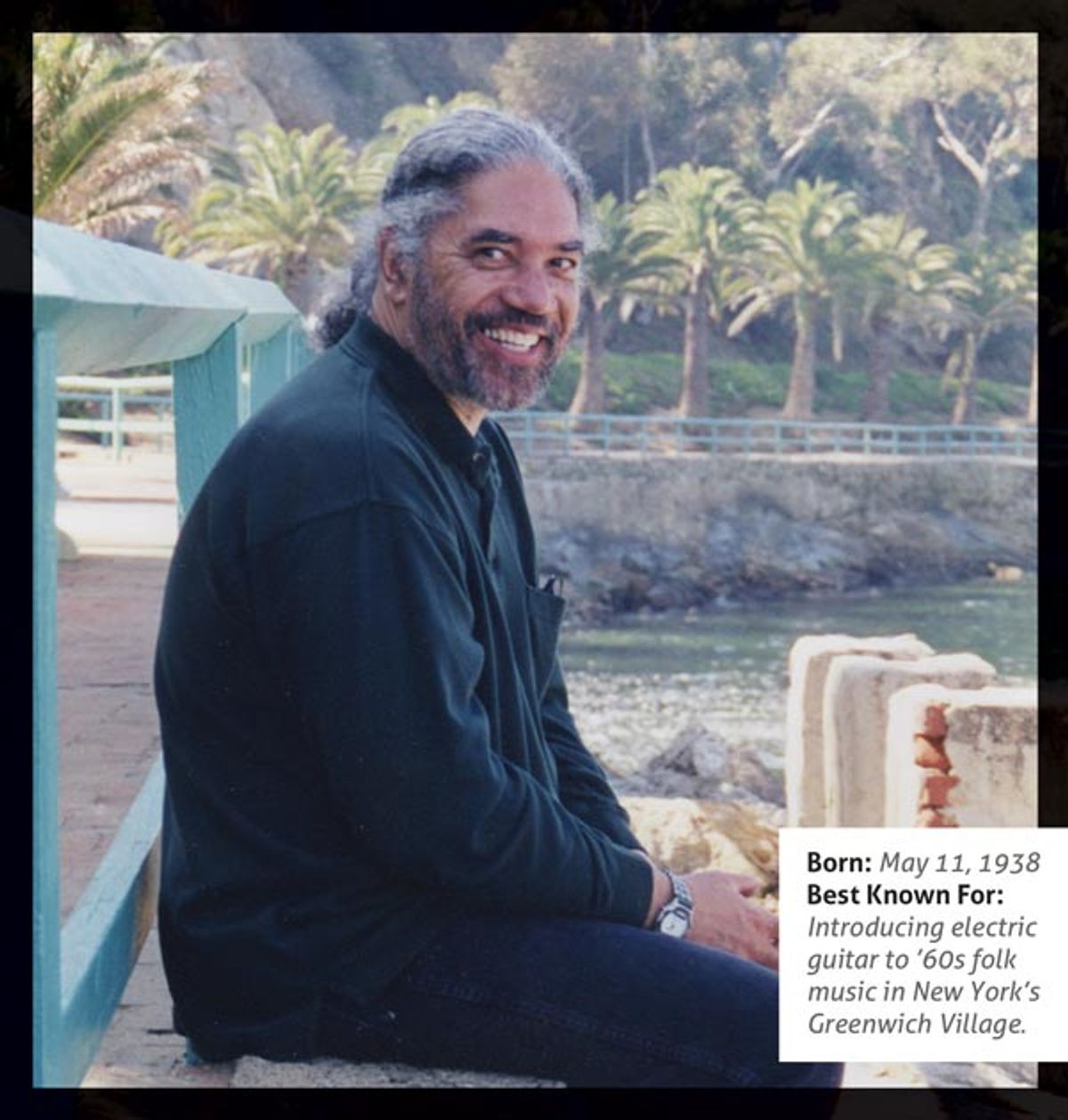

You may not know his name, but “Mr. Tambourine Man” helped pioneer ’60s folk-rock with his amplified Martin flattop.

