Other players are supposed to be able to follow us. We set up chord changes like drummers set up sections of a song with fill. It is one of our primary functions. We always have to be first on the scene.

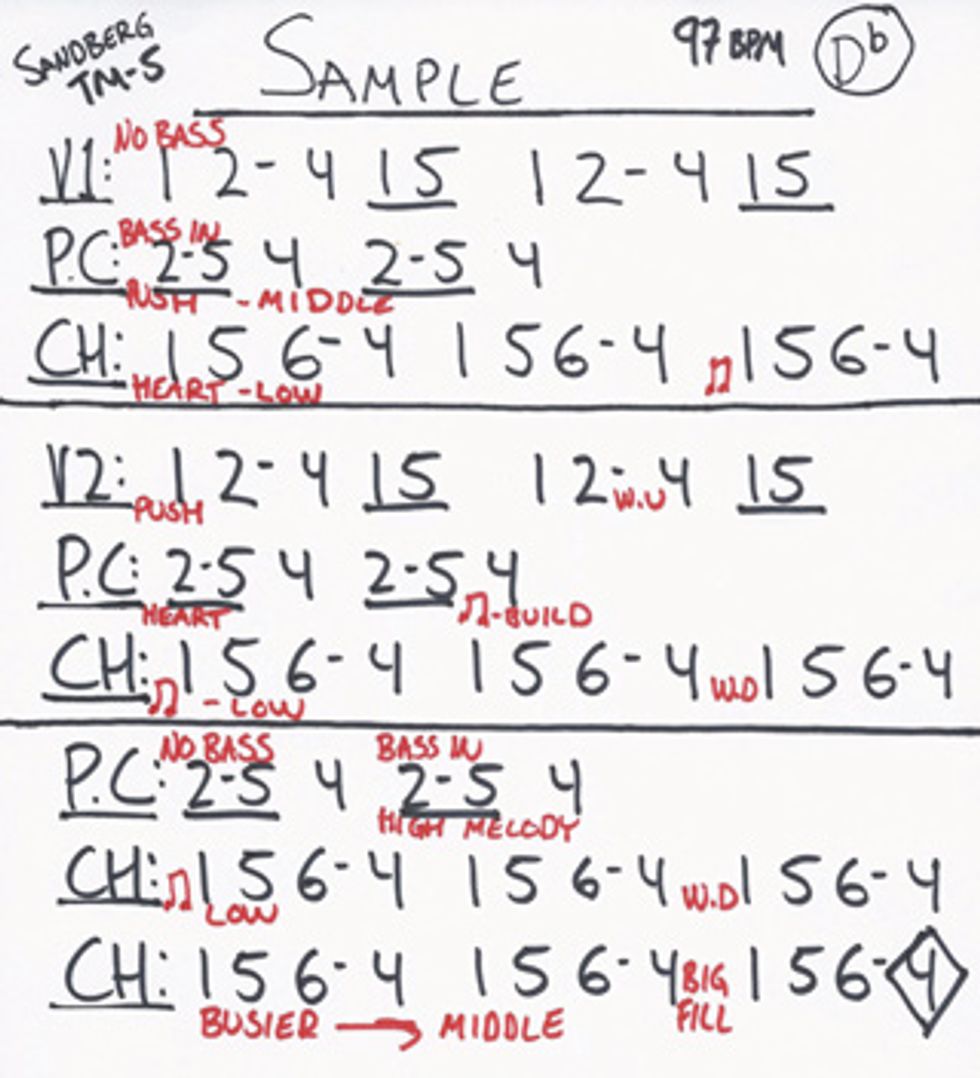

Writing a clear chart with your own music-shorthand notes around the chords will enable you to play confidently without really knowing a particular song.

During my years playing in bars, I would often go out to watch friends play on my nights off and inevitably get invited onstage to sit in and play with them. But when you sit in with a band to play songs they know—songs you might not be familiar with—the situation can get hairy quickly. On the occasions I’d tell my friends that I wasn’t too familiar with a song, they’d always say: “Man, you have great ears, you’ll be able to follow, no problem.”

