Dream Theater’s twin shred deities—guitarist John Petrucci and bassist John Myung—discuss the hoopla over founding drummer Mike Portnoy’s departure, their tendon-thrashing hand workouts, and the recording of their latest epic, A Dramatic Turn of Events.

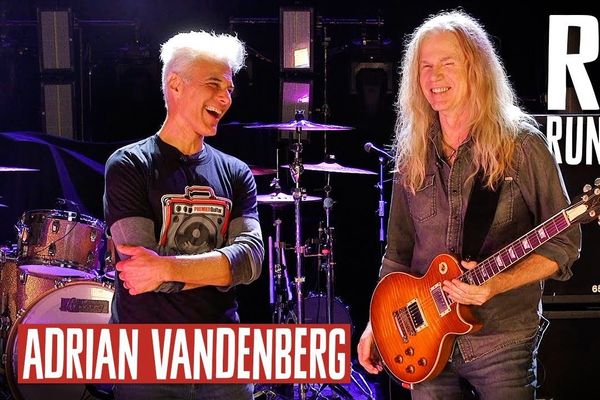

Dream Theater bassist John Myung (left) and guitarist John Petrucci. Photo by Michael Lavine

A little over a year ago, just as the members of prog-metal giant Dream Theater were contemplating the logistics of their next album, the unexpected—no, the unthinkable—happened. Drummer Mike Portnoy, a founding member and the band’s spokesperson and leader since its inception at Berklee College of Music in 1985, quit. Portnoy had toured with Avenged Sevenfold in the spring of 2010 after the band’s drummer, Jimmy “the Rev” Sullivan—who idolized the Dream Theater drummer—passed away unexpectedly. Miscommunication and dissatisfaction must’ve abounded in both bands, because Portnoy apparently thought he had a chance of becoming a full-time member of the younger, more commercially successful AX7, but guitarists Zacky Vengeance and Synyster Gates claim they hired Portnoy primarily to honor their deceased bandmate. By the time Portnoy realized the direness of the situation, Dream Theater had moved on.

Shortly after Portnoy gave his notice, seven of the world’s top drummers—Mike Mangini, Marco Minnemann, Virgil Donati, Aquiles Priester, Thomas Lang, Peter Wildoer, and Derek Roddy—were invited to New York City to audition for the vacant slot. To make the already nerve-racking auditions even more terrifying, the band filmed the three-day process for a documentary-style reality show called The Spirit Carries On. The grueling audition consisted of three parts: Phase one covered songs, phase two entailed jamming (presumably in odd meters that aren’t even in the same universe as the 12-bar blues!), and phase three dealt with riffs. In the end, Berklee College of Music professor Mike Mangini got the gig.

On September 13, 2011, Dream Theater released A Dramatic Turn of Events, which was produced by guitarist John Petrucci. We caught up with Petrucci and bassist John Myung to broach the touchy subject of Mike Portnoy, get more details about the audition process and the new album, and talk gear.

First, let’s discuss the question on everyone’s minds: Were there signs Mike Portnoy had been thinking of leaving prior to his announcement?

John Petrucci: No. It came out of the blue. We said everything we could to try to convince him that it was a mistake, but ultimately it was something he had to do.

John Myung: In hindsight though, you could kind of connect the dots. When you look back, you can pick up on vibes and stuff. But it wasn’t like you thought it was actually going to happen.

I’ve read that Portnoy says when he later reached out to you guys to try to reconcile, he only heard back from your lawyers.

Petrucci: By that point, we had reconstructed our infrastructure and moved on in a major way. We filmed the movie, had the studio time booked, and chose Mike Mangini who then left his tenured professorship at Berklee. And then Mike came to us and said, “Hey, I want to come back.” We were like “Really? Are you kidding me—after all that?”

Have you guys talked?

Petrucci: It’s ongoing. When you’re a band that’s been together for this long, there are a lot of business things involved. It’s very similar to a divorce; you have to work out all of the details.

Let’s talk about the drummer auditions. What songs did you choose and why?

Petrucci: Well first of all, we didn’t want to overwhelm everybody and have them learn an hour’s worth of music or anything like that. We wanted to make sure we had a varied array of songs that make up our style.

Myung: And the different elements that we incorporate into our live shows. We also wanted to get a sense of how they would approach the different songs.