You may well be asking, “Bruce who?” That’s why Bruce Langhorne qualifies for the “forgotten” part of Forgotten Heroes. But talk to Bill Frisell, Steve Earle, or Jonathan Demme—or just read on—to understand why the guy is a guitar hero. His best-known claim to fame is his fretwork on a couple of early Bob Dylan records, but Langhorne’s importance goes beyond that. His sensitive, call-and-response accompaniment on seminal records by Joan Baez, Odetta, and Richard and Mimi Fariña contributed heavily to the lexicon of licks used by sidemen ever since. Moreover, his decision to place a pickup on his Martin acoustic and plug in to a Fender Twin helped herald the transition from folk to folk-rock and change the face of popular music forever.

Early Days

Bruce Langhorne was born in Tallahassee, Florida, in 1938. His father was head of English at the Florida Agriculture and Mechanical College for Negroes. His parents split when he was four, and his mother raised him in Spanish Harlem, where she was in charge of the Harlem library system. She played piano until a young Bruce took it apart to see how it worked.

with Bob Dylan

Both parents were light-skinned African-Americans, and young Langhorne got into fights for looking too white, too black, or too Puerto Rican. He attended the prestigious Horace Mann Prep School in New York until he was expelled. He has claimed that he was in gangs and stabbed someone as a teenager, requiring him to escape to Mexico for two years.

At 12 he was a budding violin prodigy, but a concert hall career was not to be. When Langhorne lit the fuse on a homemade rocket, he hadn’t calculated how fast the powdered magnesium propellant would burn, and the rocket exploded. His mother raced to Bruce’s room to discover that her son had blown off a significant portion of his right hand. Apparently his first words were, “Well, at least I won’t have to play that stupid violin any more.”

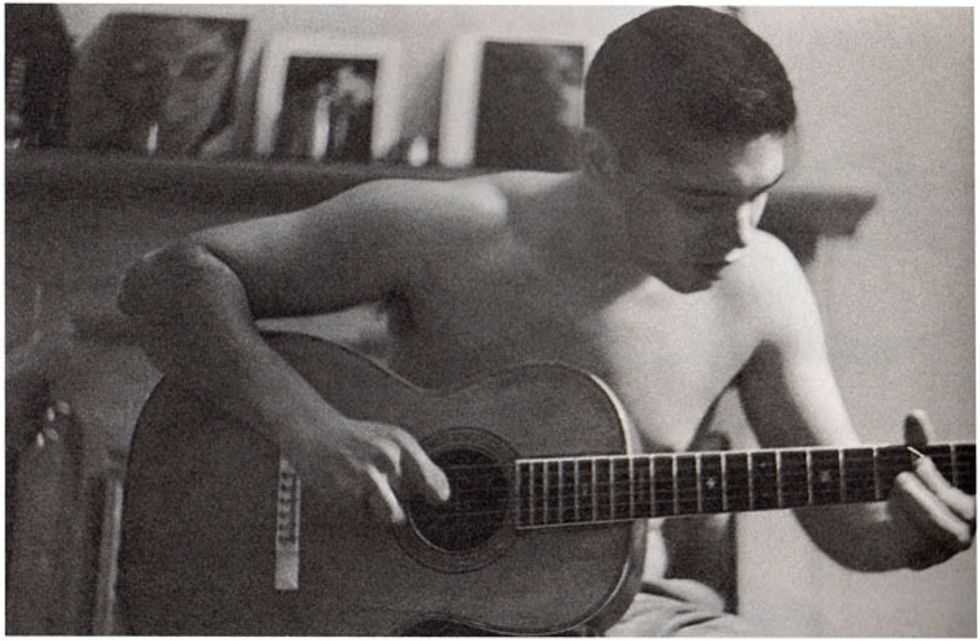

Langhorne didn’t start playing guitar until he was 17, when he performed alongside a caricaturist in Provincetown, Massachusetts, who would sketch those who stopped to listen. Having lost most of his right hand’s thumb, index, and middle fingers, he basically picked the strings with two fingers and the nub of a third. “I had to rely on communication and empathy,” he said. “Which is why I really liked working with Bob Dylan.”

