The rockabilly guitarist of The Head Cats and Lonesome spurs talks recording with Lemmy, James Trussart guitars and keeping it simple.

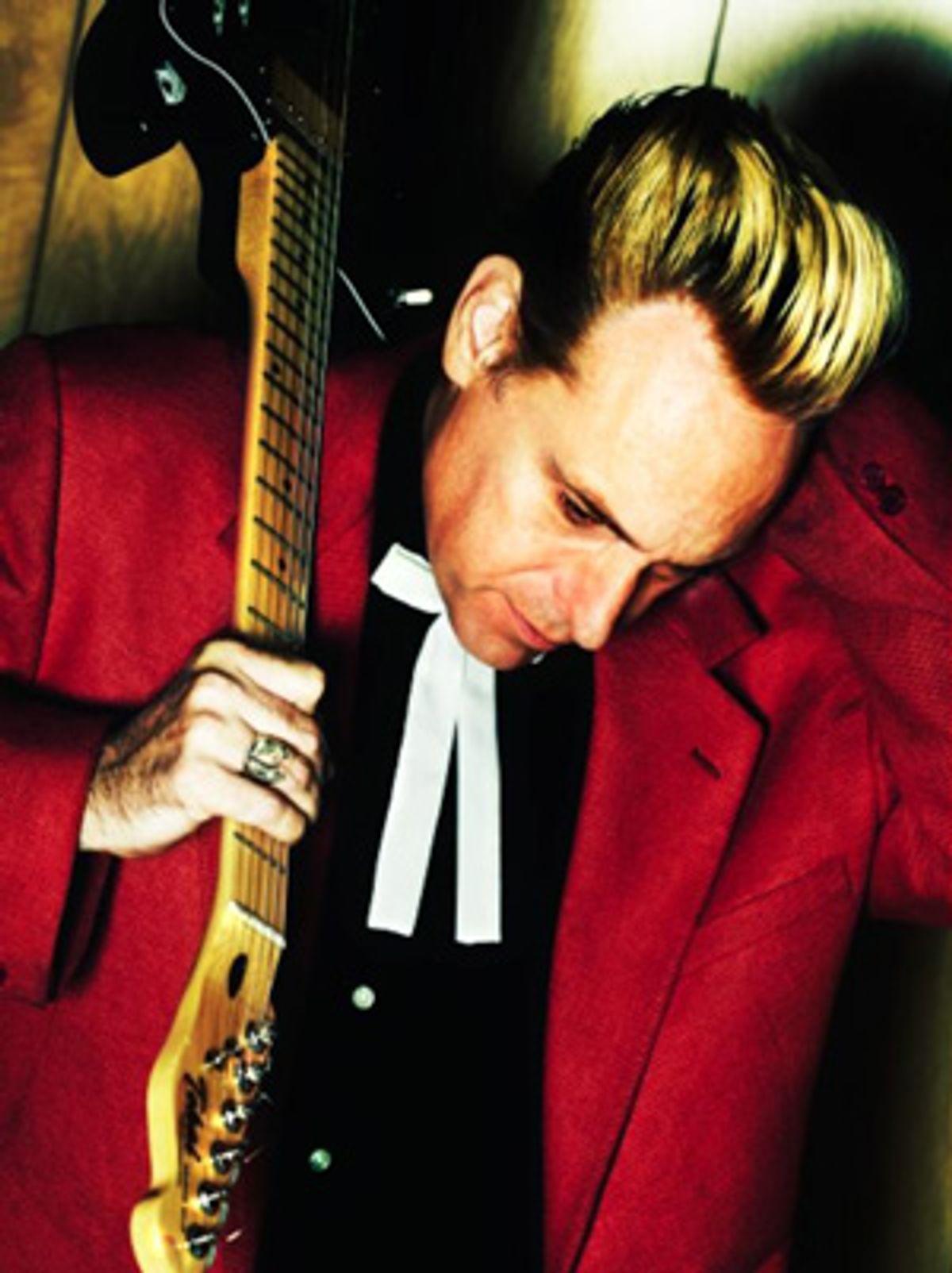

Danny B. Harvey is a guy you should know. He’s a guitar industry staple—his red jacket, pompadour and rockabilly riffs grace the James Trussart booth at NAMM each year. But booth riffs are just a footnote in Harvey’s diverse and impressive career. The Joe Pass-taught guitarist has played some of the biggest names across the spectrum of music, including Lemmy, Johnny Ramone, Nancy Sinatra, the Stray Cats, Levi Dexter, Eric Johnson, Brian Setzer, Wanda Jackson and was half of the Lonesome Spurs duo that paired him with Lynda Kay Parker [featured in the May issue of Premier Guitar]. But no matter who he works with or what style of music he’s playing, Harvey lives by a minimalistic mantra: keep it simple.