Petrucci: We chose “The Dance of Eternity” for its real technical and progressive aspect. Then we chose “A Nightmare to Remember,” because it’s important to have a drummer that can kick hard, play double bass, and do all of that great stuff. “Nightmare” not only has that but it also has more sensitive groove moments. And then we chose “The Spirit Carries On,” which is moodier and simpler, and all about the feel and the flow. That was a good balance. If a drummer can play all of those songs with us and have them feel comfortable, then we’re on the right track.

When you watch the auditions, you can hear that some of the drummers added their own twist to the songs—and you can tell that didn’t go over so well.

Petrucci: I think for any musician joining an established band, the first focus should be on making it sound like the band. If you come in and take a completely different approach and change the style up and start doing your own fills, it might be something cool technically and musically, but it’s ultimately not going to leave a really good first impression. We’re looking for a new drummer and we have a discography of many, many songs plus a worldwide fan base. It’s not only us as band members, but it’s also our fans who are going to want to hear the songs played and have it sound like Dream Theater. The audition environment is not really the place to try and change things up and reinvent our sound.

Myung: We were looking for more of a classical interpretation. It was more like, “Let’s run through these songs and see how great and natural they feel,” rather than looking for the improvisational side of it. You can have two people play the same part and it feels different. Every drummer has their own way of interpreting and phrasing things. The one thing unique about every musician is how they interpret the subdivisions. How they group the notes and cluster the subdivisions.

Dream Theater (left to right): Mike Mangini, Petrucci, James LaBrie, Myung,

and Jordan Rudess. Photo by Michael Lavine

Like where they’re hearing the accents in, say, an asymmetrical phrase?

Myung: Yeah. Like, would you think of 9/8 as 6/8 then 3/8 or 3/8 then 6/8? It’s a total feel thing, but it’s sort of like, “Are we on the same page, musically?”

Tell us about the writing sessions for the new album.

Myung: It reminded me of the early days, when it was just me sitting in front of John and Jordan [Rudess, keyboards] and saying, “I’ll play this part, you play this part, and we’ll record it.” A lot of the early stuff was stuff I would first work on with John and Kevin [Moore, original DT keyboardist] and then we would bring it to the band. But once our [1992] album, Images and Words, took off and went gold, we were just like this machine. We started touring and writing and doing everything together.

So, in some ways, this was like we were back to the beginning. It was a combination of writing as a group and not as a group. The sessions were really mellow and laidback. We were all playing at acoustic volumes, which made the dynamics of the communication different. It felt less on the go and more meditative.

Petrucci: I had stuff that I worked on ahead of time—demos, songs, and my riff library—but, ultimately, John, Jordan, and I went into the studio and wrote together. As we were writing, we demoed it all. I programmed the drums using Superior Drummer in Logic. After we finished the songs, we sent them to Mike Mangini. About two-and-a-half months later, when we came to record, he had templates of all the songs—all the tempo maps and markers. It’s pretty incredible to watch and record somebody like that. He came in and brought everything to life. It’s a lesson for all professional musicians out there—not only about being incredibly skilled and gifted, but also about being prepared.

How do you balance maintaining and/or furthering your prodigious technique while working on the demanding live set and committing it to memory?

Petrucci: Things go in stages. Right now, my focus is on the fact that I know I have to tour, and the first show is September 24, so I have to be able to play such and such songs. There’s a whole process of learning them—isolating the guitars and going back and learning what I played—then memorizing it and practicing the difficult parts. It’s not the time to be searching out and practicing new things: The focus is the short-term goal. Once I get comfortable and I’m on the road, or when the tour cycle is done and I’m home, then I can take a deep breath and start asking questions again, start learning new things.

Myung: I’ll know what the set is going to be at least a month prior to a tour. Then I put myself on a schedule where I at least run through every song once a day, going through the set for two or three hours. Some of the songs are really long, so it can take over ten minutes to get through it once. Even if you’ve played it for an hour, you’ve only gotten through it five times or so. Our set is like two hours, and we’ll have a master set with extra songs in it, so maybe there will be—from start to finish—like, three hours of material to run through. Then, slowly it starts to come together.

