The Colorado sextet perfect their multi-genre approach with a new album produced by a Talking Head.

There are certain geographic regions that just drip with an undeniable musical identity. The sound of James Jamerson’s groove on the Detroit Motown sides, or the tight-but-loose country-rock stylings that blossomed out of Alabama’s Muscle Shoals have defined those regions as much as anything else. For nearly 20 years, The String Cheese Incident has created an incredibly intense, but powerfully distinctive sound surrounded by the picturesque Rocky Mountains. The Boulder-based collective chews up and spits out everything from EDM and dubstep to bluegrass and Americana with staggering authenticity.

That natural process of collecting, absorbing, and interpreting various influences has turned what began as a forward-thinking progressive acoustic quartet into a muscular and dynamic sextet that could easily go from Coltrane’s “Impressions” to Nelly’s “Hot In Herre” without blinking an eye. “If you listened to a tape of what we sounded like then and what we sound like now, there would be some head-scratching,” says frontman Bill Nershi.

they see us live. —Michael Kang

The wonderment would be a result of Song in My Head, the group’s first studio album in nearly a decade. Even after a cursory listen, you can tell that the Cheese has moved well past the Grisman Quintet sound of their early years. On “Rosie,” the band proves they can flip on the electronica switch and create a beat-filled dance jam that isn’t any less danceable just because it’s played by a group of self-described ski bums from the mountains. Other tracks touch on everything from Fela-inspired Afropop (“Betray the Dark”) to raise-the-roof gospel (“So Far From Home”).

Admittedly, studio albums aren’t the lifeblood of most bands in the jam scene. It’s all about the show, or what the Cheese calls an “incident”—that wild and unpredictable place where preparation meets exploration and you never quite know what’s going to happen. Psychedelic light shows, themed costume parties, and general musical silliness have served as the cornerstones of many incidents over the years.

We caught up with Nershi and mandolinist Michael Kang as they prepared to hit the summer festival circuit to discuss African rhythms, why they will never be an electronica band, and the good and bad parts about working with a producer.

This is your first studio album in a decade. At what point did you decide as a band that now was the right time to record?

Bill Nershi: I’ve been trying to get the band to do it for probably the last four years. There’s always the question of “Okay, we’ll make a CD and then what good will that be?” For me, it was more like we have this backlog of material and we need to record some of these songs and get them down, and if we don’t go platinum, it’s okay. We still documented where we’re at as a band.

Michael Kang: We took a break in 2006 and got off the road and everyone retreated into their own lives a little bit more without having to be involved in the group dynamic as much. Since we came back, we’ve played a lot fewer gigs. We’ve always recognized that we have a ton of music we haven’t recorded—probably more than what actually ends up on our albums. But, as a live band, we have always found it important to play shows. I think getting back in the studio was important. Originally, we thought we would use the multitracks from live shows as basic tracks for the album and then do overdubs. Once we started sifting through that we realized that we might as well just go for it in the studio—and we were rehearsing in the studio at the time as well. It was pretty painless and everybody had an enjoyable time in the studio, which hasn’t always been the case for us. Sometimes it can be a little like pulling teeth for different members.

When a song changes shape, both on the road and in the studio, do you aim to make a definitive version when you put it on an album?

Kang: I think in the studio you have the opportunity to hone in some of the finer elements, especially vocals and the sonic texture and balance of all the instruments. It’s really difficult, I think, for anyone to mix us live and really nail it since there’s so much stuff going on onstage. Our last sound guy had over 75 inputs. It’s really nice to go to the studio and make it sound exactly what you want it to sound like. That often informs how it comes out in the live show as well. A lot of these songs have been fine-tuned on the road already.

Nershi: Sometimes songs can be ruined by producers who want to record them a certain way that’s different from what the writer, or even the whole band, has been playing or wants to play. You end up in this limbo between the version that some people have in their minds as the way to play it and the recorded version, and you can never settle down and just play the song the way you want to because you’re split on it. I feel like two things happened during this recording process kept that from being the case.

First, we were in the studio already and recorded all these basic tracks without a producer. So we played them the only way we knew how to play them. It was very simple and production didn’t hold us up. That made it easy and very low stress for us. The other thing was that I really felt like Jerry Harrison, as a successful musician in his own right, had a good feel for what we wanted as a band for the album and for the songs. He had a respect for not messing with the tunes for the sake of being the producer. We ended up with versions of these songs that can be a template for us when we play them live. One thing he did that was really helpful on a couple of the tunes was changing the keys so the vocalist was in a better place to be able to give the song a bit more punch. He didn’t just pry into the songs. He had a sense of how to get the best out of each song without having to take it apart.