Harvey stays true to this mantra with his playing style and his gear. When it comes to his playing, Harvey compliments each song with the tastiest of licks, delivered with a hybrid style that mixes flatpicking and fingerpicking. Despite his formidable chops, he never overworks the guitar or overpowers the song. When it comes to gear, Harvey prefers to let the organic relationship between the amplifier and guitar do the talking. To his ears and fingers, the voice of a good soundin’ guitar and a cranked amp is the language of impeccable tone.

We recently caught up with the busy Lonestar guitar slinger after he finished the newest Head Cat album with Lemmy and Slim Jim [Stray Cats]. We talk with Harvey about Merle Travis fingerpicking, Head Cat soundchecks and recording in the shower.

What is your earliest memory of the guitar?

I started fooling around with the guitar around the age of 10—it was just something I did but had no clue what I was doing [laughs]. I’m left-handed so I used to pick up guitars and turn them upside down and tried to play left-handed, but I never really learned anything because I was never taught or restrung the guitar correctly. But when I was 13 years old I was living in Kentucky and my next door neighbor who was ‘bout 17 or 18 years old—the way I remember it he was a really good guitarist—knew how to play all the Zeppelin and Hendrix songs I had heard on the radio. He had a few guitars so we’d just hang out and he started to teach me to play familiar radio rock songs, but the first song I learned all the way through was “Purple Haze.” And because all of his guitars were right-handed, that’s how I learned to adjust and play right-handed. From learning those first riffs in Kentucky, I played guitar for hours every day then on.

While it sounds like you had a rock ‘n’ roll start to guitar-playing, you currently play more of a traditional rockabilly and country style of guitar. How did you make that transition?

Well, I grew up in the south in rural areas. I was born in Texas and then moved to Kentucky and my dad only played country music. But when I was a teenager I was never a really big fan of country—I didn’t dislike it, but I had no idea until later how ingrained in me it was [laughs]]. Once I was about 14 years old I became the best guitarist in Catlettsburg, Kentucky, [laughs] so I started playing with 40-year-old men and most [of] their gigs were country-style gigs. So at that time I would play country to make money, but I still played rock when I was at home or just hanging out.

We moved to California when I was 16 years old to another rural area north of L.A. and I really got into jazz because I was taking private lessons from Joe Pass. But what really got me into rockabilly was that it was the only style of music I could play all my jazz, country and rock licks. Most of the rockabilly stuff is 12-bar progression and if you get jazzy you can take it to swing and western swing or if you want you can get bluesy with it or just go towards country.

And how did that evolve into a career as a go-to rockabilly guitarist?

When I was in high school, Levi and the Rockats came over from England and I went and saw them perform in L.A. I just really liked how they took it all the way—they had the clothing, the hair and the ’50s swagger. And by this point I had began playing rockabilly but I was still just a normal teenager from L.A., but the way they embraced that whole ’50s style really struck a chord with me. Back then, there were no younger bands with greasy, slicked back hair and at one of their shows I was asked by their manager to go backstage and meet them because they liked meeting young Americans that were into the ’50s thing, too.

I went down to another Levi and the Rockats show that was on Christmas Day and when I got there they said they had just fired Levi and were looking for another guitarist and asked me to join. Then, I go into the dressing room and Levi tells me he just quit the band and was going to start a new band back in England and asked me to be his guitarist. I wanted to go to England so I decided to go with Levi and that’s when we started Levi Dexter and the Ripchords.

It’s hard enough for a young and unknown guitarist to get one job offer, but you got two within five minutes!

[laughs] And thankfully it all worked out. But ironically, after two years of performing with Levi, I left the Ripchords and started working with the Rockats—who had always kept in contact with me once I left for England. So I ended being in both bands after their split. A few years ago, they did a Levi and the Rockats reunion show and they asked me to play guitar because they lost touch with the original rhythm guitarist. Levi was like, “Well, you played in the Rockats and you played in Levi and the Ripchords so it only makes sense that you’re in Levi and the Rockats.”

For a guy that plays all styles of music and guitar, who are some of your favorite guitarists?