Apart from just running through the set, I also have to get my hands to do what I want them to do, which is a whole other thing where I just warm up. I have a certain procedure that I do with my hands before I feel totally dialed in. It’s two or three hours of subtle movements. And it’s not anything that I learned from a book, it’s just playing.

Are you able to find time to do this every day?

Myung: It’s a part of my life now, so I need to do it. And before every show I have to do it.

You run through the whole two-hour routine before every show?

Myung: Yep. Absolutely. Usually, we’ll drive overnight on a bus, check into a hotel, and soundcheck will be sometime after 4 o’clock, and then we’re usually on at 9. Between soundcheck and the actual showtime—as soon as soundcheck is over—I disappear and find a room, then immediately start my sequence. It really has to be that way, because you can’t give it your all and feel good about what you’re doing if your hands, if the physical side of things isn’t ready. You have to condition yourself to be able to play the way you want to play.

Petrucci with one of his Music Man JP6 guitars. Photo by Michael Hurcomb

John P., in the past you’ve said you used to think of alternate picking and legato playing as two separate approaches, and that legato playing almost felt like cheating because you don’t have to pick every note. Later, you combined both approaches to play at what you call “hyper speed.”

Petrucci: Basically, if you’re alternate picking consecutively and then you stop to leave room for legato, the direction your pick left off and starts up again is where it normally would be if you were alternate picking, like where the downbeat is.

Do you mean like “down-up” then legato then starting again “down” on the next beat?

Petrucci: That’s the simplified version, but yeah, the downbeats still fall where they would normally fall, like on the beat.

I know you also make it a point to practice the same line starting with both a downstroke and an upstroke. Do you do that with these types of combination lines as well?

Petrucci: Yeah. It’s important to work on that sort of thing. I think this type of thing is a bit more natural. If you’re improvising it’s where it ends up, depending on where you’re starting. But it’s always good to practice things starting with different strokes so that you feel comfortable both ways. It’s funny, I was talking to Mike Mangini about this. He’s very into technique and plays at a highly developed level, and alternate picking is a very similar parallel to the left-right hand-foot coordination that drummers employ. Like if you have a weak hand or a weak foot or a weak upstroke, and you practice to make it strong and even.

Let’s talk gear now. Tell us about your Music Man instruments.

Petrucci: I started working with Music Man over 11 years ago, and they’re an unbelievable company. We started with the original signature model, and now we have a whole line. Instead of discontinuing a model, we keep it available for sale. The cool thing is that they’re all unique in some way. It’s like having different spices in your spice rack.

