Interview: Anders Osborne - Feedback, Overtones, & Jagged Electricity

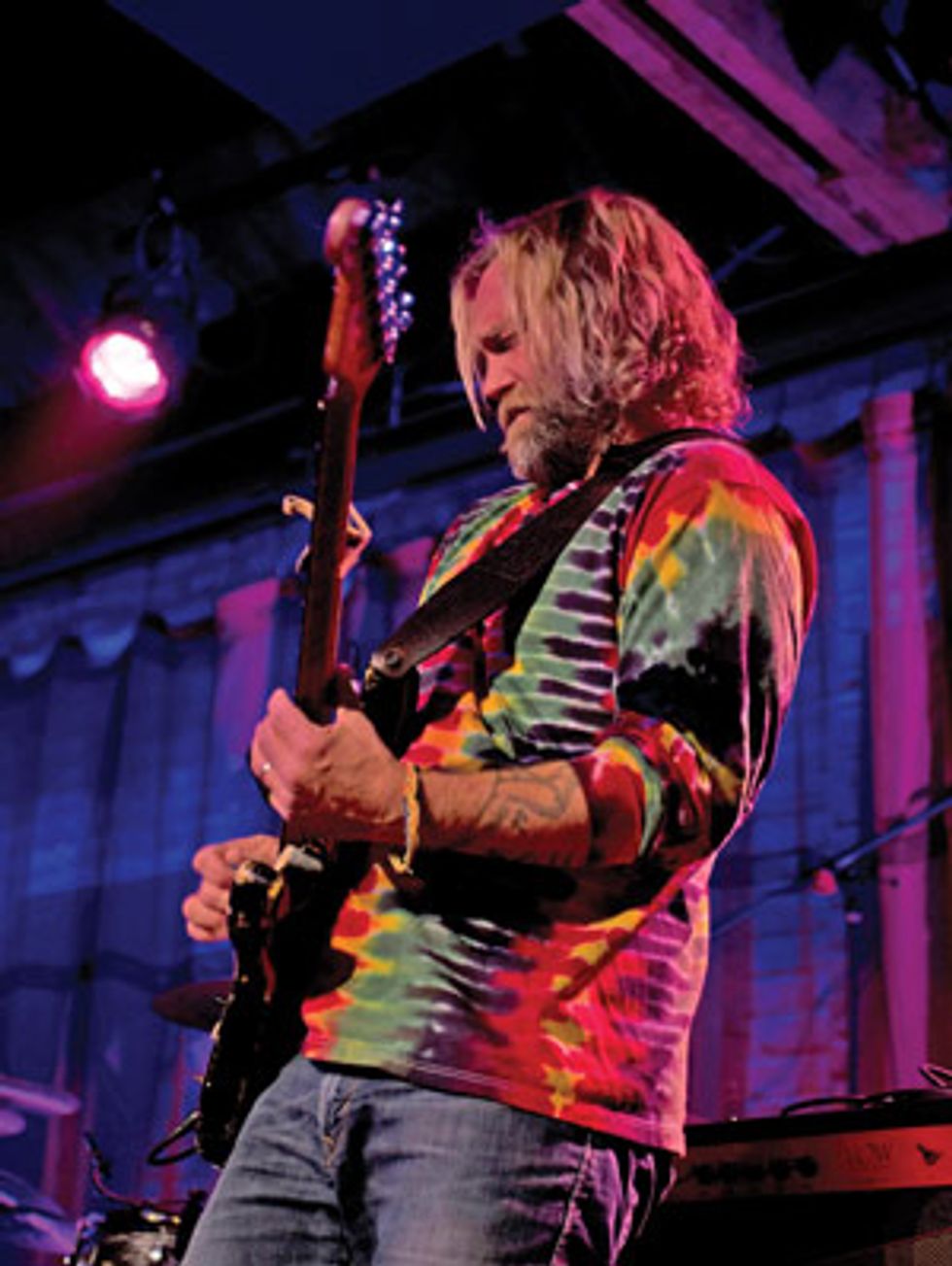

Furious slide-wielding Swede Anders Osborne talks about conquering his demons, taking time with solos, and reconciling his electric live persona with his considerable singer-songwriter skills.

Photo by Jayne Tansey-Patron

Given the fact that he was born in Uddevalla, a city on the southeastern coast of Sweden, you’d hardly expect Anders Osborne’s voice to be flecked with a Cajun twinge. Things are not always what they seem with the 45-year-old singer-songwriter/guitarist—but that’s probably to be expected, considering he and his acoustic guitar spent his late teens traveling everywhere from the former Yugoslavia to France and Israel before coming to the United States and settling in New Orleans almost 30 years ago.

“When people ask why I sound like I’m from New Orleans, I tell them it’s because that’s where I learned to speak English,” he explains. It’s also where he began his music career in earnest, first by busking in the French Quarter, and then building up a following in local clubs. “I had no dreams or visions of where my music would go at first,” he says. “I was just playing on the streets. But then things slowly happened.”