Whatever genre of music it is, all my favorite guitarists come from the ’50s. For jazz I really love Kenny Burell, even though my favorite record of his is Midnight Blue from 1963. For rock ‘n’ roll, I really love Cliff Gallup’s work with The Blue Caps and James Burton, and for the more rockabilly and country stuff I tend to favor Grady Martin, Merle Travis and Chet Atkins. Those guys are on the top of my list of favorite guitarists and they all came from or started in the ’50s. I mean, I love Jeff Beck a lot but his older stuff was drawing from that same pool but he took it to another level.

I can definitely hear the Merle Travis and other finger-picking country influences with your Lonesome Spurs work—particularly in songs like “Lonesome Spur Stomp” and “Ride Straddle Saloon.”

I can definitely hear the Merle Travis and other finger-picking country influences with your Lonesome Spurs work—particularly in songs like “Lonesome Spur Stomp” and “Ride Straddle Saloon.”

Merle Travis is hands-down my favorite guitarist. He’s definitely the reason that I use a thumbpick and do a lot of flatpicking things using the side of the thumbpick and fingerpicking things. With the Lonesome Spurs, because Lynda Kay would play rhythm guitar and kick the suitcase—there’s not much you can do with a suitcase bass drum (enclosed inside an old red Samsonite suitcase)—so it was like playing with a click track [laughs]. She would just play straight quarter notes on everything—even when she’s strumming the guitar. It was great because I could do all my Merle Travis-style riffs and rockabilly riffs at breakneck speed because she was holding down the tempo and there’s nothing that gets in the way. So when I’d come up with licks, intros or solos for the Lonesome Spurs I would always approach it by thinking of the wildest part I could fit into the given song.

And the “Lonesome Spur Stomp” was like a fingerpicking riff … a warm-up type of thing I had written and played around with already. I just laid down a click track with her suitcase bass drum—because she didn’t record that part, but she plays the drum live—and went to town.

Players often overlook the different picks and playing styles. Explain how you incorporate several picks and playing styles.

When I was young I always flatpicked and I started using my fingers when I was taking lessons with Joe Pass. He specifically told me during one of my lessons to stop using the pick and rely more on my fingers because you could do so much more with chords. So during my time with the Rockats and all throughout the ’80s I’d always put the pick in my mouth, then fingerpick and then use a flatpick to play rhythm. Also, when were putting the Ripchords together I took a year at USC as a Classical Guitar major and took a course with Pepe Romero, and that helped me really excel at fingerpicking. It wasn’t until the early ’90s that I really started studying Merle Travis and forcing myself to use a thumbpick. I use to buy those old Dunlop thumbpicks and file them down—which a lot of people did—so I had a little more control over them, but now Fred Kelly in Nashville makes these Slick picks. I just basically evolved as a thumbpicker so I didn’t have to keeping putting and taking the pick out of my mouth.

For the Lonesome Spurs record, what was your signal chain?

At that time I had a lot of amps, but I believe I mainly used an Ampeg Reverbojet combo. We recorded up in my studio in Aqua Dulce, California, and I had this really nice, but completely DIY-setup. There was a bathroom connected to the studio and all it had in it was a shower, so I put the amp in the shower and mic’d it about four feet away and I had the guitars sitting by me in the control area. For the “Lonesome Spur Stomp” I used two guitars to record it—a James Trussart Steelcaster (Tele-style) and a 2000 Les Paul Raw. But after playing it back I just used the track with James’ guitar because it was a little bit brighter.

How did you get turned on to Trussart’s guitars?

I was first drawn to his guitars aesthetically at a guitar show where they were just hanging up. They looked like pieces of art rather than musical instruments. He was hanging around so I met him and we hit it off so well that I eventually ended up being his roommate for three years in L.A. During those years I really got to see how much he cared for and nurtured each guitar throughout the building process. He’s built me some guitars since then and he’s tweaked a few specifically for me.

For instance, I’d gig with one of his guitars and I remember the radius of the neck [was] a little too high and wanted it to be a little rounder—he had no problem changing it for me. I really like low action with .010–.046 gauge strings and I really prefer a high, flat neck radius going back to the days when I played all that rock stuff. I liked the lower action particularly for the style of playing and finger-picking I do and the flatter necks because it just feels the most natural in my hands. Lately I’ve been using those Stewart MacDonald Golden Age pickups. It’s nice because Eric, one of my good friends, helps build them. [He] specifically winds some pickups for me that are in a few of my guitars, including a set that he made a little hotter than any of their standard models for my rockin’ guitar.