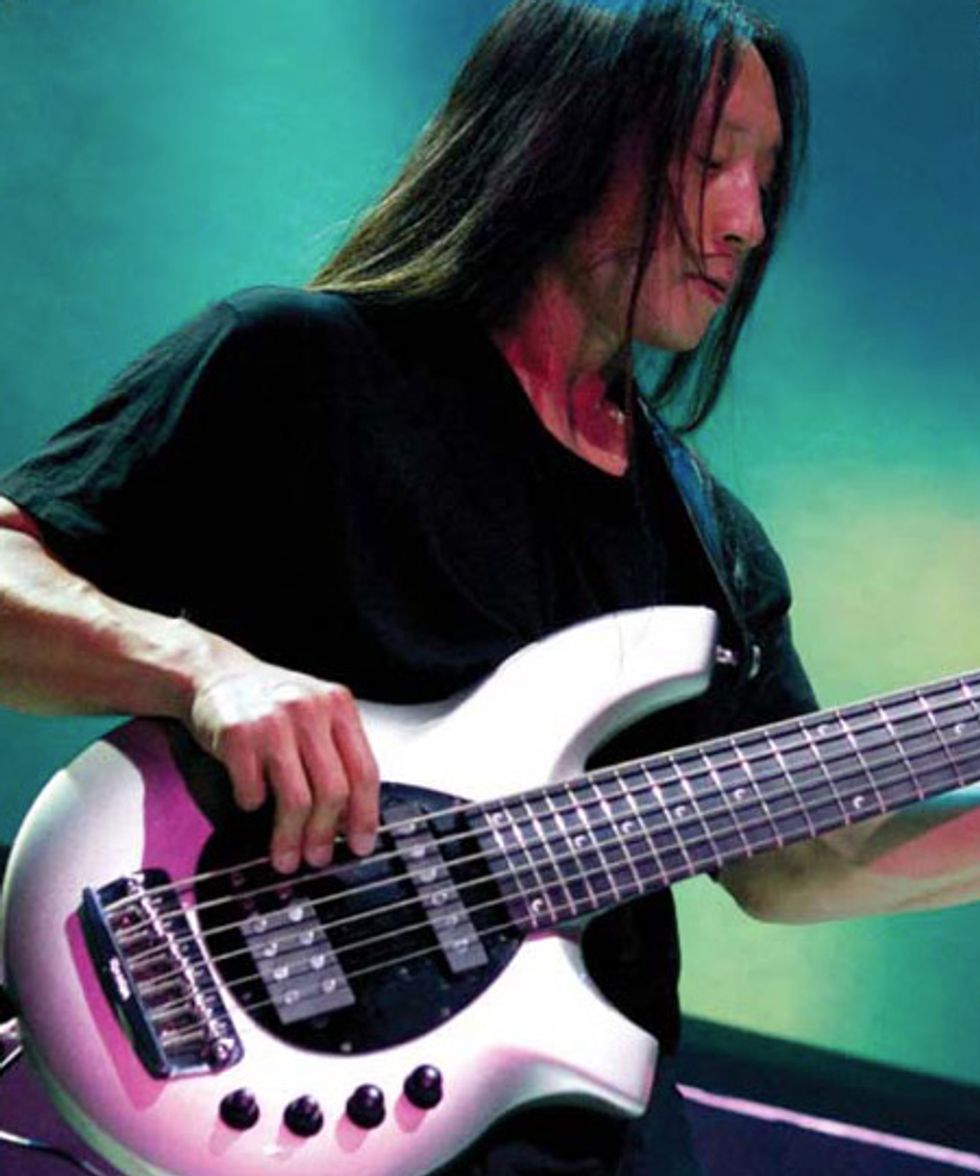

Myung: I’m using custom Music Man 6-string Bongo basses. I’ve had the one I’m playing now since last August, and it’s the best bass I’ve ever played.

Myung with one of his Music Man Bongo 6-string basses. Photo by Michael Hurcomb

From what I understand, it’s the first 6-string bass Music Man ever made.

Myung: That’s right. The original Bongo prototype was a 6-string, but the neck and the body had been increased proportionately. I was living with that for a while, but it got to the point where it didn’t feel completely right, so we went with a tighter spacing and I went with superimposing six strings on a 5-string Bongo. That was close, but I wasn’t completely sold on it, so I kept playing the standard 6-strings, and then during the last tour I decided maybe the magic formula is keeping the body of the bigger scale but using the 5-string neck. That proved to be the winning combination. It’s basically the 5-string neck dimension, but with six strings. It’s really changed my world and made my life so much better.

John P., you’re partially responsible for making the Mesa/ Boogie Mark IIC+ the most sought-after vintage Mesa, and you’ve consistently used Boogie amps over the years. Your rig now features the Mark V, which has Mark IIC+ and Mark IV modes. Can the Mark V replicate those amp tones exactly?

Petrucci: It’s really, really close. You can’t even tell the difference. The whole record was done with the Mark V. All the rhythm guitars were done with the Mark IV mode, and all the guitar solos were done with the IIC+ mode. It sounds so incredible. I’ll have the Mark IV and IIC+ in the studio and A/B them, and not only can you not tell the difference, in many cases, the Mark V beats them with the improvements they made.

How so?

Petrucci: The Mark V uses newer parts and technology and has a more focused sound, in general.

Both of you have also incorporated the Fractal Audio Axe-Fx into your rigs.

Petrucci: When I went into the studio, the Fractal guys came down and mic’d up my Mark V. We got this great guitar sound and they modeled it as closely as they could. I was then able to use that bank of Axe-Fx sounds to comfortably write and demo the album. It was incredibly convenient and simple, and it sounded amazing. Once the writing process was complete, I then mic’d up the Boogie and rerecorded all the guitars with the Mark V. Here and there, we ended up keeping the scratch guitar performances with the Fractal if it was something that just had that certain performance magic—mostly some clean stuff and a couple of short lines.

