Shapes of Things: A Brief History of the Peculiar Behind-the-Scenes War Over Guitar Designs

Left: A 1959 Les Paul Standard owned by John Clardy. Photo by Billy Mitchell taken from Electric Guitars & Basses: A Photographic History by George Gruhn and Walter Carter, © Gruhn Guitars, used by permission. Right: A PRS SC 245. Photo courtesy of PRS Guitars.

A brief history of the peculiar behind-the-scenes war over guitar designs.

For the previous 50 years, Fender had taken a mostly permissive attitude toward guitars built in the Tele or Strat style. Of course, they fought outright counterfeits, but as any perusal of guitar magazines from the '70s and '80s will attest, scores of makers were offering Strat and Tele doppelgangers—and there seemed to have been few cease-and-desist letters, few lawsuits. Why, Bienstock wondered, would Fender suddenly be seeking trademarks for the body shapes? He foresaw trouble for artisans like Tom Anderson Guitarworks or Roger Sadowsky of Brooklyn, whose S-style and T-style guitars pay homage to the Strat and Tele, respectively, only with a master luthier's touch.

Trademarking those shapes "would have turned the entire guitar industry on its head," the bass-playing lawyer says. "You have companies that have been making guitars and basses in those shapes since the late '50s. There was a visceral reaction." The worst-case scenario: a future in which Fender could shut down models some builders had been making for 25 years or insist on licensing fees. "None of these companies were saying these are shapes that they own," Bienstock adds. "They were just saying they are shapes [Fender] can't stop me from making."

So Bienstock, who has a long history of working on such cases, moved to block Fender's hoped-for trademarks on behalf of a consortium of independent guitar builders. Thus began one of the more contentious cases involving guitars and the courts in recent years—the latest flare-up in the guitar universe's strange, decades-long battle over body snatching. The decision came down last year (more on that later), and some say it marked the final word on guitar mimicry. But litigation is forever, so one never knows.

Trademarks vs. Patents

Guitar copies and the legal wrangling around them is one of those subjects that guitar aficionados talk about from time to time with more fascination than information. There is no clear body of law defining how far one may go in copying a design without exposing oneself to a lawsuit. There's no telling when or how you'd get sued, because the originators of the iconic guitar designs have historically been inconsistent—even arbitrary—about when and how aggressively they've challenged clones.

At a time when the music industry is obsessed with copyrights and intellectual property, the guitar industry operates in an environment somewhat like the permissive shadow world of hip-hop mix tapes. For most of the past 50 years, the guitar market has largely been a free-for-all where guitar manufacturers—from individual luthiers to assembly-line operations— have imitated classic guitars almost at will. In some cases, builders improved on the iconic designs and charged premium prices. In others, companies of dubious repute mass-manufactured mediocre facsimiles and sold them to players who covet the real thing but can't afford it. Of course Fender and Gibson, the two guitar makers with the most at stake, have introduced their own entry-level versions of their key models, but one could ask reasonably why should they have to compete with other makers' knockoffs of their own designs?

To get a handle on this issue, we'll need to go to law school for one paragraph so we can learn the difference between patents and trademarks. (In case you're wondering where "copyright" fits into the equation, it applies only to composed or authored works and, therefore, has no bearing on guitars or other manufactured items.) Patents cover inventions—anything that is functional, as opposed to aesthetic. One has to apply for a patent through a rigorous process in which you prove originality and describe your design in detail. If you win a patent, you have exclusive rights to make or license the invention until the patent expires (these days, it lasts 20 years). Trademarks, on the other hand, cover brands and nonfunctional design features (like Nike's swoosh or Fender's logo and signature headstock shape). Trademarks never expire. However, trademark owners must consistently protect and defend their trademarks. So for example, Xerox couldn't be lazy for 20 years and let other companies claim they make a better "Xerox" machine and then suddenly swoop in after the term has become generic and sue folks for using it.

