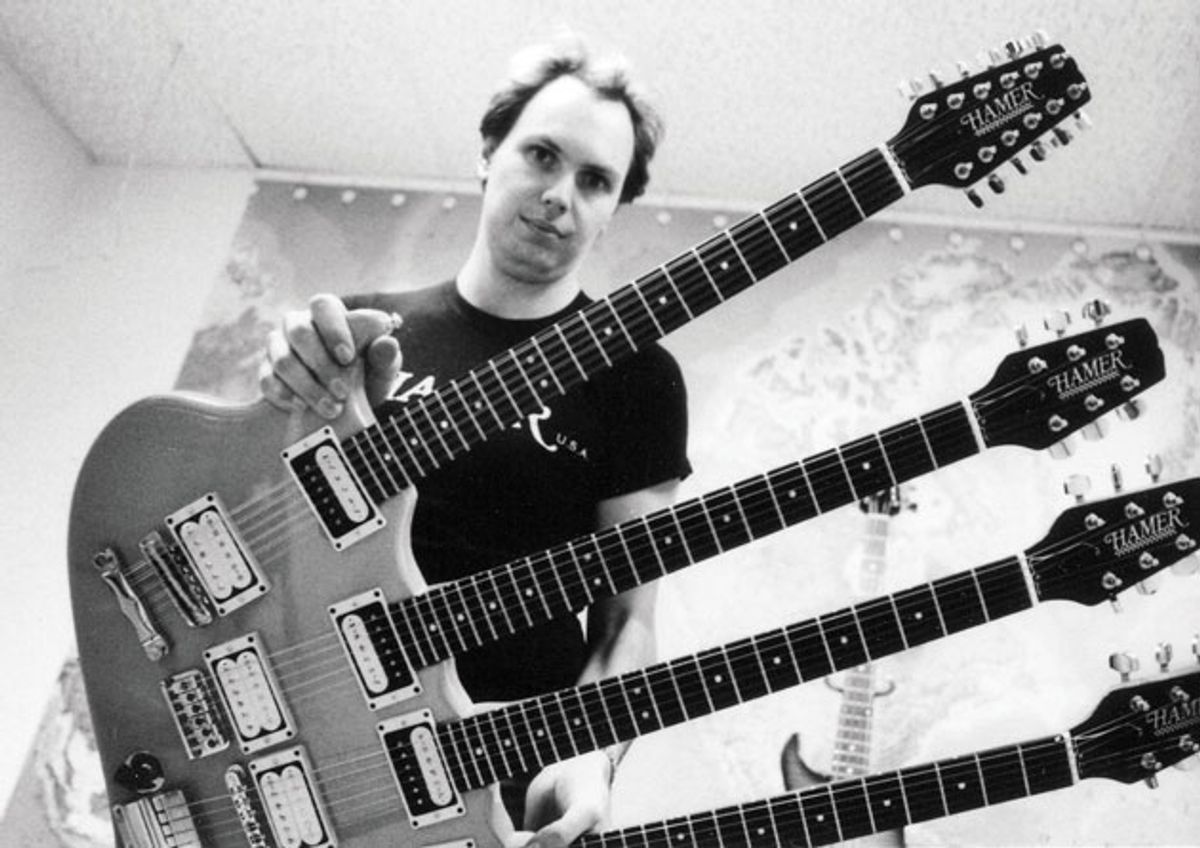

How a historic 5-necked wonder came to life in Hamer’s shop.

Sometimes you get lucky, but it pays to be prepared to wait. With the news that Cheap Trick has been nominated for induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame after 40 years of constant hard work, I imagine the band feels more dedicated than charmed. Let's hope that the Hall of Fame doesn't forget how truly unique Cheap Trick has always been.

I feel lucky to have been in the right place at the right time in 1981 when the phone rang and Rick Nielsen was on the other end of the line. By then, I'd gotten used to frequent brainstorming/request sessions with the Cheap Trick founding father, so I was not surprised when Nielsen broached the idea of a multi-neck instrument that would stop the show. Little did we know that this neck-heavy concept would be both a crowning achievement and an albatross around both our necks.