Myung: Right now, the Axe-Fx Ultra is the hub for all my effects. In the studio, I did a lot of modeling with the guys from Fractal Audio. We modeled a whole bunch of things that I needed but would be too hard to take on the road—stuff like a Pearce BC1 preamp, which I really like.

Photo by Rick Wenner

Is that the one Billy Sheehan uses?

Myung: Yep.

Could the Axe-Fx eventually replace your amps?

Myung: Not for bass—at least not now. But it’s great as far as providing supplemental characteristics. What I’ve found is that, to get a cooking bass sound, what you need is a heat source. You really need tubes and heat, because it offers warmth, dynamics, and natural compression.

Petrucci: The Axe-Fx is an awesome unit—it’s replaced most of the effects in my rack, and it’s doing all of the delays and harmonies. I have a small pedalboard for all of the front-end stuff. Ultimately though, when it came time to track the guitars, for me, I don’t know if it’s too soon to call it old-school, but the whole guitar-into-an-amp-into-a-cabinet-pushing air-being mic’d thing—I’m addicted to that. It’s something that I’ll never stop doing. Every time I try something like a speaker simulator or a modeling thing, as great as the technology is—and it gets better and better and better—I’m still married to that. There’s nothing better.

John Petrucci's Gearbox

Guitars

Music Man John Petrucci signature JPXI 6-string, Music Man John Petrucci Ball Family Reserve (BFR) 6-string, Music Man JP6 6-string, Music Man JPXI 7-string (with low B string), Music Man JP BFR 7-string (with low B), JPXI 6-string (in D tuning—standard tuning dropped a whole-step), Music Man John Petrucci BFR (in D tuning), Music Man John Petrucci BFR baritone (in A tuning), Taylor 30th Anniversary 712ce

Amps

Mesa/Boogie Mark V heads, Mesa/Boogie Rectifier 4x12s with Celestion Vintage 30s

Effects

Fractal Audio Axe-Fx Ultra (at press time, tech Maddi Schieferstein was working with Fractal Audio’s Matt Picone to program an Axe-Fx II for Petrucci), Dunlop CryBaby DCR2SR rack wah, Majik Box Body Blow, Boss PH3 Phase Shifter, MXR EVH117 Flanger, G Lab BC1 Boosting Compressor, Ernie Ball 25K Stereo Volume Pedal

Strings, Picks, and Accessories

Ernie Ball .010–.046 Slinkys (for standard tuning), .056 for low B on 7-string guitars, Ernie Ball Slinkys for D tuning sets (.010, .013, .017, .028, .042. .052), Ernie Ball Slinkys for A baritone tuning (.012, .016, .022p, .036, .048, .064), Ernie Ball Earthwood Extra Lights (for acoustic), Jim Dunlop Ultex Jazz III 2.0 mm picks, TC Electronic PolyTune, Furman AR-PRO AC line-voltage regulator, Axess Electronics CFX4 Control Function Switcher, Axess Electronics GRX4 Guitar Router/Switcher, Axess Electronics FX1 MIDI controller, Framptone Amp Switcher, custom Mark Snyder interface/switcher, Mogami cable with Neutrik connectors, Finger-Ease guitar-string lubricant, DiMarzio ClipLock straps

John Myung's Gearbox

Basses

Music Man Bongo 6-string basses

Amps

Demeter HBP-1 preamp, Demeter VTHF-300M tube power amp, Demeter VTDB-2B tube DI, Radial JD7 Signal Distribution Amplifier, Radial JDX Reactor direct box/speaker simulator, Demeter BSC-212 2x12/1x8 cabinet, Mesa/Boogie Dual Rectifier head and 4x10 cab (for dirty tones)

Effects

Fractal Audio Axe-Fx Ultra, Demeter HXC-1 HX compressor, Little Labs IPB Jr. Phase Adjuster, Moog Taurus 3 bass pedals, Fractal Audio MFC-101 MIDI foot controller, Ernie Ball volume pedal

Strings, Picks, and Accessories

Ernie Ball strings (.032, .045, .065, .080, .100, .130), Furman AR-1215 AC line-voltage regulator, Shure UR4D wireless, Whirlwind Selector A/B box, Korg DTR-2000 tuner, Mogami cable, Levy’s Leathers straps, Jim Dunlop StrapLoks