Speaking of Jerry, how did that connection come together?

Kang: Jerry is a good friend of a songwriting buddy of ours named John Perry Barlow. We were playing at the Greek Theater and John called us up and said he was going to come to the show and bring his friend Jerry. Interestingly enough, we were actually downstairs trying to figure out what we were going to play—without even knowing that he was going to be there—and we decided on the Talking Heads’ “Life During Wartime.” All of a sudden it became apparent that he was going to come down. So he sat in and jammed with us. About 10 years ago, he was on a list of possible producers for a previous album, but it didn’t work out. At that gig we weren’t even really thinking about an album, but we knew he was still producing. When we decided we wanted to bring in a producer who could help us finish this, he was tops on the list and everyone really wanted to work with him. He’s super relaxed about the whole thing, which really helps.

String Cheese operates without a traditional lead guitarist. Michael, you seem to fill that role a bit with your electric mandolin.

Kang: I play some electric guitar on the album, but mostly my Ron Oates electric 5-string mandolin. With an 8-string, there’s a very specific sound. First of all, it isn’t electric, so your limited to the tonality you can get. Plus, it’s a pretty high-pitched instrument. Early on, I decided I wanted to make more electric guitar-like tones, so I got a 5-string mandolin that had a low C. Eventually, I took it to the 5-string octave mandolin tuned to G-D-A-E-B. Which is a third above the lowest note on the guitar. Ever since then, it’s become my go-to instrument. I like the traditional mandolin, but I feel they can be limiting. I just don’t really play that much acoustic in this band, it doesn’t always find a place in our settings.

Bill, tell me about your T-style electric that you occasionally use.

Nershi: My brother Tom built that for me. He built me that Tele and a couple of lap steels I play from time to time. He’s a craftsman of sorts and a musician, so he’s built a few guitars. He doesn’t make a living doing it, just when he has time and is motivated.

