Maine-based mathcore brainiacs Last Chance to Reason meld face-melting chops with mind-bending music theory and their own epic "Metroid"-style video game to mutate every notion you have about youth, metal, and gaming culture.

When you think about the preponderance of formulaic radio-friendly hits and the instant-gratification culture we’re fostering these days, things like skill and discipline can seem in short supply among up-and-coming performers. Some players may wonder why they should labor for hours, day in and day out, to become facile on their instrument and craft compelling songs when any 10-year-old with ADD can cut and paste GarageBand loops and become a YouTube sensation faster than your band can get tight on that tricky verse riff.

Technically oriented players love to pine for the good ol’ days when the art required major woodshedding. And the current reliance on Auto-Tune and other computer-generated audio tricks only fires that nostalgia.

Yet while the current musical landscape may seem bleak, all is not lost. Technology has made it easy to become lazy, but some of today’s bands are also churning out music that is taking complexity to levels never before reached. Take, Maine-based mathcore mavens Last Chance to Reason, whose recent release Level 2 is so dense and abstruse that it could give the guys in Dream Theater nightmares. Working from the band’s fully notated score, the concept album fuses Arnold Schoenberg’s 12-tone compositional theory with Meshuggah-like mayhem and superhuman guitar pyrotechnics. From beginning to end, with its relentlessly changing odd-meter sections and ultra-precise sixteenth-note sextuplets, the album is a virtuosic tour de force.

Last Chance to Reason was formed in 2003 at the University of Maine by guitarist A.J. Harvey and drummer Evan Sammons— both jazz and contemporary music majors— and bassist Chris Corey, who was in high school at the time. The band recorded an EP in 2005, and in 2007 a full-length album called Lvl. 1 followed. After several lineup changes over the years, guitarist Tom Waterhouse, a fellow University of Maine alumni, entered the fray prior to Level 2. Vocalist Mike Lessard and keyboardist Brian Palmer round out the band’s current lineup.

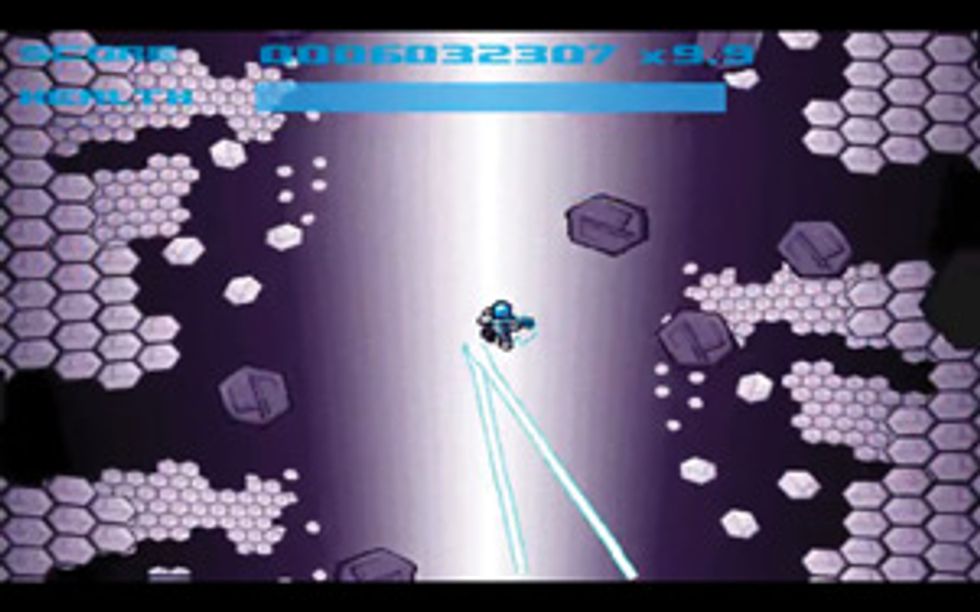

One of the more ironic things about LCTR is that they’re heavily influenced by an art form that might, at first, seem antithetical to their level of musicianship—video games. Their 2007 album Lvl. 1 was heavily influenced by the 1994 Nintendo game Super Metroid—which inspired the song titles “Escape from Brinstar,” “Kraid Ain’t Got Shit on Me,” and “Destroy Mother Brain.” Ever the overachievers, the band took the video game component of their own art a step further on this album—introducing a full-length video game that’s synchronized with Level 2’s underlying tracks.

