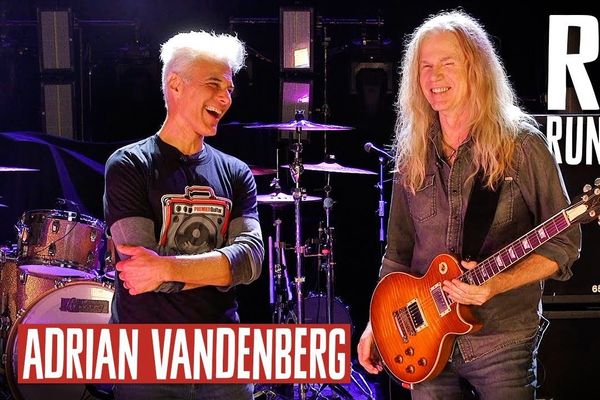

Brian Setzer breaks down his love-hate relationship with vintage Gretsches and the roots that fed the dizzying array of styles—from bluegrass banjo to archtop jazz and rockabilly revelry—on his new album "Setzer Goes Instru-MENTAL!"

Brian Setzer with a sparkle-finished Gretsch G6120TV Hot Rod

stocked with TV Jones pickups. Photo by Russ Harrington

With his trademark pompadour, flashy rockabilly licks, swingin’ jazz comping, and expert showmanship, Brian Setzer is one of guitardom’s most iconic musicians. But he wouldn’t have achieved such pinnacles of fame if he weren’t a deeply musical guitarist, as is apparent from one listen to his latest effort, Setzer Goes Instru-MENTAL! It’s his first entirely vocal-less outing, and the disc’s exciting synthesis of rockabilly, bluegrass, and jazz make for an instantly pleasurable listen.

Setzer, 52, has been playing guitar for four decades now. He grew up in the Long Island, New York, town of Massapequa and started playing his first instrument, the euphonium, at age 8 before focusing on the guitar in his teens. While he copped licks from his father’s rockabilly records, he also became fascinated with jazz and periodically made trips to nearby Manhattan to sneak into clubs like the Village Vanguard.

In the early 1980s, Setzer fronted the Stray Cats—a rockabilly trio that became hugely popular in America after making a splash in Europe. On hits like “Rock This Town” and “Stray Cat Strut,” Setzer sang and mated hot rockabilly licks with the occasional fancy jazz chord—a sound far removed from the diatonic electronic timbres that came to rule the era.

Starting in the mid ’90s, Setzer realized a longtime dream, one he’d had since visiting those New York jazz clubs where large ensembles took residencies. He formed a 17-piece big band, the Brian Setzer Orchestra, which specializes in the sort of swing and jump blues heard on their 1998 breakthrough album, The Dirty Boogie—which spawned a massive hit with the Louis Prima cover “Jump, Jive an’ Wail.” Since then, Setzer has kept things eclectic: His Christmas tours with the BSO are perennial favorites, and his albums have run the gamut from roaring, gas-guzzling trio outings like 2001’s Ignition to the retro-rockabilly tribute of 2005’s Rockabilly Riot, Vol. 1: A Tribute to Sun Records, the jazzy interpretations of classical gems on 2007’s Wolfgang’s Big Night Out, and 2009’s film-noir-inspired Songs from Lonely Avenue.

We recently chatted with Setzer—who’s quite the amiable cat—about his preferred gear (vintage and new) and how his jazz, rockabilly, and country roots figure into the excellent new Setzer Goes Instru-MENTAL!

I understand you’re a big-time gear aficionado. What guitars did you play on the record?

I played a 1959 Gretsch 6120 on one song, and then it kind of fell apart on me. But more on that in a minute. So then I played my various 6120 signature Hot Rod models—whichever one was tuned up and ready to go at a given time. On the acoustic side, I mostly used my treasured 1963 D’Angelico Excel, as well as an old Stromberg—which has a huge, booming sound—for rhythm tracks in the Freddie Green style.

What about amps?

I mostly used a 1963 Fender Bassman. That’s basically my meat-and-potatoes setup—a 6120 through a Bassman, sometimes with an old blonde Fender Reverb unit that matches the amp. When I began recording the album, after I’d gotten a perfect track down, I noticed that one of the speakers in the Bassman was blown. Luckily, though, the other speaker had been mic’d, so the cut came out okay. Regardless, I shifted gears and brought in another Bassman—I’ve got a mess of them—also a ’63. I really like amps from that one year.

Why is that?

Fender just seemed to get things right in ’63, when they put a solid-state rectifier in the Bassman. Before that, it had a tube rectifier, which tends to sound kind of mushy to my ears. The solid-state rectifier sounds more tight and defined, giving me the clarity I need for my style.

Are your Bassmans stock or modified?

I got some of them in 100-percent original condition, and so I’ve left them that way. I’ve updated others—including all the ones I take on the road—that already had mods when they came to me. I had everything rewired with heavy-duty cables and threw 30-watt Celestion speakers in there. That way, I can get a pretty consistent sound.

