Guitarist Arian Shafiee dances on a musical high wire. His partners: a Strat, a Kramer, a trick bag of effects, and radical compositions with no boundaries.

Musical magic tricks that don’t rely solely on flashy production have become increasingly rare. But with the eight sonically surprising art-rock triumphs comprising their latest album, Eraser Stargazer, Guerilla Toss has emerged as something of a musical Ricky Jay. With a style that defies easy comparisons, the Brooklyn-by-way-of-Boston group displays an ability to create dance-worthy, approachable, and abundantly fun songs out of the complex elements that make experimental music challenging. And they make it seem as easy as cutting an orange in half with a flung ace of spades.

Eraser Stargazer, the band’s fourth full-length, is an adventurous, exuberant work that plays like a cartoon soundtrack. Atonality and harmonic quirks effortlessly meld with heady, jazz-informed rhythmic complications and off-kilter funk, but the result is far from the overwrought compositions that mix of ingredients might imply. Think instead of a deliriously joyful Carl Stalling composition—on acid.

The members of Guerilla Toss are a well-educated bunch whose core met at Boston’s New England Conservatory and work hard for their music’s seamlessness. Add in a slew of albums released on notable labels from throughout the experimental and outsider musical spectrum (including 2013’s Guerilla Toss on famed New York City avant-garde lynchpin John Zorn’s Tzadik Records), roots in the punk community, and a frantic, audience-enflaming live show that’s grown its own legend … and Guerilla Toss represents the vanguard of art-rock in 2016.

Arian Shafiee is charged with handling guitar duties for the group. He’s both a lifelong student of the instrument in the traditional sense and an anti-hero of the 6-string in Guerilla Toss. Shafiee is a product of unexpected and disparate influences that range from classic rock to technically challenging Norwegian black metal. To say his approach is unconventional would be a massive understatement. For example, Shafiee claims he didn’t bother tuning his guitars when playing with Guerilla Toss until around 2015—five years into his tenure.

Following the release of a new companion album to Eraser Stargazer called Live in Nashville, we recently spoke with Shafiee about his journey as a player, how he pens parts that rise above and support Guerilla Toss’ formidable din, his unconventional approach to creating atonal rhythms, playing chords like a drummer, and his perspective on music education.

What was your path into the guitar? Where do you come from as a player?

I grew up in San Francisco and found my mom’s electric guitar hanging in the basement when I was kid——it was some off-brand—and I just had a magnetic attraction to it and played it all the time. From there, I got into Sabbath and Led Zeppelin, and eventually found myself doing a live performance of Van Halen’s “Eruption” at the 7th grade talent show through a bass cabinet I found in a friend’s closet.

A few years of the typical classic rock shredding many young guitarists are attracted to eventually led me to outside players like Zappa and Sonic Youth—people that broke the rules a lot—and that’s when I started trying out weird, extended technique type stuff. Now I’m back into classic rock, so it’s all a big cycle.

I had friends that wanted to play jazz, which was kind of square to me then, and friends that wanted to play in garage-rock bands, but they were all guitar players, so I defaulted to playing drums. So, as far as guitar went in my formative years, I would play weird, prepared guitar and experimental shit by myself, and I did that for years without really telling anybody.

Eraser Stargazer, the band’s fourth full-length, is an adventurous, exuberant work that plays like a sonic cartoon. Think of a deliriously joyful Carl Stalling soundtrack—composed on acid.

Could you tell me who influenced you?

I listen to and love a lot of black metal, which informed my technique, because I was always trying to do a lot of the techy stuff that’s a part of that sound. That said, I feel like I’ve had the same technique or amount of chops since I was 17, and haven’t grown much since then.

I got hip to bands like Darkthrone and Mayhem pretty early on, but was simultaneously listening to terrible pseudo goth/extreme metal—think Ozzfest circa 2003. Yikes! So, it all informed my technique and playing. Mostly the tremolo picking and stamina that requires, arpeggiating angular flourishes of notes, and lots of down-tuning. Later on I got more into bands like Enslaved, Emperor, Mütiilation … anything out of the Les Légions Noires-era is truly amazing—all of the French outsider black metal, which all seems to be presented with terrible audio quality, but is full of beautiful harmonies.

