To create their new album Purple, Baroness' new line-up relied on collaborative songwriting and a determination to forge a personal sound from spare chord forms, low-wattage amps, and scores of stompboxes.

After surviving a harrowing wreck, the band returns to reinvigorate modern metal with Purple, a distinctive two-guitar exploration of partial chord voicings, low tunings, and low-gain amps.

Purple, the title of Baroness' latest release, symbolizes the bruise that the band suffered after their third studio album, Yellow & Green. That groundbreaking double-disc set hit number 30 on Billboard's Top 200 Albums chart and earned the inventive Savannah, Georgia-based metal outfit a spot on plenty of “year's best" lists. But in August 2012, less than a month after Yellow & Green came out, Baroness' tour bus fell off a viaduct near Bath, England.

Three members were seriously injured and it was nothing short of a miracle that they all survived. Frontman and guitarist John Baizley's left hand was crushed—with bones breaking through his skin. Drummer Allen Blickle and bassist Matt Maggioni suffered fractured vertebrae. Lead guitarist Pete Adams fared the best, with only minor injuries. The recovery process was slow and painful, but by early 2013 they were well enough that a tour was planned. Blickle and Maggioni, however, were still reeling from the accident and amicably departed, ending a collaborative relationship that had been intact since the four friends formed Baroness and split their hometown of Lexington, Virginia, in 2003.

Left with half a band, Baizley and Adams faced a fight or flight situation. But if broken bones hadn't stopped them, this sure as hell wouldn't. They recruited bassist/keyboardist Nick Jost and drummer Sebastian Thomson solely on recommendations from friends like Mastodon's Brann Dailor—no auditions were held—and the current incarnation of Baroness was born. On the surface, it's an unlikely pairing. Jost has a master's degree in jazz composition and Thomson is renowned for his work in the electronic music scene, in addition to founding the rock band Trans Am. The new rhythm section was immediately thrown into the fire when Baroness embarked on a nearly yearlong world tour.

When it came time to write Purple, a fresh dynamic came into play. “I think the challenge was, 'How are we going to do this without killing each other?'" says Adams. “We're all sitting in a room trying to write music together and, for me, it was very frustrating at first, with the new members. Trying to write as a four-piece—I think a lot of bands probably share the same opinion—is difficult."

The songwriting process ended up taking about a year, with a chunk of the time spent trying to connect musically. “We wanted it to happen immediately, but it took a month," Baizley recalls. “Once we clicked and could feel the energy surge and sense the connectivity in the rehearsals, then the writing took on its own flavor and we let it happen."

Purple, produced by Dave Fridmann (The Flaming Lips, Tame Impala, MGMT), is the band's most personal release to date, as well as another free-ranging addition to their distinctive musical cannon. Songs like “Chlorine & Wine," “If I Have to Wake Up (Would You Stop the Rain)," and “The Iron Bell" draw on their brutal recovery period. But Purple also showcases Baroness' unique ability to create an almost orchestral flavor—exploiting their two-guitar texture in colorful sounding, harmonically adept, rhythmically risky, and hauntingly melodic ways too rarely heard in modern metal. Baizley and Adams spoke with Premier Guitar about all of the above—and more.

Do you twist things to make your songs more complicated?

Baizley: We're trying to be slightly progressive without crossing the boundary into prog too much. I don't like repetition, even when the structure is literally the same. Say there are four phrases that comprise the verse in a song. Each one of those phrases will have slight differences. It's like, “Sebastian, why don't you try playing 4 and we'll try to ignore you so we can play this thing that's got an odd phrase length on top."

