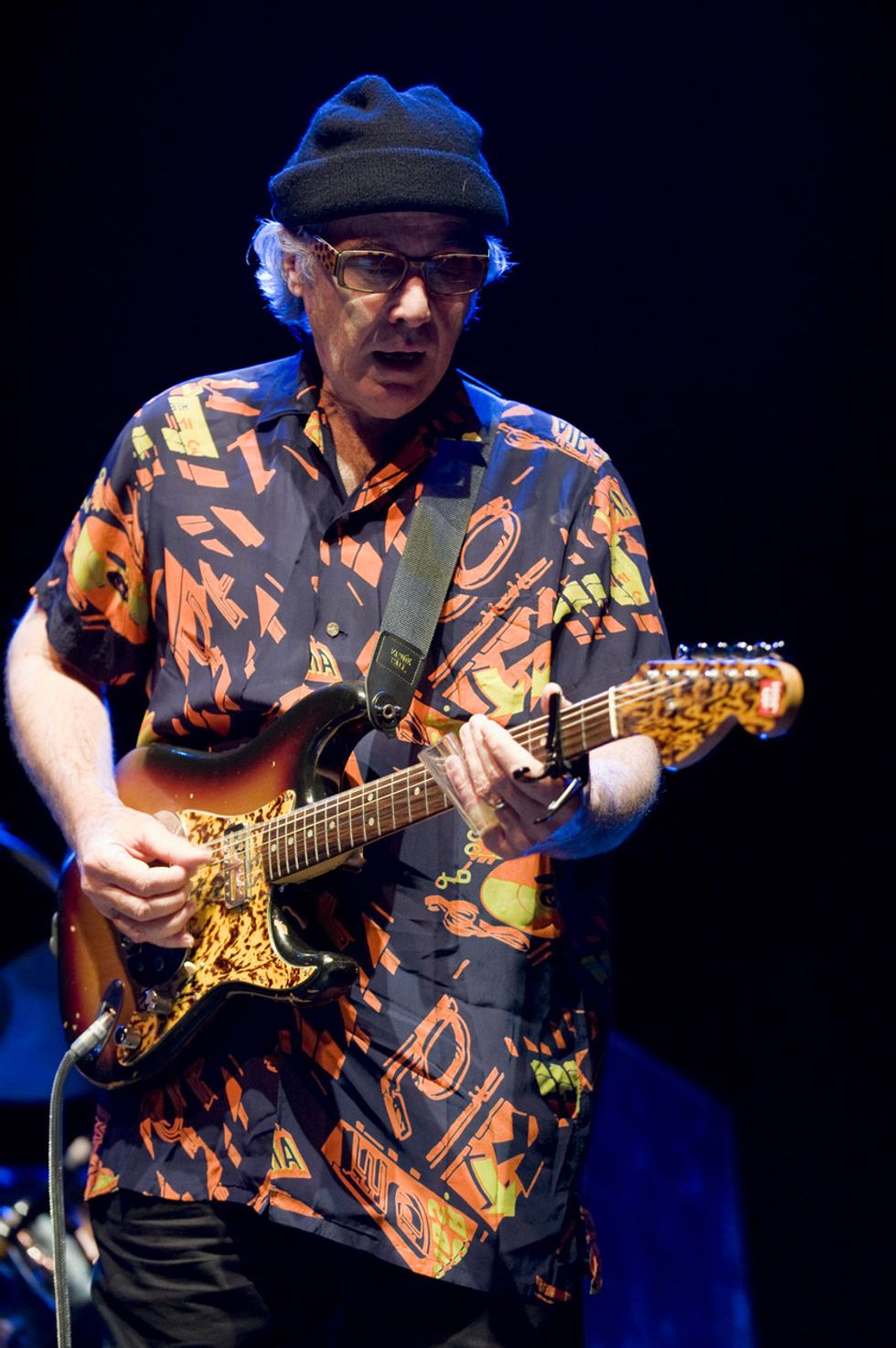

Ry Cooder is shown here in the studio with his son Joachim on drums during the making of Ry's new album, The Prodigal Son.

After more than 50 years of making music, Ry Cooder returns to his roots with The Prodigal Son, a trenchant spiritual quest that shows he’s still fascinated as ever by the deep mystery of how music connects us to one another.