I pull from all different styles of music when I play in Guerilla Toss. As time goes on, things have gotten funkier, and I’m using more traditional funk chords, like E funk chords, occasionally. But most of the stuff I do is gestural. I didn’t start actually tuning my guitar in this band until about a year ago.

So you’d just roll with the tuning how it was?

When you hear super weird, skronky chords in our music, that’s me playing exclusively with rhythmic elements instead of forcing more harmony into the mix. Guerilla Toss has a really wide sonic range; there’s a ton of crazy low end and high end coming from the synths and keyboards. And we run our drums and keys through a sub we carry with us on tour, so there’s just so much going on that sometimes a guitar melody isn’t the best thing to speak over all of the sound. Sometimes the only thing that speaks over all of it is harsh, basic anti-chords in a really high register just being bashed out.

I hear a lot of that chordal density and tremolo picking stuff in Guerilla Toss’ music, but would never expect black metal to come into the picture!

That’s just the way I play. There are definitely a lot of ideas that come through during the writing process that I can’t always express, because I can’t really play that chord or that idea, but I can find a way to do it with an alternate form or gesture. Also, a lot of ’70s New York no wave stuff stuck with me and had a big influence on my playing. All of the really wide chords you hear in Guerilla Toss’ music ... if it sounds super harmonically complex, it’s because I came up with weird shapes on a visual level and just stuck with them until they worked somewhere. Guerilla Toss has a very wide palette: Two keyboards—often blasting sub-bass tones, drums that use triggered sounds, auto-wah bass guitar. Playing simply with gesture and register is a way to make musical figures speak loudly over the tons of layers and texture this band plays with. I often like to think of drums when playing sharp angular patterns, reducing a line or contour to just “high,” “middle,” and “low” registers, and I push the focus more towards the rhythmic aspect of the part. I down-tune to dropped C most of the time, which gives the rest of the strings a little extra slack, making it easier to latch onto random shapes.

YouTube It

Guerilla Toss brings the noise on its Brooklyn home turf at the now-shuttered club Palisades. Check out the edgy, staccato riffs Arian Shafiee picks out of his Fender Stratocaster when the Easter Bunny arrives. As the performance comes to its skronk-guitar conclusion, it’s clear this is not your average noise band.

