Kim Thayil, the dropped-tuning lord of heavy grunge, walks us through the thickets of distortion, swirling psychedelic vortexes, and eastern-flavored motifs on Soundgarden''s epic return to form, King Animal.

Photo by Chris Kies

“I’ve been away for too long” wails Chris Cornell on the opening track of King Animal—the first album of all-new Soundgarden material since 1996’s Down on the Upside. Yes, you have—welcome back, guys. It’s been so long that even Axl Rose had probably grown impatient.

Soundgarden solidified its grunge-fueled ’90s legacy on bassist Ben Shepherd and drummer Matt Cameron’s locomotive rhythm section and Cornell’s iconic howl, which placed him alongside Kurt Cobain, Eddie Vedder, and Layne Staley on grunge’s Mt. Rushmore. But the linchpin that held everything together and gave it color and depth was guitarist Kim Thayil’s chameleonic playing, which is equal parts ominous, Tony Iommi-style riffing, psychedelically swirling rhythms, and droning, Indian-flavored soloing.

“We got together and jammed—we just let the music dictate to us before committing to or planning anything,” says Thayil of the long-awaited reunion. “If it still wasn’t there, I can honestly say this album wouldn’t have happened. It is still there and I’m just happy to be back playing music with friends that I enjoy the intimate sharing of ideas with.”

Rather than rehashing old material like Van Halen did this year with their much-anticipated comeback album, or trying to model the material after past successes the way so many other reformed groups have, the grunge godfathers branched out in the way longtime fans hoped they would—and in a way decidedly not foreshadowed by the uncharacteristically slick and mainstream-feeling “Live to Rise” theme they provided for The Avengers earlier this year. Examples of that experimentalism include Thayil’s mandolin solo and Pink Floyd-style wah trickery in “A Thousand Days Before.” Futher, both that track and “Black Saturday” also incorporate a Faith No More-style horn arrangement.

“I’m still an angry dude,” laughs Thayil, “I’m just older. I still push the band to be heavy and dark—that’s always been my role.”

New musical twists aside, Soundgarden is as complex as ever. King Animal represents the best elements of Soundgarden’s past, including the slow-motion, train-wreck grinder of “Rowing” (which is reminiscent of “4th of July”), the cruising-and-bruising rawness of “Been Away Too Long” (which carries echoes of “Spoonman”), and the alluringly creepy-crawly feel of “Bones of Birds” (think “Black Hole Sun”).

PG recently talked with Thayil about his unwavering love for Guild S-100s, how he sets up his chorus pedals, and why you should never call him a “lead guitarist.”

How was recording different this

time than in the ’80s and ’90s?

Well, we didn’t have predetermined

deadlines set by the

record company—that was great.

I originally thought we’d have

the bulk of this done by the

summer of 2011 [laughs], but

once we started rolling and felt

that inertia of the music coming

together, one of us would have

to head out for a tour, or Adam

[Kasper, producer] would end

up having someone else lined up

for the studio. I think the only

issue this time around was when

we’d reconvene and jump back

into an unfinished part or song

from the previous session.

You once said you brought

in your couch to be more

comfortable during the

Superunknown recording sessions.

Did you do anything

to help you concentrate and

execute in the studio for this

album?

[Laughs] No, no … I never

brought my own couch in—my

girlfriend would’ve killed me.

What happened was that, in the

main recording room, they set

up a standing lamp and a couch

from the lounge in the studio.

The room was so big, with high

ceilings and fluorescent lights,

and I just hated it because it felt

like being in a dentist’s office.

One thing I’ve always done

since that recording was dim

the lights, because I prefer the

evening feel that a darker room

presents. When the lights are

up, it’s like you’re doing work

in an office, but when it’s more

relaxed and a bit darker, I feel

more relaxed and creative in

that sort of intimate setting.

You’ve played Guild S-100s

since the early days. Did you

mainly use S-100s in the studio

this time around?