Ry Cooder has never been the type to just sit on his hands and shut up. It comes through in his earliest solo work, from his 1970 rendition of Blind Alfred Reed's “How Can a Poor Man Stand Such Times and Live?" to his own three-album “California trilogy" of Chávez Ravine (2005), My Name Is Buddy (2007) and I, Flathead (2008): a restless and relentlessly incisive voice, always speaking truth to power, always aligned with the underdog. Not that Cooder is a political firebrand—far from it, in fact—but in the vein of one of his heroes, Woody Guthrie, he feels compelled to call out injustice when he sees it. And he sees a lot of it.

Of course, his approach to the guitar meshes with his personality: unhurried, unadorned, and unusually reverent of tradition, without being tethered to it. His technical prowess and expressiveness with the instrument is legendary, whether he's channeling the solitude and vast open spaces of Wim Wenders' film Paris, Texas or conversing with Malian guitar hero Ali Farka Toure on the 1994 classic Talking Timbuktu. Deeper still, his ability to capture and commit to a sound, especially in the bygone Afro-Cuban rhythms and melodies of Buena Vista Social Club, or in the modernized blues of John Lee Hooker's late-career resurgence-spurring Mr. Lucky, has positioned Cooder as a producer with a remarkably sharp ear for what works in service to a song.

That said, The Prodigal Son, Cooder's first solo outing since 2012's outspoken and agitated Election Special, is the work of an artist who's taking a hard look at the world around him, as well as a look back to the music of his eclectic Southern California upbringing. “When I was in high school," Cooder reminisces, “this country music radio station here in L.A. was sort of aimed at the defense plant workers that had come out to work in the aircraft factories. So at that time, you had Ray Price leading the pack with his honky-tonk band, which I was absolutely nuts about. The thing I lived for every day was to get home from school and turn the radio on, and then I'd sit there and wait for something to happen."

Along with Price, he discovered Wynn Stewart, one of the early proponents of what became the “Bakersfield sound" in country music. “If I'd have been really smart, I would've gotten on a bus to Bakersfield," Cooder says, “and gone to the Hub Café, where all these guys were playing. You could've seen them onstage. It would've been probably life-changing, as people say. I mean, I might not have come back!"

Lucky for us, he picked up a Martin guitar, eventually got his hands on a Fender Stratocaster (which he grabbed new off the rack at the Fender factory in 1967, just as he was heading into the studio with Captain Beefheart and His Magic Band for their seminal debut album Safe As Milk), and kept moving. Over the years, Cooder has developed a slide sound that has become instantly recognizable, in no small measure thanks to his famous “Coodercaster," a modified '60s Strat that he outfitted with a wider C-shaped neck and a Hawaiian lap-steel pickup near the bridge to reduce the level of “screech" that comes from using the glass slide on roundwound strings. (Cooder uses flatwound strings on his '67 Strat; he first made the switch to get a better bottleneck sound, but as the Coodercaster took over that role, he found that keeping flats on the Strat gave him a warmer, softer sound reminiscent of Curtis Mayfield.) He never uses a pick unless it's on his thumb, and his fingerpicking style, borrowed and built upon from years of listening to blues masters like Blind Willie Johnson (a prominent influence on The Prodigal Son), is so earthy you can almost feel the dust being kicked up when he plugs into a small vintage amp—a '50s Gretsch Artist among them.

TIDBIT: Ry Cooder's 16th studio album, The Prodigal Son, was recorded at engineer Martin Pradler's Wireland Studios and at Sage & Sound Recording in Hollywood. Cooder arranged a collection of strategic old-school gospel covers, mixed with a few originals, and he also played bass on most of the tracks.

Overall, The Prodigal Son is a triumph of intimate recording. Tracked with Cooder's son Joachim—now 39 and a trusted collaborator—on drums at engineer Martin Pradler's Wireland Studios and at Sage & Sound Recording in Hollywood, the album features ingeniuous covers of classics like the Pilgrim Travelers' gospel ode “Straight Street," Blind Alfred Reed's haunting “You Must Unload," and the Stanley Brothers' soulful bluegrass anthem “Harbor of Love," as well as Cooder's arrangements of Johnson's “Nobody's Fault But Mine" and the title cut.

Comprised largely of first and second takes, with Cooder even playing bass on most of the songs, the album is pristinely mixed, and yet it projects an edgy but controlled rawness—a bluesy and distinctly American wail—that has come to signify Cooder's timeless guitar sound. On his own song “Shrinking Man," for example—a dry, Dylan-esque send-up on growing old and searching for hope in a heartless society—Cooder wrenches a perfectly jangly tone from a vintage Kent Electric Mandola that helps define the character of the song.