Clash of the Titans, Pt. 1

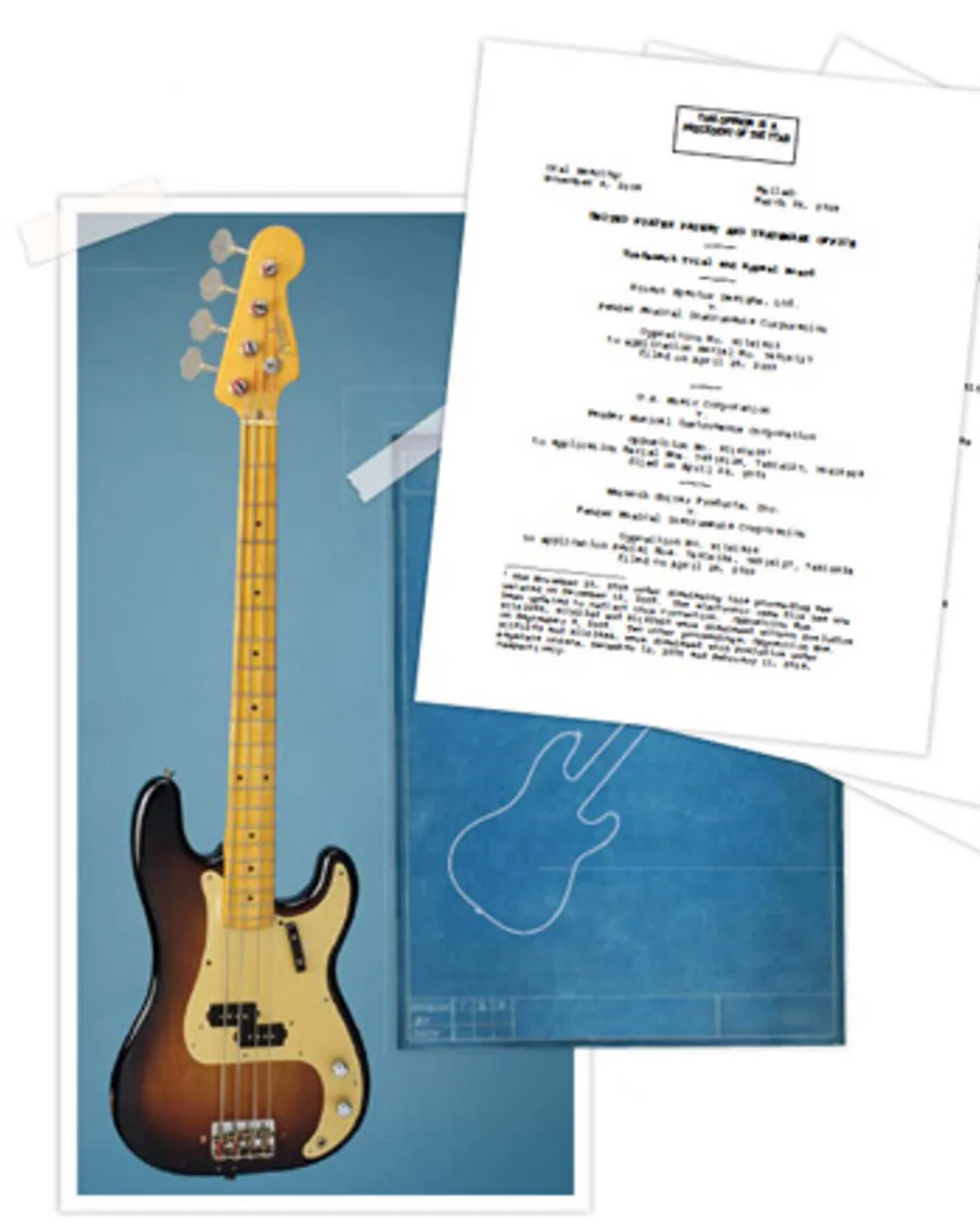

A 1959 P bass owned by Clifford Antone. Photo by Billy Mitchell taken from Electric Guitars & Basses: A Photographic History by George Gruhn and Walter Carter, © Gruhn Guitars, used by permission.

The earliest industry trademark dispute anyone seems aware of actually pitted Fender against Gibson in the mid 1960s. Gibson had engaged automobile designer Roy Dietrich to come up with the Firebird, a zig-zaggy electric guitar that some have said evoked the era's oversized automobile tailfins. Fender decided that it too closely resembled its Jazzmaster and either sued or threatened to sue. By today's standards, Gibson would have had a pretty easy time defending itself—the profiles of the two instruments are quite different. Nonetheless, Gibson voluntarily made dramatic changes to the Firebird design and the dispute became moot.