We caught up with Harvey, Waterhouse, and Corey at their studio in the middle of one of their six-days-a-week marathon rehearsals as they prepare for their upcoming tour.

First off, what bands inspired you guys?

A.J. Harvey: Pretty standard stuff early on—Elvis, Aerosmith, Van Halen, and AC/ DC. When I started getting older, I got into heavier stuff.

Tom Waterhouse: Opeth, Dream Theater, Rush, Meshuggah, and Porcupine Tree.

Chris Corey: I really like a lot of old prog, like Yes, Genesis, and Rush.

And what about influences on your respective instruments?

Harvey: In the beginning, I liked Kirk Hammett and Dimebag [“Dimebag” Darrell Abbott, the late Pantera guitarist]. It evolved from there. I like Allan Holdsworth and Frank Gambale’s stuff with Chick Corea. I like John Coltrane, because he really shredded, for lack of a better word. I really like the caliber of lead playing or soloing that the jazz guys like Coltrane have—it’s ridiculous.

Waterhouse: Also Randy Rhoads. Those are probably our first influences.

Corey: On bass, my biggest influences would be John Myung [Dream Theater], Billy Sheehan, and Dan Briggs from Between the Buried and Me. Interestingly, probably the biggest influence—the guy who took bass to a new extreme when I was young—was Ryan Martinie from Mudvayne. He was the first guy I listened to where I heard the bass and was like, “Wow, that’s really, really awesome—I want to focus on this!” Before that, it was grunge and very simple stuff. Then I heard Dream Theater, and I just couldn’t believe it. I thought, “I want to play like that.” I played a 5-string at the time, and then I saw John Myung and he had a 6-string. So that’s what got me into playing the 6-string bass.

How did you guys come to develop an interest in jazz?

Harvey: When I was in high school, I saw John Scofield play with Karl Denson, which was great because it was a really good crossover [act]. It was jazz, but there were people dancing in the audience and there were computers and all sorts of sampling [going on]. It was a real jam-band audience. At that time, someone turned me on to [saxophonist] Joshua Redman, Mahavishnu Orchestra, and Tony Williams. I first heard the Brecker Brothers around then, too. Those guys are sick.

Waterhouse: Also, jazz guitarists like Kurt Rosenwinkel and Lenny Breau.

Corey: I’m not as jazz-inclined as these guys, but I do enjoy it and I can play some jazz. I wouldn’t necessarily walk into a jazz gig and get a lead sheet and say, “Okay, here we go.” I’d say I’m semi-comfortable playing jazz.

Last Chance to Reason (left to right): Chris Corey (bass), Tom Waterhouse (guitar), Evan Sammons (drums), Mike Lessard (vocals), Brian Palmer (keyboards), and A.J. Harvey (guitars). Photo by Jeremy Saffer

How did your jazz interests meld with your contemporary classical influences?

Harvey: I got introduced to the atonal thing in school, and Evan, our drummer, was into it, too. He, Chris, and I were writing in the practice room for Lvl. 1. All of the songs on that album are based on different 12-tone rows that we would just vary rhythmically throughout each tune. Once I started learning about 12-tone stuff, I started listening to dudes like Schoenberg—but not all the time. It’s not a huge part of my repertoire, I just throw it in here and there.

Can you explain the 12-tone row for those who are unfamiliar with it?

Waterhouse: The 12-tone row stuff is kind of simple in a sense, because it’s just making a melody out of twelve notes. In some cases, it could be just a riff in 6/8 or a riff in 6/4.

Is the same row used throughout the whole album?

Waterhouse: Yeah, it’s loosely based on it. It’s a theme that occurs throughout the entire thing.

Harvey: For “Upload Complete,” the first

riff is what I call a fragmented 12-tone

row, where it repeats the first four notes

twice, and then it adds three notes, and

then two more. The second riff is the

whole 12-tone row played in sequence,

in a simple rhythm [sings riff]. That

same 12-tone row also appears in “The

Prototype” and “Apotheosis,” but just

starts on a different note.