The Gear of String Cheese Incident

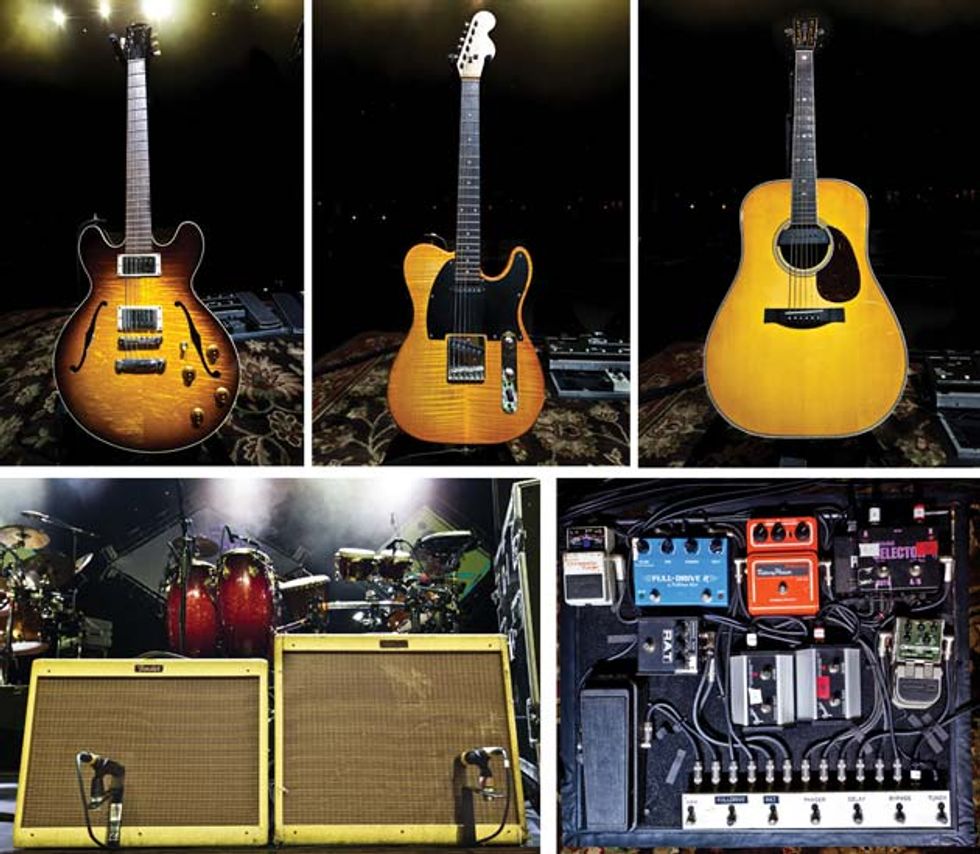

Bill Nershi's Gear

For guitarist, Nershi mainly uses a Collings I-35, a Santa Cruz D-Nershi Signature Model, a ’70s Martin D-28 ("FrankenMartin"), a 1955 Martin D-18, and a Ton Nershi T-Style Guitar. When it comes to amps, Nershi goes with his tried-and-true Fender formula involves a Blues Deluxe and a Blues DeVille. The handful of stomps that he relies on includes: Fulltone OCD, Fulltone Fat-Boost, Ernie Ball Volume Pedal, Boss TU-2 Chromatic Tuner, Fulltone Full-Drive 2, Pro Co RAT, Maxon Rotary Phaser, Dunlop Crybaby Wah, Line 6 Echo Park, TC Electronic G-Force. And for strings, picks, and accessories, he currently jams D'Addario EX115 (.010-.049), Rocktron MIDI Mate, Whirlwind Selector A/B, Sunrise acoustic pickup, K&K Pure Classic acoustic pickup, and Avalon U5.

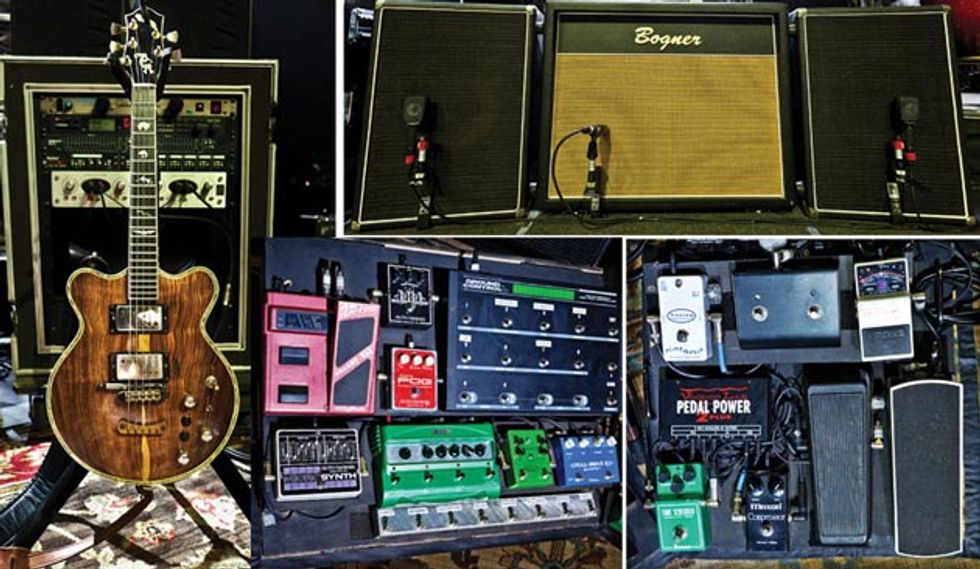

Michael Kang's Gear

What acoustics did you use on the album?

Nershi: I played a bunch. Different guitars will fit sonically better than others. I have an old “FrankenMartin” D-28 that has gone through many transformations. I played that on some tunes. I just got a 1955 Martin D-18 that I played. I also had a Santa Cruz D-Nershi guitar on some stuff.

Tell me more about the “FrankenMartin.”

Nershi: It was a ’70s Martin that wasn’t built well. They had a period of time where they were putting out some odd guitars as far as where the bridge and saddles were placed. I’ve had a new bridge and new saddle installed. I brought it to Costa Rica and the neck bowed and just never went back. My luthier here in Boulder, Jon Eaton, told me it was time to cash it in and get a new guitar. By the time I had stopped crying, he told me he had some necks in the back room. He went back and brought out a selection of Martin necks. We picked one out and he replaced it. It’s had a tough life. I’ve played it hard for many years. [Laughs].

Michael, what’s on your pedalboard?