Fast-forward to the 1970s and the rise of the Japanese manufacturing juggernaut. Besides small, fuel-efficient cars, the Japanese were making ever-better musical instruments. One such company was Hoshino Gakki, maker of Ibanez guitars. During that time, Hoshino made several lines of instruments that were clearly meant to evoke, if not outright copy, the look and sound of Gibson Les Paul and ES series guitars. According to a history of Ibanez by Michael Wright, Gibson's parent company at the time (Norlin) filed suit in Federal District Court in June of 1977 against the US distributor of Hoshino instruments "to send a message to all companies making copies" of Gibson instruments. The suit wasn't aimed at cloned body styling per se, but at overly similar headstock designs, which have always had more weight in the guitar world's code of honor than body styling anyway.

Wright says Hoshino had been preparing internally for such a challenge from US makers for several years and that Ibanez was moving away from copies to unique designs anyway. So the suit was easily settled out of court when Elger, the US distributor, pledged to stop making any evocative headstocks or using any confusing branding. Despite the lack of legal bloodshed, today you can find so-called "lawsuit" Ibanez guitars with Gibsonlike headstocks from the mid-'70s fetching anywhere from nearly a thousand dollars to more than two grand.

Clash of the Titans, Pt. 2

More recently, Gibson made a major trademark move on our own shores by suing Paul Reed Smith Guitars, one of the most esteemed craft builders in the country. Filed in November of 2000, the suit claimed PRS Singlecut solid-bodies infringed on Gibson's trademark of the Les Paul body shape, a trademark it had secured seven years prior. It was a sweeping, aggressive claim that demanded massive damages and accused PRS of unfair competition, fraud, and deceptive business practices. It seemed almost surreal, especially since a variety of companies around the world had been making far more accurate facsimiles of Les Pauls for years. Nevertheless, in 2004 a district court ordered PRS to stop making, distributing, and selling the Singlecut—one of its best-selling guitars.

The ban lasted just about a year. Then the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals overturned the injunction and in every possible way rebuked the findings of the lower court. One key part of the ruling hinged on one of the core criteria by which trademark infringement is tested—the likelihood that a consumer will be confused into purchasing an imitator brand while thinking he's buying the original. In assessing whether PRS Singlecuts passed this particular test, the appeals court cited the testimony of guitar historian Walter Carter, an expert witness called by Gibson, who famously said in a deposition (much to Gibson's dismay) that even if there were a possibility that someone could mistake a Singlecut for a Les Paul at a distance or in a smoky bar, "only an idiot" would confuse one for the other at the point of sale. Given that the PRS Singlecut had been such a hot seller before the court battle, it comes as no surprise that the company launched back into production of the single-cutaway guitar designs immediately after the court ruling. Current PRS guitars with that shape now include several SE import versions, US-made signature guitars such as the Mark Tremonti model, and the new US-made SC 58.

Carter, who works for Gruhn Guitars in Nashville, says the confusion test is too vague to be worth much anyway. "First, you've got to know enough about guitars to be even able to confuse the two," he says. "If you don't know anything about automobiles at all, you're not going to confuse a Volkswagen with a Cadillac. And then you can't have too much knowledge, or you won't be fooled for more than a second."

In the end, while Gibson failed to prove that PRS had violated its trademark, Gibson retained the trademark itself. So nothing rules out the prospect that the company could go after makers of more convincing Les Paul copies in the future.

