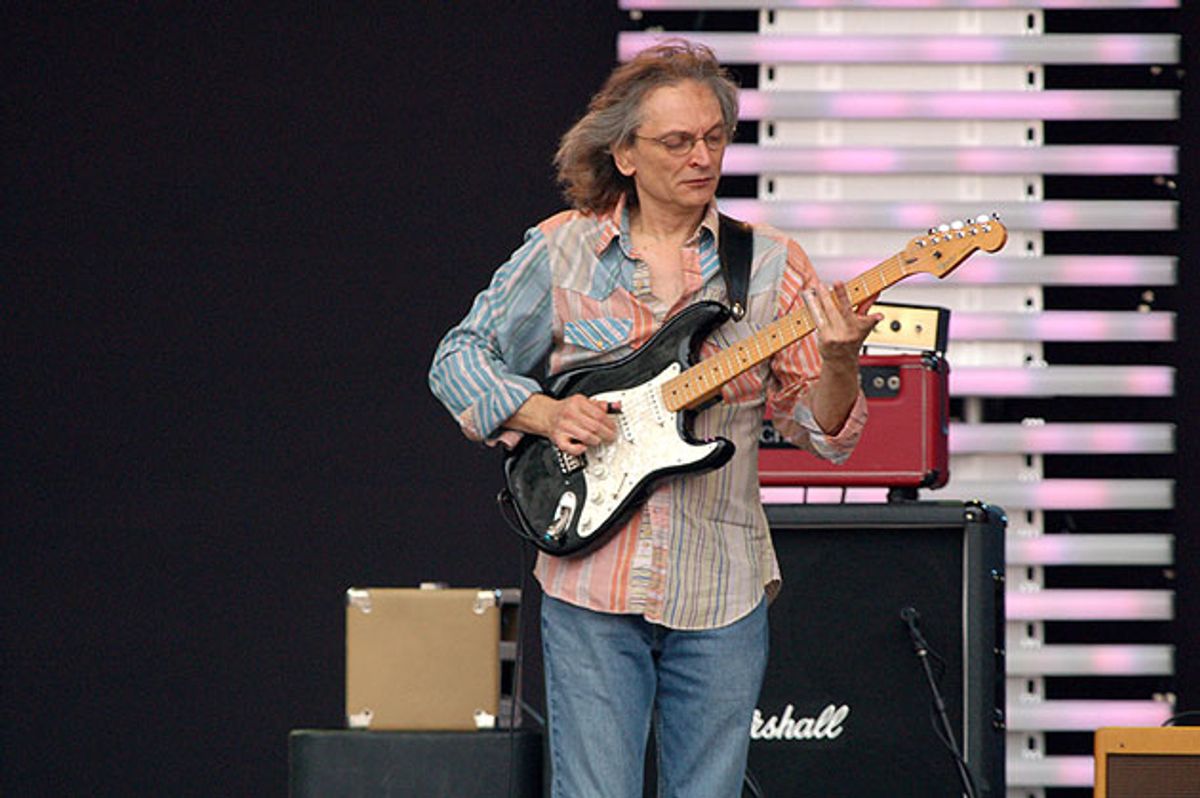

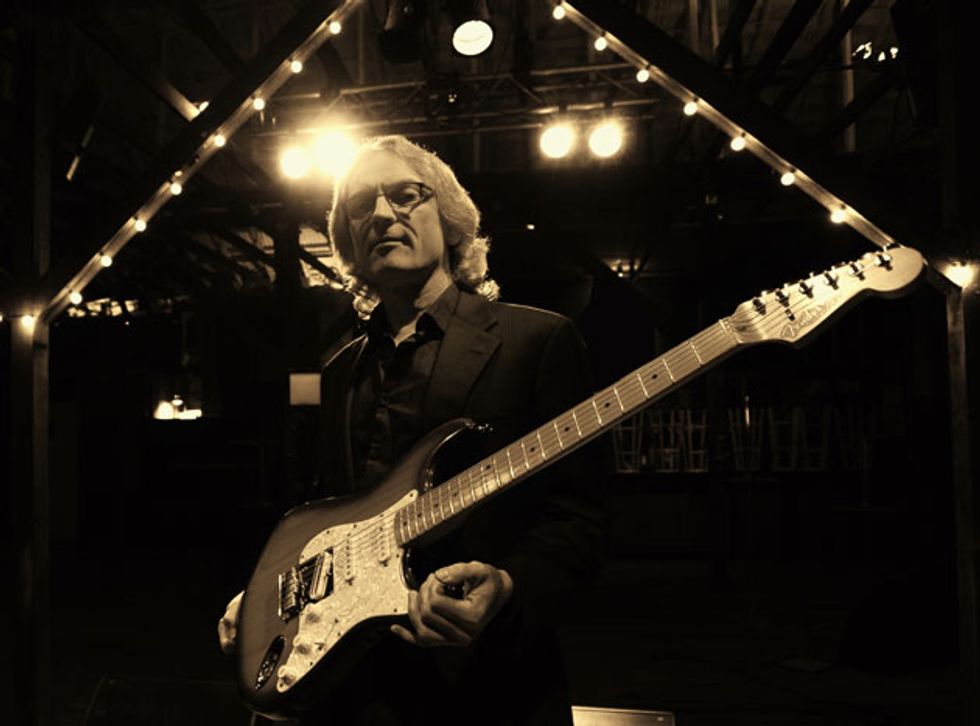

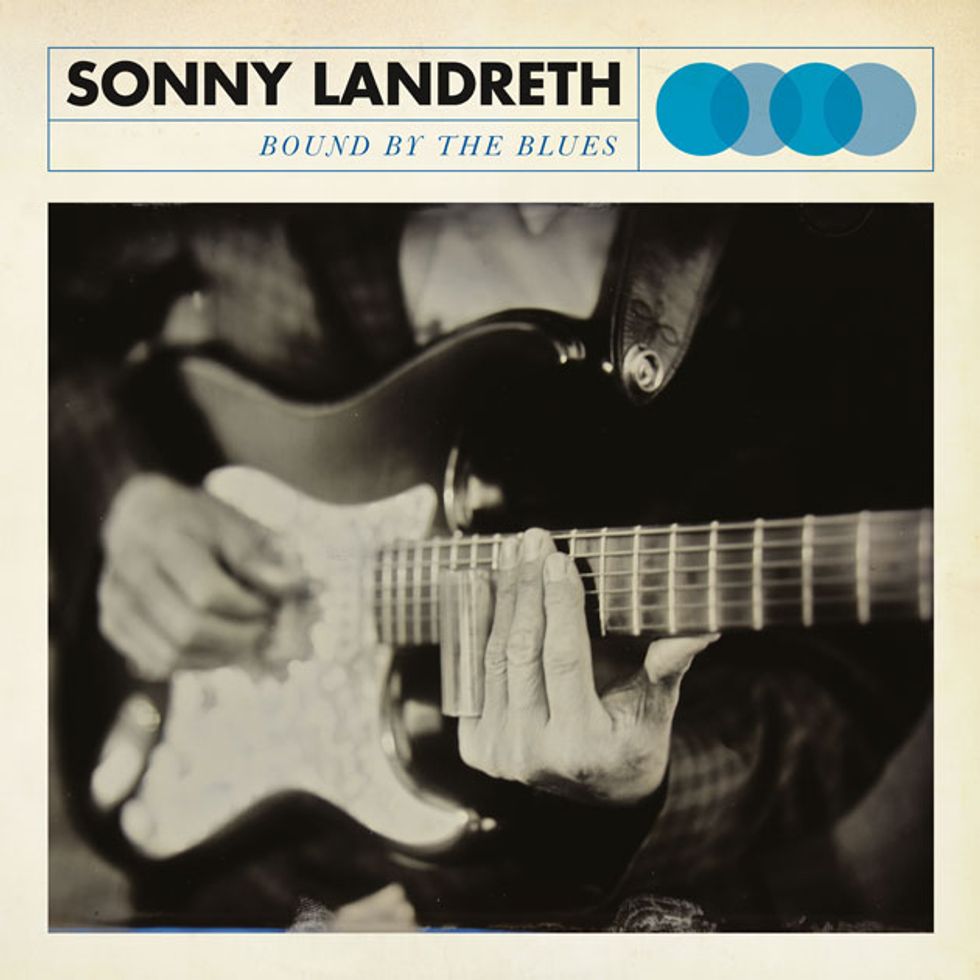

For his 12th album, Bound by the Blues, the slide wizard revisits the soulful sounds that launched his career.