All of James’ guitars that I own now are perfect—they’ve been fine-tuned to the way I play. And it’s not like he did that for me because I was his roommate, he’d do that kind of thing for anybody. Plenty of touring guitarists swing by when they are in town for fatter frets, hotter pickups or whatever, and James does it all with a smile. He really cares about not only crafting the perfect guitar, but the perfect guitar for each player.

What models of Trussart’s guitars do you currently have?

I currently have three Trussart guitars: A white and red rose engraved Steelcaster (Tele-style) primarily for country, Americana and rootsy gigs; A chrome hollowbody SteelDeville (Les Paul-style) with only one master volume knob and a Bigsby used for the Head Cat stuff because it is super loud and gets some great natural distorted tones; and the third one is a black hollowbody SteelDeville—with a red star for Texas—that is in between those two. It has a really great clean, jazz tone but if you crank it up and dig in a bit you can get some gnarly blues and rockabilly tones with it, too. That red star SteelDeville is the one I probably use the most, including when I record.

How did you meet Lemmy and Slim Jim [Stray Cats] and start The Head Cat?

Slim Jim and I were first friends when I was 17 years old over in England playing with the Ripchords. The first rendition of Levi and the Ripchords had Brian Setzer as the other guitarist and his brother Gary was the drummer. They both passed on the Ripchords because their band was starting to take off. A few months later in London I met Jim with his new band the Tomcats. Since then, Jim and I have always stayed in contact and we were in a band called The Swing Cats with bassist Lee Rocker [Stray Cats] that put out two albums. In 2000, Lee was doing his solo stuff, so Jim and I were asked to do an Elvis tribute album so we contacted all these artists and let them [do] each song the way they wanted to do it. We got Johnny Ramone, Lemmy and a few other friends to be on the record. We did “Good Rockin’ Tonight,” “Stuck on You” and “Viva Las Vegas” with Lemmy. And when we went to record his part for “Viva Las Vegas” he said “it’s not fast enough and it’s in the wrong key.” So he picks up an acoustic and tells me to get on bass and suggest that we record a few of the songs as a trio. We ended doing the last two songs as a trio.

It was just a good, smooth process and at the end Lemmy mentioned that we should do a whole album as a trio. So we approached the record label, they agreed to it, and we recorded Fool’s Paradise. After the album was released we were approached to do a live DVD and so we did that, too, and we just have a great time playing these songs together that we’ve been doing more and more shows when we’ve all had the time.

How’s the second Head Cat album coming along?

The album is completely recorded and finished. We did two songs last year and then we took three more days this year and recorded four each day and mixed it on the third day. Lemmy, Jim and I have been playing together for 10 years, so we’re pretty quick and efficient at what we do now. Right now we’re trying to figure out what label to put it on and how to promote it because we were disappointed with how the first album was promoted.

How did you guys decide on the songs you’d cover this time?

Well, this time we actually did two original songs—one that Lemmy wrote—and the others were songs we’ve played around or did live. The reason this band works for Lemmy—obviously Motörhead is his real band—is because it’s just for fun and we never have band meetings or songwriting sessions. Three of the songs that we did were happened while we were in the studio and talking music and we’d pull up YouTube and check out the song, find out how to play it and within an hour of learning them we’re recording the tracks.

What is the Head Cat approach to covering songs?

The way we play with The Head Cat kind of defines the sound of whatever song or style we cover. You’re going to have Lemmy playing his bass through his Marshall stack, which means when we play live I’ll have to play through something just as loud and distorted to compete with him. For my playing style, I tend to go towards Johnny Thunder or more of a punk rock vibe with big power chords with plenty of double stops and not too much jangly stuff. We pretty much learn the chords and turn everything up to max volume [laughs] .We played the Beatles’ “You Can’t Do That” on this record and Lemmy doesn’t play bass anything like McCartney so he came up with his own bass line, which dictates the kind of rhythm guitar I can play. I play George Harrison’s riff, but I didn’t have a 12-string so I doubled it an octave higher and had the producer put it together at the beginning to sound like a 12-string Rickenbacker.

With all your projects and working with stars like Lemmy and Nancy Sinatra, what is the dynamic like when you’re working?