So what happened to that ’59 6120?

After I played a song on it, two of the frets slid right out, the bridge was all out of adjustment, and I noticed that the neck had become pretty bowed. It wasn’t pretty. But these things happen when you’re dealing with a guitar that’s more than 50 years old.

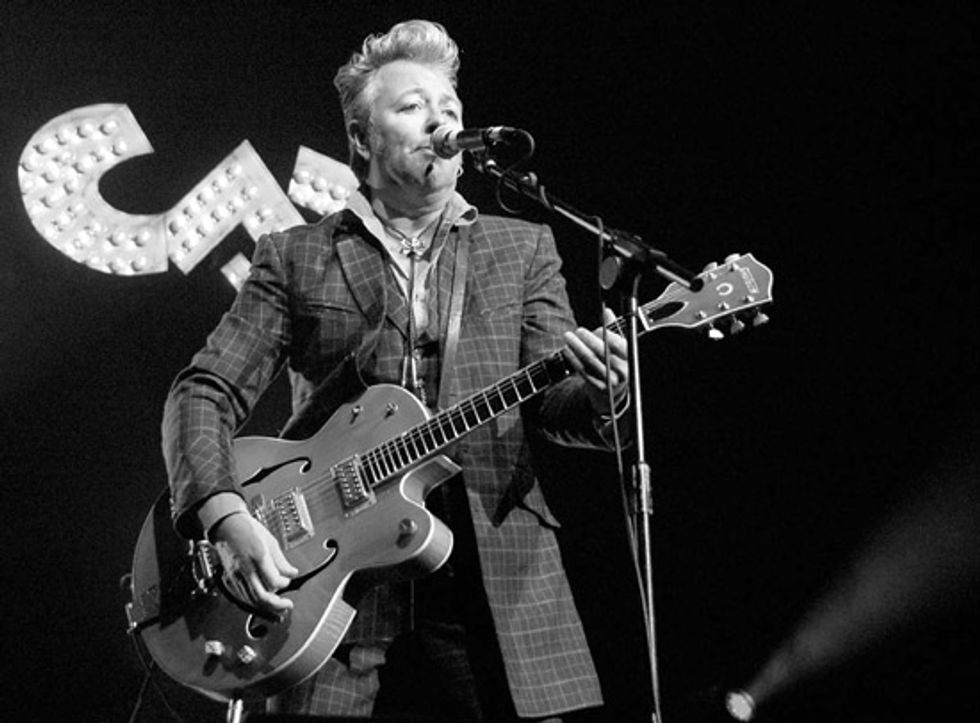

A long-maned Setzer wails onstage with the Stray Cats at the Coogee Bay Hotel

in Sydney, Australia, in December 1990. Photo by Denise OHara

Has that guitar been a longtime companion?

Yeah, I bought it a long time ago from a guy on Long Island when I lived there, and incidentally it’s a really good one. Guitarists tend to romanticize vintage instruments, but the old ones are really so hit-and-miss. I rate them “Monday through Friday,” Monday being the worst. With a Monday guitar, it’s like the guy working at the factory started the week with a hangover and a fight with his wife, which translated to a crummy instrument. With a Friday guitar, the guy was in a great mood and was pumped up for the weekend, so he makes a beautiful instrument. That ’59 is definitely a Friday guitar—when it’s in perfect working order, it plays and sounds incredible.

How would you compare your new guitars to their vintage counterparts?

The new ones are ready to go right out of the box, but the old ones take so much to play right. It’s not like you can just drop ten grand on a ’50s guitar, plug in, and away you go. In order to make it playable, you have to make it so unoriginal as to ruin the value of the guitar—just as taking apart an old car and putting in a new engine might improve the performance but makes it worth much less.

What sort of mods does it take to get an old guitar up to snuff for you?

Take 1959 Gretsches: I’ve got them and I love them, but they tend to be unplayable in original condition. First of all, you’ve got to take the frets out, because they’re useless—they’re just these tiny little tacks. The neck is usually just a mess and has to be planed and straightened by a good luthier. Often, it has a reverse-bow so bad it has to go in a steamer. The bridge is just no good and will fall right off the guitar if you play too hard, so it’s best to pin in a Gibson-style Tune-o-matic. The zero fret is also no good—it doesn’t really improve the intonation like it’s supposed to—so you’ve got to yank that out and fill up the empty slot. Honestly, sometimes it just isn’t worth the aggravation—just pick up a new guitar. It’s hard to exactly replicate something that’s five decades old, but the new ones come pretty close—you can dial in a sound that’s not very far from a vintage one.

To your ear, how do vintage and new guitars compare?

Man, the best ’59s have got a really warm crunch that’s great for really straight rockabilly—probably because the wood has been sitting around for so long. You plug those things in, and the sound is just huge and woody. The new ones actually sound pretty similar, but a little less magical, which is why the best old ones are so expensive.

Setzer Goes Instru-MENTAL! is filled with impressive jazz blowing. What is your background in that idiom?