Back to the Future (2003, That Is)

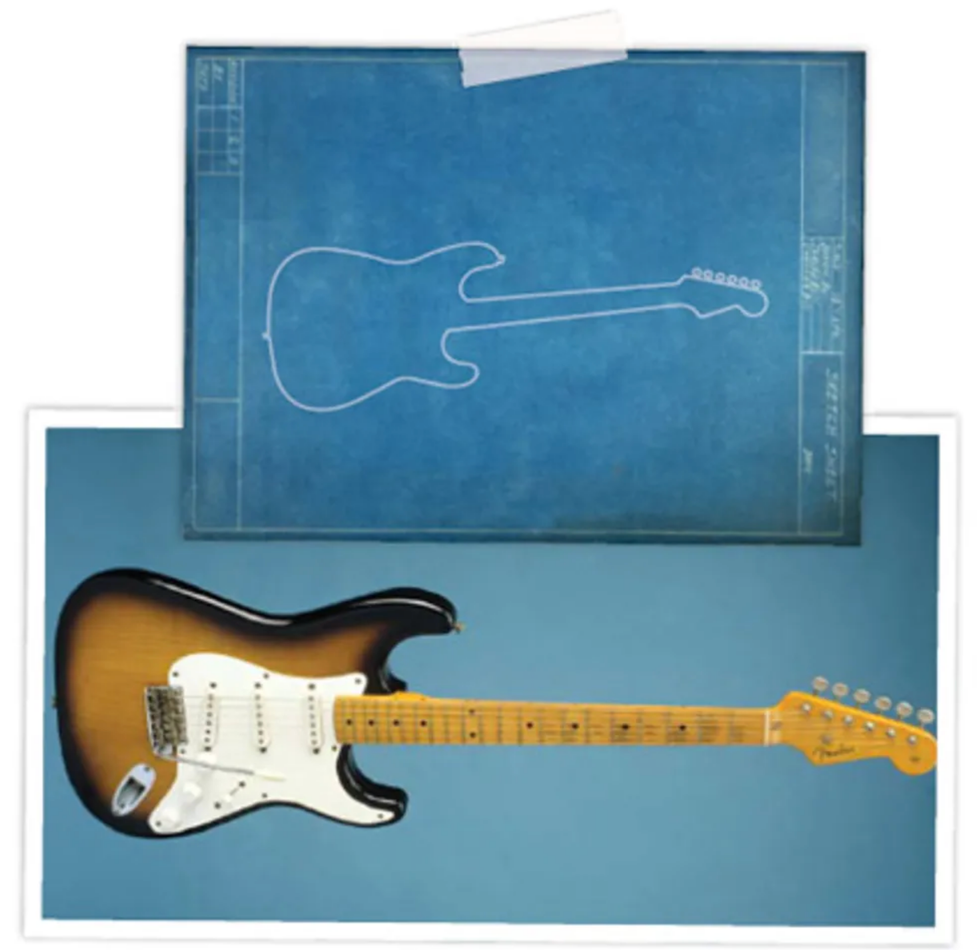

A 1954 Strat owned by Clifford Antone. Photo by Billy Mitchell taken from Electric Guitars & Basses: A Photographic History by George Gruhn and Walter Carter, © Gruhn Guitars, used by permission.