Yes, but I also used a Guild

S-300. A few years back, I

picked up a few late-’70s S-300s

that came with DiMarzio Super

Distortion and PAF humbuckers.

What I like about these

particular S-300s is that they

sound even louder and have a

more defined crunch to them.

Ben and Chris even commented

during the studio sessions that

they like them a lot because

they cut through really well and

have beef and body. Normally,

I’ll use an S-300 live when I’m

the only guitarist for songs like

“Outshined.”

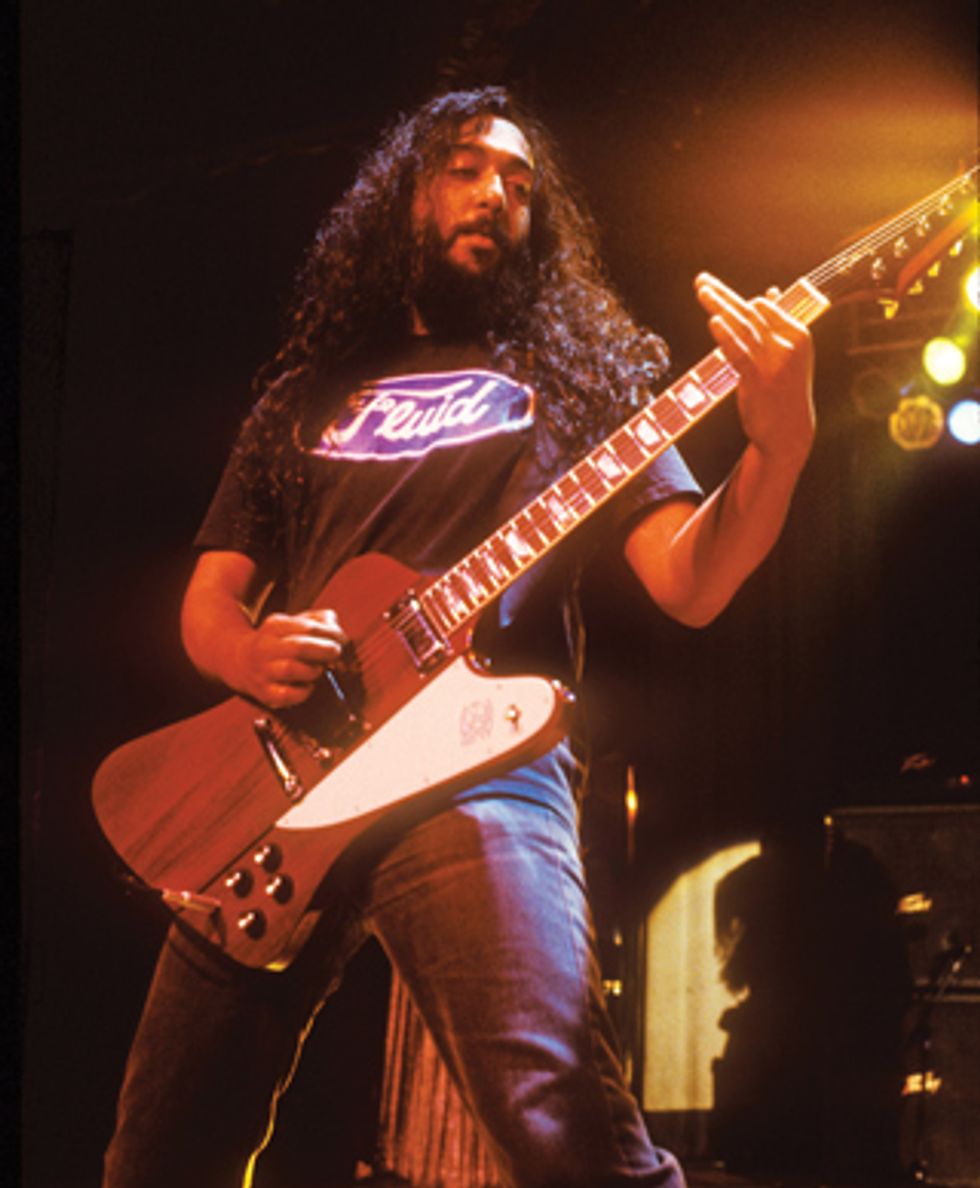

I used some Teles on the new album here and there, for when I play in the open C–G–C–G–G–E tuning featured in King Animal’s “A Thousand Days Before.” I played my Firebird quite a bit on King Animal, when I’m playing in the E–E–B–B–B–B tuning used on “Down on the Upside” and “My Wave.” For most of the dropped-D stuff, I use my S-100s. One of the surprises of the recording was our producer’s guitar, this Gibson Trini Lopez signature model, which was great for the clear, hollow, bell-like tones used for layering. I think the biggest thing for me—and the reason I need to get an ES-335 as soon as possible—is that the neck is so thin and fast with low action, and it has plenty of clarity and resonance.

Kim Thayil of Soundgarden plays a Gibson Firebird at the Hollywood Palladium in October of 1991. Photo by Marty Temme

What did you initially like

about the playability and tone

of S-100s, compared to the SGs

they’re obviously based on—

and are those the same reasons

you still mainly use them?

The neck is faster than the

standard SG necks. Secondly,

those S-100s were affordable

[laughs]… I was 18 or so

and bought it used in 1978

for about $200. But once I

really started to play that first

S-100, I realized how well it

played with low action. The

SG neck was thicker and

the fretboard seemed wider,

and my hands couldn’t really

navigate that as easily as the

S-100. I really like the stock

Guild pickups—I have all the

original Guild pickups in my

S-100s—because they produce

a hot, loud, rambunctious

