Discover the advantages of a straight-pull tuning system.

The early Steinberger prototype. Photo courtesy headlessusa.com

The December 2011 issue of Premier Guitar contained an article by Don Greenwald about a very rare bass. An interesting read for every headless bass enthusiast, “Steinberger Prototype: The Missing Link” describes how Greenwald managed to acquire a very early Steinberger 4-string. The story includes intriguing photos, as well as an interview with Ned Steinberger about this transitional instrument.

Photo 1 shows this prototype Steinberger—the L2 in the middle stages of its development. The bass features a headless design and a one-piece graphite body and neck, but it still sports traditional tuners at the bridge. As we now know, Steinberger ultimately rejected this approach: “I thought the straight-pull tuners were better, so I went in that direction.”

Presumably with no knowledge of this early prototype, some companies did, in fact, install traditional tuners on their headless basses. Two of the best-known examples are the Kramer Duke and Warwick’s Nobby Meidel model.

Yet it’s obvious why Steinberger took the straight-pull route: Standard tuners lack several advantages of “linear tuner” headless construction. For starters, because strings are wound around the tuning pegs, they’re longer than needed and this creates greater tuning instability. Also if you bump into something or when you put the bass in a case, standard tuners can be as easily detuned on a headless instrument as on a classic one. And, of course, regular tuners can’t make use of those double ball-end strings.

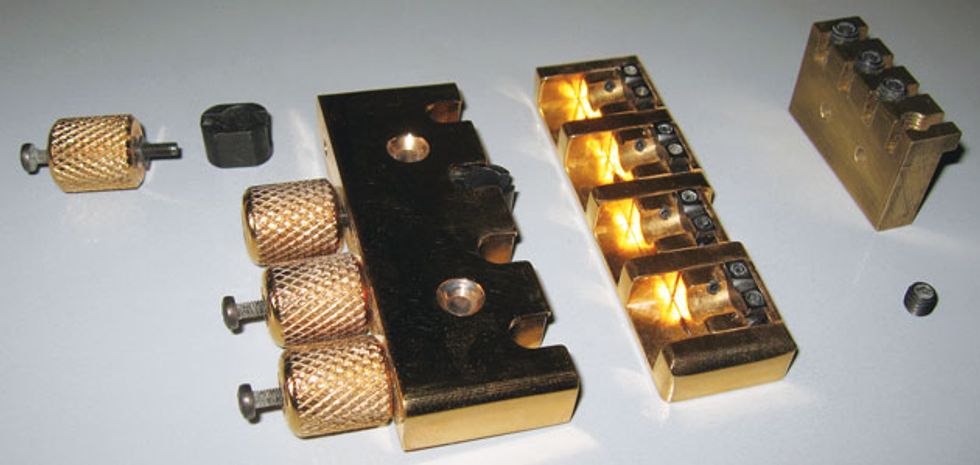

The ABM headless hardware system. Photo courtesy basslab.de

As you can see in Photo 2, only a few hardware parts set a headless bass apart from a classic one. The whole tuner system consists mainly of the tuning-knob screw, a cup to secure the ball end, and the housing—much simpler than any standard tuner housing—to hold these components.

In standard tuners, the gearing has a ratio of approximately 1:12 (sometimes as high as 1:18), and it typically relies on a soft washer acting as a sort of “brake” to prevent it from unwinding. By comparison, the ratio of the linear headless tuner is determined by the threads on the lead screw. (A lead screw transfers rotary motion to linear motion.) With its ratio of 1:40, the final version of the L2 offered very precise tuning.

The simplicity of the headless tuner has inspired many bassists to build their own. Some of these DIY builds look pretty fragile and improvised, but due to the simple mechanism, most of them work flawlessly. Can you imagine the difficulty of making just the gear of a classic tuner on your own?

In addition to the tuning mechanism, the second special part is the headpiece. On the classic L2, this part acted more like a tailpiece, as it only held one of the double ball ends. Given the limited choice of double ball-end strings, later designs had locking screws (as pictured here). This change allowed you to use any brand of bass strings.

A modern extended-range headless bass from Crimson Guitars. Photo courtesy crimsonguitars.com

Due to the simple mechanics, you can find many DIY-headless conversion projects on the web. Some players started these projects because of a broken headstock, while others were simply curious and wanted to explore the concept.

As far as professionally built instruments, these days, the headless design appears mostly on extended-range basses. This is probably because the simplicity and compactness of the system make it a good companion for wide necks and enhanced scale length.

For some players, the small body of the original L2 caused problems because it didn’t provide an armrest like a Fender Jazz bass does. This explains why on today’s headless basses, the L2’s minimalistic body has been replaced by larger, more classic shapes. Looking at this 8-string Crimson extended-range bass (Photo 3), you might notice a physical resemblance to the Klein guitar—an iconic take on ergonomic design that got its inspiration from the first headless basses.