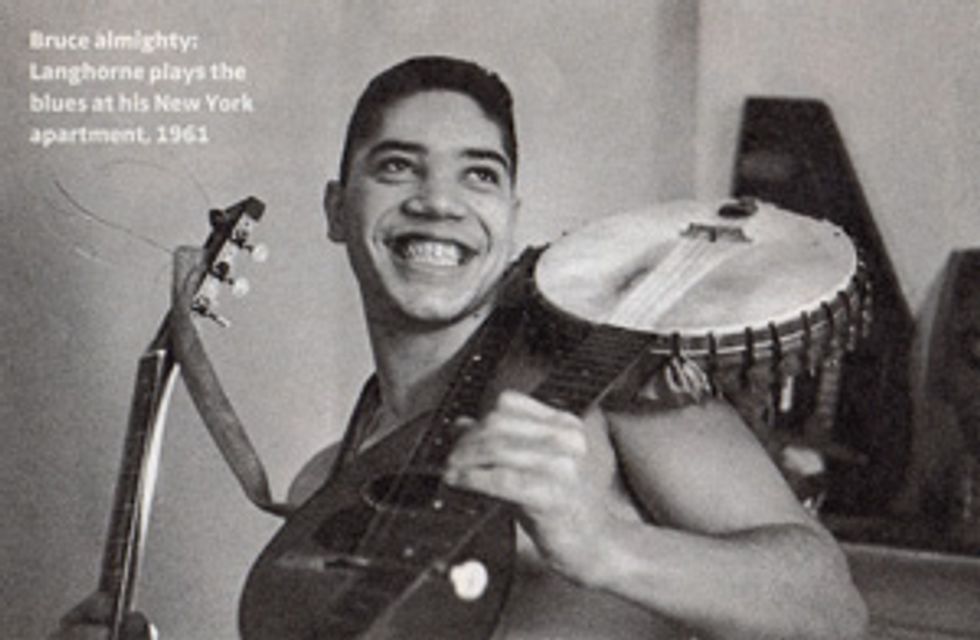

According to Bob Dylan, Langhorne and his oversized tambourine inspired the name “Mr. Tambourine Man.”

The Seeds of Folk-Rock

It was in the burgeoning Greenwich Village folk scene that he eventually met the songwriting legend. Langhorne began as an accompanist to folksinger Brother John Sellers, then working as an emcee at the original Gerde’s Folk City on Mercer Street. That gig allowed Langhorne to sit in with numerous Village musicians and eventually led to work as a live accompanist and in the studio.

An early recording session was for Carolyn Hester’s first Columbia album in 1961. According to David Hajdu’s book Positively 4th Street: The Lives and Times of Joan Baez, Bob Dylan, Mimi Baez Fariña, and Richard Fariña, Hester and her producer decided to add a second guitarist and chose Langhorne, who had become a “one-man house band” at Folk City. That session also saw a pre-fame Bob Dylan on harmonica. Other sessions included dates for the Clancy Brothers and Chad Mitchell Trio.

Langhorne’s first impression of Dylan was less than stellar. “I thought he was a terrible singer and a complete fake, and I thought he didn’t play harmonica that well,” he says in Hajdu’s book. “I didn’t really start to appreciate Bobby as something unique until he started writing.”

Dylan’s masterful writing was in full force on 1963’s The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, but the only tune featuring Langhorne’s playing is a cover of the traditional “Corrina, Corrina.” Around the same time he contributed electric guitar (though mixed so far in the background it sounds acoustic) to an obscure Dylan single, “Mixed Up Confusion,” which was barely distributed.

The Guitar

“I had this old Martin that I played on everybody's sessions, because it was just such a wonderful-sounding instrument” —Bruce Langhorne.

That old Martin and its original case are currently in the possession of Maple Byrne, guitar collector, historian, and tech to Emmylou Harris and Buddy Miller, among others. Byrne reverently calls himself the instrument’s custodian, rather than its owner. He bought it through Heritage Auctions after it had been on display at Paul Allen’s EMP museum.