tone, which I love! Plus, the

stock tuning pegs on the Guild

S-100s are Grovers and they

have the perfect ratio and really

take a lot of force to get out

of tune.

What amps did you use primarily

on the new album?

I mainly went with the stuff

I’ve been using live—Mesa/

Boogie Electra Dyne heads and

Tremoverb 2x12 combos. I

really paid less attention to the

gear this time around, because

I knew that the Mesa/Boogie

stuff was solid and has worked

for me. Other amps that I

plugged into during the sessions

were Matt’s ’60s Vox AC30,

Ben’s ’50s Fender Champ, and

Adam’s Ampeg VT-22, Savage

Audio Rohr 15 combo, Fender

Vibroverb, and Fender Pro Jr.

The Tremoverb was around in

the ’90s, but the Electra Dyne

is only a few years old. How

did you get hooked on that?

Our drum tech, Neil Hundt,

who was my guitar tech for

Lollapalooza 2010, happened

to have an Electra Dyne

head with a 4x12 when we

went to rehearse. When I got

there, Matt brought a Mesa/

Boogie Tremoverb combo

and Neil had one, too. I just

really liked how it sounded

and it felt almost instantly

like Soundgarden. What I

instantly noticed about the

Electra Dyne was how loud

and versatile it was. I’m really

able to have an organic, full,

pushed-gain tone that I can

back off with my volume knob

for the rhythm parts, like

during “Fell on Black Days”

or during the intro to “Black

Hole Sun.” I don’t really like

a quiet, thin, clean tone—it

might work when you have a

Tele and you’re playing country

or chicken-pickin’. I like it to

be thick, warm, and loud.

What is it you like about

how the Electra Dyne and

Tremoverb amps complement

each other?

Both amps have 6L6 power

tubes and are on all the time

and about equal in level—one

isn’t really dominant over the

other. The Electra Dyne provides

the top and the bottom of

the tone, while the Tremoverb

sort of fills the middle with

its focused, driven sound that

provides my tone’s bite. The

Tremoverb might get dialed

a little dirtier while leaving

more headroom on the Electra

Dyne set in the 45-watt mode.

