Get deep inside the Super Locrian scale and learn how to add ear-twisting tension to your blues lines.

Chops: Intermediate

Theory: Advanced

Lesson Overview:

• Understand how to create the Super Locrian scale.

• Develop “outside” sounds from augmented triads.

• Create interesting lines using alterations.

Click here to download MP3s and a printable PDF of this lesson’s notation.

In my previous lesson, we explored the concept of generating musical tension and resolution by playing the Super Locrian (or altered scale) over altered dominant 7 chords. Now, let’s continue working with this tonality and investigate some effective ways to reach beyond the typical ascending-and-descending ideas you hear guitarists play when they’re not 100-percent comfortable with a scale.

At this point, some of you may run away with cries of “This is a bit beyond blues for my liking!” While I understand your concerns, I urge you to push on for three reasons: First, this is about as “beyond” as I’m going to take you (unless you really want to get complicated). Second, these ideas can be applied to any scale, from the major scale to the double-harmonic super-Indian pugglebob scale (if such a scale existed). Third, sticking to this tonality for one more lesson will drill it into your ears a little more.

What we’re going for here is a sense of melody, shape, or contour in our lines. Something a little more exciting than those predictable 1st-position blues scale licks—not that we want to lose those, of course. But imagine how great it will sound if you put one of these altered-scale licks in the middle of your standard blues-rock phrases.

The ideas we’re about to look at here aren’t anything new. In fact, if you’re serious about your study, I encourage you to check out the Frank Gambale Technique books, and my favorite, Garrison Fewell’s Jazz Improvisation for Guitar—A Harmonic Approach. Not to mention some serious listening to players who use these ideas in a blues context, and for that, there’s little better than Larry Carlton’s "The B.P. Blues" from his Last Nite album.

