Touring a new tell-all autobiography, Aerosmith’s riffmeister reflects on the highs and lows of a colorful career.

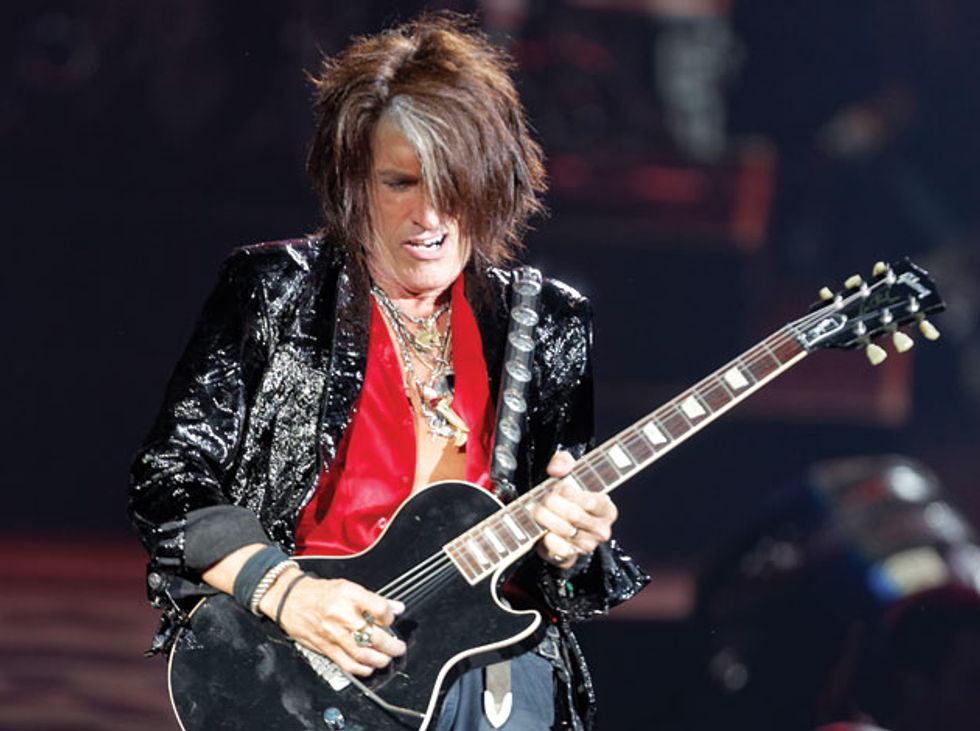

Joe Perry is a guitar-playing kraken—a legendary and impressive creature in his long hair, leather vests, chains, and scarves. When he propels his ripped physique across the stage with a guitar strapped over his left shoulder dispensing delirious bends, wiggy vibrato, and riffs that swagger between major and minor, he’s every bit the classic rock star in the mold of Hendrix, Beck, Page, Townshend, Richards, and other near-mythic giants.

At 64, Perry has survived and thrived as the co-helmsman of Aerosmith for almost all of the band’s 43 years, cowriting the enduring rockers “Same Old Song and Dance,” “Walk This Way,” “Back in the Saddle,” “My Fist Your Face,” “Ragdoll,” “Love in an Elevator,” and even the un-rock ballads “Crazy” and “Amazing.” He has cut 19 albums with Aerosmith, plus another six as a solo artist and leader of the Joe Perry Project. And now he’s sharing his extraordinary experiences in a new autobiography: Rocks: My Life In and Out of Aerosmith, cowritten with David Ritz, who’s undertaken similar projects with Ray Charles, Aretha Franklin, B.B. King, Scott Weiland, and Buddy Guy.

Rocks sketches Perry’s life from his small-town Massachusetts childhood and musical awakening through his sex-and-drugs-cushioned ride to the top, his precipitous drop to the bottom, and the difficult climb back up. Perry’s book is earthier and less guarded than his Aerosmith foil Steven Tyler’s 2012 memoir Does the Noise in My Head Bother You? It delves deeper into the band’s mechanics and complex relationships, including the 12-year period when ex-manager Tim Collins resurrected the group from the rock ’n’ roll boneyard, but then tried to become their puppet master.