There are plenty of mean slide guitarists, but no one has taken the bottleneck into such uncharted territory as Sonny Landreth. Using unorthodox combinations of slide and three fretting fingers, and an equally idiosyncratic picking-hand technique, Landreth can sound like a Cajun accordion, a searing Chicago blues harp, or a violin plugged into a screaming stack. But while he shines as a solo artist, Landreth is also one of the great sidemen, having toured or tracked with Kenny Loggins, John Hiatt, the late zydeco king, Clifton Chenier, and many others.

Born in Mississippi and reared in Lafayette, Louisiana, Landreth is a product of the South. As a boy in bayou country—a music-rich area that gave him easy access to the deep roots he’s always drawn from in his playing—Landreth soaked up Creole and Cajun sounds while studying classical trumpet at school and steeping himself in Scotty Moore and Chet Atkins. It was the perfect storm for Landreth’s catholic approach to the guitar.

As with many electric guitarists, the blues has been a catalyst for Landreth’s explorations. That soulful sound is always present in his playing, but was especially prominent on his first solo album, 1981’s Blues Attack. It’s also the focus of his latest record, Bound by the Blues, which Landreth recorded with a stripped-down trio featuring drummer Brian Brignac and bassist David Ranson. Bound by the Blues is a sharp departure from Landreth’s previous album, Elemental Journey, which included members of the Acadiana Symphony Orchestra, steel-drum legend Robert Greenidge, Joe Satriani, and Steve Vai.

Speaking from his home in Lafayette, Landreth explained how he uses the slide to tie together his eclectic influences, and how he approached writing and recording Bound by the Blues.

The title track of Bound by the Blues is evocative. What does it mean to you?

It makes reference to blues being the universal language—one that speaks to people everywhere—and to our challenges in the face of adversity.

In making this album, how did you put your own imprint on the blues?

That’s a very good question. Therein lies the challenge, and it’s exactly what attracted me to taking on this project. I decided to do another blues record because it had been a while, and it was so important to me. The music has always been a big part of who I am. Some of the songs I recorded have been done to no end, so I needed to bring something new to the table.

I love the surprises that can happen when I make an album. After more than 35 years of playing these songs—“It Hurts Me Too,” “Dust My Broom,” and “Key to the Highway”—with many different players, I found the tunes had taken on lives of their own. I realize how different I’m playing them now than when I first learned them. It struck me that as time has passed, I’ve subconsciously brought fresh sounds to the songs with new techniques and new discoveries that have happened along the way. It felt quite profound, and it was beautiful to circle back around to this music. It gave me a greater appreciation for who I am.

Landreth on the blues: “It was beautiful to circle back around to this music. It gave me a greater appreciation for who I am.”

How did you prepare for the recording?

The songs are standards for a reason. I really try to go deep to find out who originally played each one, who recorded it over the years, who ripped the other guy off, and so on. The next thing you know, you’re back in Africa, investigating words from tribes and dialects. The music becomes so much more complex and rich as a result.

Who were your musical benchmarks for this album?

I wanted to pay tribute to my heroes: Lightnin’ Hopkins, Muddy Waters, Jimi Hendrix. It would take hours for me to tell you about all my heroes. [Laughs.]

On the title track, you also name-check Buffy Sainte-Marie.

I’ve never really talked about Buffy Sainte-Marie’s influence, but she was such an important activist—she was right there with Dylan and all the other folk greats—and she really made different music. She’s Native American, and her work often deals with all the history that her tribe has been through, touching on things that are far more profound than what I can wrestle into a song.

Bound by the Blues has an old-school feel.