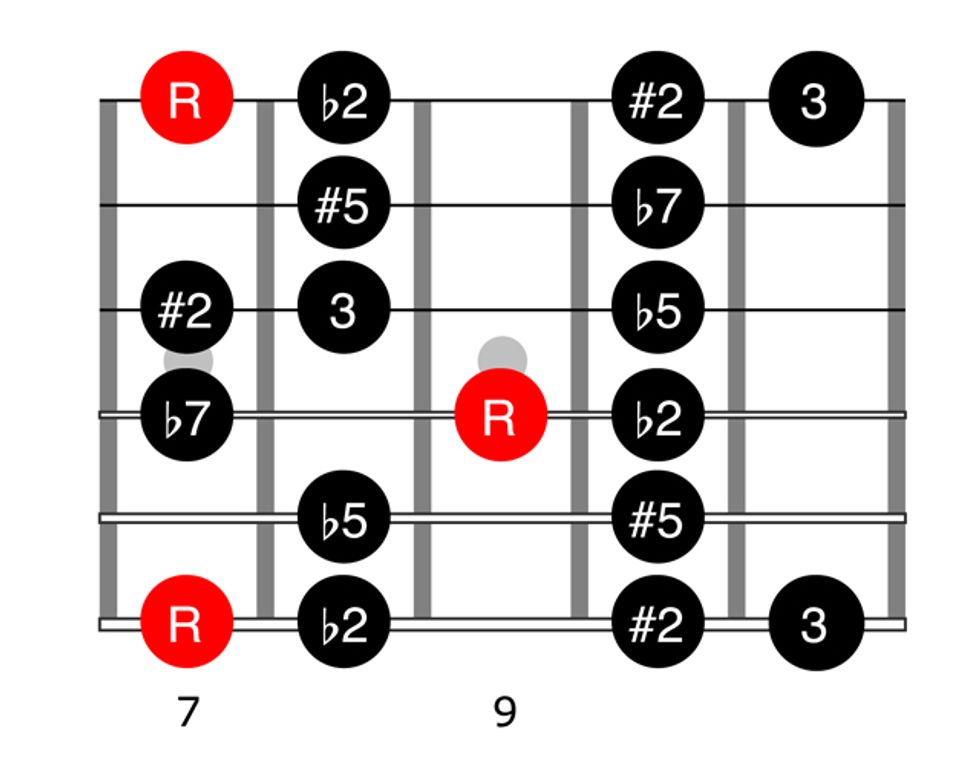

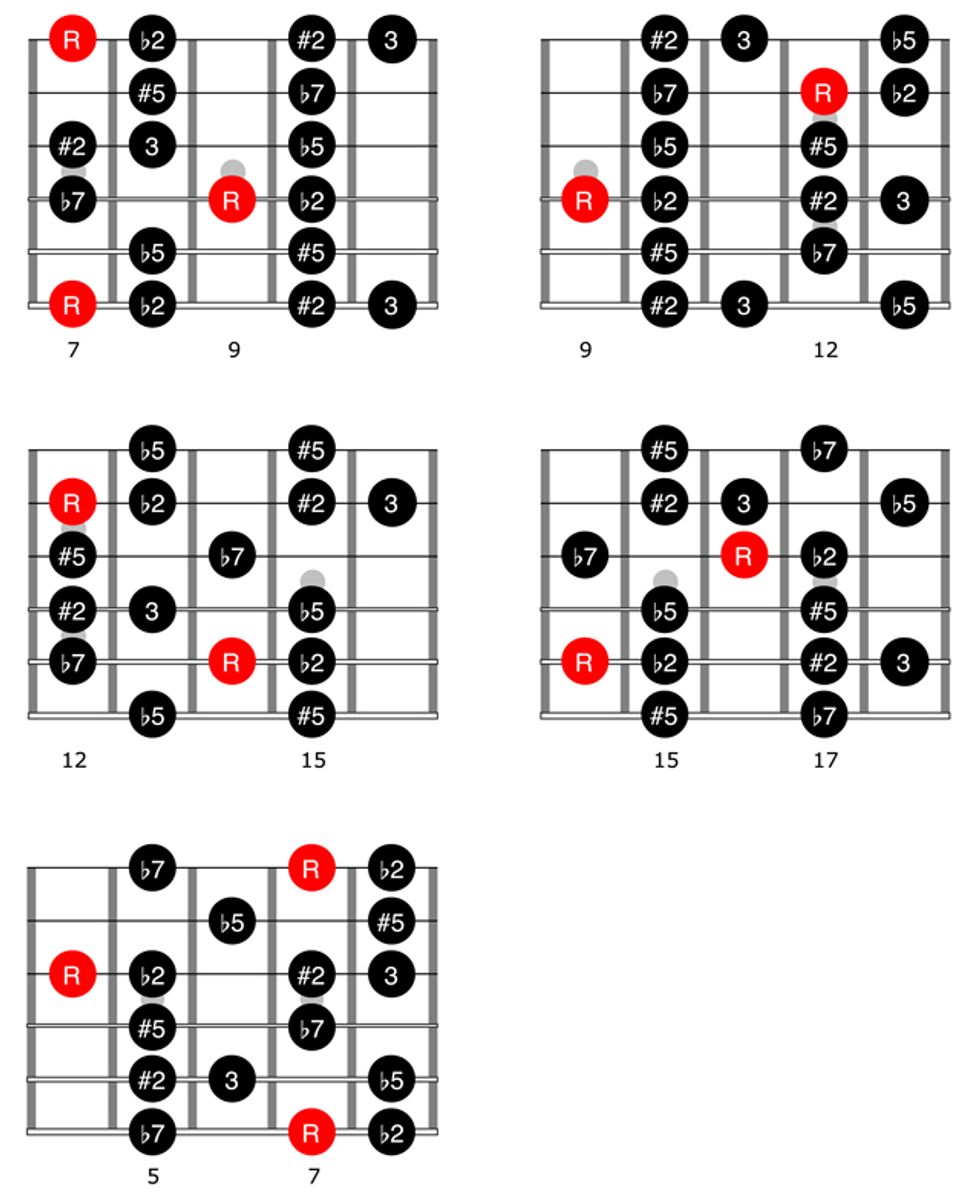

To recap what we covered previously, the Super Locrian scale consists of a dominant 7 arpeggio, along with the four alterations (b5, #5, b9, #9). So it really is the height of dissonance and when resolved properly, it sounds incredible. It’s also the seventh mode of the melodic minor scale, so B Super Locrian is the 7th mode of the C melodic minor scale. For this reason we’ll be playing over a B7alt chord in this lesson, but to keep the accidentals at a minimum, I’ll write everything as though it’s C melodic minor. It also means that if you know your melodic minor scale, then shifting up a fret and playing that scale will give you the desired effect. Let’s start by taking a look at the scale fingerings shown below.

For our first exercise, we’ll play this scale using diatonic thirds. In other words, play the first note, then a note a third higher, play the second note, then a note a third higher, and so forth. Fig. 1 illustrates the process. This is really the most basic form of sequence, but right off the bat it sounds a little more interesting than just running up and down the scale. Again, serious students may want to work out how to play the scale in diatonic fourths, fifths, sixths, and sevenths. It’s a great way to increase your fretboard knowledge and technique.