By the time anyone outside of the Midwest club circuit had heard of Cheap Trick, the Hamer guitar brand was well established in the U.S. and Europe. Bands such as Bad Company, Jethro Tull, Wishbone Ash, and many others were early endorsers, and shops around the world stocked our wares. Fellow guitar collectors Nielsen and bassist Tom Petersson were friends from the old days of prowling through pawnshops for vintage guitars on the cheap. The boys from Rockford, Illinois, were serious musicians and students of guitar history, but also great people with a decidedly serious sense of humor.

As Hamer resurrected the defunct and discarded Explorer shape in 1974, Nielsen grabbed one of the first and made it his signature axe. He recognized its lineage—the bastard son of a '59 Sunburst Les Paul and the rarely-if-ever-seen "lightning bolt" Explorer—and the guitar was perfect for his dual-citizenship personality. Despite its outsized appearance, we named it the Standard.

Before long, we'd constructed an entire fleet of personalized permutations for Nielsen, including a mandocello variation in 1977, the now-famous checkerboard-finished version in 1978, the "Coffee Table" graphic, and the early Floyd-Rose equipped "Yellowbird" in 1979. As the sight-gag graphics increased in number, the stature of Cheap Trick's fortune was growing even faster. The band had reached saturation on TV and radio by 1979, and they were dragging us right along for an epic ride. If there was any question about Cheap Trick's contribution to Hamer's exposure in the beginning, their massive success by the decade's end left no doubt.

When it was time to assemble the guitar, we realized what a behemoth it was.

It was while we were all riding pretty high that Nielsen inquired about the possibility of a multi-neck guitar to top all the others. According to Nielsen, he had originally envisioned a spinning guitar with six necks. But when ZZ Top appeared on TV with their spinning guitars, he changed his plan. He joked about wanting to outdo Rush, whose Geddy Lee and Alex Lifeson both brandished double-necks simultaneously. In order to do this, we'd need at least five necks. In retrospect, the conversation was surprisingly short, and Nielsen left the fine details in my hands.

I walked back into the shop and flagged down the foreman, Steven Ward, to give him the overview. Because Nielsen wanted the guitar immediately, I decided to forgo the usual practice of creating drawings. We figured we'd use some existing bodies from the production rack so we could push the build ahead a few days. Steve and I laid out five Hamer Special body blanks right on the shop's enormous table-saw bed. We jockeyed the bodies around, stacked them on each other, and I marked out cut lines with a straightedge and pencil.

The challenge was to remove the parts of the bodies that had control routs, but still make it look like a usable guitar. Steve brought over a few raw necks so I could be sure of the headstock clearances. It was going to be tight. When we were sure things looked good, Steve got to work on the bandsaw. We then mocked up the assembly, I drew out the control locations, and sketched the swoopy blends right on the blanks between the necks so that Steve could finish up and bond them all together. The whole exercise took just a few hours.

Meanwhile, I went into the paint room to mix up a nice opaque-orange lacquer that would hide the multi-piece nature of the body and be bright enough to be seen from the last row in a stadium. After the necks were glued on, Steve drew the instrument's outline on brown craft paper to send to the case manufacturer before carrying the guitar into the spray booth.

When it came time to assemble the guitar, we realized what a behemoth it was. Each set of pickups and tuners added to its already hefty weight. After the last string was tuned, I took a few photos and put the guitar into the case to be shipped out immediately. I remember thinking that the guitar was pretty funny, but I had no idea how significant it would become.

My career has been dedicated to making instruments for serious musicians, regardless of how they choose to express themselves. I was proud of the way our team had produced the 5-neck guitar quickly for Nielsen, and how it became such an important part of Cheap Trick's show. Still, there was a stigma attached to it. Some people didn't get the joke. For awhile, I thought the 5-neck's cartoonish nature somehow overshadowed our artistry and the band's music—until it was displayed at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston in 2000. The now-famous orange guitar hung in a space where great works from the likes of Hockney, Hopper, Calder, and Monet are displayed. I guess the joke is on someone else now, and it was worth the wait. I hope Cheap Trick feels the same.

[Updated 10/8/21]

- Rig Rundown - Cheap Trick - Premier Guitar ›

- Cheap Trick: ... But Don't Give Yourself Away - Premier Guitar ›

- Rick Nielsen: His Checkered Past - Premier Guitar ›