Osborne eventually signed to a small New Orleans label, Rabadash, and made his recorded debut in 1989 with Doin’ Fine. Throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, he released a series of critically well-received albums that combined his love for rock, jazz, blues, folk, country, and roots music, and also made a name for himself as a professional songwriter—most notably as cowriter of Tim McGraw’s 2003 country hit “Watch the Wind Blow By.”

But the last few years have seen a distinct shift in Osborne’s sound. His most recent records—2010’s American Patchwork and the new and excellent Black Eye Galaxy—continue to feature his characteristic mix of hummable acoustic and electric numbers, but the electric-guitar based songs are now decidedly brawnier and infused with layers of squalling 6-string work, much of it on slide. Osborne credits this stylistic shift to several factors, including a change in attitude and perspective following a drawn-out and hard-won battle with substance abuse. But it’s also because his records are now a truer reflection of his live shows, which have always been heavily focused on his guitar playing.

On a broader level, it can perhaps be said that Osborne’s sonic progressions are the consequence of a lifelong restless spirit. When he made the decision as a teenager to leave his home in Sweden, he recalls, “I remember waking up on a Tuesday and saying, ‘I have to get the [expletive] out of here. I can’t stay another minute.’ And on Thursday I hitchhiked out.” Likewise, when it comes to music, he says, “I’m still searching all the time for things to inspire me. For most people, the stuff you listen to when you’re 10 to 14 years old, that tends to be the only music you really ever purely love. After that, you just analyze and criticize. You’re constantly comparing to your first musical impressions. I’m trying to step out of that as much as I can. I’m still trying to find that next thing.”

Photo by Jerry Moran

You pull from numerous American

music styles. As a native Swede who’s

lived all over the world, do you feel that

approaching these genres from the perspective

of an outsider has had an effect

on how you interpret them?

That’s an interesting thing and I’ve thought

about it before. As far as considering my

own origins in terms of the type of music

I play, the truth is I don’t really know how

it fits together. If I were to speculate, I’d

simply say that if the language of music

is something that comes naturally to you,

then you don’t separate things very much.

You know your geography, you know where

you’re from, but stylistically you don’t consider

that at all as you’re taking in influences.

Me being a musician—as opposed to,

say, an author or a carpenter or something

like that—what I do is I interpret the language

of music. That’s the world I’ve always

been in. When I heard Robert Johnson

at a certain age, it did something to me.

When I heard ZZ Top or Kiss or Sweet, it

did something else to me. Then later on

it was John Coltrane, Neil Young, Dylan.

You bring them all in and then you start to

eliminate the ones that don’t stick. What

remains becomes your language.

Black Eye Galaxy is your most assertive

and guitar-centric record to date. You

employ a lot of distorted tones, and several

of the songs feature extended solos.

What led you in that direction?

I think partly it was coming to an understanding

of what I do well. As I’ve changed

my spiritual path and stopped abusing

myself mentally and physically with the

other stuff, everything cleared up a little bit.

You recognize what you’re good at and what

feels good. It’s become more and more evident

to me over the last few years. I think

it started with American Patchwork, where

Stanton [Moore, drums] brought out a lot

of small details in my playing. One of those

was to really distort and crank the guitars

in the way he perceives I do it onstage.

He said, “Let’s work on your tone so that

you don’t get too sweet and too cutesy on

the record.” We just kind of developed a

sound. I hadn’t done that since the mid

’90s, which was the last time I had a big

guitar rig. From doing that and gaining a

better understanding of what I liked—and

also what people responded to in the live

show—when it came time to make this

record, I made sure I had material that

would work well onstage.

Photo by Paul Natkin

To what extent are the new solos improvised—especially on the 11-minute

title track?

The whole middle section of the title track

is all improv. We just worked out what

would serve as home base—where we’d

come together on a riff or a line—and

then go on to the next part. We were all

playing together in the studio, and we’d get

to a certain point in the song and just look

at each other, nod, and start the count

off for everyone to go into a lick together.

Then we’d go on to the next improvisation.

I think there are three home bases in

that song, and having those frees you up.

You know that, whenever you’re through

saying what you need to say, everyone will

come together.

This record is very Neil Young-like in the

sense that your acoustic work is often

quite clean and exacting, while your

electric playing is more ragged and

unorthodox.

I can see that. Neil is definitely an influence

in terms of that wandering approach

on electric. I like to have that element of

searching and taking your time. You start

with something melodic and then keep

building and taking the improvisation

further out, gathering feedback and overtones

and the jagged things going on in

the electricity. You explore. I like that in

Neil and I love that in Coltrane.

A lot of the new lyrics are pretty direct

rather than flowery or metaphorical.

On “Mind of a Junkie,” in particular,

you paint a stark self-portrait. Is it difficult

to be so self-critical?

When I first started working out the lyrics,

it was a completely different thing: I

was sketching ideas around the melody,

and I liked the chorus I had—I felt it

gave the song a real lift, and I thought it

could be really beautiful and powerful.

But then my wife heard it and she said,

“That’s not how you feel. Why don’t

you just write down how you actually

feel.” She was basically saying, to use

your term, that it was too flowery. It

seemed poetically put together. A lot of

bullshit lines. And that triggered me. I

said, “Okay, I’m going to write exactly

how it works when I’m not doing good.”