Harvey: For “Upload Complete,” the first

riff is what I call a fragmented 12-tone

row, where it repeats the first four notes

twice, and then it adds three notes, and

then two more. The second riff is the

whole 12-tone row played in sequence,

in a simple rhythm [sings riff]. That

same 12-tone row also appears in “The

Prototype” and “Apotheosis,” but just

starts on a different note.Does it continue in sequence after the displaced starting note?

Harvey: Yeah.

Waterhouse: But you’ve also got to stray away from it here and there, and rhythmic variation with Evan is a big part of that. It gives way to creating a full song just using a small idea, being able to create something larger out of a small number of notes.

Is an intellectual understanding of music needed to write and perform music this complex?

Waterhouse: Well, a big form of communication with us is notated music—that’s how we usually get things across.

Harvey: Chris didn’t go to school for music, but even so he can still definitely communicate with us. Sometimes I just shout out the notes to him and he memorizes it.

Chris, do you read notation?

Corey: Yes, I do read notation. I’m not

spectacular at sight-reading—it’s a constant

work in progress. I have a pretty good

understanding of the more in-depth parts

of theory. I’ve kind of acquired it all just

from playing with these guys—they’re all

very talented and very knowledgeable with

this stuff. I just try to play along and keep

up with the madness.

Corey: Yes, I do read notation. I’m not

spectacular at sight-reading—it’s a constant

work in progress. I have a pretty good

understanding of the more in-depth parts

of theory. I’ve kind of acquired it all just

from playing with these guys—they’re all

very talented and very knowledgeable with

this stuff. I just try to play along and keep

up with the madness.What was the writing process for Level 2?

Harvey: Level 2 wasn’t written in the practice room as much as Lvl. 1 was. We’d record fragments and ideas, and then Evan [Sammons, drummer] would put together the song skeletons. He would program drums, and then we’d go over it again and refine the parts a little more. Then we’d record them again. Some things seem complex, but they’re actually simple ideas.

Waterhouse: It was a collaborative effort. We all have a strong understanding of music theory, and everybody would experiment and bring something different to the table. After we all agreed on something, we would then move forward. A big part of it was the 12-tone row that we developed and used throughout the entire album in different ways.

Corey: We also have a video game that is programmed to run with the album. Certain things that happen in the game are accented by what’s happening in the song. For example, on beat one, the skulls will drop, and on certain parts with solos it will go into another section where things are bright and things are falling upward.

Did you employ compositional techniques like retrograde and inversion with your 12-tone rows?

Harvey: We did more with retrograde and inversions in Lvl. 1. There’s a song on the new record called “Portal,” which actually uses a different 12-tone row. It starts out by repeating the first five notes of the row, and then it busts into the song and I play three different inversions of the 12-tone row.

The repetitive structures in songs like “Coded to Fail,” “Temp Files,” “The Linear,” and “The Prototype” are reminiscent of phrases you might hear in the music of minimalist composer Steve Reich.

Harvey: Yeah. For example, “Coded to Fail” is based on three notes: C, B, and F. It’s just variations of rhythms on those three notes, based around the time signatures 7/8, 7/8, 5/8, 5/8, 3/8, 3/8, 3/8, 3/8. The three notes are rhythmically varied throughout the song and grouped into riffs. For example, the first riff is kind of a standard metal riff based on those three notes, but it does throw in a little run from F Lydian, too. Most of the material is based on the notes C down to B down to F—the interval sequence being down a half-step, then down a diminished fifth.

Conventionally, 12-tone rows are atonal. But does your jazz background cause you to think harmonically about what chords the notes in your tone row could fit over? For example, the C, B, and F notes could function as the b7, 13, and b3rd of Dm13.

Harvey: We’re not really thinking about the key when we’re writing the tone rows.

But it sounds like there are also discernible pockets of tonality in your songs.