It’s been said before, Lemmy is rock ‘n’ roll … I can’t disagree with that one bit [laughs]. With Lemmy, what you see is what you get. As a person, he’s one of the nicest and most genuine people you’ll ever meet. It’s funny … he’s just so loyal to The Head Cat when he’s got so many other things going on around him. With who he is, he could easily throw his weight around in the studio or on stage—and it’d be typical—but it’s always a three-way decision on all things.

And with Nancy she would never call me Danny—she’d always call me Dan. She asked me when we first met if it’d be OK if she called me Dan because when she heard Danny she thought of boys. I told her I didn’t mind at all … but the only other person that calls me Dan is Lemmy.

To best describe the guitar tone from the first Head Cat album, I’d say it’s unruly, loud and completely rockin’. What is your typical setup for a Head Cat set?

A lot of our shows are one-offs or somewhere that we fly in, play a few shows and then leave so I generally request a 100 watt Marshall half stack. I’ve also used some Fender Hot Rod Devilles and turned them up as loud as they’ll go. This is the only gig that during soundcheck I turn my Marshall up almost to 10 and hit a couple chords and the sound man always gives me an OK sign and says, “Sounds great.” Any other gig I use much smaller amps and they always tell me I’m a little loud on stage and to turn it down a bit. With The Head Cat, no matter how loud it is, they always say, “Sounds great.”

We here at PG believe in the “relentless pursuit of tone,” what do you think makes up a good tone?

It is so hard to describe sonically what good tone is but I know it when I hear it. I really like when you hear a guitar tone that talks to you like a human voice as opposed to an electronic guitar. Over the years, I’ve come to the conclusion that a lot of that is in a player’s fingers and not the electronics. People like B.B. King can play any guitar and it’ll still sound like B.B. King, but plenty of people have Lucille replicas and don’t sound anything like him. Also, in a lot of the guitar tones I like there aren’t many effects between the guitar and the amp. I never got the idea of having vintage guitars and amps, but then have like 15 pedals between them [laughs]… that can’t possibly be that vintage tone those guys are looking for.

Danny B. Harvey’s Head Cat Gear

Guitars

James Trussart Rusty Steelcaster

Fender Jazzmaster reissue (owned by Lemmy)

Amps & Cabinets

Zinky Combo

Marshall Murder One duplicate (based on Lemmy’s original vintage JMP Superbass amp)

Fender Hot Rod Deville

Lemmy Kilmister Signature 1992LEM Super Bass Head

Marshall 4x12 (Celestion Vintage 30s)

Effects

None

Harvey stays true to this mantra with his playing style and his gear. When it comes to his playing, Harvey compliments each song with the tastiest of licks, delivered with a hybrid style that mixes flatpicking and fingerpicking. Despite his formidable chops, he never overworks the guitar or overpowers the song. When it comes to gear, Harvey prefers to let the organic relationship between the amplifier and guitar do the talking. To his ears and fingers, the voice of a good soundin’ guitar and a cranked amp is the language of impeccable tone.

We recently caught up with the busy Lonestar guitar slinger after he finished the newest Head Cat album with Lemmy and Slim Jim [Stray Cats]. We talk with Harvey about Merle Travis fingerpicking, Head Cat soundchecks and recording in the shower.

What is your earliest memory of the guitar?

I started fooling around with the guitar around the age of 10—it was just something I did but had no clue what I was doing [laughs]. I’m left-handed so I used to pick up guitars and turn them upside down and tried to play left-handed, but I never really learned anything because I was never taught or restrung the guitar correctly. But when I was 13 years old I was living in Kentucky and my next door neighbor who was ‘bout 17 or 18 years old—the way I remember it he was a really good guitarist—knew how to play all the Zeppelin and Hendrix songs I had heard on the radio. He had a few guitars so we’d just hang out and he started to teach me to play familiar radio rock songs, but the first song I learned all the way through was “Purple Haze.” And because all of his guitars were right-handed, that’s how I learned to adjust and play right-handed. From learning those first riffs in Kentucky, I played guitar for hours every day then on.

While it sounds like you had a rock ‘n’ roll start to guitar-playing, you currently play more of a traditional rockabilly and country style of guitar. How did you make that transition?

Well, I grew up in the south in rural areas. I was born in Texas and then moved to Kentucky and my dad only played country music. But when I was a teenager I was never a really big fan of country—I didn’t dislike it, but I had no idea until later how ingrained in me it was [laughs]]. Once I was about 14 years old I became the best guitarist in Catlettsburg, Kentucky, [laughs] so I started playing with 40-year-old men and most [of] their gigs were country-style gigs. So at that time I would play country to make money, but I still played rock when I was at home or just hanging out.