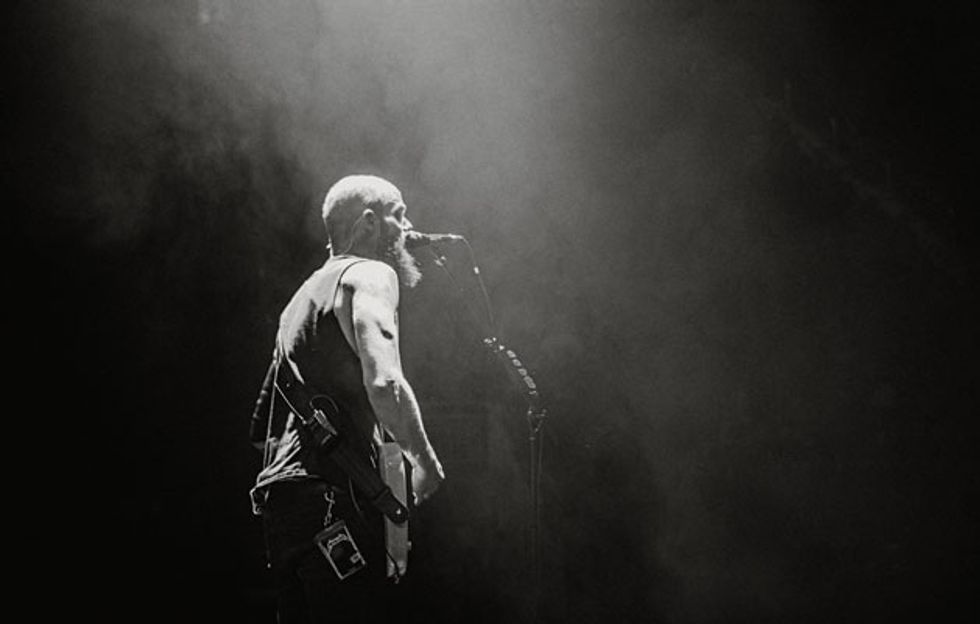

Lead guitarist Pete Adams embodies the explosive energy of Baroness' free-ranging sound when he takes the stage with his late-'60s Les Paul Classic.

We kind of drove him crazy at first, because he's very mathematical. He maps things out the way that they're supposed to be mapped out. There's a lot of times on the record when we'll move rhythmically from 3 to 4, 7 to 4, or 5 to 4—whatever, for a moment. If the drummer is changing his feel, it's the responsibility of the guitar player or bass player to keep the rhythm very, very tight.

As complex as the music gets, it sounds quite organic.

Baizley: It's got to feel good. I want to play music that's challenging and that musos, or whatever you want to call them, can find those layers in. But at the end of the day, a good song is a good song. Who cares how simple or complicated it is? There's got to be moments where average listeners—somebody who doesn't even understand 90 percent of this conversation we're having—can enjoy it on their own terms.

What challenges did you have writing with Nick and Sebastian?

Adams: The first challenge was to figure out the strengths and weaknesses of the new musicians, who are both actually very strong. We tried writing as a band, and I don't know if it worked for anybody. So John and I would come up with ideas, and John would sit down with the new dudes, throw out those ideas, and let them chew on them for a little bit to see if something came out of that. I would rejoin once they knew what the hell was going on with the songs. You take the good stuff and see if you can't capitalize on it. That seemed to work.

Why did you choose to write as a band instead of you and Pete writing and telling the new rhythm section what to play?

Baizley: Really simply put, we're just not that kind of band. It has always been of the utmost importance to us that we avoid that kind of songwriting process. It's got to be a collaborative effort.

Adams: I want everybody to have his two cents. I really do. I don't desire to be in a band where you have a primary songwriter. That doesn't appeal to John and me.

John Baizley recalls, “Once we clicked and could feel the energy surge and sense the connectivity in the rehearsals, then the writing took on its own flavor and we let it happen." Photo by Jimmy Hubbard

How do you communicate honestly without offending the other members?

Adams: If you're wondering who does the checking in this band, it's totally me. I'm like quality control sometimes. I gotta get in there and go, “Hell no. We don't do that. That's not how this shit works." And I don't mind saying it. Because John and I both have a vision for Baroness—and even between John and I, we might have two different visions.

Was it awkward dealing with Nick's drastically different background in jazz?

Baizley: I think one of the important things to do from time to time is to engage in a little awkwardness. How can you make a breakthrough if you don't go outside your comfort zone? It's through an understanding of how to do that correctly that you can discover things. Nick would not have joined the band if he had that really, really orthodox, hardheaded approach I'm sure some of his peers and companions in the jazz scene do.