The preamp level is about 2

o’clock and the master around

9 o’clock. I use both the red

and orange channels on the

Tremoverb set to vintage high

gain and blues.

“A Thousand Days Before”

has a “Burden in My Hands”-

type vibe, with tinges of

Indian sitar-like tones. How

did you get those?

I remember playing around with

a sitar during the Badmotorfinger

period, and I heard Metallica use

a sitar on Metallica in ’91, but

we opted not to use the electric

sitar because it sound a little

too gimmicky for us. The key

to that sound for what we do is

an open slide tuning, C–G–C–

G–G–E. That’s what facilitates

that droning effect. Before we

finished the song, its working

title was “Country Eastern,”

because we incorporated some

chicken-pickin’ playing, too. But

with that open tuning and the

S-100 and the amp’s tonal setup,

it gave it a very distinct Eastern

vibe. Underneath the main

guitar track there is an electric

tambura that Adam is playing,

which creates an odd groaning

sound. It works for that song

and how low-key it is, but I just

never want to overdo anything

like that … I want to avoid the

cheesiness. I also play slide guitar

on the Tele, and I doubled

the main guitar part with a

mandolin in the second and

third verse and at the beginning

of the guitar solo before it goes

into a doubled electric guitar

part that I play, technique-wise,

like slide and backwards—but

it’s not backwards [laughs]. I just

play as if I’m listening to a backward

guitar.

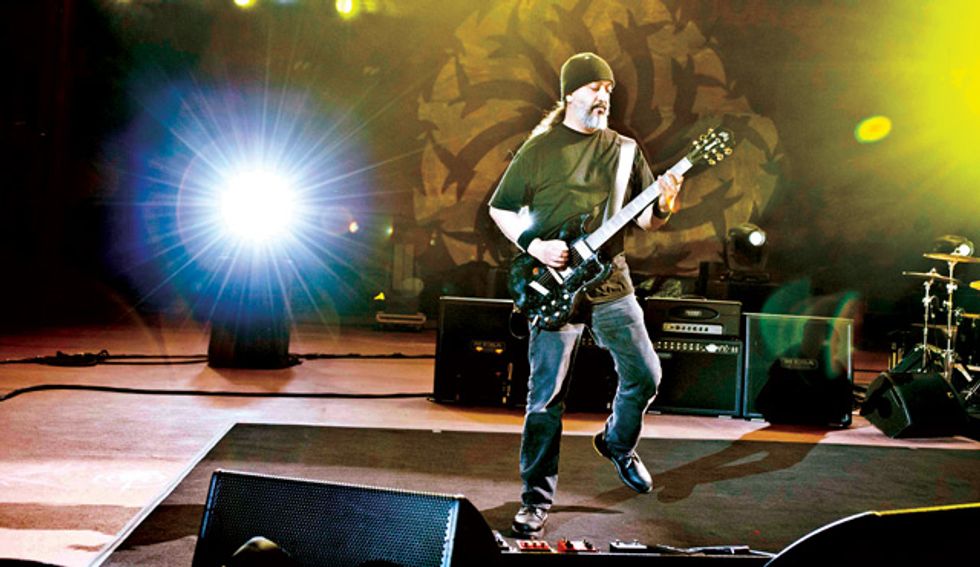

Thayil rocking out with his favorite Guild S-100 while being flanked by his Mesa/Boogie Electra Dyne and Tremoverb

amp setup during a performance at Red Rocks Amphitheatre in Morrison, Colorado, on July 18, 2011.

How did that idea come about?

The solo needed to go with the

Eastern vibe we play in the rest

of the song, so when I doubled

the guitar with that tuning it created

a bagpipe effect. I was blown

away because it’s a sound I love

from two of my favorite Velvet

Underground songs—“What

Goes On” and “Rock and Roll.”