Perry recently explained why he chose to collaborate with Ritz: “He’s very heavily into Motown and jazz and blues stuff. I thought that would give him a good perspective on what Aerosmith is. He doesn’t think the Beatles hung the moon. They’re just another group among the generations of musicians who handed their skills down to the next generation. The Dave Clark Five, the Yardbirds, Aerosmith—we’re all just links in a chain. He respects Aerosmith for what we’ve done. He sees our place in the bigger picture, which is an amazing perspective to find in such a skilled writer and a musicologist of the highest order.”

Given Perry’s once-prodigious drug intake, he doesn’t necessarily recall every detail of the past six decades with perfect clarity. But Ritz’s biographer’s technique allowed Perry to flesh out a skeleton of his history.

“He and his assistants put together a chronology of my career based on everything that’s been written about me starting from my high school year book up till now,” the guitarist recounts. “David was also up on all the records. He was quoting lyrics from songs I don’t even remember.”

We spoke to Perry as he was preparing for his initial public reading at a Barnes & Noble in New York City’s Union Square. “When I started thinking about doing the book tour,” he says, “I thought, ‘Wouldn’t it be great to get some of the guys from the Joe Perry Project together to play a short set and sign books?’ But there just isn’t time to do that, so instead I’ll stand up in front of people and tell the story the way it should be told—the way storytellers did it a thousand years ago.” He got a little practice when we asked him about his musical survival strategy, the fundamentals and zeniths of his playing, and, of course, his guitars.

You describe Aerosmith’s story as success, drug abuse, destruction, rebirth, re-destruction, and rebirth again. You’ve said the band became a cult while working with ex-manager Tim Collins. You also detail your repeated frustrations with Steven Tyler, including him not informing the band about auditioning for Led Zeppelin or his deal with American Idol. How do you keep your head in the music during vexing times?

With Tim Collins, you have to consider the time period when that all went down. In the book, it’s a few chapters, but living it was years of ups and downs. The first two or three years we worked with Collins, we were doing things nobody ever did: coming back from the dead, getting healthy. We were middle-aged men with lives that worked for us outside of the band, and yet we were still trying to carry that vibe of five teenagers living in an apartment onto the stage. We got out there and rocked and put all the bullshit aside. Then there were lots of years when things were really screwed up with that guy. We put up with it because we were having success and didn’t want to spoil it.

Being in business together as a band requires talking a lot. We’ve got to talk about tours, recording, production. But we also need to get in that space of being artists putting on a rock ’n’ roll show. We’ve been able to separate those things. There are still times when things go on in the band and I think, “Well, it can’t work anymore.” But there’s something powerful about Aerosmith that keeps us together. Plus, everybody in the band still likes each other. You’ve got to dig deep down sometimes, and there are a lot of death-defying leaps of faith, but that’s one of the reasons I wrote the book. I want people to understand how hard it is. We’re all brothers by choice. You can love your brother, but you don’t always have to like him.

Remaining friends with anybody for over 40 years is an accomplishment.

Thank you. It has been tough. But a lot of people have it tough out there. I’ve got no complaints. But there came a time when I thought, “People have to know what’s going on behind the scenes,” including some of the funny stuff. So it felt like the right time to write the book.

This Gibson Custom one-off boasts a Wilkinson tremolo, a roller bridge, and single Lindy Fralin humbucker.

Photo by Ken Settle.

Is there one gig that you consider the pinnacle Aerosmith concert?

It was probably in 1971 when we got to play with Edgar Winter’s White Trash and Humble Pie at the Academy of Music in New York. We got 20 minutes. There were two shows a night, two nights in a row. Steve Paul, who managed Edgar and Johnny Winter, got us the gig because he wanted to see us. It was our first time playing on a big stage with top-level professionals. We thought, “Holy shit, man, this is great!” At one point, mid-set, we did a song called “Major Barbara,” where I sat down and played lap steel and Steven played harmonica. As soon as we got offstage, Steve Paul said, “What are you doing sitting down? You only got 20 minutes to get this audience off and make them remember who you are, and you sit down? I don’t care how good you are. You’re a baby band!” After that we might have cut the song out of the set.

The bottom line is, that show put us up against bands at the level we were shooting for. When Edgar played, Johnny came out halfway through the set and the place exploded. And then Humble Pie tore it up. It was an amazing experience, before our first record, before our first manager. It made me feel like, “Somehow we’re going to get here.”

