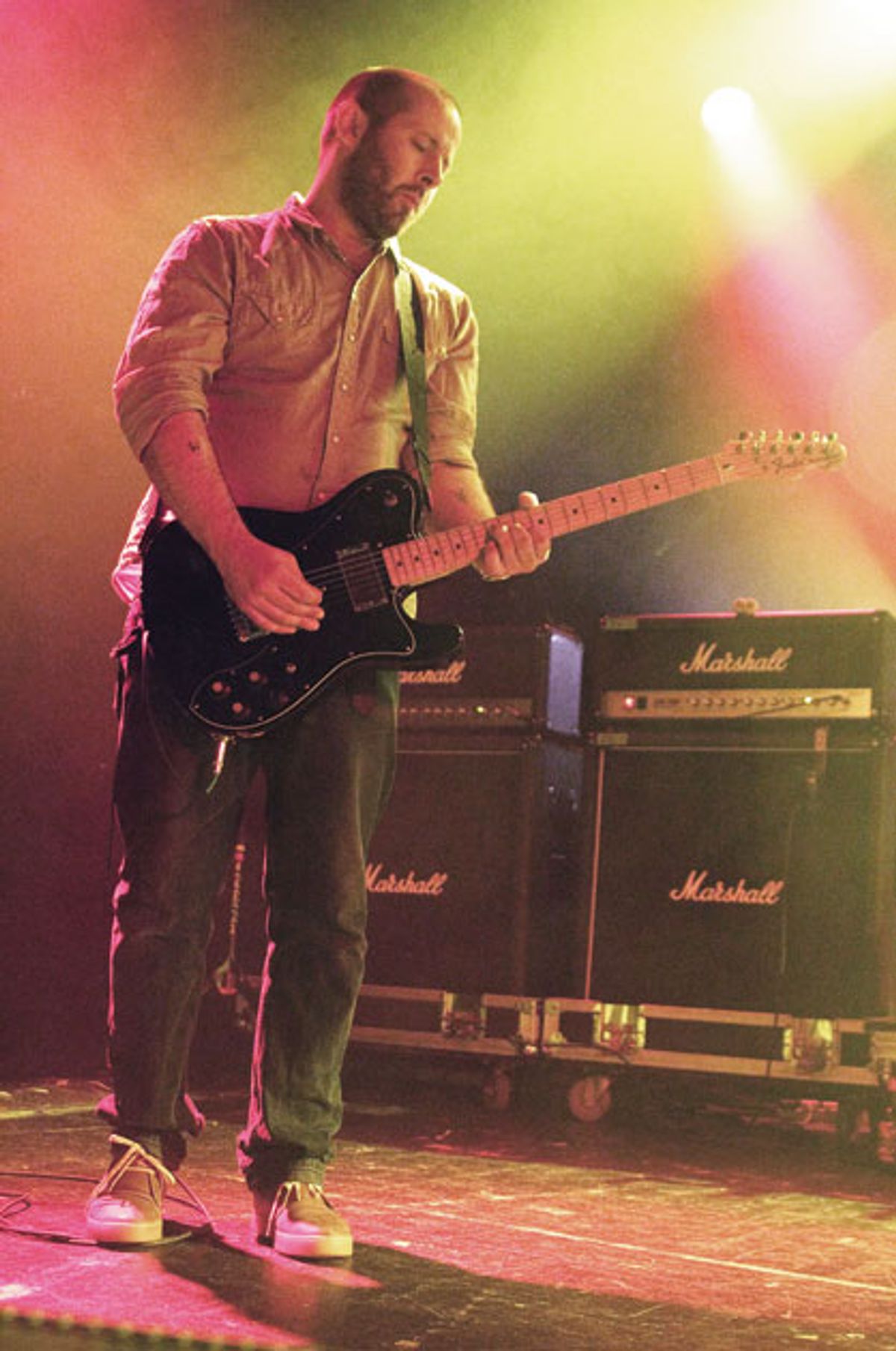

Stuart Braitwaite's Gear

Guitars

1967 Fender Coronado

1980s Fender Telecaster with added Seymour Duncan mini-humbucker and kill switch

Amps

Silverface Fender Super Reverb and Twin Reverb

Orange Crush CR120H

Effects

Boss DD-20 Giga Delay

Boss RC-20XL Loop Station

Boss RV-5 Reverb

Boss SL-20 Slicer

Boss RE-20 Space Echo

Boss TR-2 Tremolo

Danelectro Fab Tone

Electro-Harmonix Big Muff

Electro-Harmonix V256 Vocoder

Pro Co Rat2

MXR Carbon Copy

MXR Micro Flanger

Sonuus Wahoo

Strings and Picks

Dunlop Nickel Wound (10 Medium)

Dunlop Tortex picks (.60 mm)

Talk about the axes and amps you used on the record.

SB: I mostly used a ’67 Coronado, a great and underrated Fender thinline—that and my main Telecaster. I’m not entirely sure what year it is—it was made sometime in the early ’80s. It has a Seymour Duncan mini-humbucker added in the middle, and an on-off switch that I sometimes use to make a sort of harsh, stuttering sound. I plugged into a bunch of amps including some nice Fender silverfaces like the Super and Twin Reverbs, as well as my Orange.