Not long before making the record I worked with a symphony orchestra for the first time, where I was exposed to very complex array of sounds. For the album, I did a 180-degree turn and used just a bassist and drummer. We went in and cut the record live, just like we play the tunes night after night in concert. Some of the tracks—“Where They Will,” for example, which goes back to acid rock—used just the three pieces: bass, guitar, and drums. But for the title track and a few other tunes, we used a little layering to get across the ideas and to build drama in the choruses.

The vocals sound fantastic—did you nail them live in the studio?

Due to allergies my voice was in really bad shape at the time we recorded the songs, so I had to re-sing a lot of the tracks. It was a lot of work, but it resulted in what are probably the best vocal tracks I’ve ever recorded.

Throughout, the record has some unusual sonic effects.

I wanted to get back to really cool, organic sounds. Instead of traditional drums, we sometimes used cardboard boxes for snares, or metal, or anything that seemed cool as a sound source for percussion. On “Dust My Broom,” Dave wrapped the neck of his bass with cloth, to mute the strings and get a more staccato sound. He also brought in a ukulele bass, and I couldn’t believe the sound he got from those nylon strings—it was so immense. We must have used the uke bass on four or five tracks.

What guitars did you use?

I used a bunch of different guitars to have different colors and timbres, and to keep things interesting. Robben Ford loaned me his 1958 Strat for a few years and I used it, tuned to D, on “Dust My Broom.” I also used my ’60 [Les Paul] burst in G tuning on “Simcoe Street,” an old 1930s National tuned to A minor on the title track, and a 1990s Dobro in D tuning on “The High Side.” And of course I played my old Gibson Firebird in some spots.

I assume the Firebird makes an appearance on the instrumental “Firebird Blues.”

I did use the Firebird on that track. Johnny Winters died when I was just about to make the album, and that hit me really hard. So it’s an instrumental tribute to Johnny with raw guitar, the cardboard box drums, and the ukulele bass. The Firebird is a real special one for me. Back in the day I played in an improv blues band and I bought the guitar from a buddy in the group. It must have been about 1971 or ’72. I played it for a long time, mostly fretting and flatpicking before using it for slide around 1980. I played the guitar extensively when I toured with John Hiatt in the late ’80s, but I don’t travel with it anymore. Unfortunately, overhead bins aren’t too friendly to guitars.

What’s special about the Firebird?

It’s got great sustain and rings like a bell. It’s so lively when played acoustically, probably because of its neck-through-body design. The pickups are the old mini-humbuckers, which have this unique sheen on the high end, not at all harsh. My Firebird works great for slide—it’s beautifully voiced for that. You can find sweet spots on the neck and just hold the notes forever.

Sonny Landreth's Gear

Guitars

Prototype Fender Signature Stratocaster with maple neck, DiMarzio Fast Track DP181 bridge pickup, and Fender Noiseless middle and neck pickups

Prototype Fender Signature Stratocaster with rosewood fretboard and Lindy Fralin Vintage Hot pickups

1958 Fender Stratocaster

1960 Gibson Les Paul

1930s National Duolian

1997 Dobro (with metal body and round neck)

Amps

Demeter TGA 3

Dumble Overdrive Special

100-watt Marshall plexi

Marshall 4x12 with Celestion Vintage 30 speakers

Fender Bandmaster 2x12 with Celestion G12K-100 speakers

Dumble 1x12 with Celestion G12K-100 speaker

Effects

Fulltone Tube Tape Echo

Hermida Mosferatu

Hermida Dover

Analog Man Compressor

Voodoo Lab Giggity

TC Electronic SCF Stereo Chorus Flanger

Strings and Picks

D’Addario EJ22 nickel wound jazz medium (.013–.056)

Dunlop 215 and assorted others

What other guitars have you been playing lately?