Early on, I learned how to read and write music through a teacher who taught me the rudiments. We went through all the Mel Bay books, which I still think are great and would recommend to any budding guitarist. And then the teacher basically said, “I can’t teach you anymore.” So I had to get on two busses and walk a mile carrying my Gibson ES-175 to the studio of a more advanced guitar teacher, who taught me chords, scales, and theory, how to play all kinds of inversions and extensions, and how to play over chord changes. He showed me his conception of the guitar, which was a fancy jazz sort of thing—something that has been part of my playing ever since.

Which did you get into first, jazz or rockabilly?

I learned both styles around the same time. Things were much different when I was coming up. You couldn’t just listen to any style of music on the internet with the click of a button. You had to make a bit of an effort to find and listen to music. In New York, we had some of the best jazz players around, so I was exposed to plenty of jazz. We didn’t have much in the way of country and rockabilly players, but my dad came back from Korea with records by musicians like Johnny Cash and Jerry Lee Lewis—he got these from some of his army buddies who were from the South—and I really got into the music and copped some of the licks on the guitar. It all sounded good to me, and it just seemed like a natural thing to mix everything up.

Setzer rocks a bolo tie, a signature Gretsch G6120SSL (with dice-topped neck- and

bridge-pickup Volume knobs), and an Opry-approved suit at a September 2008

gig in Paris. Photo by Andi Hazelwood

Bluegrass is also part of the mix on the new album—you play songs by the likes of Bill Monroe and Earl Scruggs.

Yeah. A little bit of country and bluegrass sneaks its way into my playing, too. Basically, all of the stuff that my ear likes—rockabilly, swing, jazz, rock ’n’ roll—finds its way to my fingers. It just all comes out. The bluegrass influence goes way back to when I was a kid and my grandfather gave me a banjo. I taught myself how to pick in the bluegrass style, because I thought it was the coolest thing with all those speedy runs. All these years later, I’m playing things like “Lonesome Road” and “Earl’s Breakdown.”

What was your writing and arranging process like for the record?

I wrote seven songs with lyrics, then I started fooling around with the Bill Monroe song “Blue Moon of Kentucky,” just running through the melody and chords on the guitar. At that point, I decided to backtrack and make this an instrumental record, since that’s something I hadn’t done before. As for the writing and arranging, basically I just wrote out the melodies and chords in lead-sheet form. For the chords, I fooled around on the guitar and came up with a lot of substitutions—whatever sounded right to my ear. For instance, in “Earl’s Breakdown,” where I broke out my Scruggs banjo, one of the original progressions is something basic like G–C–G–Em–E7, but I play G–Gmaj7–G7–Gm6—crazy jazz stuff that happened to work really well. My bassist, Johnny “Spazz” Hatton, and drummer, Noah Levy, were part of the writing process, too, since they came up with their own parts based on my skeletal notation.

What about the recording process?

When I finished writing the album, I wanted to go into the studio and get everything down on tape as quickly as possible because I was so excited about it—just like any other album I’ve recorded. I like to keep things simple: Pull out the best old microphones, put up the Neumanns, put up the Sennheisers, bring in my old gear, and just play and start making a record. Most of the new record was recorded live—just a few guys in a room—and for the selections without drums, like “Far Noir East,” we used a click track to keep things rhythmically tight.

The recording process would have been difficult or even impossible without players as talented as Johnny and Noah— musicians who can throw down exactly what’s needed just by looking at charts or taking a few simple instructions. I don’t have the time or patience for guys who can’t read and learn quickly. I’ve just got to get things recorded quickly while I’m feeling inspired.

What appeals to you most about how Johnny and Noah approach your music?

Photo by Andi Hazelwood |

How’d you end up in Minneapolis?

It started out because my wife is from here and we kept coming back to visit her family. I quickly realized what a great town Minneapolis is. It’s not a shuck-and-jive or business-type environment—it’s a real city filled with real people, and I really enjoy living and making music here.

Your chops sound as sharp as ever. How do you maintain them?

I shoot a lot of pinball [laughs]. That actually makes things bad—don’t do that, because it gives you a tennis elbow or a carpal [tunnel] type of thing. Seriously, I maintain my chops simply by playing. After all these years, I don’t think a day goes by when I don’t pick up the guitar. Even if I’m playing something I learned when I was 15 years old, it’s really still a thrill just to sit down and play the thing.

Brian Setzer’s Gearbox

Guitars

1959 Gretsch 6120 with TV Jones Classic pickups, assorted Gretsch 6120-based signature models with TV Jones-designed pickups, 1963 D’Angelico Excel, 1930s Stromberg archtop

Effects

Early-1960s Fender Reverb unit, vintage Roland Space Echo units

Amps

Various 1963 Fender Bassman combos —some modified with heavy-duty wiring and 30-watt Celestion speakers, 1961 Fender Twin-Amp

Miscellaneous

D’Addario EXL110 strings (electric), D’Addario EJ17 strings (acoustic), medium D’Addario or Fender picks