“It is a 1920 Martin 1-21,” says Byrne. “Size 1 would have been the standard guitar size in the 1890s. A 21 has slightly less ornamentation than a 28. The “2” in 21 means rosewood back and sides—very rare for that year. This size was prevalent in the 1890s, but you couldn’t put steel strings on those. They are X-braced after about 1908, but even then were not braced for steel strings—people used silk and steel strings. By 1920 they didn’t make many guitars this small, but the ones they did build had modern bracing.”

The modern bracing holds firm under light-gauge flatwound strings like those Langhorne used throughout his career. The flatwounds may have been easier to manipulate with the nubs of his lost fingers, and definitely contributed to the dark tones that make him distinguishable on record, even on those containing multiple guitarists.

Langhorne probably bought the guitar at the Music Inn on West 4th Street in Greenwich Village. This is confirmed by Jeff Slatnick, who has worked there since the ’60s. “Bruce used to come in a lot,” he recalls. “He most likely got the guitar here, since we were the only guitar store in the Village at the time.”

“For a collector—I mean serious guitar nerds like Maple and myself—this piece has it all,” says Steve Earle, “First, it's a size 1 Martin: the model from which all American flattop guitars are descended. And this particular one belonged to arguably the best guitarist living and working in Greenwich Village at the height of the folk boom.”

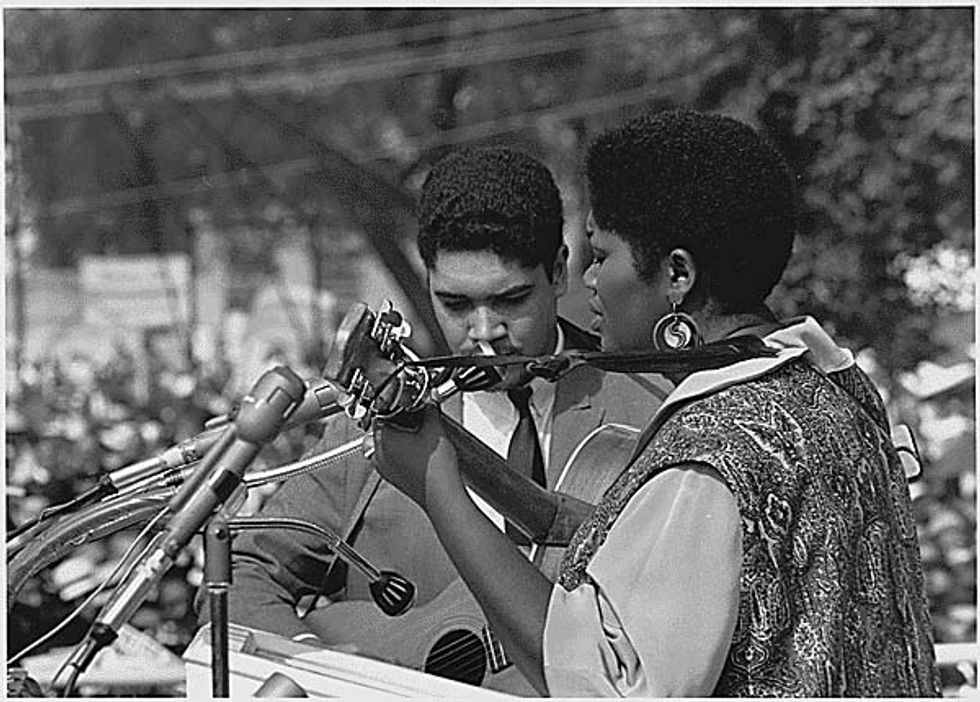

Langhorne first recorded with Bob Dylan while accompanying singer Carolyn Hester in 1961.

(L-R: Langhorne, Hester, Dylan, and bassist Bill Lee.)

The year 1963 found America in turmoil: John Kennedy would be assassinated in November, only months after Martin Luther King gave his “I Have a Dream” speech at a 300,000-person March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. Bruce Langhorne was also at that podium, accompanying African-American folksinger Odetta.