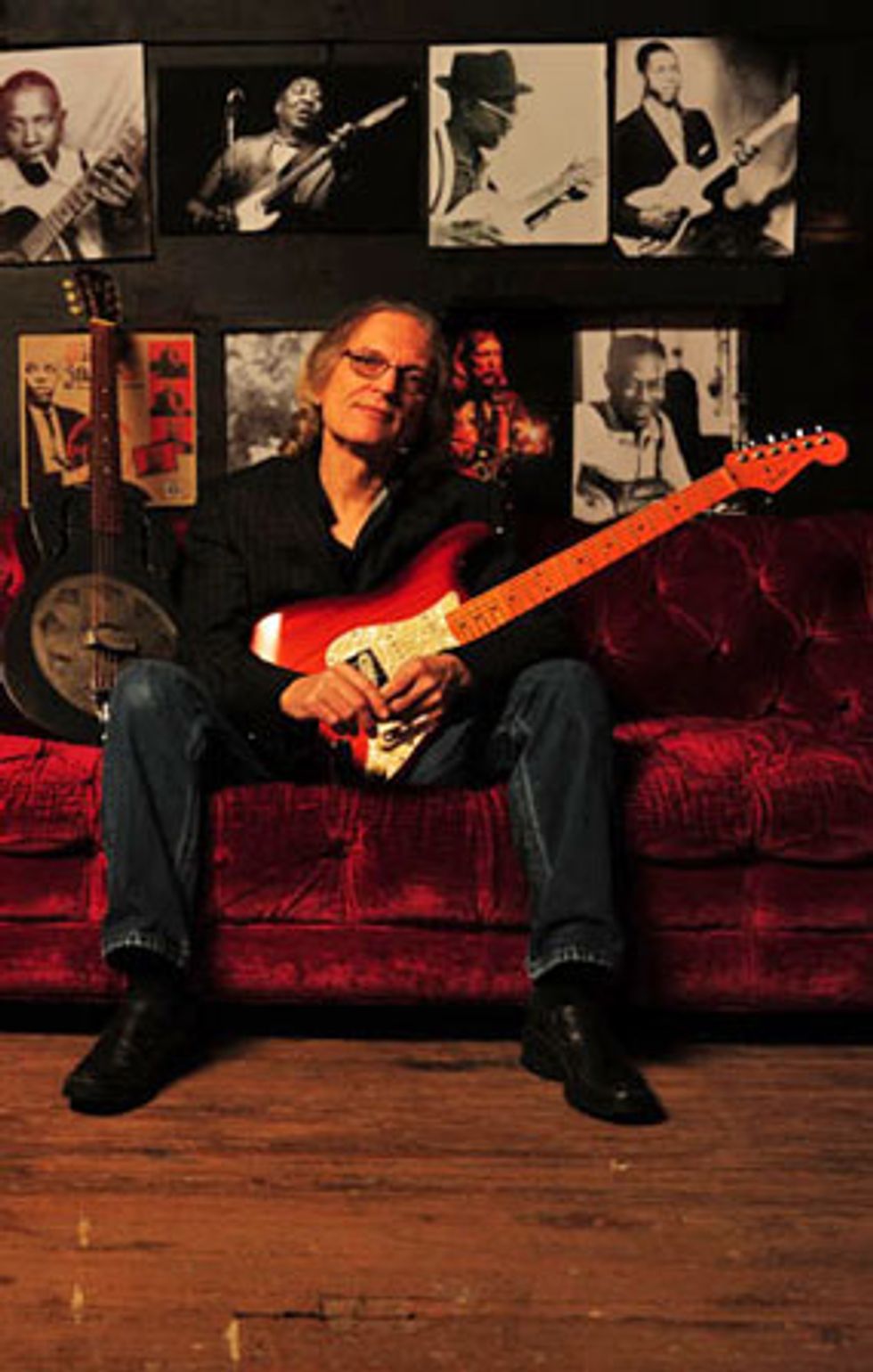

For the most part I’ve been playing Fender Strats—a pair of prototypes of my signature model. Working with Fender has been an epic project, going on for some years now. The neck on each guitar has a unique profile, made for what I like to play. They’ve both got a Telecaster bridge bolted onto a tremolo block for more sustain and character. One has a maple neck and the same DiMarzio [Fast Track DP181] pickup I’ve used for many years in the bridge. The other has a rosewood fretboard and Lindy Fralin Vintage Hot single-coils. I hope the guitars see the light of day by the end of this year—they work so brilliantly for slide.