“Recording is a funny thing," Cooder notes, “because nobody will teach you this. It's just not taught. It's not like somebody sat me down and explained everything about microphones and wires and gain structure and what happens in the studio. I had to learn by doing, and I was lucky to be able to learn it. I mean, it's taken me a lifetime, but I'm always messing with stuff, and I have to say, at age 71, thankfully, I feel like I'm there, you know?"

The Prodigal Son seems to point specifically to a coming back home to something deep and essential. Is that how making this album felt for you?

Oh, it's hard to say how you feel when you make an album. I mean, each tune is a little problem to solve, so it's an experiment every time, I guess, although I have to say after having done this for 50-odd years, I'm a little more certain that I know what's going to happen. It's not like being in the dark all the time, like I used to think. I was always puzzled.

But after all this time, I have Joachim with me now, so there's a degree of certainty there because he's a good colleague. That makes a lot of difference. We get a little idea, we try it, and if it's good then we go on to the next one. When it's done and you look it over, then you say, “Oh I see, this is about the Prodigal Son, so it's some kind of quest. For what? [Laughs.] What do these tunes suggest?" To me, empathy and sympathy among people. Why? Because it's hard to find. It's like Buddy the red cat [from My Name Is Buddy] searching for solidarity. It's the same thing really—Buddy was the prodigal son, after all. What was he looking for? He was looking for fellow feeling. So in this case, we say simply let's be empathetic and let's be sympathetic to one another. Treat a stranger right, as Blind Willie Johnson says.

Along those lines, you draw on a wealth of influences with the songs you chose to interpret—some of them familiar, like Blind Willie Johnson (“Nobody's Fault But Mine"), and then others maybe less so, like Blind Roosevelt Graves (“I'll Be Rested When the Roll Is Called") and William L. Dawson (“In His Care"). How did you go about choosing them?

Well, I knew those tunes. Roosevelt Graves, I've known that song for a long time. I don't really know who he was. He seems to be one of these peripheral characters, and he recorded with his brother, who was not even named, so it's always “Blind Roosevelt Graves and brother," which is funny. It's kind of mysterious, but I love that song. That's my best shot at sounding like Roosevelt Graves—who's really good. He didn't do just gospel, either. He did secular tunes and comic songs, and he sounds almost like a minstrel player—kind of like Emmett Miller. But who knows who some of these people are?

I had a Folkways 10" of “In His Care" [performed by Sonny Terry & Brownie McGhee] when I was pretty young. It was probably the first gospel song I ever heard, and I loved it. It was really stomping, and I thought, “Man, that is good. That's the kind of thing I like." Nobody said to me, that's gospel music. I didn't know what the song was about. I knew it had something to do with the Bible, but I didn't grow up in a church-going area. In Santa Monica, you don't really encounter that. The records were it. They were like this portal, you see, to another world. That's why I liked them.

Cooder's main slide guitar is his '60s Coodercaster, which has an early '60s Teisco neck pickup given to him by David Lindley, and a Valco lap-steel pickup in the bridge. Photo by Jordi Vidal

So did you set these records to the side hoping to record versions of them one day, or did your choices come together more organically as you started work on the album?

I think it just came together. Over time, I had recorded some gospel music, but to do a whole record, I never would've considered it until Joachim and I went out on tour with Ricky Skaggs and the White family. We prepared for about a year, and then toured for about a year, and we did a lot of gospel music—all country gospel. And I actually had the best time of my life. I never had such fun, because I was afraid that I was getting older, I was going to miss out. And I wanted to do it. As a teenager in high school, I used to think, “I'll be like J.D. Crowe. I'll just play banjo, and I'll be in one of these bluegrass bands, and I'll sing all this music, and that will be the way I'll live." Of course, it didn't happen—anything but. But then time goes by, and you think, “This is what I wish I could do." So we finally did it, in a way.

I would say to Ricky and the Whites, “Are you sure you want me singing this? I don't come out of this tradition, so what do you think?" “Oh, no," they said, “you just keep doing it. It's good." Then we'd do some shows, and I'd go, “Well, I don't know. I'm not nailing this Lester Flatt voice at all." “Oh, no, you keep doing it." So by the end of the year, I thought well dang it, if they think so, then I think so. Let's look into this. But we needed to find our own way of doing it that wasn't the straight traditional way, because that's just too hard.

