Chops: Intermediate Theory: Beginner Lesson Overview: • Understand the essential elements of Chicago blues. • Learn how to properly back up a harmonica player. • Create “looping” phrases that

Chops: Intermediate

Theory: Beginner

Lesson Overview:

• Understand the essential elements

of Chicago blues.

• Learn how to properly back

up a harmonica player.

• Create “looping” phrases that

build tension in your solos.

I’m back to help you expand your blues vocabulary further, this time with some chords, partial chords, and chord voicings that you have to know if you’re going to play lowdown Chicago-style blues right.

In the classic Chicago blues styles of the ’50s and ’60s, rhythm guitar and lead guitar melded together in a unique and intricate way. So in these examples, we’ll expand your lead playing as well as your rhythm chops. In the classic bands of the era, such as the groups led by Muddy Waters, Little Walter, and Sonny Boy Williamson II, the harmonica was as much—or even more—of a dominant lead instrument as the guitar.

Many bands featured two guitars, like Robert Jr. Lockwood and Luther Tucker with Sonny Boy, Dave and Louis Myers with Little Walter, and Jimmy Rogers or Pat Hare together with Muddy in his band. Here’s what’s neat about everything I’m about to show you: When you turn up for your solo, all these chords and licks are great lead tools as well. Just listen to SRV soloing over any of his shuffles and you’ll find traces of all this stuff.

The ensemble playing of the bands I’m talking about was very much a team sport. The guitar parts, harp parts, and piano parts could often be solos in their own right, but the players knew how to blend together to make one sound. Therefore, the first step is to turn down your rhythm.

You may say, “Hey, I do turn my rhythm guitar down.” No, you don’t. Not enough!

Blast your solo as loud as you want, but keep your rhythm guitar volume to a minimum. Always keep in mind that playing accompaniment too loud will not have the effect you may think, no one will be impressed, they’ll just want to hurt you and for you to go away. That’s enough philosophy— let’s get down to some nuts and bolts, tricks and licks.

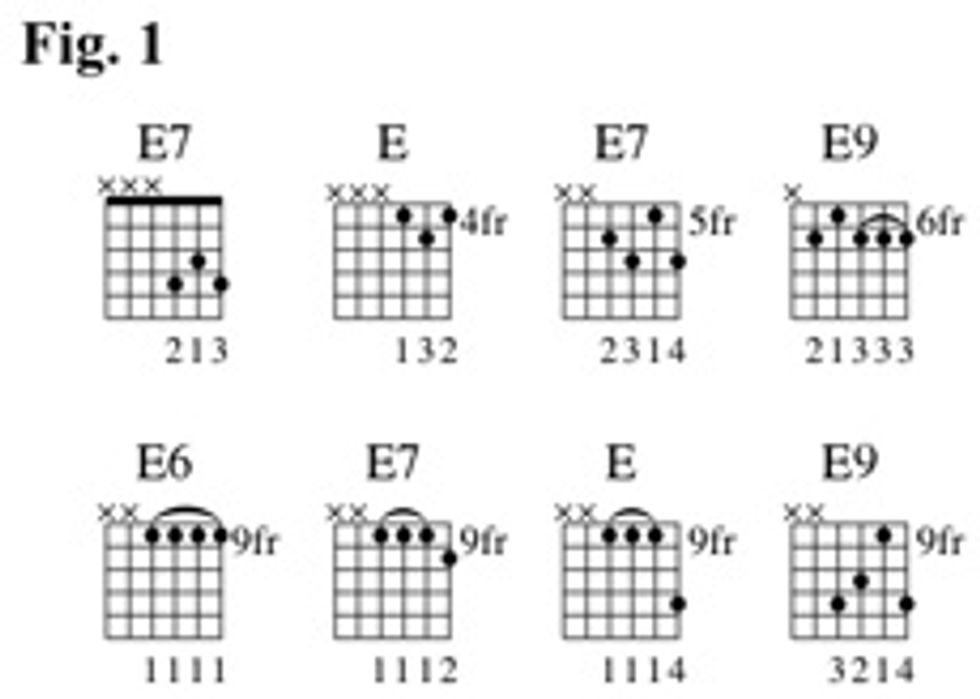

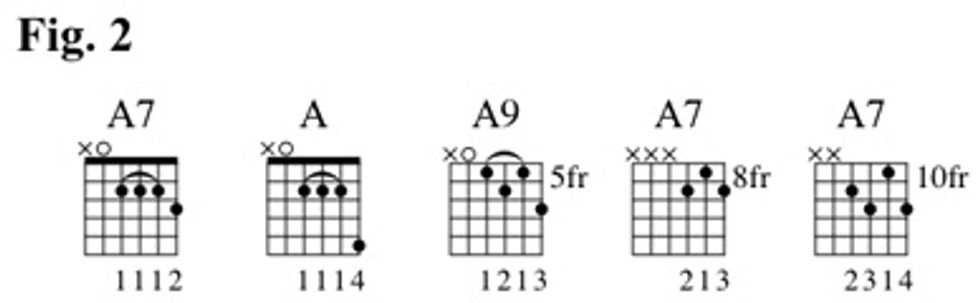

We will begin by checking out the common chord shapes used during this era. In Fig. 1 you can see a few options for E and in Fig. 2 we do the same for A. Now we have the I and IV chords for a blues in the key of E. For the V chord just take any of the “A” shapes and move it up two frets. It’s magic!