Langhorne’s playing skills were very much in demand by 1965. He appeared on records by Odetta and Joan Baez, and commenced a working relationship with Baez’s sister Mimi and her husband Richard Fariña. Mimi Fariña played guitar, while Richard displayed dulcimer in a unique, rhythmic strumming style. Langhorne added acoustic and electric guitar, as well as percussion. He developed a close relationship with Richard, as Fariña’s Cuban heritage also made him one of the few non-Caucasians in the largely white folk scene. And they were fellow hell-raisers, shooting at mailboxes while driving upstate in Langhorne’s car.

Langhorne had great respect for Mimi’s guitar playing. When he found two stellar, 12-fret, V-neck Martins in his guitar-buying travels, he bought one for Mimi.

Though Dylan’s Bringing It All Back Home is rightly credited with heralding the beginning of the folk-rock era, Richard and Mimi Fariña were moving in that direction at the same time, and Bruce Langhorne helped create the new sound for both parties. Langhorne’s stabbing electric blues licks on “Reno Nevada,” from the Fariña’s Celebrations for a Grey Day record lift it well out of the folk tradition. In fact, label head Seymour Solomon deemed the solo such “abrasive noise” that he almost refused to release it. It sounds tame today, but in the context of the day it might as well have been Captain Beefheart.

Langhorne was one of several guitarists on Bringing It All Back Home. Others included session guitarist Al Gorgoni and Kenny Rankin, who would go on to be a successful artist in his own right. Much of the record was cut in one day. “There were a whole bunch of studio cats, and we were unrehearsed,” Langhorne related in Hajdu’s book. “No lead sheets. Everyone would just start playin’. I don’t even remember Bob runnin’ though the songs once.”

In a 2007 interview he recalled: “The connection I had with Bobby was telepathic, and when I use that word, I mean it. Between the two of us, that level of communication was always very strong. I played on every song on Bringing It All Back Home. Some of those numbers were barely rehearsed. Some were done in one or two takes.”

YouTube It

Langhorne’s tremolo guitar and distinctive pull-off parts add depth and mystery to Richard and Mimi Fariña’s folk-based sound.

One song on the record was “Mr. Tambourine Man,” later a pop hit for the Byrds. On the record’s track notes Dylan reveals the origin of the tune. “‘Mr. Tambourine Man,’ I think, was inspired by Bruce Langhorne,” he says. “Bruce was playing guitar with me on a bunch of the early records. On one session, [producer] Tom Wilson had asked him to play tambourine. And he had this gigantic tambourine. It was like, really big. It was as big as a wagon-wheel. He was playing, and this vision of him playing this tambourine just stuck in my mind. He was one of those characters ... he was like that. I don’t know if I’ve ever told him that.”

Dylan went on to employ Michael Bloomfield and Robbie Robertson as guitarists, and Langhorne would not work with him again until the movie soundtrack for Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid in 1973.

By the time he was interviewed for the Martin Scorsese film No Direction Home: Bob Dylan, Langhorne had revised his initial impression of Dylan: “I remember he was different. He was doing Woody Guthrie songs. He had on a little hat, he had a [harmonica] brace. There’s a quality of determination and of will that some people have, that when they are doing something they are really doing it and you know that you have to pay attention to them.”

Studio Success

The remainder of the ’60s and early ’70s would see Langhorne playing on and producing records for a Who’s Who of the burgeoning folk-rock world—what we would now call Americana. The list includes Buffy Sainte-Marie, Eric Andersen, Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, John Sebastian, Richie Havens, and Tom Rush. As former folkies scrambled to embrace the sound Dylan and the Fariñas had pioneered, Langhorne became the go-to guy. Artists outside the folk world, such as Hugh Masekela and Hoyt Axton, also recognized his talent.