And once you start doing that, it’s almost

addictive in and of itself. It’s like working

your own program, 100 percent. You’re

just letting it all out. It’s a great exercise

and I highly recommend it to anybody.

But there are definitely nights I play that

song that are a little bit uncomfortable.

Osborne’s Category 5 VOW signature

4x10 combo (left) and 1900 head driving a

4x12. Photo by Paul Natkin

You have an unorthodox guitar style:

You play with a pick, but you occasionally

hit notes with a finger on your

picking hand. How did you develop

that approach?

I think it was unconscious—it just

evolved. At some point I realized there

were certain runs and things I wanted

to do faster, and I couldn’t quite get to

the notes quick enough with just a pick.

So I just started grabbing them with a

finger. It especially helped that I tend to

use open tunings. Open tunings are great

when you’re soloing, because they open

up the fretboard—you can go across the

strings as much as do the vertical scale

thing. You play horizontally a lot more.

So I’d hold down a chord formation and

just drill it with my fingers. With a pick,

for me, the movement almost comes

more from my shoulders. With my fingers,

I can move much more effortlessly.

His main Strat has a ’68 body, an ebony-topped ’80s neck, and stock pickups except for the middle unit, which has recently been switched from a Duncan Hot Rails to a stacked humbucker. Photo by Paul Natkin

Do you mostly play in open tunings?

It comes and goes. Right now, I’m about

50/50—but it used to be 90/10 in terms

of open tuning versus standard.

What tunings do you favor?

Open D, for the most part, because it

gives me some nice low end. There are

a bunch of open D songs on the new

record: “Send Me a Friend,” “Black Tar,”

“Black Eye Galaxy”….

… A lot of the heavier material.

Oh yeah. I put on real heavy strings, .013–

.054s, and raised the action, so there’s big

tone. That helps with the slide, as well.

Onstage, you’re never without a slide—you switch between slide and fretting

notes pretty seamlessly.

It’s a comfort thing for me to have the

slide on the pinkie. Even if I don’t need

it—and I could certainly use that extra

finger sometimes—it’s almost a little

security blanket. It’s like, if I have an

open tuning and a glass slide, all of a

sudden I feel safe.

Which specific players influenced your

slide work?

In my early years, certainly Ry Cooder.

He doesn’t play heavy, but he plays a different

kind of heavy. That’s one of the

debates I had with Stanton—that, a lot

of times in the past, I had been a little

too tongue-in-cheek and comical in my

slide approach. Doing those fun, cool

little licks. Live, I would play really heavy,

with a really big tone, but on my records I

would always bring it back into Ry Cooderland.

That’s stopped now.

Anders Osborne's Gear

Guitars

Fender Strat with ’68 body, Fender 1962 Strat reissue, Fender 1957 Strat reissue,

Gibson Les Paul Standard goldtop with P-90s, 1959 Gretsch 6118 Double

Anniversary, 1966 Guild Starfire V, 1969 Martin D-18, 1963 Gibson B-25, 1961

Gibson J-45, custom McAlister flattop, Yamaha AC3R, Yamaha CPX1200

Amps

Category 5 signature VOW, Category 5 1900 models

Effects

D’Addario .011–.052 sets, D’Addario .013–.054 sets (for ’68 Strat tuned to open

D), Planet Waves 1mm picks, handmade bottleneck slide (“Preferably from Italian

wine bottles—they have a warmer and denser tone”), 1972 handmade custom

black leather strap with caveman imprints, TC Electronic PolyTune, Morley ABY

pedal, Planet Waves cables

Tell us about your primary stage guitar—the black Strat that looks like it’s been

put through the ringer.

[Laughs.] Yeah, I got that guitar in 1986,

and it’s a mix of things: It has a ’68 body

and what I believe is an early-’80s custom

bird’s-eye maple neck, with an African

ebony fretboard. There’s a metal pickguard,

and there used to be a Seymour Duncan

Hot Rails pickup in the middle position

but I swapped it out and put a stacked

humbucker in there. The other pickups

are stock. It’s banged up, and there’s a tone

knob missing at the moment, as well.

So it’s something of a mutt.

It is. It was already modified to how it is

now when I got it, except for that middle

pickup. I saw it at a music store in New

Orleans and the guys working there didn’t

even know what it was. So they charged

me 170 bucks for it. But it’s an interesting

guitar. It’s not even originally black. You

can see that it had this beautiful, creamy

sunburst finish that was just painted right

over. Somebody messed it up real good, but

it’s perfect for me—I love it—and it’s been

my main guitar ever since.

YouTube It

Listen to the jagged electric

blues coming out of Osborne’s

“mutt” black Strat as he employs

his unorthodox picking

style at 4:30.

This performance at The

Independent San Francisco

showcases Osborne improvising

to find the groove with drummer

Stanton Moore’s band.

Osborne unleashes his inner Cajun

Swede on “Louisina Gold”

from his latest album, Black

Eye Galaxy.