Herein lies the problem: As a bassist—when playing an actual song (not just jamming)—we can never follow! Our primary job is to always lead, and lead confidently. We can’t wait a millisecond and come in on the second eighth-note of a bar if we are unsure of the changes, and “get by” like a guitarist or keyboardist is able to do when they aren’t 100 percent sure of what they are doing. That latency and attitude is just not a luxury afforded to us bass players. In almost every genre of music with a set song form, we will set up the next chord with a bass line or a walk leading into it. Other players are supposed to be able to follow us. We set up chord changes like drummers set up sections of a song with fill. It is one of our primary functions. We always have to be first on the scene.

To be able to do this with confidence on every chord change and arrangement twist—even without truly knowing the song in question—you need to really refine your note-taking skills so you can perform a given song after hearing it only once or twice. By doing this, you will be able to grasp the broad strokes of a song and nail a few of the details without the luxury of adequate time to really learn the particular song. And I am not only talking about the number system we use here in Nashville. (If you are interested, there are several books and articles that explain the Nashville Number System very well.) I am talking about the notes around the chords. The system I use for these notes is very personal and the purpose of this column is to share examples of how I use it. Hopefully, you will be inspired to use whatever symbols or words that best enable your brain to recall the information in the absolute quickest way. So feel free to make up your own shorthand.

Section length. For starters, I label every section (verse, pre-chorus, chorus, bridge, etc.) on my chart or “cheat sheet” on the left-hand side of the page and underline them. By doing this, I’ll clearly know where sections begin and end, which enables me to confidently lead the band into the next section.

Rhythmical pattern. Right under the name of the section will be my “groove indicator.” This is of tremendous importance, since it’s very common in popular music to have different kick-drum and bass patterns from section to section. For example, if the kick-drum hits are on beat 1, on the and of beat 2, and on beat 3, I write “heart.” This is short for heartbeat, which is slang for perhaps the most common kick-drum pattern ever. The next section may have steady eighth-notes—most often seen in choruses— so I will write two eighth-notes in front of the section on my sheet. Another very common pattern, especially for verses, is the kick drum on beat 1 and the and of beat 2. I call it “push groove” and label it “push.”

Range/neck location. As a bassist, the octave placement of a section is a very important element in making one section “pop” from another, and I have three very general octave descriptions: low, middle, and high. I use these terms to describe exactly where on the neck a particular part is played. For example, a song in the key of E might have the verse based around the E located on the 7th fret of the 3rd string, while the chorus of the same song might drop down to the open E on the 4th string.

Signature line direction. For those signature walk ups or walk downs that occur in many songs, I simply write “W.U” or “W.D” on my chart. Doing this helps tremendously with giving direction to the chord progression in the spots where people expect to hear it. I play a fair amount of country/pop, so these two abbreviations show up a lot on my sheets for that genre.

Amount of notes. To direct me to the correct liveliness, or amount of notes in a bass line, I use a different terminology. For example, the last of the double choruses in a song may have a busier bass pattern, so I comment “busier” under that line of chords. During breakdowns, the bass will often add some melodic content played above the 12th fret. If you are learning a song quickly, the term “high melody” will get you in the ballpark without having to learn all the high, solo-like notes in that section note-for-note.

In order to use this technique efficiently, good ears are required. That said, the people that gave you the song to check out just 10 minutes earlier will think you have amazing ears when they hear you play it. Once you start coming up with your own shorthand and “cheat” notes, you can plow through a lot of material very quickly, while still staying true to the recording in many of the important areas. Developing an efficient notation technique is no replacement for learning to read and write music properly, but it’s still a very necessary and fun tool.

Victor Brodén

Victor BrodénNashville bassist and producer Victor Brodén has toured and recorded with more than 25 major-label artists, including LeAnn Rimes, Richard Marx, Casting Crowns, and Randy Houser. His credits also include Grammy-winning albums and numerous television specials on CMT and GAC, as well as performances on The Tonight Show and The Ellen DeGeneres Show. You can reach him at vbroden@yahoo.com.