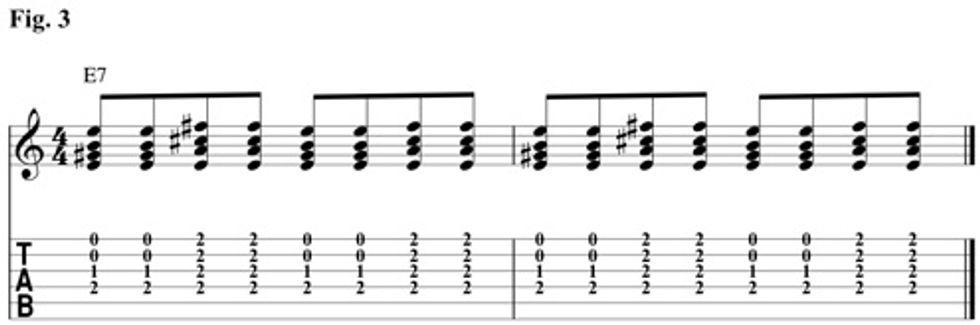

Let’s start with a dirty shuffle rhythm using our basic open E chord and an inversion of a E6/9 chord in Fig. 3. We can use our new superpowers to simply move this shape up to the 5th and 7th frets for the IV and V chords, respectively.

Robert Jr. Lockwood was really the originator of most of this stuff I’m showing you. Both Lockwood and the sadly under-documented guitarist Reggie Boyd were pretty much the most well-rounded, virtuosic, and most knowledgeable players of the era, and many bluesmen of the time got a lesson, directly or indirectly, from these two guys.

Now that you have the basic chord shapes, it’s time for some licks. I know how much you all like licks, but bear in mind the words of the great American bluesman Sonny Lane, “F**k a lick!” What I choose to believe he meant was don’t make up your mind about what to play until you are in sync with what’s going on around you musically. Use your ears, not your licks! The lick in Fig. 4 is a great way to segue from the I chord into the IV. For some extra vibe, add a slight palm mute and use all downstrokes.

I call the lick in Fig. 5 a “looper.” Once you get it going, you can pretty much go on autopilot for a while to build up tension. In the example, I have outlined how to play this phrase over the I (E7), IV (A7), and V (B7) chords in the key of E.

We have another looper in Fig. 6, and this time we will use it over an A7. The addition of the 9 (B) at the top of each phrase is a Lockwood staple, revealing that he could be somewhat more sophisticated than his surroundings."

Everything I’ve shown you here is not only great for big, powerful solos, but I have also started you on the path to learning how to correctly accompany a Chicago blues harmonica in a band setting. The difference? Easy, here are three steps:

1. Turn down.

2. Listen and complement the soloist.

3. See steps 1 and 2.

Being at the right volume is even more important than being in tune for this stuff!

For reference, check out any Little Walter compilation, or anything from the ’50s by Sonny Boy Williamson or Muddy Waters. Those really playing this style very well today are guys like Rusty Zinn, Junior Watson, Billy Flynn, and Little Charlie Baty. You can also hear all these licks in the blasting blues-rock stylings of Stevie Ray Vaughan and his hordes of followers, all the way to sophisticated jazz-blues playing of dudes like Robben Ford and the great Chris Cain.

Listening to the rest of the musicians is key in a band situation. Good Chicago blues players weave in and out of the forefront, up and down the fretboard. For your solo, crank your amp and play all of this however you want, because then it’s time for them to follow you. Don’t forget to step out and put on your best blues face!

Kid Andersen Currently the guitarist for Rick Estrin & the

Nightcats, Kid Andersen has recorded and

performed with Charlie Musselwhite, Elvin

Bishop, and many other blues legends.

Originally from Norway, Andersen is now based

in San Jose, California, with the immigration

status of “Alien of Extraordinary Ability.” For

more information, visit rickestrin.com.

Kid Andersen Currently the guitarist for Rick Estrin & the

Nightcats, Kid Andersen has recorded and

performed with Charlie Musselwhite, Elvin

Bishop, and many other blues legends.

Originally from Norway, Andersen is now based

in San Jose, California, with the immigration

status of “Alien of Extraordinary Ability.” For

more information, visit rickestrin.com.