Adams: When I first met Nick, the first thing he asked me was, “Could you turn me on to some new music that really influences you?" He wanted to know where we were coming from and he wanted to try to meld into it the best he could. That was pretty incredible. He really wanted to do the right thing, and Seb did too. Neither of these guys was terribly familiar with Baroness, and to top it off, neither of them comes from a hard rock background in any way. Seb went from writing dance beats on a computer to playing this. He's an incredible drummer.

John Baizley's Gear

GuitarsG&L ASAT Special

G&L ASAT Alnico S-series

G&L Legacy Series S-Style

1962 Gibson ES-330

Rockbridge 00 acoustic

First Act Custom

Amps

Fender reissue'65 Twin Reverb

Fender reissue'68 Custom Princeton Reverb

Premier B-160 Club Bass

Roland JC-120

Vox AC30

Effects

Tym ODP/666 overdrive

MXR Super Badass Distortion

Philly Fuzz Klon Centaur clone

Philly Fuzz Heretic Fuzz

Philly Fuzz Martyr Fuzz

Strymon TimeLine delay

Strymon Mobius modulation pedal

Mu-Tron II Phasor

MXR Custom Shop Phase 99

Retro-Sonic Compressor

Mr. Black Thunderclaw overdrive

Electro-Harmonix Big Muff Pi (bubble front)

Electro-Harmonix Memory Man

Death By Audio Echo Dream

Tym Big Mudd (Ramshead series)

Spaceman Spacerocket Fuzz

Schumann PLL analog harmonizer

Knas Ekdahl Moisturizer reverb

Ernie Ball Volume Pedal

Dunlop Fuzz Face

MXR Blue Box

Electro-Harmonix Pog II

GigRig G2 switching system

Strings and Picks

D'Addario custom (.010-.049)

Dunlop Orange Tortex .60 mm

Pete Adams' Gear

GuitarsGibson Les Paul Classic

First Act Custom “Green" Matamp

Budda Superdrive-80 Series II

Effects

Fulltone OCD

Maxon AD-999 analog delay

MXR Phase 90

Dunlop volume pedal

CMAT analog chorus

Strings and Picks

D'Addario custom (.010-.052)

Dunlop Nylon .88 mm

“If I Have to Wake Up (Would You Stop the Rain)" uses some diminished chord voicings in the intro. How did you come up with those?

Adams: That song was largely conceived by Nick. The voicings were one of Nick's things. He was messing around with an idea that he brought into the rehearsal space, and threw it at John. John dug what he was doing, and they started to build something out of that.

The intro vaguely resembles the jazz standard “My Funny Valentine."

Adams: There you go. Now we've gone from being a band that's influenced by the same bands to four dudes in a band who are wildly influenced by everything out there.

There are also a lot of other sonorities, like fingerpicked tenths, in your music that aren't common in metal.

Baizley: I didn't really learn those intervals. I have no real formal training. From a very early stage in my musical career, I had a desire to push back against conventions. As we started Baroness and realized what the format was at the time—high volume, high energy, very low tuning—we wanted to try to find new things that, on paper, theoretically, shouldn't or wouldn't work. But because we've got our own sensibilities, we'll figure out how to make certain things work. I would stumble upon these strange sounds.

Pete and I spent a lot of time developing this system of playing guitar whereby I would play a strange two-note chord—like you said, a tenth or a ninth—and Pete would find a similarly shaped chord, but with different notes. We realized that rather than have each one of us try to build these dense chords, we could kind of create them in a stereo format.

So you'd play two notes and he'd play two different notes of the same chord?

Adams: That's exactly what we do. We always want the two guitars to have their own voice in the band. If one of us writes something on guitar—and it almost doesn't even matter what it is—the first thing the other person is doing is looking for the piece to accompany that. When we write a riff, verse, chorus, or whatever, we're like, “Here's the part. Throw your two cents on it." We have two guitars, so that's 12 strings between two dudes. Let's use all 12 strings.

Baizley: If you were to hear just the chord I was playing, you'd recognize it as sort of a major 7. If I were playing the rest of the notes, that's what it would eventually be. If you listen to what he's playing and what I'm playing, you'd hear two very dissimilar feels, but when you mesh them together, there's a sort of forgiveness that you get for some of the contradictory notes. Through that, we're inverting all of our chords all the time and coming up with this sonic bed on which, vocally or melodically, you could choose several different pathways.