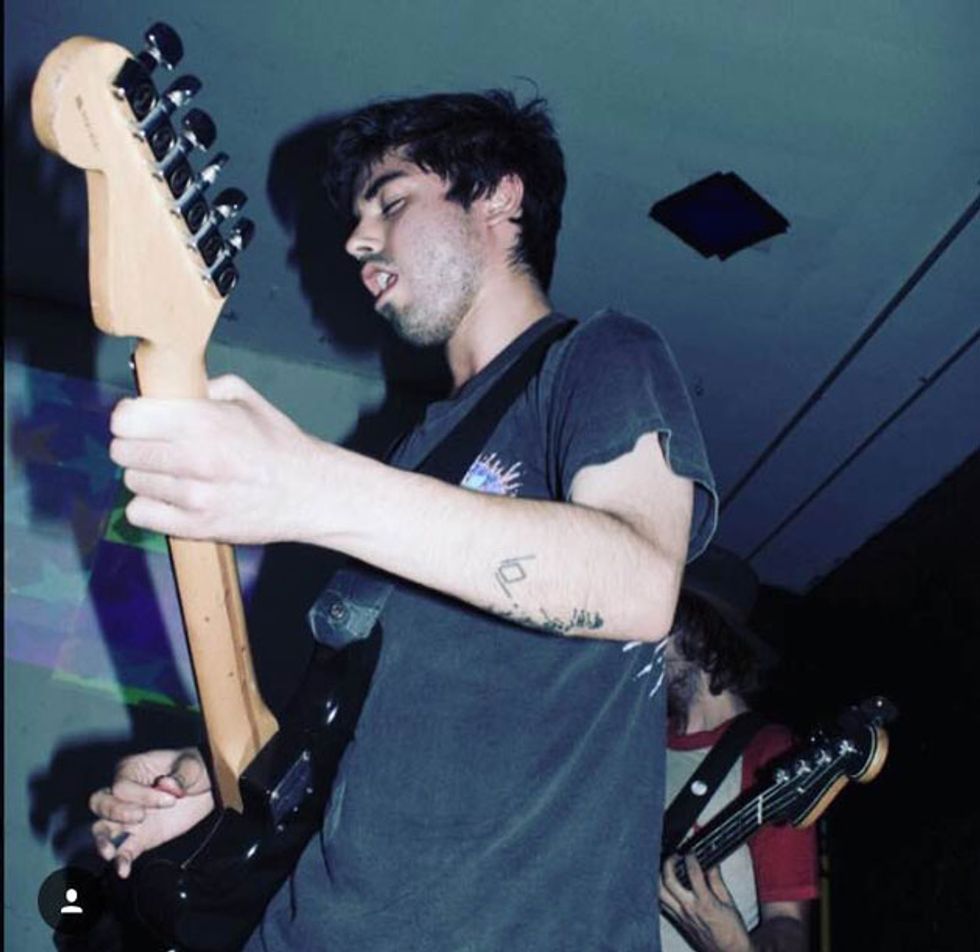

Shafiee wields his American-built Fender Stratocaster as he performs in a low-ceilinged club with new bassist Greg Albert at this back. Guerilla Toss plays comfortably in both art spaces and punk rock rooms.

There are a lot of atonal, anti-melody rhythmic ideas that seem to add more to the band’s percussion than what a guitar would normally do.

It’s tricky sometimes, trying to stay fresh on the guitar and trying to reinvent yourself, but serving the song is a very important part of what I do. It’s often important for me to blend my parts in as reinforcement for a keyboard or drum part, which is much more important than just shredding.

Does the band have a process for songwriting?

We literally sit in a room together and dissect ideas for hours. I assume most people write like us, at least those in collective band settings, but we’ll spend four hours at practice on writing 30 seconds of music—which can be disheartening sometimes, but that’s the way it goes. One person typically brings an idea in and we’ll jam on it together until something really sticks, which I feel yields the best material. We also work together on sections a lot and try to string stuff together. The music usually comes pretty quickly and the structuring and form is what takes a lot of time. We never want to be the band that just does a verse/chorus/verse, predictable thing. We’ll do an A thing and then an A prime into a B section, and then we’ll do the A section again, but half-a-time through, and we work really hard to come up with micro-variations that aren’t too overtly complex, but are intuitive, interesting forms that don’t take away from the songs being danceable.

Are your bandmates super-educated players? It sounds like everything is highly deliberate.

We’ve all been playing music for quite some time. Peter [Negroponte, drums and production] and I met at the New England Conservatory in Boston, along with our keyboard player Sam [Lisabeth], who joined the band later. But that’s how we got together. And Kassie [Carlson, vocals] didn’t go to music school, but she plays classical violin and has deep chops on that, so we’re all well trained in one way or the other. Kassie brings a lot of intuition to the table and just gets it.

It’s easy to assume that a conservatory-trained musician would gravitate towards more predictable, conventional playing.

It’s a tough thing, because the classic music school story is that you attend school, you think you’re hot shit, you graduate, and then you realize how many incredible musicians and bands are out there and that you’re not that great, and that you have to actually work on your music beyond the training.

There are so many people that get stuck in the cycle of being super technically proficient and make overtly complex music that doesn’t really connect with anyone. You don’t have to use every aspect of your training in everything you play, and lot of educated musicians don’t seem to understand that.

The squealing guitar on “Multibeast TV” is wild. How’d you cop that sound?