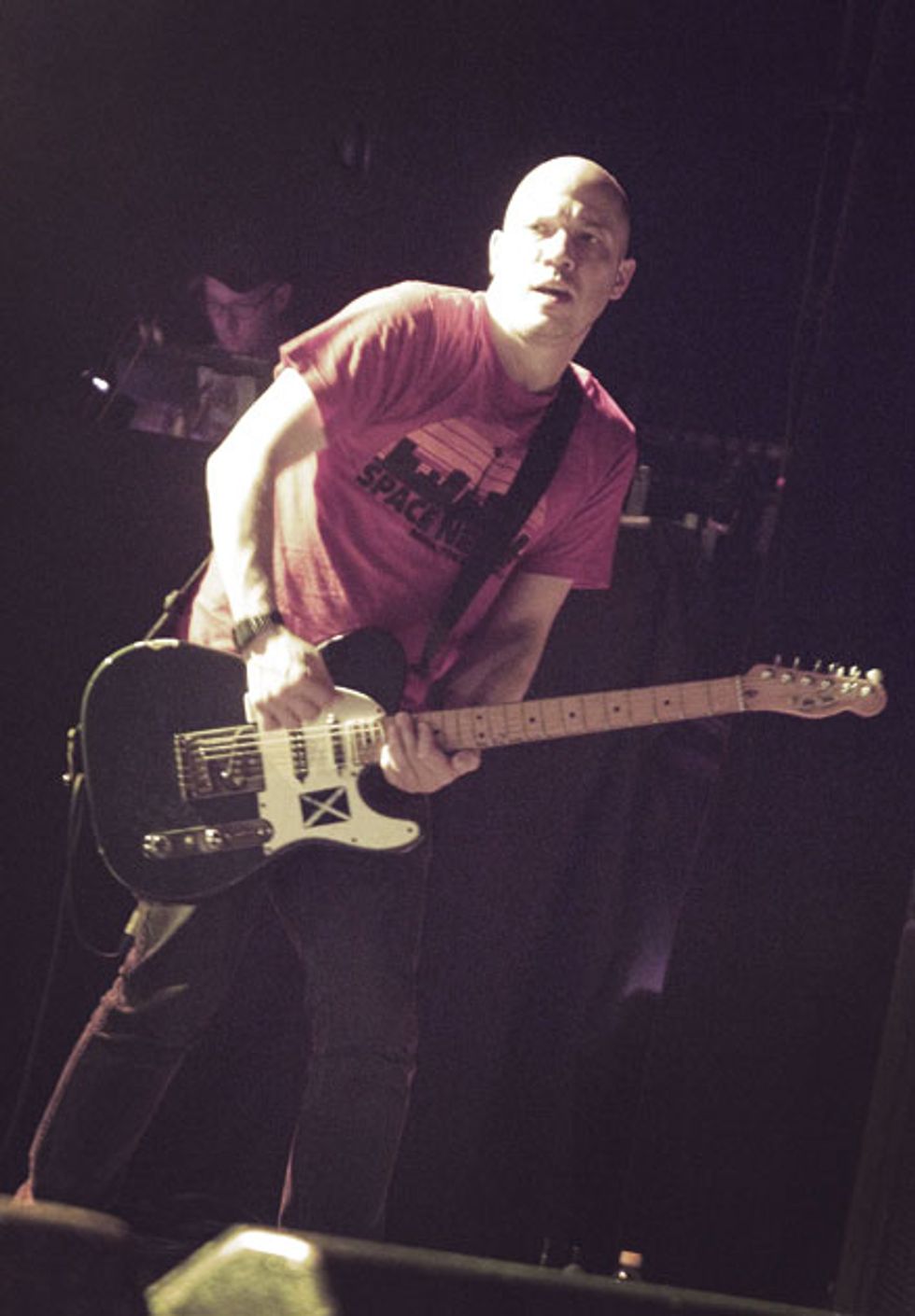

JC: I mostly played a mid-’90s Telecaster Custom, a 1985 Les Paul, and a 1965 Fender XII, plugged into the Marshall Super Bass I’ve had since I was a teenager, as well as a Joe Satriani signature model.

What about the effects?

SB: In the studio we had so many different pedals—quite a lot of Boss, Electro-Harmonix, and more boutique things for distortions and for delays—that it’s hard to remember what I used. One thing that sticks out, though, is a really cool pedal called the [Sonuus] Wahoo, an analog filter that I used for a lot of the sweepy sounds.

JC: I also used mostly distortion and delay, through various Boss, Electro-Harmonix, MXR, and boutique pedals.

Gear

Guitars

Mid-’90s Fender Telecaster Custom and Custom Teles with EMG pickups

1960s Fender Jaguar

1985 Gibson Les Paul

1965 Fender XII

Amps

1970s Marshall Super Bass

Marshall Joe Satriani JCM900

Effects

Boss DD-7 Delay

Boss BF-3 Flanger

Boss OS-2 Overdrive

Death By Audio Fuzz Gun

Death By Audio Interstellar Overdrive Deluxe

Dunlop M159 Tremolo

Electro-Harmonix Holy Stain

MXR Carbon Copy Delay

MXR KFK-1 Ten Band Equalizer

MXR Script Phase 90

Way Huge Aqua Puss Delay

Way Huge Fat Sandwich

Way Huge Pork Loin

Way Huge Swollen Pickle

Strings and Picks

Dunlop Nickel Wound (10 Medium)

Dunlop Tortex picks (.88 mm)

There’s a bit of modular synth on the new record. Are there any special considerations you keep in mind when playing alongside electronic instruments?

SB: If there are, I’m not overly conscious of them. In terms of timbre, guitar and synth are quite an easy fit—they tend to complement each other quite well, so I don’t really need to adjust my playing at all.

JC: Just don’t play the wrong notes! An out-of-tune guitar is much more noticeable when heard next to a synth.