I just kind of stumbled into it

with the tuning and mimicking

the background playing. We had

the mandolin soloing throughout

that whole section, but once we

got this cool, doubled-bagpipe

sound we decided to just have it

in the solo’s intro—it works like a

butterfly opening its wings going

from the single mandolin to the

two distorted guitars in that open

tuning playing off each other.

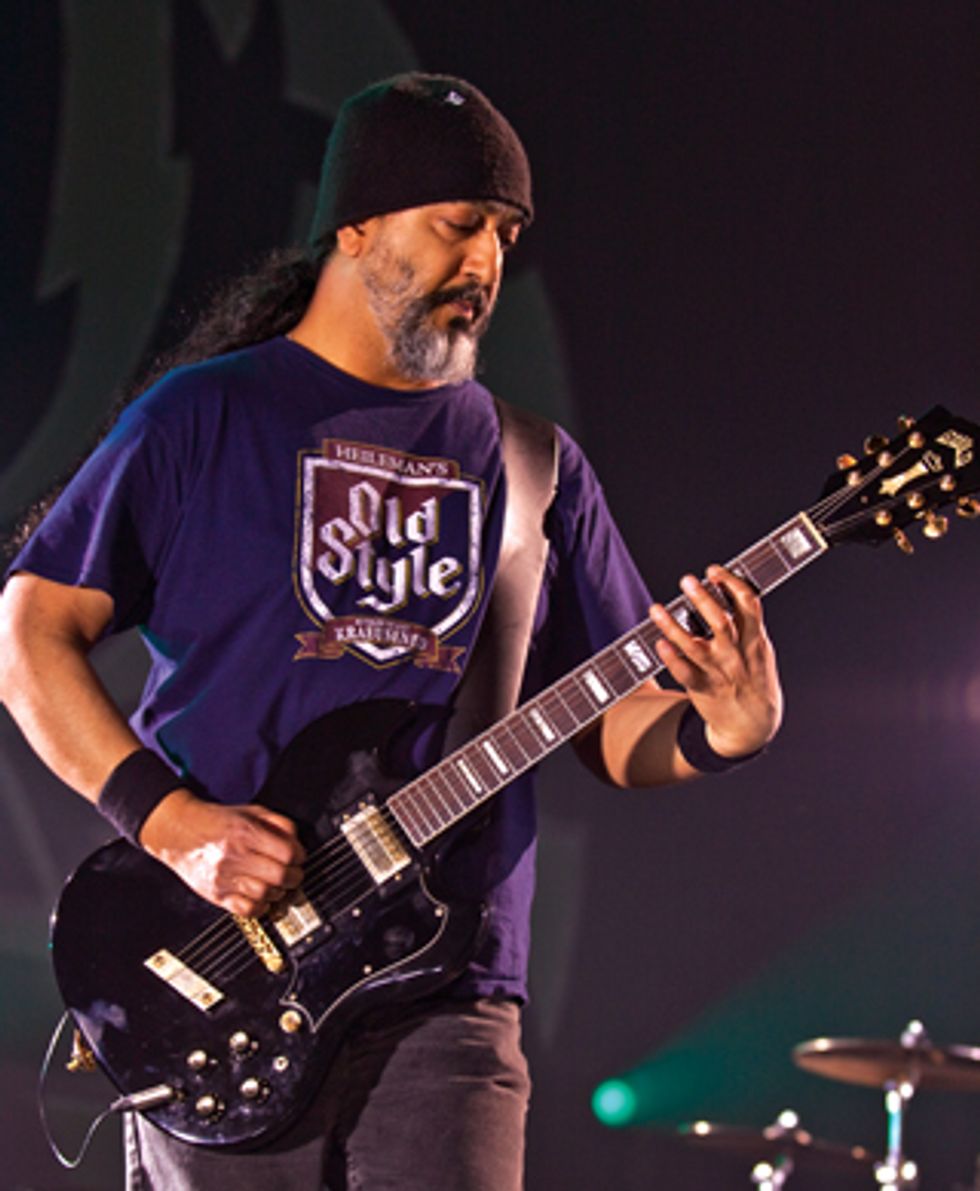

One of Kim Thayil’s favorite guitar pastimes is creating chaos. He gets inventive during “Spoonman” at the UIC Pavilion in Chicago in July 2011. Photo by Chris Kies

You’ve always had a knack for

ambient, psychedelic textures.