We moved to California when I was 16 years old to another rural area north of L.A. and I really got into jazz because I was taking private lessons from Joe Pass. But what really got me into rockabilly was that it was the only style of music I could play all my jazz, country and rock licks. Most of the rockabilly stuff is 12-bar progression and if you get jazzy you can take it to swing and western swing or if you want you can get bluesy with it or just go towards country.

And how did that evolve into a career as a go-to rockabilly guitarist?

When I was in high school, Levi and the Rockats came over from England and I went and saw them perform in L.A. I just really liked how they took it all the way—they had the clothing, the hair and the ’50s swagger. And by this point I had began playing rockabilly but I was still just a normal teenager from L.A., but the way they embraced that whole ’50s style really struck a chord with me. Back then, there were no younger bands with greasy, slicked back hair and at one of their shows I was asked by their manager to go backstage and meet them because they liked meeting young Americans that were into the ’50s thing, too.

I went down to another Levi and the Rockats show that was on Christmas Day and when I got there they said they had just fired Levi and were looking for another guitarist and asked me to join. Then, I go into the dressing room and Levi tells me he just quit the band and was going to start a new band back in England and asked me to be his guitarist. I wanted to go to England so I decided to go with Levi and that’s when we started Levi Dexter and the Ripchords.

It’s hard enough for a young and unknown guitarist to get one job offer, but you got two within five minutes!

[laughs] And thankfully it all worked out. But ironically, after two years of performing with Levi, I left the Ripchords and started working with the Rockats—who had always kept in contact with me once I left for England. So I ended being in both bands after their split. A few years ago, they did a Levi and the Rockats reunion show and they asked me to play guitar because they lost touch with the original rhythm guitarist. Levi was like, “Well, you played in the Rockats and you played in Levi and the Ripchords so it only makes sense that you’re in Levi and the Rockats.”

For a guy that plays all styles of music and guitar, who are some of your favorite guitarists?

Whatever genre of music it is, all my favorite guitarists come from the ’50s. For jazz I really love Kenny Burell, even though my favorite record of his is Midnight Blue from 1963. For rock ‘n’ roll, I really love Cliff Gallup’s work with The Blue Caps and James Burton, and for the more rockabilly and country stuff I tend to favor Grady Martin, Merle Travis and Chet Atkins. Those guys are on the top of my list of favorite guitarists and they all came from or started in the ’50s. I mean, I love Jeff Beck a lot but his older stuff was drawing from that same pool but he took it to another level.

I can definitely hear the Merle Travis and other finger-picking country influences with your Lonesome Spurs work—particularly in songs like “Lonesome Spur Stomp” and “Ride Straddle Saloon.”

I can definitely hear the Merle Travis and other finger-picking country influences with your Lonesome Spurs work—particularly in songs like “Lonesome Spur Stomp” and “Ride Straddle Saloon.”

Merle Travis is hands-down my favorite guitarist. He’s definitely the reason that I use a thumbpick and do a lot of flatpicking things using the side of the thumbpick and fingerpicking things. With the Lonesome Spurs, because Lynda Kay would play rhythm guitar and kick the suitcase—there’s not much you can do with a suitcase bass drum (enclosed inside an old red Samsonite suitcase)—so it was like playing with a click track [laughs]. She would just play straight quarter notes on everything—even when she’s strumming the guitar. It was great because I could do all my Merle Travis-style riffs and rockabilly riffs at breakneck speed because she was holding down the tempo and there’s nothing that gets in the way. So when I’d come up with licks, intros or solos for the Lonesome Spurs I would always approach it by thinking of the wildest part I could fit into the given song.

And the “Lonesome Spur Stomp” was like a fingerpicking riff … a warm-up type of thing I had written and played around with already. I just laid down a click track with her suitcase bass drum—because she didn’t record that part, but she plays the drum live—and went to town.

Players often overlook the different picks and playing styles. Explain how you incorporate several picks and playing styles.