Harvey: Yeah, and the vocal melodies will happen more in the parts where there are chord progressions. In “Upload Complete,” after we do the 12-tone row, it goes into something that’s more melodic, with an Eb5 pedal against Gsus accents. And there are four other chords throughout that part. The chorus goes Amaj7#11, C#min, Dmaj, and F#min, so it’s tonal but it’s not all in one key.

Are those chords derived from the tone row?

Harvey: Not really. We transition into it in some shape or form by combining some of the material from the tone row and some of the material from the next riff.

Are the songs conceived in 4/4 with superimposed meters, or is it all different time signatures?

Waterhouse: It’s all different time signatures. But one of the big efforts with this album was for it to be as close to 4/4 as possible. So it would be, like, 15/16, but if you play it four times through you get that feel.

Tom and A.J., you guys seem to be coming from different schools of shred articulation—A.J.’s doing more alternate picking, and Tom’s playing more legato.

Harvey: Yeah, John Petrucci was definitely an influence. I mostly use alternate picking in our material—all the sixteenth-notes and sixteenth-note triplets are played that way.

Waterhouse: I’m definitely more of the

legato guy, coming from my background

listening to Allan Holdsworth and Brett

Garsed [The Mike Varney Project, Derek

Sherinian]—who’s my favorite. I’ve been

really working on his hybrid picking

technique and trying to incorporate it

into the riffs. It’s more fluid and requires

less movement.

Waterhouse: I’m definitely more of the

legato guy, coming from my background

listening to Allan Holdsworth and Brett

Garsed [The Mike Varney Project, Derek

Sherinian]—who’s my favorite. I’ve been

really working on his hybrid picking

technique and trying to incorporate it

into the riffs. It’s more fluid and requires

less movement.How about when you guys play harmonized lines—do you articulate them the same way?

Harvey: A lot of the things we harmonize are more on the rhythmic side of things. On those, yeah, we’d be articulating the same way.

Did you record the stuff in chunks, or did you record whole passes?

Waterhouse: It was definitely chunks to keep that consistency. To be on par with a lot of other bands, we had to keep everything as tight as possible on the album.

Did you use click tracks?

Waterhouse: Yeah, we all do.

Do you have the click programmed into all of the different meters?

Harvey: It depends on the part. If the odd time signature is really characteristic of the part, the click will change with it. But if it’s an underlying thing that just creates more syncopation, the click will stay in 4/4.

Waterhouse: The click track is intense—all the accents, subdivisions, and time signatures are there. Evan actually plays the click tracks live.

Harvey: It’s on a sampler, and Evan’s got headphones on. One reason we do that is because there’s so much atmospheric stuff on the backing track—synth layers, different oscillators, distorted synth tones—that goes in sync with the music and comes in different parts throughout. The other reason is because it keeps the tempo consistent.

Are the song tempos also preprogrammed into your delay units?

Harvey: Yeah. For example, it’s 150 BPM for the solo in “Upload Complete.” Then the next bank is set at 180 BPM for the leads I have at that tempo in “Apotheosis,” and so on. I only use time delays on solos and leads, and I have consolidated all of my delay and harmony effects into two or three banks on my TC Electronic G-Major 2.

This would be a good time to talk about the rest of your gear.

Harvey: I have a new Ibanez S7320 7-string loaded with EMG 707s that I play through a Peavey 6505. I also push it with an Ibanez Tube Screamer. Venue to venue, the rig will have more or less gain for some reason or another, so the Tube Screamer’s drive is changed night to night, but it’s usually between 1 o’clock and 3 o’clock, while the level is between 12 o’clock and 3 o’clock.

Waterhouse: I have an old Ibanez RG7321 7-string that also has EMG 707s—but my neck pickup is tappable. I have a borrowed Carvin DC747 that is unbelievable, and an Eastman El Rey hollowbody too. I use a stock Mesa/Boogie Triple Rectifier with a Mesa oversized 4x12 cab, and I have the controls pretty much all in the middle. I also use a Tube Screamer to boost it a little bit and tighten up the low end of the oversized cab.