In the early ’60s Langhorne married his first wife, Georgia, an African-American ballet dancer, but the marriage lasted only 18 months. By 1969, he was living with his long-term girlfriend, Natalie Mucyn, when he was approached by actor/director Peter Fonda. Fresh off his success in Easy Rider, the actor was allowed an unusual degree of editorial control for his 1971 directorial debut, The Hired Hand. He commissioned Langhorne to compose a soundtrack based on his facility with traditional American instruments like guitar and fiddle. Langhorne worked with film editor Frank Mazzola, who has affirmed the music’s resemblance to later film scores by Ry Cooder. “The work Bruce produced was years ahead of its time and yet remains unique,” said Mazzola. In a 2007 interview, Fonda recalled the studio’s initial opposition to his choice of composer. “I reminded them that, in the world of music, the word ‘virtuoso’ still means something,” he said.

Langhorne Licks

Lacking a full compliment of fingers, Bruce Langhorne had to develop his own technique. His early influences were R&B, and the first record that caught his attention was Ruth Brown’s “Mama, He Treats Your Daughter Mean.” He was also into Wilson Pickett and the great jump-blues bandleader Louis Jordan.

Langhorne also found inspiration in classical music, particularly in the way composers create polyphony by weaving together individual lines. In the studio he’d listen to the song and the other players, and then figure out a part with three voices—a number he could control with his injured right hand. In an interview with Richie Unterberger he explained, “I needed someone who had a thread going to really do my job, because then they could generate a couple of lines of polyphony or a rhythmic structure, and I could enhance that. I got to be a very good accompanist for that reason. I was really forced to listen, and that’s essential for an accompanist.”

On The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan Langhorne added an additional acoustic guitar part to the traditional tune “Corrina, Corrina.” His sliding sixths helped establish Langhorne as a distinctive guitar voice in the folk era. They appear again on “She Belongs to Me.” The same album displayed Langhorne’s ability to weave a countermelody around a vocal on “Mr. Tambourine Man,” the tune he inspired, and in a lower register on “It’s All Over Now Baby Blue.”

His out-front acoustic work on Odetta Sings Dylan, also recorded in 1965, offers a deeper look at his style. Langhorne’s insistent hammering-on throughout “Master of War” is mixed way up, making him an equal partner in interpreting this dark masterpiece. On “The Times They Are A-Changin’” he demonstrates his knack for weaving countermelodies to the vocal line, along with surprising note choices and two-note pedal tones that build almost unbearable tension. Though soulfully jazzy, Odetta’s version of “Mr. Tambourine Man” would have lived in the parlor rather than the alley without Langhorne’s hook of alternating the 5 and b7 over each chord.

Langhorne has described how he came upon the unique electric sound he used to color those recordings. On sessions where electric guitar was needed, he would clamp a magnetic soundhole pickup (probably a DeArmond) to his old Martin. Langhorne was friends with Sandy Bull, a brilliant multi-instrumentalist who made visionary instrumental records using delay, overdubbing, and non-Western musical elements. Langhorne would borrow Bull’s brown Fender Twin Reverb for sessions. Heavily influenced by Staples Singers patriarch and guitarist Roebuck “Pops” Staples, he would fiddle with the amp’s tremolo until he found a speed compatible with the tune’s tempo and feel.

Langhorne accompanied singer Odetta at Martin Luther King’s March on Washington on August 28th, 1963.

Another soundtrack for a little-known Fonda movie, Idaho Transfer, followed, but it was acclaim for The Hired Hand that brought Jonathan Demme calling. It was the beginning of a working relationship that would include such Demme movies as Fighting Mad and Melvin and Howard.

In 1976 Langhorne did the Stay Hungry soundtrack with fiddle player Byron Berline for director Bob Rafelson. Starting in 1977 he partnered with Morgan Cavett in a recording studio called Blue Dolphin. Cavett had worked with Steppenwolf, produced records, and discovered The Captain & Tennille. It was in this studio that some of Langhorne’s soundtracks were realized.

Moving On

A third collaboration with Demme was planned, but never realized. “Bruce had done a magnificent score for a film of mine called Swing Shift,” Demme is quoted as saying. “Langhorne wrote original live music in the style of 1940s big bands and 1940s jazz, and fused it into the dramatic score that he had written. Had I not been fired, had Swing Shift not been re-edited, had Bruce’s score not been trashed, he would undoubtedly have gotten a fucking Oscar nomination for his extraordinary work on that movie. To experience the horror of seeing work of that quality thrown into the trash by Warner Brothers ... I have always suspected that it was on the heels of this that Bruce chucked it in and moved to Hawaii.”