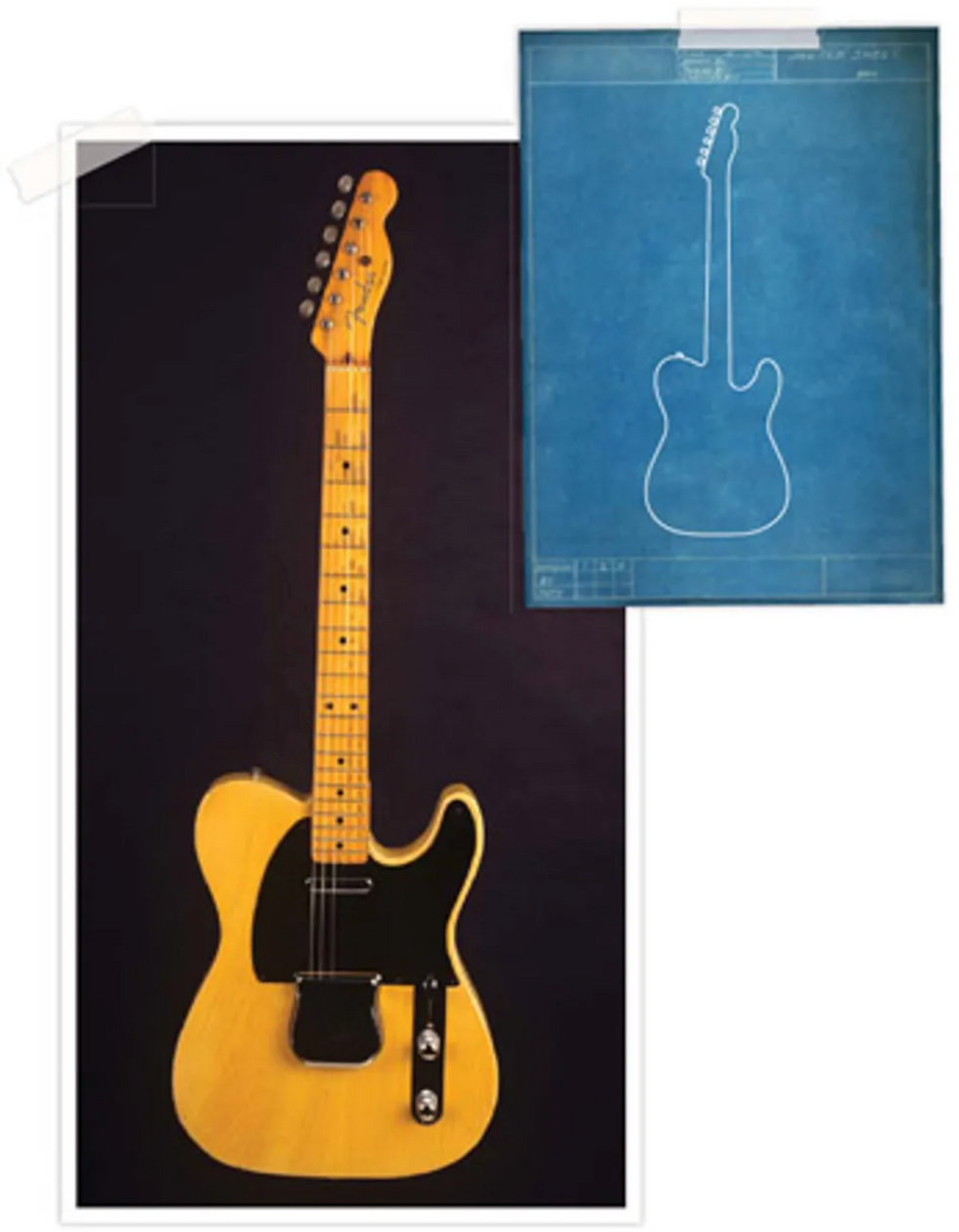

The case pitting Fender against Ron Bienstock's consortium of guitar builders was different. While Gibson had been trying to defend a trademark it already owned, Fender was applying for trademarks it had never had before. The obvious question was, after five decades of making Teles, Strats, and P basses, why then? The company's chief legal officer Mark Van Vleet says it was a response to a growing threat to the integrity of Fender's designs. "With the advent of the internet and with manufacturing in China being so prevalent, our primary concern was trying to deal with counterfeits and infringements—companies and people who are clearly trying to ride on Fender's history, Fender's place in the industry, and Fender's iconic status to sell their goods by confusing consumers." Van Vleet also says Ron Bienstock was being premature and speculative in his assertions that Fender was going to use its new trademark to muscle in on small luthiers.

"Our position is not that we were trying to monopolize anything," says Van Vleet. "We simply believed that we had the rights to these designs and, therefore, were trying to obtain rights that we were entitled to, just like we have in the past and like many other companies in the industry have done. We certainly were not trying to do something to the disadvantage of the industry."

Nevertheless, Fender fought for six years before the United States Patent and Trademark Office's Trademark Trial and Appeal Board (TTAB) rendered its final decision in March 2009. The trademarks were denied. Quite simply, the TTAB said, the claim came too late in the history of guitar building: Fender, they concluded, "never policed the body shape, only the word marks and headstock profiles. In addition, they never claimed trademark rights in the body outlines publicly through, for example, the catalogues, until 2004. In the meantime, many other guitar manufacturers sold guitars with the identical body shapes for at least 30 years, either as complete guitars or in the form of kits. In view of the above, we find that opposers have proven their claim that the applied-for configurations are generic."