When I was young I always flatpicked and I started using my fingers when I was taking lessons with Joe Pass. He specifically told me during one of my lessons to stop using the pick and rely more on my fingers because you could do so much more with chords. So during my time with the Rockats and all throughout the ’80s I’d always put the pick in my mouth, then fingerpick and then use a flatpick to play rhythm. Also, when were putting the Ripchords together I took a year at USC as a Classical Guitar major and took a course with Pepe Romero, and that helped me really excel at fingerpicking. It wasn’t until the early ’90s that I really started studying Merle Travis and forcing myself to use a thumbpick. I use to buy those old Dunlop thumbpicks and file them down—which a lot of people did—so I had a little more control over them, but now Fred Kelly in Nashville makes these Slick picks. I just basically evolved as a thumbpicker so I didn’t have to keeping putting and taking the pick out of my mouth.

For the Lonesome Spurs record, what was your signal chain?

At that time I had a lot of amps, but I believe I mainly used an Ampeg Reverbojet combo. We recorded up in my studio in Aqua Dulce, California, and I had this really nice, but completely DIY-setup. There was a bathroom connected to the studio and all it had in it was a shower, so I put the amp in the shower and mic’d it about four feet away and I had the guitars sitting by me in the control area. For the “Lonesome Spur Stomp” I used two guitars to record it—a James Trussart Steelcaster (Tele-style) and a 2000 Les Paul Raw. But after playing it back I just used the track with James’ guitar because it was a little bit brighter.

Danny demos James Trussart's latest for a Premier Guitar video |

I was first drawn to his guitars aesthetically at a guitar show where they were just hanging up. They looked like pieces of art rather than musical instruments. He was hanging around so I met him and we hit it off so well that I eventually ended up being his roommate for three years in L.A. During those years I really got to see how much he cared for and nurtured each guitar throughout the building process. He’s built me some guitars since then and he’s tweaked a few specifically for me.

For instance, I’d gig with one of his guitars and I remember the radius of the neck [was] a little too high and wanted it to be a little rounder—he had no problem changing it for me. I really like low action with .010–.046 gauge strings and I really prefer a high, flat neck radius going back to the days when I played all that rock stuff. I liked the lower action particularly for the style of playing and finger-picking I do and the flatter necks because it just feels the most natural in my hands. Lately I’ve been using those Stewart MacDonald Golden Age pickups. It’s nice because Eric, one of my good friends, helps build them. [He] specifically winds some pickups for me that are in a few of my guitars, including a set that he made a little hotter than any of their standard models for my rockin’ guitar.

All of James’ guitars that I own now are perfect—they’ve been fine-tuned to the way I play. And it’s not like he did that for me because I was his roommate, he’d do that kind of thing for anybody. Plenty of touring guitarists swing by when they are in town for fatter frets, hotter pickups or whatever, and James does it all with a smile. He really cares about not only crafting the perfect guitar, but the perfect guitar for each player.

What models of Trussart’s guitars do you currently have?

I currently have three Trussart guitars: A white and red rose engraved Steelcaster (Tele-style) primarily for country, Americana and rootsy gigs; A chrome hollowbody SteelDeville (Les Paul-style) with only one master volume knob and a Bigsby used for the Head Cat stuff because it is super loud and gets some great natural distorted tones; and the third one is a black hollowbody SteelDeville—with a red star for Texas—that is in between those two. It has a really great clean, jazz tone but if you crank it up and dig in a bit you can get some gnarly blues and rockabilly tones with it, too. That red star SteelDeville is the one I probably use the most, including when I record.

How did you meet Lemmy and Slim Jim [Stray Cats] and start The Head Cat?

Slim Jim and I were first friends when I was 17 years old over in England playing with the Ripchords. The first rendition of Levi and the Ripchords had Brian Setzer as the other guitarist and his brother Gary was the drummer. They both passed on the Ripchords because their band was starting to take off. A few months later in London I met Jim with his new band the Tomcats. Since then, Jim and I have always stayed in contact and we were in a band called The Swing Cats with bassist Lee Rocker [Stray Cats] that put out two albums. In 2000, Lee was doing his solo stuff, so Jim and I were asked to do an Elvis tribute album so we contacted all these artists and let them [do] each song the way they wanted to do it. We got Johnny Ramone, Lemmy and a few other friends to be on the record. We did “Good Rockin’ Tonight,” “Stuck on You” and “Viva Las Vegas” with Lemmy. And when we went to record his part for “Viva Las Vegas” he said “it’s not fast enough and it’s in the wrong key.” So he picks up an acoustic and tells me to get on bass and suggest that we record a few of the songs as a trio. We ended doing the last two songs as a trio.