There were other factors in Langhorne’s relocation. “I was no good at Hollywood studio politics,” he said. “And I didn’t enjoy the parties.” Also, perhaps encouraged by his indulgence in substances freely circulating at the time, the guitarist had become fascinated by the trance effect of prolonged percussion playing. In 1980, Langhorne left Los Angeles for a cane shack in Hawaii and began a career as a macadamia nut farmer. The nut farm proved more work than Langhorne anticipated, and he returned to Los Angeles in 1985, settling into a house in Venice Beach and playing with a wide range of musicians, including the late Nigerian percussion master Babatunde Olatunji.

In 1992 Langhorne was diagnosed with Type 2 diabetes. This led to a new career as developer and purveyor of Brother Bru-Bru’s Hot Sauce. At 8,400 Scoville heat units, Brother Bru-Bru’s is a little more than twice the strength of Tabasco. Made primarily from expensive habanero peppers (most producers use the cheaper jalapeños), it is manufactured in the U.S. The sauce is largely sold in small health stores because, inspired by Langhorne’s illness, Bru-Bru’s has no salt, sugar, gluten, artificial coloring, or preservatives.

The binding on Langhorne’s 1920 Martin 1-21 is actually light wood, as on many of today’s guitars.

Langhorne continued to do soundtrack work into the ’90s, largely employing keyboards. (“Just another tool to make music,” he noted.) In 2003 he formed the Venice Beach Marching Society, a tribute to the music of New Orleans that parades down the Venice boardwalk every Saturday with a cart of amplifiers and a drum.

As his illnesses progressed (including a 2006 stroke), Langhorne gave up guitar altogether. “I figured I had done what I was supposed to do on guitar,” he said. “If I never did anything else on the planet, the things I did were significant and timeless in a way, so I didn’t have to do anything else.” Still, 2011 saw the release of his one official solo record, Mr. Tambourine Man, a Caribbean-influenced affair featuring mostly keyboards and percussion.

As they say: “Those who know, know.” But if the vast majority remains unaware of this extraordinary talent, perhaps it’s because he has always considered himself creatively ambitious, rather than career ambitious. Jonathan Demme offers an explanation: “He never had to look for work. People came to him. He is a tremendously unambitious guy. That’s how he can be a genius and not better known.”

Langhorne has his own explanation: “I have always believed that fame is a curse,” he says. “I don’t envy one of the famous people that I have ever met.”