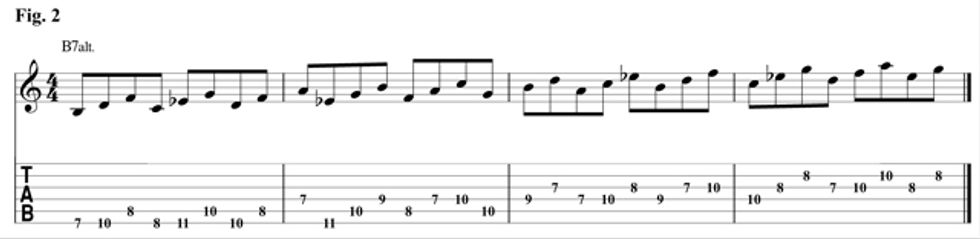

Our second exercise, Fig. 2, is a little bit more harmonically sophisticated because we’ll be playing a diatonic triad off of each note in the scale. I know that sounds complicated, but if we start on B and skip a note we get D, then skip another note and get F—that’s our first triad (B diminished). We can then repeat this process going up the scale.

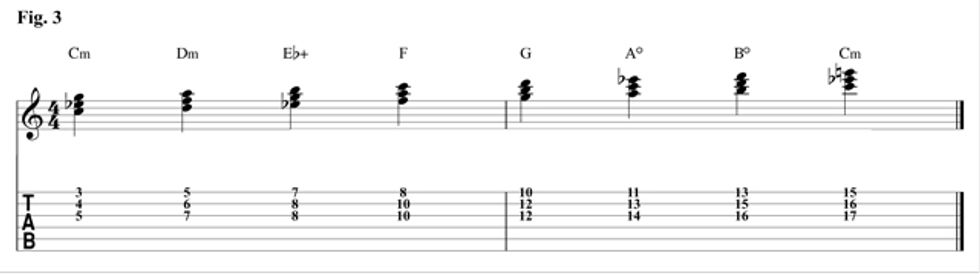

In Fig. 3 I’ve laid these triads out on the fretboard. I recommend you play each triad over the backing track and really listen to the sounds they produce. As an example, the C minor triad consists of a C, Eb, and G, (root, b3, 5). But over a B bass note, the C is no longer the root, it’s a b9; Eb is now the 3 and G is the #5. This is important because it tells us that playing a C minor triad over a B7 sound will imply a B7#5b9.

Next, in Fig. 4, we take the Eb+ (Eb augmented triad) and play it against the backing track, which gives us a B7#5 sound. This is such an easy sound to conjure up, and because the triad is symmetrical in construction (all major thirds), each note can be seen as the root. So an augmented triad based on the root, 3, or #5 will create this great tension. Listen closely to the example I recorded and try to associate the sound with a feeling, so you can pull it out whenever you need it.

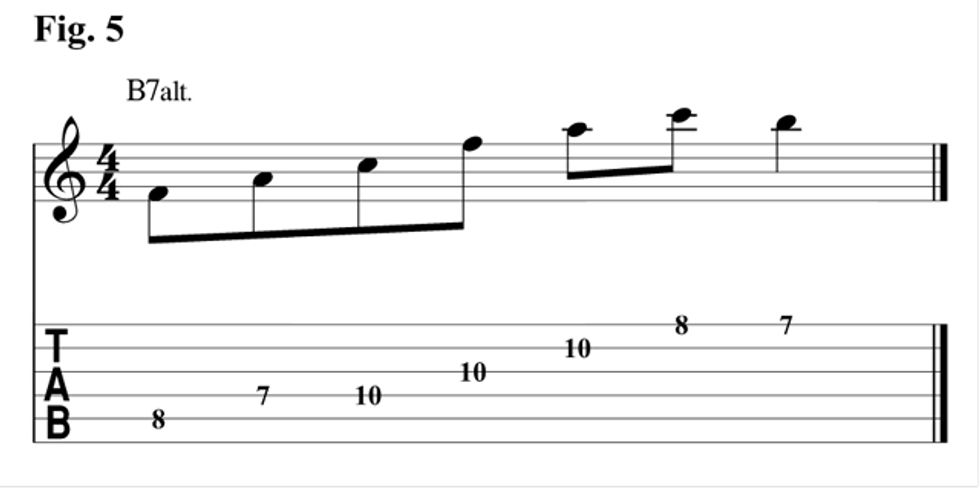

We use a similar idea in Fig. 5, but this time we focus on an F major triad—another triad found in the B Super Locrian/C melodic minor scale. This gives us an implied B7b5b9, which is another cool sound to use in this context. As with the previous example listen to how I use the scale and try it yourself.