Back when we started in the

’80s—when it was me Chris

and Hiro [Yamamoto, original

Soundgarden bassist]—we

would call that sort of thing

“color guitar.” Those are the

parts that would augment a section—

we were particularly good

with that because we could hear

and picture things that were

either missing or could really

bolster a song. We’d be sitting

around listening or jamming

and one of us would be, like, “I

want to do this feedback thing

right here,” or “in this section

we could do this really heavy,

three-note arpeggio into the

verse.” I used to get so annoyed

when I’d see “Kim Thayil –

Lead Guitar” because I’d see

a damn lead guitarist in every

rock record and so much of

what we do is beyond chords

and notes—it’s about having a

feel for a different instrument

or different application of a

traditional guitar. I enjoy “color

guitar” as much as I do soloing.

In the last 30 seconds of “By

Crooked Steps,” the solo

guitar wanders into a tonal

frontier that sounds a little

like Tom Morello with his

DigiTech Whammy. How did

you get that trippy, atmospheric

effect?

I’m using the Trini Lopez. It has

a lot of room to play the strings

behind the bridge, and when

you do that while bending notes

on the fretboard you get this

really weird effect. If I pick a

note and rub the strings with

my thumb or the side of my

hand, I get this ringing, buzzing

sub-harmonic. What you hear at

the end of the song is me rubbing

the strings to get the ringing

effect, adding a long delay,

and then cranking the high

end on my amp to push it to a

real shrill squeal—like a dentist

drill—on top of me picking

some intermittent notes.

You’ve been using ethereal,

ghostly feedback parts as far

back as “Loud Love” [from

1989’s Louder Than Love],

and you use them this time

around on “By Crooked

Steps” and “Non-State Actor.”

What’s the trick to applying

feedback in a musical way?

You’ve got to have it loud enough

to feed back, but you can’t have

you can’t control it. I’ve found

that a bigger speaker, like a 15",

produces a nice, low-level hum.

We’ve always embraced feedback,

starting in the early days of the

band—I used to record with

Hiro’s backup Ampeg B-15 bass

amp. I would dial out most of

the low end and put in quite a

bit of high end with an Ibanez

Tube Screamer and a chorus

to get a brighter, more guitar-y

sound. When we jammed with

other people or they would show

us stuff, so many things were

undesirable, considered noise, and

deemed incorrect. But we keep

the incorrect things—they sound

heavy, chaotic, powerful, and wild.

I always have and always will push

the band in that direction.

Thayil plugs into Mesa/Boogie Electra Dyne heads, Tremoverb 2x12 combos, and Stiletto 4x12 cabs. Photo by

Josh Evans (Kim Thayil’s guitar tech)

“Blood on the Valley Floor”

and “Been Away Too Long”

have some of the album’s

chunkiest tones. Did you use an

overdrive or distortion pedal in

addition to the gain from your

amps, or did you get all your

dirt from the amps?

Heaviness with us never came

from just cranking the volume

and tuning the strings down.

We helped popularize the idea

of using alternative, lower tunings,

but we have this darkness,

this doom element in our songs

by way of the vocals, guitar,

and melody interplaying—it’s

those colored parts that kind of

change the chord and structure

just enough by combining major

chords with underlying, subdued

arpeggios, and ghostly ringing in

the background, coupled with

the dominant chords and vocal

patterns. We still enjoy the visceral

power of cranking things to

11, but the complex, cascading,

complementary dark layers you

can create are often heavier than

the visceral approach. Another

part of that is the odd time

signatures, like 7/4 or 5/4, that

are in some of our songs. I think

anything different or mysterious

can be channeled into heavy—

abnormality is a key.