Did you and Joachim talk about all this before you went in the studio?

No, we don't talk [laughs]. How it works is, I needed some kind of method of how to think about these things, rather than just, “Jesus, do I have to sit here and bang everything out of nothing?" It's too much work. Joachim had all these tracks that he made, very ambient and very pretty, and some of which involve sampling bits and pieces of my old stuff. They're nice little ideas that he comes up with, plus these array instruments that he plays—they're like orchestral mbiras that are finely tuned, very ethereal and very large. You can find videos of him playing them. It's pretty fascinating.

So he played me these tracks and I said, “You know, I think I can convert that into 'Straight Street,' or I can make 'Harbor of Love' out of that." Then I'd play and sing over the top, and work on them a bit. The decisions had already been made about tempos and keys, you know? I don't have to carve everything out of a block of wood.

Ry Cooder's Gear

Guitars

'60s Fender “Coodercaster" modded with an early '60s Teisco pickup (neck) and a Valco lap-steel pickup (bridge)

'67 Fender daphne blue Stratocaster, modded with a Guyatone pickup (neck) and a Bigsby steel-guitar pickup (bridge), with a Bigsby tremolo

1959 Gretsch 6122 Country Gentleman

Japanese Kent Electric Mandola

1960 Martin D-18 (formerly owned by guitarist and gospel singer Ralph Trotto)

'70s Ventura “Lawsuit" Jazz bass

Amps

Fender Tweed Deluxe

Fender Vibroverb

'56 Fender Super

'50s Gretsch Artist

The “Green Man" (dual tube guitar preamp designed by Danny McKinney)

Strings

D'Addario EXL115W Nickel Wound Medium (.011–.049, on the Coodercaster)

D'Addario ECG25 Chromes Flatwound Light (.012–.052, on the daphne blue Strat)

And then some of these we played live in the studio. “Shrinking Man" is straight from the floor, with the guys [Terry Evans, Arnold McCuller, and Bobby King] singing with me. “I'll Be Rested" is done that way—which is fun too, because that's real dynamic. You sit there and you bang it out. That's nice to do when the song is simple enough, and you know exactly how you're going to do it. But if you have to find it, these other methods help you get there. “Gentrification" was a track that [Joachim] had. I simply played guitar and sang over it. It was a funny track, and I thought the lyrics were funny, so I made up a tune out of it.

Was there a basic setup that you relied on to record your guitar, or did that change?

Well no, it's always the same. What I have here in terms of equipment, some people have asked me about this thing I call Green Man. It's a little device that looks like a Variac [variable transformer], but it's a stereo conversion thing. So the guitar goes in mono, and comes out stereo, with tubes and transformers jammed up inside it—it's like something NASA made. It has phase correction in it, too. But on top is this great big volume knob, so if a guitar is low power, let's say, you can turn it up. If your guitar is too hot, you can turn it down. So you have a lot of control over the game.

Then that goes into two amps, and the trick is to find two that sound good together. And not just two amps, but a setup that gives you a summing kind of effect. Suddenly there's an expansion, a harmonic richness that you can get, but you have to have the right combination, and then it can't be too loud for the room. So I use little amps—they're pretty small, but they sound good this way. On “Shrinking Man," for example, I used a tiny little Gretsch Artist and a '56 Fender Super that gives you a real nice, almost hi-fi sound.

But the Green Man is the answer to everybody's prayer. I used to have a hell of a time with amps and electric guitars, because they were always so strident and brittle and loud. There was always that one speaker blasting away and yelling at me! I couldn't stand it, and then finally, Danny McKinney, who's a friend—he makes the retro Standel amps—I told him, “This is what I need. Can you do that?" He says, “Oh, sure." So he made this thing, and it's the answer. I use it onstage, I use it when I'm at home, I use it in the studio, and it's an incredible device. To get a big sound, and spread it out so it's not so pointy and not so goddamn insistent—it just sort of fills the space up and you can really deal with these low-power guitars that have a sweet sound, like say a Premier or a funny old Teisco. Nobody had ever heard the richness of these instruments before, because they always play them through an amp that's hitting you over the head. Now, I get this harmonic content coming out of these funny old electric guitars. That finally opened it all up for me.