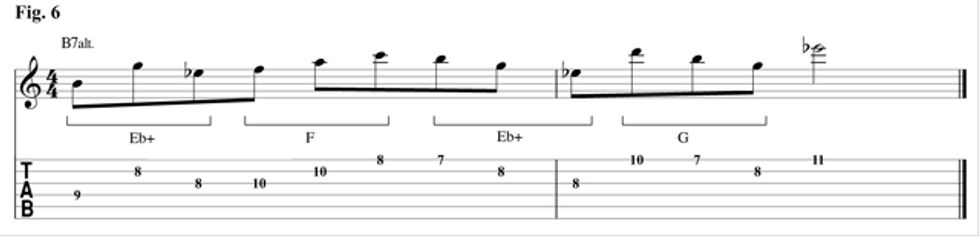

Fig. 6 is a melodic phrase you might play when thinking of the triads contained in the scale. For the sake of study, I’ve marked each triad on the score. Look it over carefully to see how these triads are used together. This idea of using triads from within a scale as the basis of melodies is an instant way to inject something exciting into your playing, so try writing 100 of your own.

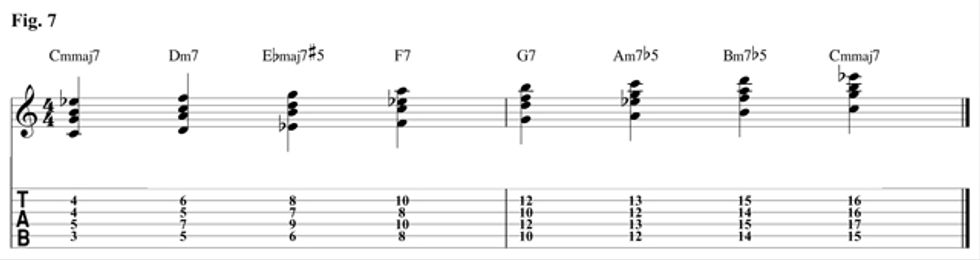

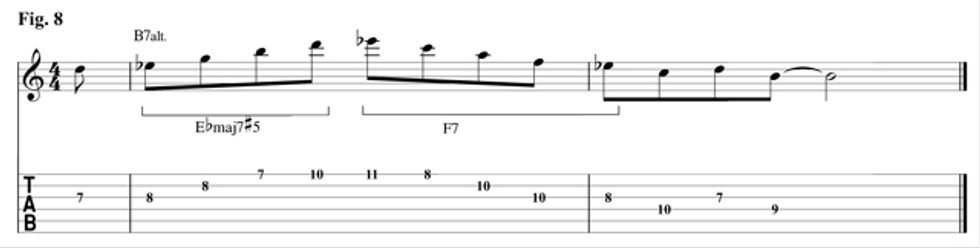

Fig. 7 shows you the diatonic 7 chords found in the C melodic minor scale. As with the triads, I found it very useful to sit with these four-note arpeggios and compose endless lines that integrate them. At the end of this process, I must have had 100 licks and although they may not all be things I remember, they act of doing it dramatically improved my ability to spontaneously create lines when improvising.

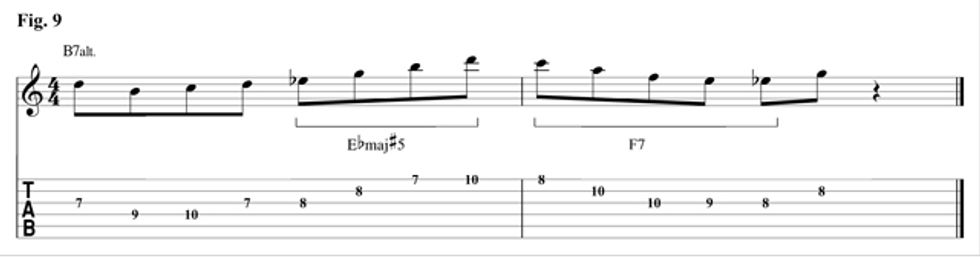

The final lick in Fig. 9 expands on the ideas we’ve just covered. We mix the same two arpeggios, but we lead into the arpeggios with a scalar idea and a chromatic passing tone from the F down to the Eb. This is also important, as I want you to see that when we start using ideas like this it doesn’t mean that everything else we’ve covered goes in the bin. In fact it’s the blending of every concept together that really makes things cook. Just remember, the listener wants to hear your music and ideas—not your exercises—so get creating!

One last, rather daunting, prospect: We’ve only looked at these ideas in one position of the CAGED system, so as promised last month, here are the other four for you to start getting under your fingers. Use them over the B7alt backing track below. Treat them just as we have this one by applying the same approaches, and before long you’ll be playing outside so well you’ll feel like you’re in the park.

B7alt. Backing Track

Levi Clay

Levi Clay

Levi Clay is a London-based guitar player, teacher, and transcriber. His unique approach to learning keeps him in constant demand from students the world over, and his expertise as a transcriber has introduced his work to a whole new audience. For more information, check out leviclay.com.