That being said, the angry kid inside still loves getting loud. For “Blood on the Valley Floor” and “Been Away Too Long,” I might’ve used a T-Rex Dr. Swamp double distortion or the MXR CAE MC-402 boost/distortion during the solos. I mainly got my gain from overdriving the amps. My tech would be in the room changing the amps’ controls with gun-range ear protectors while I played and settled on the tones in the control room [laughs].

Many players think thick

tones require heavy strings

and picks, but you tend to use

lighter-gauge strings and picks.

In the early days, I used .008s

because I tended to play a lot of

hammer-ons, pull-offs, and really

long, exaggerated string bends.

But as I played more frequently,

I went up to .009s because the

.008s just got too loose and I was

playing more and more. Now that

we’ve been touring a lot again and

recording, I’ve gone up to .010s

after playing the .009s for a few

months, because my arm and

wrist got into shape. But when

you tune down to C–G–C–G–

G–E or E–E–B–B–B–E, the

lighter strings bend out of tune

more when you’re playing the

chord. Even if the tuners are keeping

them in tune when you hit the

open string, the chords are always

a bit more flimsy, so the heavier

strings give me more resistance.

And for songs like “Rusty Cage,”

I’ll have a guitar set with .010s but

with a heavier low-E string.

Photo by Josh Evans (Kim Thayil’s guitar tech)

What is it that draws you to

altered tunings?

It’s those sympathetic notes—

like in dropped-D you get

this beautiful droning effect

that’s in “Nothing to Say,”

where we bounce off the main

riff and the high D melody is

ringing open to get this spiraling,

psychedelic chaos. I play

similar droning parts this time

with “Worse Dreams” and “A

Thousand Days Before.” We’ve

always tried to capture a heaviness

and aggressiveness in ways

other than your standard guitar-volume

max-out.

Did you use the Hughes &

Kettner Rotosphere that so

famously defined your sound

on “Black Hole Sun” at all on

this album?

I still have that same Rotosphere

on my pedalboard, and I alternate

between the fast setting for

the verses and the slow setting for

the choruses. Other songs I use

it on are “Hunted Down” and

“Let Me Drown.” I use the high

rotor speed to emulate the Leslie

147 used on the record. For King

Animal, we would occasionally

use the trim pots to speed up the

modulation to more of a stun-gun

effect and put that through

an Electro-Harmonix Micro

POG—like in the guitar melodies

of “Been Away Too Long.”

Other applications on King

Animal are the glassy shimmer in

“Bones of Birds” and the swirl of

“Halfway There.”

I think I’ll be retiring the Rotosphere from the road soon, though. [Ed. note: Thayil’s tech, Josh Evans, explains that the Rotosphere will still be in use but will soon be located offstage in a rack, with Thayil accessing its two different speed settings onstage with a Radial BigShot SW2 Slingshot.] I also used my old Ibanez CS9 Stereo Chorus because it has this weird dark character I’ve only heard in that specific stompbox— it was the same pedal I recorded “Nothing to Say” and “Beyond the Wheel.”

A lot of players hate chorusing

because they think it sounds

cheesy or overproduced, but

the way you use it avoids that.

What do you like so much

about the effect?

For me and my playing style,

it’s perfect for harmonics, feedback,

and arpeggiated guitar

riffs, which have been big part

of my playing since Screaming

Life. That’s why I love and

abuse choruses so much. The

chorus plays well with all those

elements and gives a shimmer

and ring to my tone during the

single-note playing of arpeggios.

Plus, it gives a fuller, lusher

whoosh sound, too. And when

we play live and you have the

big speakers and you get the

feedback humming and you

add the chorus, it sounds like a

UFO landing [laughs].

“Bones of the Birds” also has

very complex, psychedelic

tones—especially when you

listen to it with headphones.