In “The Prodigal Son," you reference Bakersfield and pay tribute to Ralph Mooney, not just in the lyrics but in the slide parts and leads you're playing. How has Ralph's music influenced you?

Well, “You Took Her Off My Hands," that was Wynn Stewart's first big record, and the steel guitar enters this thing and I thought, “What is that?" Somebody told me, “That's pedal steel," and I thought, “I'd like to know about that," but you can't just walk into it. Somebody has to show you, and it's not like guitar. It's hard.

One of the greatest sounds is Ralph Mooney on that Fender 1000, because those string pulls are so fast, it enabled him to make these chord dips that were real syncopated because he had that pedal action. It's different from a Sho-Bud or a Bigsby steel, which is more gradual—a little more languid, I suppose. A steel player friend of mine, Steve Fishell, explained all this to me. The pulley action on the Fender 1000 is real abrupt, so he could make those things happen. And the way they recorded up there in Bakersfield, if that's where they did it, it was pretty stripped down out to where you heard everything. It wasn't mixed back with a lot of echo.

So I liked that very much, and I still do. In fact, I love it so much, I was doing “The Prodigal Son," which only has two verses, and Joachim says, “It's too short. What are you going to do?" How do you rewrite a tune like that? Then Martin says, “Well, he leaves and then he comes back. So what happened in the meantime?" It was like a story conference for a movie [laughs].

So I just made up this whole business about how I wandered into a tavern where a band was playing. It's like this hobo holy man looking for something. “Is this a new teaching?" and the waitress says, “Yeah, as a matter of fact." And that's faith. He found faith. The old Bible story says he found God. Well in this case, he found Ralph, which I think is funny, and it's also quite realistic. I mean, you might be converted! I'm sure that if I had gone to Bakersfield in 1960 and heard these guys, I never would've left, and I probably wouldn't be talking to you right now.

There are a few layered guitars on your song “Gentrification." How do you go about making parts like these fit together?

I have this mandolin-ish, long-neck electric that's real twangy, with thin strings that make it sound like a harp. I started off with that, just to have something quiet so I didn't have to sing against the amps. Also I didn't want to cover up this funny track of Joachim's that's just him playing this array of actual nails that are tuned. You use resin on your fingertips, and you kind of bow them to get that whistling sound. We wanted to make sure that's heard because that's what gives the track a sense of humor. So I just played this mando and kept it down low in the mix.

Once I'd sung it, I put two guitar parts on it that are sort of answering one another, like squirrels running after each other, just to provide some chord movement. So you're hearing these two parts with the capo way up high, really screechy and good, almost like a keyboard. Then Martin did some processing on it and contained it in a nice way, so it's not too big. That's a question of balance, which, of course, is what recording is all about.

You've talked about how there's a mood of reverence that takes hold when you play and sing these songs. That sounds like an exalted state.

[Laughs.] You may be right! But to instill reverence on the one hand is to say you're being aware of everything. Your awareness is up rather than down. Your feeling for things is in tune, rather than out-of-sync with everything. In other words, be part of the world. Be in on things, and be in tune with things. That's what a musician is supposed to do, and I like that very much. I had not thought of the word reverence that way, and I credit my granddaughter's nursery school teacher with the idea. She's Kashmiri and Islamic, very sweet and very quiet, and she sings everything, because that's of course an easier way to get people to pay attention. It's not a command. It's an encouragement.

Another word for reverence is empathy, which is also what I feel these songs hopefully are about. It's so we don't feel isolated and cut off from other people. We include them, so they don't feel marginalized. So when Jesus says, “I like sinners better than fascists any day"…. I don't know if people are going to take it this way, or how they'll read it, but that's the intention. It wasn't clear to me until I finished the record, but it's a good idea anyway, you know?

YouTube It

Ry Cooder explains the gospel and roots connections that inspired his new album, The Prodigal Son, in this mini-documentary.

- Cult Coils: Lesser-Known Vintage Pickups | Premier Guitar ›

- Ry Cooder ›

- Deep Cuts: Ry Cooder's Funky Fingerstyle | 2014-08-21 | Premier ... ›

- Cristina Vane on Blind Willie Johnson's "Jesus Make Up My Dying Bed" - Premier Guitar ›

- Taj Mahal and Ry Cooder Reunite for New Album Get on Board - Premier Guitar ›

- Guitar Player Makes His Own Ry Cooder Fender Coodercaster - Premier Guitar ›