That's refreshing, because many bands just have two guitarists doubling the same parts.

Adams: That makes zero sense. Fire that dude, you don't need him [laughs]. Every band's got its own thing and that's fine. We always liked the two guitar bands that play off of each other. Like Dickey Betts and Duane Allman—that's my shit, man. I grew up on that sound and that feel.

Baizley: Pete and I have always been very interested in melody and harmony. We try to create different types of harmonies and melodies that work, have a familiarity to them, and pay respect to music that we like. But that also have a newness and a playfulness. Because the important thing is that sometimes we don't understand what we're playing. It has a sound that we like and seems to lead us in a direction.

“From a very early stage in my musical career, I had a desire to push back against conventions," says frontman John Baizley. “As we started Baroness and realized what the format was at the time—high volume, high energy, very low tuning—we wanted to try to find new things."

But “Chlorine and Wine" exhibits a clear, sophisticated harmonic sense. There's a cadential harmony at the end of the intro that has an almost classical sound.

Baizley: It's Am–C–Am–F–Am–G—a really classic set of chord forms. That song is downtuned a whole-step. I always have to transcribe stuff because we play a whole-step down and we have a jazz bass player who won't tune down. And I have to tell him what the actual notes are, but to me, they just are what they are on the neck.

Primarily we keep our guitars tuned in what we call D standard, but we also do a drop tuning. Very frequently—in the past, not so much on this record—the 6th string is tuned down to a C. So it's basically a whole-step down from dropped D. So barring is easy, and if you take the root note on the D string and add a second to it, and a third, and a fourth, and you just move your pinky up from that root, you can start to build these chords. I'll play a strange sounding power chord with a minor or major inflection on it. Pete will then play a reverse version. A lot of times we won't use the root note as the lowest note—we'll use the 3 instead.

So you're playing inversions of the chords?

Baizley: Yeah, inversions. It's fun because half of the time we stumble into it. We don't intentionally do it.

John, you use guitars uncommon in metal—a Tele-style G&L with P-90s and a 335-type—while Pete, you use a Les Paul. Are you doing that to get contrasting tones?

Adams: Once again, we've got two guitars and 12 strings. So we went for different sounds. My sound is a Les Paul with a pair of '57 Classics. I like a slim-taper neck on my Les Pauls.

Baizley: I mostly play G&Ls, so it's almost all single-coils and P-90s. Pete's sort of the definitive Les Paul player. That sound works so well for his playing and it's so obvious to me that he's comfortable in that range. I used to play one, too, and we used to have a similar rig, but I started to get uncomfortable about how similar we sounded. Even though we have vastly different musical personalities. When we need to be synchronized, surely we'll be synchronized—like when we're both playing rhythm—but at the end of the day we really should have two different instruments.

YouTube It

Baroness lays down the smart 'n' heavy at England's Live at Leeds festival in August 2015, delivering an early taste of the Purple album with the song “Chlorine and Wine." Check out John Baizley's and Pete Adams' signature harmony leads at 2:22, as well as Baizley's trippy vibrato

John, since you're not using humbuckers, do you use a lot of gain to get that massive tone?

Baizley: Neither Pete nor I really enjoy using that much gain, which sounds funny, but it's true. We stopped playing the Marshall-y kind of amps early on in our career. Our gain or drive sound is entirely pedal based. I have somewhere between 250 and 300 pedals and each one has its own specific color. We use our amps on very clean settings.

Adams: The “Green" Matamp has the best, booming clean. [Editor's note: Matamp founder Matt Mathias worked with Peter Green's Fleetwood Mac in the company's early years, and designed the amp used on “Albatross" and other Green compositions.] I'll use either that or the Buddas for cleans.

Baizley: Right now my main amp is a '65 reissue Fender Twin. I also use a Princeton, which is absolutely one of my favorites. I just need to figure out how to make it work on the road. It'll be difficult because it's not very loud. One of my hidden weapons is a Premier B-160. It's a company that was around in the '60s. The tubes and speakers are original and it is absolutely on the verge of blowing. I've never heard an amp that sounds this good.