Do you ever play without slide?

On some of my early albums, I did play without slide, but I haven’t done it in a while—at least not officially. Some of my friends heckle me about that. But for the time being, playing with Robben Ford or Eric Johnson, I let them do all that non-slide stuff. Slide is my true voice, but I do love playing without it, and so maybe some day I’ll get back to that.

Do you use alternative tunings exclusively? And how do you decide which tuning to use for a given song?

For the most part. Sometimes I gravitate toward a tuning that matches the key. If a song’s in E major, open E is an obvious choice. There’s so much you can do with the open strings, playing on top of them harmonically, melodically, and rhythmically, or playing on top of overtones to create sound collages for completely different textures. Other times, I might tune to a chord other than the tonic of a song. That way I can find all different kinds of cool nooks and crannies I wouldn’t find otherwise.

What’s drawn you to focus on slide for all these years?

Slide is a wonderful thing—it can really create a sound that emulates the human voice. I feel comfortable playing in a lot of different styles, and that’s great, but you have to be careful about going in too many different directions at once. In any case, slide gives me a focal point to catalyze all influences, sounds, and genres. It’s a tool to unify everything.

This prototype Landreth signature model Strat has a DiMarzio Fast Track DP181 humbucker in the bridge position and Fender Noiseless middle and neck pickups.

How did you develop your idiosyncratic slide technique?

It’s definitely a work in progress. New learning never ceases, as far as I’m concerned. One thing that’s helped me a lot is that I started on trumpet, so by the time I picked up a guitar, I had more of a wind player’s perspective. I had a natural sense of where to take a breath and a natural sense of melody. At the same time, I learned a fingerstyle approach in the Chet Atkins tradition while experimenting with the slide and learning blues. The slide has the potential to create lots of different sounds and colors with a vocal, soulful quality, and that set me on a path. Listening to the other musical instruments common in Louisiana, like fiddle and washboard, not to mention jazz, New Orleans second line, and R&B, I had such a great backdrop to draw from.

From a musical perspective, it must have been amazing to grow up in Louisiana when you did.

I grew up hearing all kinds of music: Creole, Cajun, blues, and jazz, and on the radio, pop and rock. I started playing trumpet at 10 and guitar at 13. I had strong jazz and classical influences at school, while I got to hear all my guitar heroes live. In my teens, I caught B.B. King and Jimi Hendrix at little clubs in Baton Rouge in the same year. All these influences combined to have a prodigious effect—they made me want to raise the bar really high and be open to all styles.

Your music features a lot of improvisation. What’s the extent of your jazz training?

Certainly not as deep as I wish it could be, but I do have some background in jazz. In college there was a course called jazz lab that gave students the opportunity to play big-band charts and bebop, and I had a great jazz guitar mentor who would help me with those charts. I certainly don’t consider myself a jazz musician—I don’t have the repertoire, I guess you might say—but the genre is definitely an influence.

Sometime I might want to take jazz head on, and also classical. I had a great experience when I worked with the Acadiana Symphony Orchestra. The conductor, Maestro Mariusz Smolij, came over from Poland, and he has rock ’n’ roll sensibilities. We just hit it off, and it was great to get into that world and apply slide guitar to it. For instance, it was so challenging and rewarding to play J.S. Bach on slide guitar. It gave me a completely different arena to work in, with lots of potential for new and exciting sounds.

YouTube It

Landreth brings his slide fire to an orchestral setting.

What advice do you have for aspiring instrumentalists?

Woodshed on the gig. As much as you can learn sitting on the couch, there’s nothing like playing in a band to take your playing to the next level. You learn to draw energy from the crowd, how to lead one idea into another, and to be open to whatever idea emerges. And you can learn a lot from your bandmates. It’s important to keep your antennas up to see how they do things, and to trust your intuition to put your own spin on things.

On electric guitar, one of the best things you can do is turn on your amp and just play. Eventually you’ll hit on something and think, “Where did that come from? I’ve never played that lick or tried that approach before.” That’s what’s inside of you, and you learn to trust it. The greatest affirmation is to learn from yourself.