It was just a good, smooth process and at the end Lemmy mentioned that we should do a whole album as a trio. So we approached the record label, they agreed to it, and we recorded Fool’s Paradise. After the album was released we were approached to do a live DVD and so we did that, too, and we just have a great time playing these songs together that we’ve been doing more and more shows when we’ve all had the time.

How’s the second Head Cat album coming along?

The album is completely recorded and finished. We did two songs last year and then we took three more days this year and recorded four each day and mixed it on the third day. Lemmy, Jim and I have been playing together for 10 years, so we’re pretty quick and efficient at what we do now. Right now we’re trying to figure out what label to put it on and how to promote it because we were disappointed with how the first album was promoted.

How did you guys decide on the songs you’d cover this time?

Well, this time we actually did two original songs—one that Lemmy wrote—and the others were songs we’ve played around or did live. The reason this band works for Lemmy—obviously Motörhead is his real band—is because it’s just for fun and we never have band meetings or songwriting sessions. Three of the songs that we did were happened while we were in the studio and talking music and we’d pull up YouTube and check out the song, find out how to play it and within an hour of learning them we’re recording the tracks.

What is the Head Cat approach to covering songs?

The way we play with The Head Cat kind of defines the sound of whatever song or style we cover. You’re going to have Lemmy playing his bass through his Marshall stack, which means when we play live I’ll have to play through something just as loud and distorted to compete with him. For my playing style, I tend to go towards Johnny Thunder or more of a punk rock vibe with big power chords with plenty of double stops and not too much jangly stuff. We pretty much learn the chords and turn everything up to max volume [laughs] .We played the Beatles’ “You Can’t Do That” on this record and Lemmy doesn’t play bass anything like McCartney so he came up with his own bass line, which dictates the kind of rhythm guitar I can play. I play George Harrison’s riff, but I didn’t have a 12-string so I doubled it an octave higher and had the producer put it together at the beginning to sound like a 12-string Rickenbacker.

With all your projects and working with stars like Lemmy and Nancy Sinatra, what is the dynamic like when you’re working?

It’s been said before, Lemmy is rock ‘n’ roll … I can’t disagree with that one bit [laughs]. With Lemmy, what you see is what you get. As a person, he’s one of the nicest and most genuine people you’ll ever meet. It’s funny … he’s just so loyal to The Head Cat when he’s got so many other things going on around him. With who he is, he could easily throw his weight around in the studio or on stage—and it’d be typical—but it’s always a three-way decision on all things.

And with Nancy she would never call me Danny—she’d always call me Dan. She asked me when we first met if it’d be OK if she called me Dan because when she heard Danny she thought of boys. I told her I didn’t mind at all … but the only other person that calls me Dan is Lemmy.

To best describe the guitar tone from the first Head Cat album, I’d say it’s unruly, loud and completely rockin’. What is your typical setup for a Head Cat set?

A lot of our shows are one-offs or somewhere that we fly in, play a few shows and then leave so I generally request a 100 watt Marshall half stack. I’ve also used some Fender Hot Rod Devilles and turned them up as loud as they’ll go. This is the only gig that during soundcheck I turn my Marshall up almost to 10 and hit a couple chords and the sound man always gives me an OK sign and says, “Sounds great.” Any other gig I use much smaller amps and they always tell me I’m a little loud on stage and to turn it down a bit. With The Head Cat, no matter how loud it is, they always say, “Sounds great.”

We here at PG believe in the “relentless pursuit of tone,” what do you think makes up a good tone?

It is so hard to describe sonically what good tone is but I know it when I hear it. I really like when you hear a guitar tone that talks to you like a human voice as opposed to an electronic guitar. Over the years, I’ve come to the conclusion that a lot of that is in a player’s fingers and not the electronics. People like B.B. King can play any guitar and it’ll still sound like B.B. King, but plenty of people have Lucille replicas and don’t sound anything like him. Also, in a lot of the guitar tones I like there aren’t many effects between the guitar and the amp. I never got the idea of having vintage guitars and amps, but then have like 15 pedals between them [laughs]… that can’t possibly be that vintage tone those guys are looking for.

Danny B. Harvey’s Head Cat Gear

Guitars

James Trussart Rusty Steelcaster

Fender Jazzmaster reissue (owned by Lemmy)

Amps & Cabinets

Zinky Combo

Marshall Murder One duplicate (based on Lemmy’s original vintage JMP Superbass amp)

Fender Hot Rod Deville

Lemmy Kilmister Signature 1992LEM Super Bass Head

Marshall 4x12 (Celestion Vintage 30s)

Effects

None