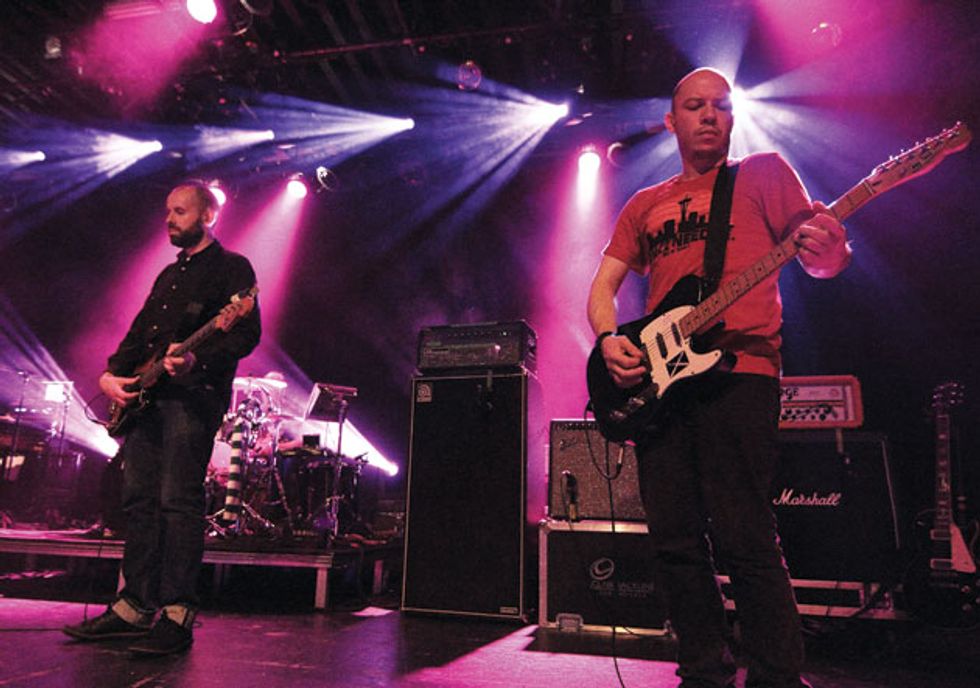

What about tips for sharing space with a second guitarist?

SB: The best thing is to try not to play the same exact part unless you’re really trying to reinforce an idea. It’s best to augment rather than copy, which is something that John and I do naturally.

JC: Yes—just try not to step on the other guy’s toes, and really try to listen to each other.

You’re known to play very loud in concert. What’s the appeal of volume?

SB: No matter the context, a guitar amp turned up loud sounds a lot better than one set at a low volume, even when playing quiet music. It’s important for us that our music be a physical experience, as well as an aural one.

JC: We want the experience of listening to our music to be a powerful sensation that envelops the listener, and this is something that generally can’t be enjoyed at lower volumes. Some great bands—Sonic Youth, My Bloody Valentine, and Spacemen 3—have tended to agree!

There’s awesome howling feedback on “Hexon Bogon” and elsewhere on the record. Do you also play live in the studio, or do you create these sounds through electronic effects?

SB: I kept it simple: I turned up the guitar loud—really loud. With a Marshall and a Rat distortion, it’s hard not to feed back!

JC: Yes, even in the studio we tend to play very loud. We have to be mindful of the placement of our guitars relative to the amps, so that we only get feedback when it’s wanted.

What is the source and meaning of the narration on “Repelish”?

SB: The original recording was a Christian radio show from the early ’80s. Due to licensing obstacles, we weren’t able to use it, so we got a friend to re-record it for the album.

JC: We just thought it was pretty entertaining—it wasn’t an intellectual decision or anything. It was nice to add some levity to the proceedings.

YouTube It

“Mogwai Fear Satan,” from the group’s 1997 debut album, has often been revisited in concert, as seen here.

Though Mogwai was conceived as a guitar-driven band, it’s not unusual for guitars to mingle with keys, as in “I’m Jim Morrison, I’m Dead.”

If you’ve got an hour or so to spare, check out some of Mogwai’s concert-length videos, such as this one.

How have you evolved as a musician since the band started?

SB: I’ve definitely gotten better at what I do. I might have neglected every other aspect of music other than what the band does, but in Mogwai, I think I’ve improved tenfold.

JC: I actually understand more of what people are saying when they talk about music. I am definitely more conversant in theory and harmony than when I started playing in the group, something that happened out of necessity.

What’s kept the band together for so many years?

SB: We’ve always gotten on quite well, and after almost 20 years of playing together, we’re actually still interested in music! Luckily, audiences have also maintained an interest in our music.

JC: And it’s nice to now be playing for people who might not have even been born when the band started.