Fender's Van Vleet says the company "respectfully disagrees" with the ruling. "In our opinion, the issue before the court was whether or not consumers or prospective consumers associate Fender being the source of those two-dimensional shapes. And we had boxes and boxes and roomfuls of evidence indicating that, when consumers saw those designs, they associated Fender as being the source." Van Vleet won't specify any actions the company is currently involved in against guitar makers for other trademarks they do own, only that, in general, "We will go after companies who we believe are infringing—somebody who's trying to confuse the consumer out there between what they're doing and what we're doing."

The Right Stuff

Victorious attorney Bienstock spins last year's decision on the Fender case as an important ruling on behalf of creative lutherie. "I fully believed in the righteousness of the cause," he says. "We needed to have this result. This was the right thing."

But it still doesn't seem that clear-cut. When it comes to building upon other companies' or individuals' designs, luthiers are still bound to ask "What's safe, legally?" Writer types are raised to believe plagiarism is pretty close to the worst nonviolent offense on the books. But guitar building is an art as much as it is a business. And art allows for—indeed depends on—creative borrowing and license. So the question then becomes whether one can bring an artist's eye to a copy. Is making your own "Strat" like covering a great song—that is, is it more of an homage—or is it a selfish move more akin to ripping an album you didn't buy and serving it on BitTorrent?

Gruhn Guitars' Walter Carter, who sees luthier-made tributes to Strats and Teles come through the famous Nashville shop all the time, says honorable builders "try to make some kind of improvement, cosmetic or functional— whether it's a beautiful top or a different kind of contour . . . almost always a different headstock . . . different pickups. That's the line between integrity and copy."

A 1953 Tele owned by Toby Ruckert. Photo by Walter Carter taken from Electric Guitars &

Basses: A Photographic History by George Gruhn and Walter Carter, © Gruhn Guitars,

used by permission.

Guitar historian and journalist Tom Wheeler agrees. "There are plenty of guitars out there made by reputable [builders] that one could look at and say, 'This is an interpretation of the Strat idea.' I think that's fine. I admire those guys. It's the guitar that is a copy down to the last screw that I feel it's a shame that Fender gets nothing." Wheeler shares other luthiers' puzzlement that these infrequent-but-intense battles have been fought over something as generic as the mere body shape—without reference to all the key design elements that make up the "face" of a Strat or Tele. "I hope that, at some point in the future, we can get beyond the issue of the two-dimensional body outline so that all manufacturers and every creative person can be a little more protected in their creativity and their work."

The Irresistible Piñata

It's been about a year since the Fender trademarks were denied, and with no conspicuous lawsuits out there, the few guitar geeks who watch this issue closely are saying it's probably now pretty much over. If you can't win a claim on a trademarked shape you do have (like Gibson), and you can't gain a new trademark on a tried-and-true body style (Fender), then where else is there to go? All we're left with is a fascinating question for the Monday morning quarterback. Did Gibson and Fender blow a historic opportunity and forego millions of dollars of revenue by not protecting their signature body shapes through trademark law earlier and more often?

James Boyle, a professor at Duke University who specializes in intellectual property issues, says there is no clear answer, because one has to remember that all those copies over the years have in a sense served as free advertising for the real thing. Boyle, reached by email, examined the issue in proper professorial fashion—in the form of some good questions: "Is part of the reason that Les Pauls, Strats, and Telecasters are iconic because they were the subject of so much slavish copying? Did the copying end up establishing them as the undoubted aristocracy of the guitarists' world—the guitar that the junior rocker dreams of moving up to once he has graduated from his first cheap knockoff? Or did [other manufacturers' copies] lose them a market that they could have legitimately controlled with trademark, and thus represent a substantial number of lost sales or licensing payments? You and I might have intuitions about which course would have been best, but it is hard to claim a watertight economic case."

No doubt the chief executives of those companies wonder about this themselves—perhaps more often than they let on. And, considering the sporadic history of this fight—as well as the stakes involved in such a competitive economy—it seems probable they or some future executives will eventually take another swing at the piñata.

[Updated 11/1/2021]

- Ibanez "Lawsuit Era" Les Paul Custom Copy - Premier Guitar ›

- Dimebag's Dean of Destiny - Premier Guitar ›

- ESP James Hetfield Snakebyte Electric Guitar Review - Premier Guitar ›