Can you describe the signal

chain you used to create that

soundscape?

During that song’s chorus—it’s

my favorite part—I’m hitting

harmonics in this ascending

melody. I’m playing that

through a stereo chorus, emphasizing

the harmonics alongside

the actual picked notes.

Kim Thayil's Gear

Guitars

’90s Guild S-100s, late-’70s Guild S-300s with DiMarzio

Super Distortion and PAF pickups, Gibson Firebird,

American Standard Telecaster

Amps

Two Mesa/Boogie Electra Dyne heads (set to 45 watts), two

Mesa/Boogie Tremoverb 2x12 combos, two Mesa/Boogie

Stiletto 4x12 cabs

Effects

Electro-Harmonix Micro POG, Dunlop/Custom Audio

Electronics MC-402 Boost/Overdrive, MXR M-151

Doubleshot Distortion, Dunlop/CAE MC-404 Wah,

Dunlop Rotovibe, T-Rex Reptile, T-Rex Dr. Swamp, Ibanez

CS9 Chorus, Hughes & Kettner Rotosphere

Strings, Picks, and Accessories

GHS Boomer .009-.046 and .011-.050 sets, Jim Dunlop .73 mm Nylon

picks, Boss TU-3 Tuner, Boss NS-2 Noise Suppressor, Lehle

P-Split High-Impedance Splitter, two Radial Engineering

BigShot SW2 Slingshot two-button universal remote switchers

(one for channel switching and varying gain in the Tremoverb,

and one for both engaging and alternating between slow and

fast Rotosphere settings)

What about the end, where it

sounds like birds?

That was a complete accident

that happened when I was fooling

around with my wah and delay

while playing with the volume

knob on my guitar. You bring up

the volume just enough to get

the squeal, and then you dial it

back and the delay really bounces

it around—like a bird cawing off

in the distance. Adam read that

Pink Floyd had done something

like that to get a similar bird-call

effect. It involved them using

a wah backwards—reverse the

input/output of your wah—

which makes it squeal quite a

bit, but you control that with a

volume pedal, and then you have

to time the delay just right and

it chirps off into the distance.

We recorded it a few times so it

sounds like a flock of birds, but

there are a few times where you

can tell it’s a guitar making the

noise [laughs]… I don’t mind

because, well, it is a guitar.

It seems that, while you love

gear that facilitates some of

your colorful tendencies, overall

you seem pretty disinterested

in seeking out the latest,

greatest gear.

Totally. When you’re younger,

you have to go to the store

and spend the money that you

worked all summer so you could

buy a new guitar or amp. You

knew exactly what you wanted

and needed—you studied viable

gear choices to pass the weeks

while saving up. Eventually, after

years of this and playing countless

pieces of gear—some perfect

for you, some you never want

to hear again [laughs]—you find

what works best for your band

or recording project. Knowing

what you don’t like or need is

half the battle with gear, but

you only find that out by playing

the stuff. We focus more on

the performance, song crafting,

and the creative elements within

the band. Sure, I like to tinker

around with sounds, noises,

and textures, but if it doesn’t

help build a better song, then

what’s the point? I’m not on a

first-name basis with my gear—I

know it’s surname, like Mesa/

Boogie or Peavey—but it never

has me over for dinner or anything

like that [laughs].

YouTube It

Dust off your flannel, prep your

stage-diving skills, and dial the

DeLorean for the early ’90s to

witness this hypnotically raw

performance of Soundgarden’s

“Jesus Christ Pose.”

Soundgarden’s official welcome

back party at Lollapalooza 2010

proved two things: Cornell’s

voice is still as fierce as ever,

and Thayil’s tone backs down to

no one.

The tar-dripping, swampy grinder

that is “Slaves and Bulldozers” is

quintessential Thayil—menacing,

down-tuned chords, deep string

bends, and a delay-minced wah

solo not to be missed.