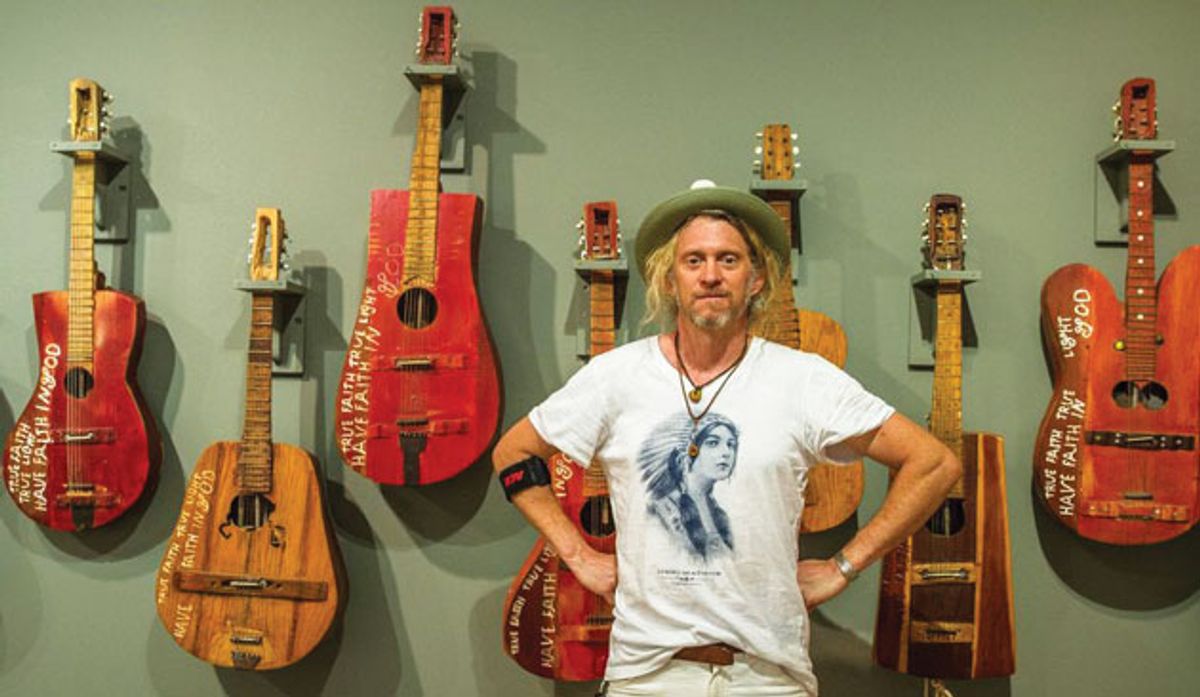

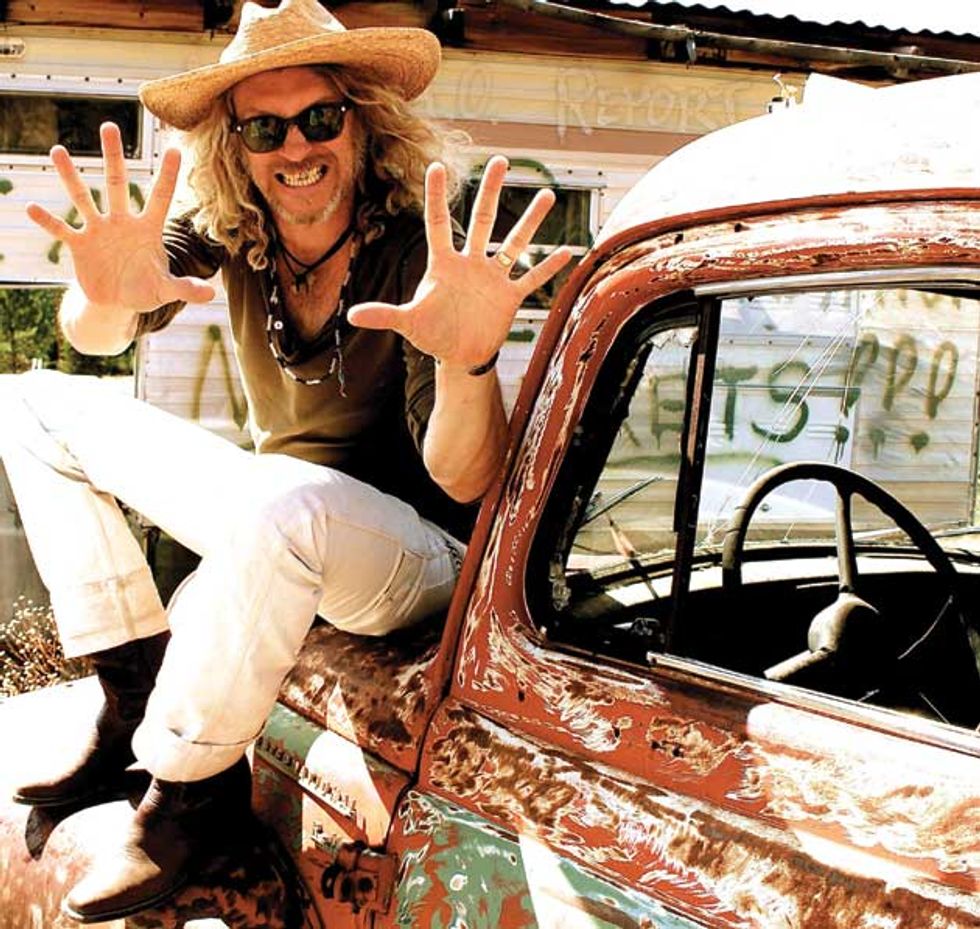

The founding Squirrel Nut Zipper talks about Romantic poetry, losing his ego, and the raw intensity of his latest record with the Tri-State Coalition.

Don’t look for gloss on the latest release from veteran singer-songwriter/guitarist Jimbo Mathus and his band the Tri-State Coalition. Starting with the body-punch impact of the opening title track and carrying on for eleven more songs, Dark Night of the Soul delivers American rock ’n’ roll with a raw intensity rare in an era when every note is tweaked to so-called perfection.

For the Mississippi native—who first came to fame as leader of the swing-revival band Squirrel Nut Zippers—the sound of Dark Night of the Soul mirrors the process of writing and recording. Working with producer Bruce Watson at Dial Back Sound studio in Water Valley, Mississippi, Mathus says he brought to life ideas he may have ignored or set aside in the past. He’s also quick to credit the members of the Coalition.

“There’s no way to cut a record like this one without a good band—it starts with them.” By “them,” he means co-guitarists Matt “Pizzle” Pierce and Eric “Roscoe" Amble, bassist Matt Patton, keyboardist Eric Carlton, and drummer Ryan Rogers. But before they could bring their intensity to the tracks, Mathus had to write—and that’s where our conversation started.

Where do your songs start—do you come up with something on guitar first?