Joe Perry's Gear

Guitars

Gibson Joe Perry Signature Model black-and-tiger finish Les Pauls

Gibson Joe Perry ’59 Les Paul

Gibson Custom one-off high-gloss black Les Paul (with Wilkinson tremolo and roller nut, plus a single Lindy Fralin Big Block humbucker)

Gibson Chet Atkins model tuned up a half-step (for “Janie’s Got a Gun”)

Three Fender Strats with left-handed Telecaster-style necks built by Scott Smith at Musikraft

Gibson Custom one-off “Billie” B.B. King Lucille model

Ernie Ball 6-string bass for “Back in the Saddle”

Fender Jeff Beck Esquire Tribute reissue

Fender Telecaster “parts” guitar tuned to E-B-E-E-B-E (for “No More No More”)

RS Guitar Works replica of a Guild Blade Runner

1950s Ozark (tuned in open A)

Echopark Ghetto Bird Custom

Echopark Joe Perry Model

Duesenberg Custom Joe Perry Model

Amps

Four modified Marshall JCM800 100-watt heads

Morris Mo-Jo head

Alessandro practice amp with 10" speaker

Marshall 1982BJH and 1982AJH 4x12 cabinets

Marshall 2x15 cabinet

Marshall late-’60s 8x10 cabinet

(All 12" Marshall cabs equipped with Celestion Vintage 30 speakers)

Effects

Klon Centaur

Duesenberg Gold Boost

Source Audio Reverb

SIB Mr. Echo (2)

TC Electronic Flashback

TC Electronic Vortex Flanger

TC Electronic Chorus

Electro-Harmonix POG

DigiTech Whammy

Pigtronix Distnortion

Dunlop Hendrix Wah

Rob Lohr Red Siren

Strings and Picks

Ernie Ball hybrid sets: (.009, .011, .016, .028, .038, .048)

Dunlop medium picks

Dunlop Joe Perry Boneyard slides—255 for lap steel and 256 for bottleneck

Is there a recorded solo that you feel is your defining moment as a guitarist?

There are two. The solo on “Walk This Way” put the capper on that song. The middle solo was just a taste of the melody, and the solo at the end was kind of structured. I play with that structure every night, and I like to think people relate to it. And then there’s “Dream On.” Live, that’s the point in the show where I try to see if I can blow up more amplifiers than I did the night before.

How did you get interested in using alternate tunings?

Aside from Bo Diddley, who played in open E, the older blues guys were my resource. I find open G gives me a whole different palette. It’s got a lot of strange places you can go, and some of my favorite songs are in that tuning. It leads me to play something outside of the box.

There are some songs I’ve written that we don’t play very often where I put my own tuning together, but I’ve written mostly around the open A tuning. I talked to Ry Cooder once about it and he said, “Listen, if you’re gonna play the blues, you’ve got to tune your guitar in D. That is the baddest key.” But everybody has their own way of getting to that sound. So I start there and make any adjustments I need. In a song like “Janie’s Got a Gun,” I tune the whole guitar up a half-step because I want to hear those open strings ring. You can’t do that any other way. I experiment, but my basic thing is G chord or A chord tuning.

You’ve had a lot of guitars over the decades. Is there a Holy Grail instrument that’s eluded you?

I’m still looking for a ’68 goldtop. The first Les Paul I bought was a ’68 goldtop. Now that’s a sought-after Les Paul, but I only paid $300 or $400 for it at the time. I’d love to have that guitar back—especially looking like it did before I scraped the gold off of it. I’ve got a couple of goldtops that are close, but that particular guitar is the one. One of the rumors is that after they stopped making Les Pauls in ’60 or ’61, and then started making them again in ’68, Gibson had a lot of parts left over. If that’s true, a lot of those pieces of wood were just sitting around the factory and got used. And the pickups were great.

I think the first goldtop I got had mini-humbuckers, but I’ve seen pictures where I’m playing one with P-90s, so I’m not sure which goldtop was the very first one I had. I was trading guitars a lot back then. We called them “midnight trades.” If somebody had a guitar I liked at the moment, I would just trade—that and a bag of pot. One night we played a show with the New York Dolls, and I remember trading Johnny Thunders a guitar for a two-pickup TV Model with P-90s. I loved the way it sounded, and I had something he liked, so we just swapped. That went on all the time.