Corey: I play a Carvin BB76P Bunny Brunel signature 6-string. My B string has a Hipshot Xtender that tunes it down a whole step to A, and I use that on “Taking Control” and “The Linear.” My amp is an Ampeg SVT-3PRO head, and I run it through Avatar B410NEO and B212NEO cabs, which have speakers with neodymium magnets so it’s light on the lifting. I like them, but I’m looking to upgrade soon. I feel like anytime I’ve played out of an Ampeg 8x10, it just pushed a lot more power and had a lot more balls. But cabs are such a wide market that I haven’t really decided. Because of touring, I can only stop in a guitar shop so much.

Your music obviously demands incredible precision, but, live, there’s no margin of error. If somebody gets off by even a sixteenth-note, you could have a train wreck. Has that happened? And if so, how did you recover?

Waterhouse: It’s happened maybe once in the past year. If we fall off that badly, Evan can turn off the click track and continue. It takes a lot of listening to everybody else and making sure you’re right in the pocket. The jazz background helps in always knowing how to get out of it as quickly as possible.

I’ve seen the scores to some of your songs, and they’re as complex as The Rite of Spring. But, unlike orchestral players, you guys play everything from memory. How do you balance the showmanship aspect of a concert with trying to keep the music together?

Waterhouse: We do as much as we can onstage, but it’s really important to us to play the stuff correctly.

Harvey: At this point, we move to the rhythms and look like we’re feeling it, but not to such an extreme extent. We still try to keep some ounce of showmanship in there. We headbang, but we aren’t doing guitar whips—they’re not as conducive to sounding good.

Level 2: The Video Game

As if the tendon- and brain-synapse-busting chops of Last Chance to Reason's new album aren't enough work, the band also took on the herculean chore of working with software developers to create a PC video game of the same name that syncs with the new album. "Certain things that happen in the game are accented by what's happening in the song," bassist Chris Corey explains of the dystopian, futuristic-looking game. "For example, on beat one the skulls on the ceiling in one level will drop. And on certain parts with solos, it will go into another section where things are bright and things are falling upward." Corey says the game is "forward-scrolling," which means that "if you die, you just come back to life and the game goes on. You'll always be in the same spot in the song no matter how many times you die. It would be too complicated to work it out any other way."

Gearboxes

Photos by Jess Harvey

Tom Waterhouse's Gearbox

Tom Waterhouse's GearboxGuitars

Ibanez RG7321 7-string with an EMG 707 bridge pickup and a tappable 707 TW in the neck position, Eastman El Rey, Carvin DC747

Amps

Mesa/Boogie Triple Rectifier, Boogie oversized 4x12 cabinet

Effects

Ibanez Tube Screamer, Empress Effects ParaEq, Keeley Compressor, Boss DD-3 Digital Delay, Boss RV-5 Digital Reverb

Strings, Picks, and Accessories

D’Addario EXL110-7 sets (.010–.059), Jim Dunlop Stubby 2 mm or 3 mm picks, Monster Cable, Levy’s Leathers straps

A.J. Harvey's Gearbox

A.J. Harvey's GearboxGuitars

Ibanez S7320 7-string with EMG 707s

Amps

Peavey 6505 with Mesa/Boogie tubes, Peavey 5150 4x12 cabinet

Effects

Ibanez Tube Screamer, TC Electronic G-Major 2, Voodoo Lab Ground Control Pro, Voodoo Lab GCX Audio Switcher

Strings, Picks, and Accessories

D’Addario EXL110–7 sets (.010–.059) or EXL110 sets with an extra .059 or .060 for the low B, Jim Dunlop 1 mm picks, ISP Technologies Decimator ProRack G Noise Reduction System, Furman M-8 Power Conditioner, Korg DTR-2000 rack tuner, Monster Cable, Levy’s Leathers straps

Chris Corey's Gearbox

Chris Corey's GearboxBasses

Carvin BB76P Bunny Brunel signature 6-string with piezo saddle pickups

Amps

Ampeg SVT-3PRO head, Avatar B410NEO and B212NEO cabs

Effects

TC Electronic G-Major 2, BBE 362 Sound Sonic Maximizer

Strings, Picks, and Accessories

DR Hi-Beams MR6-30 sets (.030–.125), Furman RP-8 Power Conditioner, Korg DTR-1000 rack tuner, Monster Cable