Very rarely do I find anything on the guitar, though it does happen. They just usually hit me like a bolt of lightning. I’ve been writing for so long that I can hear the music in my head. Usually they just come to me in my imagination, and as soon as I get to a guitar or a piano I can bust it out.

The album’s themes are very personal—and powerful. What’s your goal as a lyricist?

I’ve been doing it so long and so habitually that it’s just a part of my thought process. I mean, I’m never not writing a song. I think about a lot of things, I read a lot, and I talk to a lot of people, and certain things just leap out at me as worthy topics. I don’t like to over-say things. I believe in simple phrases that have a lot of different meanings.

Jimbo Mathus' Gear

Guitars

1960 Gibson B-25 acoustic

Guild D-35 12-string acoustic

1972 Gibson Les Paul

Amps

1954 Fender Champ

How do these songs reflect you today, compared to what you would have written 20 years ago?

I’m able to say so much more. There are themes on this record, like this first song, “Dark Night of the Soul,” involving heavy philosophy, history, archaeology. I attempted to write a song when I was 18 about an ancient mystery in Mexico, and failed miserably. Over the years, I’m still fascinated by mysteries and still want to write about them, but I feel like the practice has paid off. I feel satisfied with my direction in writing.

Do you try to leave room for the listener to bring in their own interpretation of the songs?