That’s a DigiTech Whammy pedal with a little delay on top—a pretty standard effect for most guitarists these days. That was actually Peter’s idea. He suggested an over-the-top Whammy pedal and it worked out great. So I can’t take compositional credit for that part. I unfortunately can’t do that effect live because I have to play the funky guitar part that’s way more important to the song.

That super-low-to-super-high Whammy effect was used a few more times on the record—on “Eraser Stargazer Forever” and “Grass Shack.” It’s such a fun thing to play, but you can only do it so often before it becomes obvious that you’re gravitating towards it.

Is the funky, choppy guitar part on “Diamond Girls” an example of the atonal rhythmic thing you were talking about?

I remember specifically jamming on that song, and thinking out a funky, almost African groove, which is actually a little unnecessarily hard to play. It’s two stacked minor seconds on top of each other, which is a wide stretch to play, so it really stands out over everything else going on. The reason it sounds so weird is because the bass is playing in 4/4 over that part, but it locks in really well somehow even though they’re off kilter.

Guerilla Toss is rare in its ability to play around with time a lot, but retain a danceable pulse. Does the band focus on that when writing?

We used to be math-ier and much more technical about playing around with time. Personally, I’ve never really listened to math-rock, whatever that genre has become these days. It’s easy to get carried away with that shit—toying with time just for the sake of it. We’re getting more and more tasteful with those ideas these days.

Arian Shafiee’s Gear

Guitars1979 Kramer DMZ 2000

Fender Stratocaster (American-made)

Amps

Fender DeVille 4x10

Effects

DigiTech Whammy

Boss PS-2 Digital Pitch Shifter/Delay

MXR Carbon Copy Analog Delay

Fulltone OCD overdrive

Dunlop Cry Baby wah

Strings and Picks

D’Addario EXL115 strings (.011–.049)

Dunlop Jazz III picks

The tones on “Grass Shack” are some of my favorites on the album. What are you using there?

The little funky, two-note back-and-forth thing that I do in the verse? For that song I mostly use a straight tone, and, during a big cadence, I kick on the Whammy pedal and do a descending thing with it.

How do you play complicated parts while putting on your high-energy live show?

Our crowd is pretty energetic. I used to not have a pedalboard, but since I made one, for some reason having it onstage typically makes people less inclined to fall into you while you play and respect your space a little more. I used to sit down and play for almost two years of being in this band, but people would keep falling into me while I was playing, which is cool because they’re having their moment—but it obviously ruins the music. I do think our crowds are great because it’s always the line between respectful moshing and going truly crazy. It gets out-of-hand sometimes, but people always have fun and watch out for each other at our shows. They know what’s up. It’s not like a hardcore show, where it’s violent.

Did any gear play a particularly important role in the studio?

I kind of went in there with just my live gear, and a lot of the wild stuff that doesn’t sound like it comes from an instrument is Pete doing stuff, like overdubbing 20 congas and effecting them. But my guitar on the record is more-or-less how you’ll hear it live.

Do you have any philosophy on effects?

I’m sure plenty of interviewees say something along the lines of, “Well, I’m not really a gearhead,” but I’m truly not much of a gearhead. I come into pedals typically when they’re given to me, and when we did the records [2015’s Flood Dosed EP and 2013’s album Gay Disco] that came out on DFA, we got a little spending cash for pedals, and Peter basically bought me a bunch of stuff and said, “Here you go, we’re using this!” It was quite literally like being given a set of tools and being told to figure ’em out. But after shows, quite often, kids will come up and be like, “Dude! What effect were you using?” And the answer is almost always that it’s just a guitar through a really loud tube amp. It’s heartening, but also confusing for them. It’s all about blend for me. Get the guitar volume to the right level with just the right amount of gain on your amp, and it always sounds better to me than every pedal I’ve ever messed with. Maybe I’m a purist, but that’s how I work. You gotta limit yourself a bit these days. There’s just so much stuff.

In fact, I just finished recording an album of acoustic guitar that will be released in 2017. It was done as sort of a response to not wanting to do anything with gear, and just rolling up to a gig and not having to plug anything in or fight with gear. I hate it.