That ’68 goldtop was the guitar you played on “Dream On” and the Aerosmith album?

I would guess that was it. But I also used a Strat an awful lot all through my career. Somehow a lot of our more outstanding songs featured my Les Pauls. But if Brad [Whitford] was playing a Strat, I would play a Les Paul, and vice versa.

Perry’s candid new autobiography (cowritten with David Ritz) covers the guitarist’s long career,

even periods he doesn’t quite remember.

Were their any now-obscure local musicians in the Boston and New Hampshire area who influenced you as a kid?

As far as the pros go, Jeff Beck and those guys were big influences, but there were some local guys I thought were amazing. There was one guy who took the frets off a Fender bass and put them on a Telecaster. It sounded almost like playing a sitar, and he’d put a lot of baby powder on his hands when he played. It was a really flipped-out style. His sound had that Mountain tone, but he never broke out of New England. I can’t remember his name, but the band was called Atlantis.

What’s your current favorite guitar?

I can’t quite decide if it’s my Strat or Les Paul. I have the relic version of my ’59 Les Paul that Gibson just did. I’m not taking my real ’59 out of the house anymore. Actually, I’ve put all my really nice guitars in a vault. The Strat I’m playing live is a reissue, too.

That tobacco burst ’59 Les Paul has an interesting story, doesn’t it?

Yes—1959 Les Pauls are spectacular instruments, and this was my first one. When I got it, it became my Les Paul, the guitar I depended on. But I sold it at some point in the ’70s for about $4,500 when I needed the cash. In 1984 when Aerosmith got back together, we decided to do the Back in the Saddle Tour. I got a call from somebody representing Eric Johnson, who told me that Eric had heard the guitar was mine, and he offered to sell it back to me for what he paid. I didn’t have the money at that point. I’d just gotten married and my wife was pregnant. I thanked him, though, and said I really appreciated the call.

A few years later we were working on the second album with Bruce Fairbairn [1989’s Pump] and I started to have enough extra cash to begin building up my guitar collection again. I thought it would be great to have that Les Paul back. I decided to track it down, so I started to make some calls, and some friends started looking for it, too. I was talking to Brad about it, and the next day he walks into the studio and says, “I know where your guitar is.” He shows me an issue of Guitar Player magazine, and there’s a story on Slash’s guitars. Right in the middle was a picture of the guitar. Not too much detective work involved in that! I recognized the guitar instantly because of the ring worn into the wood around the top volume pot.

YouTube It

Joe Perry considers the second solo on “Walk This Way” one of his defining performances as a soloist. In this version, an official live video from the Sony Records vaults, Perry starts that solo at 2:38 and spends the next two minutes pushing his flash to the fore—wailing through blues licks, playing behind his back, and generally delivering a primer in rock guitar showmanship.

I called Slash to talk to him about selling it back to me, and he said, “Oh man, please don’t ask me that.” I said, “I understand how you feel, but I’d really like to get it back.” We talked for a few minutes and before I hung up I said, “Let me know.” After a while, the calls between me and Slash started to get further apart. We’re good friends, so I figured it had to do with my trying to get back that guitar. Every time we’d talk, I dropped a hint, and I think he didn’t want to keep saying “no.” So when Steven and I sat in with Guns N’ Roses at a huge show outside Paris, I told Slash, “Man, if you ever want to sell that guitar to me, let me know, but I promise I’m not going to bug you about it, because I don’t want anything to get in the way of our friendship.”

In 2000 I was just about to go onstage and play with Cheap Trick—who are, like, my favorite band—at my 50th birthday party at Mount Blue in Hingham, Massachusetts, and I was handed the guitar with the message “Slash says, ‘Happy Birthday.’” I freaked! And I guess you know which guitar I played for the rest of the night. When I picked it up it all came back to me. I could feel the bare wood under my pinkie where the volume knob is. It triggered something. I instantly knew every inch of the guitar again without having looked at it for 35 years.

I guess Slash had only played it in the studio. When I called him to thank him, which I guess I did too many times, he told me three weeks after he gave me the guitar he’d gotten back one of his favorite top hats—it had been stolen—in the mail.