Langhorne Testimonials

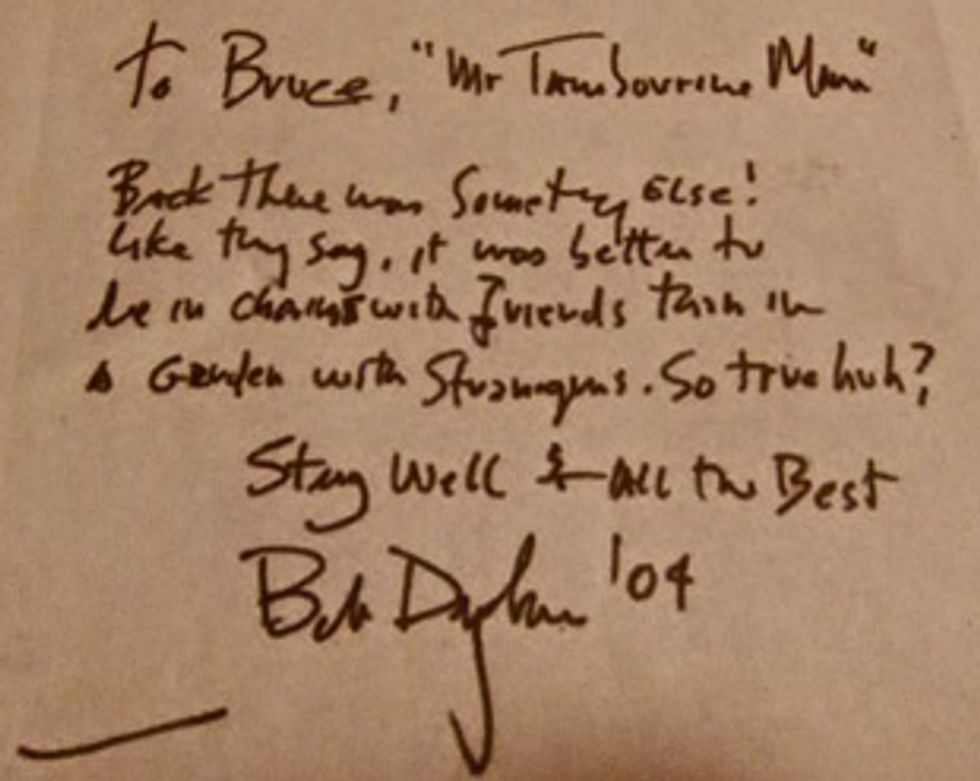

“If you had Bruce playing with you,” Dylan wrote in his 2004 autobiography Chronicles, “that’s all you would need to do just about anything.”

Folksinger Tom Rush once came to this author’s college and played in the dorm lobby on a small stage. Sitting behind him was a swarthy man with a Zapata mustache playing along on a Martin acoustic with a DeArmond magnetic soundhole pickup that was plugged into a Fender Twin Reverb. I was a big Tom Rush fan, but by the end of the show it was Bruce Langhorne I wanted to be. He made me want to play those cool fills around the vocals that lifted the music to a plane unachievable by a self-accompanied solo artist. Sometimes dreams come true: In the ’80s I was on tour, playing the riffs around the vocals for Eric Andersen—an artist Langhorne had accompanied on record in 1970. “I remember recording with Bruce once,” recalls Andersen. “He did an extraordinary guitar solo and some tambourine parts for my song ‘Foolish Like the Flowers.’”

And, of course, Joan Baez, who was in the thick of the action at the time, also recalls Langhorne. “Bruce worked with me on one of my favorite albums, Farewell, Angelina,” says the ’60s folk goddess. “My fondness for that album is largely due to Bruce’s distinctive guitar playing. He was also a pal, a laughing mate, and a general all-around gem.”

I’m not the only guitarist whose concept of the instrument was affected by Langhorne. Bill Frisell recalls hearing the session ace around the time he first took up guitar. “I didn’t realize how big an influence he was until many years later,” says Frisell. “It was almost subliminal, but that is too soft a word. He had this gigantic effect on the way I play music—it was a revelation. I used to listen to early Bob Dylan records he was on when I was a kid, lying on the floor with the speakers next to my head, playing them over and over. I just heard him as part of the total sound. Years later I realized his playing was this line between accompanying and having a conversation, being spontaneous and completely integrated into the music from the inside out, playing a part but not a part, unpredictable. When I heard all that later, I realized that was the way I have been trying to play my whole life. It doesn’t matter what kind of music I am playing, whether a jazz instrumental thing or with a singer, it is more the attitude he had. There are people who can teach you so much in a split second. They open the door to let you know it is okay to go on with the way you have been thinking. I realized he was on other records I used to listen to, part of the fabric of the sound that was around when I first got interested in playing.”

In a 2007 interview director Jonathan Demme stated: “Just occasionally you come across these geniuses. Bruce Langhorne was one. These people all tend to work in the same way: They respond instinctively to the visual image. I still remember the insane thrill of being with Bruce in his apartment, with his guitar and other instruments, and looking at scenes from Melvin and Howard. He was playing things and I was just saying, ‘Oh my God, that’s amazing.’ Bruce Langhorne has done some of the most beautiful scoring that I have ever been involved with, or ever known.” —Michael Ross

To hear Bruce Langhorne’s never-released song, “Old Dog,” visit brucelanghorne.com/old-dog/.