That’s the way I’ve learned and trained myself to write. Like romantic poetry, for example, where words are packed with meaning and can mean myriad things. I’ve studied with a poetry teacher from University of North Carolina, and he taught me the philosophy of the English language. You say a lot with a few words, and you understate it in order for it to be passed on, open to interpretation. That’s what I like in writing, movies, art—that space where you jump in.

Who are your influences—beyond your guitar heroes?

The 1950s Charlie Parker recordings on Savoy Records are my favorite things to listen to. I get most of my lyric ideas from the Romantic poets. Charlie Patton is one of my main influences. Keith Richards. Captain Beefheart’s Trout Mask Replica. I like folk music, all of that “old, weird America,” as they say. It’s hard to narrow it down. I am a Southerner and an aficionado of the Deep South, so I draw my influences from [William] Faulkner, Charlie Patton, Muddy Waters—these types of things.

How did the actual recording process take shape?

It was quite simple: Every song was demoed once, with me on my own. Songs like “Casey Caught the Cannon Ball,” “Tallahatchie,” “Burn the Ships,” and “Medicine” were done in one day. The demo is what you hear on the record. I’d have an acoustic guitar and a live vocal mic. Bronson Tew would be on drums. Then I’d drop in a bass, or Bronson would drop a bass and I’d slap on some lead guitar. If Eric Carlton happened to be the there, he’d drop a keyboard on. Bruce [Watson, producer] was like, “I refuse to let you touch these—they’re done.” I was like, “Cool—you like ’em, I like ’em.”

The other eight songs were partially finished demos with just guitar and drums and vocal. The band had the demos for two or three months, and we cut all those songs in just two or three days. We cut them live, with live vocals. And “Dark Night of the Soul” was a brand-new thing the band had never heard. You are listening to the first or second take on the record, and Bruce had the balls to make it the first song on the record.

Photo by Elizabeth DeCicco.

How would you describe your role as a guitarist?

I was mostly on my acoustic. I was really just sitting there leading the band and singing. Most of the parts Matt Pierce played were on my demos—I’d drop his little sketch on there. He’s a very talented, hook-writing guitarist, like Roscoe. And sometimes they’d hash their parts out on the studio floor. By the time it got to the recording itself, I played just the campfire chords on the acoustic, because I like to have that acoustic on my rock ’n’ roll. I played the Les Paul that introduces “White Angel” and the lead on “Windows.” Matt plays the solo on the end. I do my work on the demo side, and on the record I’m worrying about my singing.

You can’t cut eight songs in two days without a great band. The casualness and intensity. I struggled to find the people I really wanted. Roscoe has been with me for about three years now. Matt is my brother-in-law, and he’s been with me about eight years now.

Is it hard to let go and let the other guitarists come up with their parts?

Man, it’s been a goal of mine since a very early age to remove the ego from music. It’s something I was able to do with the Squirrel Nut Zippers. That was a seven-piece band that had to be arranged so there was room for everybody to be heard. It reflects back to my beginnings in music—the big family gatherings with banjos, guitars, fiddles, etc. It’s an egoless process: It’s not my thing or your thing—it’s our thing! I was raised on the social aspect of music, and I’ve carried that idea ever since then. I can’t have it any other way, and it shows in the music. I’d rather quit than play with ego.

How locked in were the arrangements?

In this ensemble there’s really no room to improvise once the song is laid out. It’s a five-piece band, and everybody’s being careful to not clutter each other up. There’s not a lot of room to lose yourself in that spontaneity—but you lose yourself in the song.

YouTube It

Watch Jimbo Mathus and the Tri-State Coalition in action at Ground Zero in Clarksdale, Mississippi.

Some players who also sing say they feel more connected when they sing and play at the same time, as opposed to recording an isolated vocal.

I totally agree with that. If you listen to B.B. King or Little Milton—or any of the guitarists who play and sing and incorporate the two together—that’s where you’re into a really heavy thing. Your whole body, mind, and soul are engaged.

The album is already getting some great response. What’s next?

We’ve got a huge tour booked. My hopes are that this is our year. I don’t think we can do better for rock ’n’ roll than we did with Dark Night.