Kang: It hasn’t changed much over the last seven or eight years. The newest thing is that I go into a device made by Brad Sarno called a Steel Guitar Black Box. It’s basically an impedance matcher. Scott Walker, who is making me some custom mandolins right now, turned me onto it. I go directly into that and then it goes into the pedalboard, which is pretty standard. I have several Keeley pedals, a Maxon compressor, a Keeley-modded Tube Screamer, a Fulltone Full-Drive 2, a Line 6 DL4, and an old DigiTech Whammy Wah. I have a Voodoo Lab Ground Control that controls it all.

Basically, the core of my thing is the Two-Rock Custom Reverb I got about six years ago. I run that as a center channel through a 2x12 Bogner cabinet. I run stereo effects with a TC Electronic G-Force for a lot of tremolo, delay, or special effects-type stuff. Then I just have a couple single 12" cabs that run in stereo through a slave Groove Tubes D75 power amplifier. That’s pretty much the rig I’ve had for the last 10 years.

Bill, describe your acoustic rig.

Nershi: With my acoustic guitar it’s nice to have a stereo sound. I have two pickups in my acoustic. It’s a little complicated. I have the Sunrise magnetic pickup in the soundhole and the K&K pickups underneath the bridge because it’s nice to get a little bit of the wood sound out there. I need the presence of the magnetic pickup with the volume of the music that’s being played. I run through a couple of Avalon DIs with a stereo cable coming out of my guitar and one side runs to each DI. I can adjust the balance there and then I sum them into the back of my TC Electronic G-Force for my stereo effects.

Do you use any amps live?

Nershi: I don’t run through an amp with my acoustic for my in-house sound. I’ve got a couple of AERs that I use just for stage monitors. For my electrics, since the two guitars have such different gain structures, I run them into different amps. The Collings goes into a Fender tweed Blues DeVille, one of the older 2x12 combos. I run my Tele into a smaller, 40-watt Fender Blues Deluxe.

YouTube It

The group revisits the up-tempo bluegrass that fueled their early days with the opener from their latest album.

The band takes ride on one of their funkier tunes, “Miss Brown’s Teahouse,” during the Rothbury Festival—one of only two gigs they played in 2009.

“Let’s Go Outside” has a groove that wouldn’t be out of place at an EDM festival. When did the electronic influence creep in?

Kang: Over the years as we started playing these different festivals, maybe up to 10 years ago, we noticed more of the electronic element entering into the jam scene. On Untying the Knot, a producer who had produced a lot of electronic stuff took one of our fiddle tunes in that direction. It ended up being a trance tune with a four-on-the-floor house beat.

We didn’t really start adding beats in the band until Jason [Hann, percussionist] brought his computer onstage. Jason and Michael [Travis, drummer] have an electronic duo called EOTO where they just play live electronica. They definitely brought that into the group. Before then, there were songs that had that trance-like vibe but didn’t have the electronic beats. We just add it in spots and it’s another point that the kids are able to relate to. You know, we are all in our 40s and 50s and when we go to play a festival, the kids are like 18 or younger. We’ve always prided ourselves, to a certain degree, on taking people on a genre-bending experience when they see us live. Even from the early days, it’s been like that. I think that is just an extension of it. We will never be just an electronic band, that’s not going to be our thing. But it’s nice to have it in the arsenal.

I imagine with so many songwriters and influences in the band, the journey from idea to finished song can take a number of different paths.

Nershi: Yeah, it can be anything from a chord progression or a riff, to a verse and a chorus, to a completed demo that someone will construct in their computer. Depending on the level of completion of the song, it can either be played in its entirety as it’s written or it might be an idea that is brought into a rehearsal session and as a band we will arrange or even write lyrics or parts to it. There’s no rule of thumb. Generally, the band arranges almost all the songs, or they at least add ideas and parts to it. It’s rare that there’s a song written in stone and everybody is handed their part.

Which song on this album changed the most between inception and the final recorded version?

Nershi: “So Far From Home” ended up being a real fast gospel tune. It changed the day we recorded it. We had played it almost like an Allman Brothers-type thing. We realized it would be great if the Allman Brothers were playing it like that, but I said, “Let’s just play it double-time.” It changed on the spot the day it was tracked. It was hard when you have this idea of a song sounding like another band. It can be pretty limiting and frustrating, because of course, that’s a different band that sounds great. But you have to do your own thing and make songs your own—even your originals. When we did that and took it completely out of the vein we were working in, it was exciting and fresh for everybody.

Kang: I think we played it a few times at the slower tempo. Then once you suggested stepping on the pedal we were all like, “Whoa. That was fun.” [Laughs].