Jaw-dropping classical guitarist Matt Palmer reveals how his love of ’80s shredders like Yngwie Malmsteen and an unwanted gift from his mother inspired him to turbocharge the “Classical Gas” mentality of yore and create his own mind-bogglingly fast nylon-string picking technique.

Matt Palmer’s main guitar was built in 2005 by luthier Kolya Panhuyzen. “There is a

ton of volume, but it can also sound really soft and delicate.”

| Hear a track from Un tiempo fue Itálica famosa: |

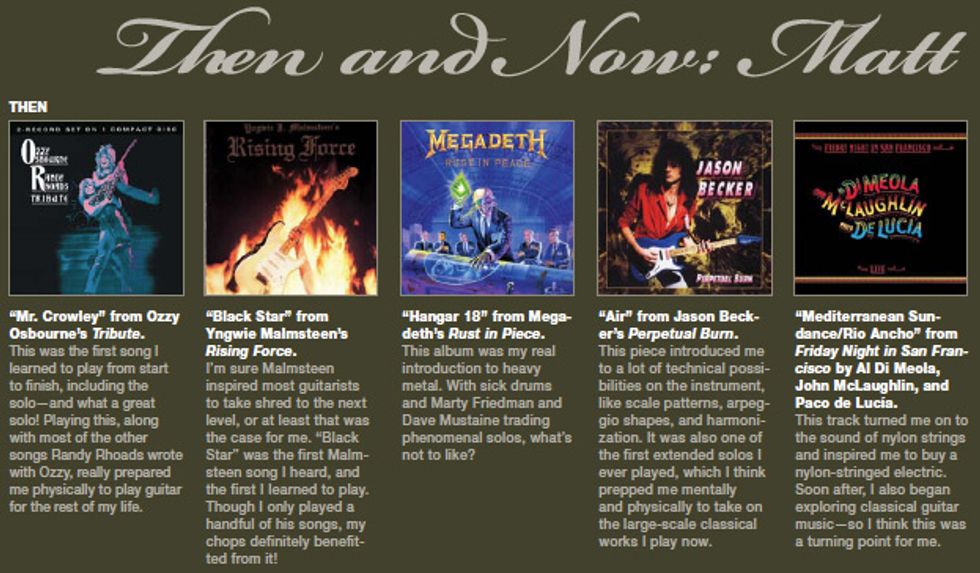

“I first got a guitar when I was about 10 years old,” Palmer recalls. “This was when Guns N’ Roses exploded on the scene, so I was really inspired by Slash. The image of a cool guy who played the guitar really spoke to me.” After poring over Slash’s whisky-soaked pentatonic licks, he moved on to the neoclassical shred deities of the period, foreshadowing a greater stylistic turn later in life.

“A short time after I started playing guitar, I got into Randy Rhoads—he was one of my big influences all through high school,” says Palmer. “I played everything off the [Ozzy Osbourne] Tribute album, and from there I progressed into really heavy stuff.” By that, he means the thrashing riffs of Slayer’s Kerry King and Jeff Hanneman, as well as Pantera’s Dimebag Darrell.

Although Palmer’s parents were supportive of his burgeoning 6-string interests, his mother gave him a gift she hoped would steer him in a different direction. “When I was about 16, my mom bought me a [classical-guitar veteran] Christopher Parkening CD,” Palmer remembers. “I threw it in my closet and forgot about it. I think she just got it for me so I would try something a little ‘nicer’—and that wasn’t as loud.”

Though Palmer dismissed the gift at the time, the whole incident foreshadowed a sea change that would happen just a few short years later. During his freshman year of college, he attended some classical guitar concerts—including by his future instructor Bill Yelverton— that blew him away in much the same way Slash had in his youth. And, just like that, Palmer switched musical paths decided to focus on classical guitar.

“When I first started I thought, ‘I’ll play the classical stuff because I like it, but I’m going to use all this musical training to make myself a better electric guitarist’—y’know, get the theory background so I could write great heavy metal guitar solos.”

When Palmer decided to record his debut album, Un tiempo fue Ital’ca famosa (which is named after the Joaquin Rodrigo composition it begins with), he took matters into his own hands and learned how to record himself. The result is a snapshot of a young artist about to make a real dent in the stuffy world of classical guitar. The pieces range from bursts of nylon-string virtuosity in the title track to the modern thunder of Czech composer Štêpán Rak’s “Sonata Mongoliana.” We caught up with Palmer to discuss his musical metamorphosis, how he gets distortion out of a nylon-string, and why he uses three types of strings on a single instrument.

Which shredders first influenced you to pick up the guitar?

After going through the Randy Rhoads stuff, Yngwie was really big for me. From there, I started to hear about other guys like Jason Becker, Marty Friedman, Chris Impellitteri, and Paul Gilbert. I was into anything and everything shredding and fast— like Slayer and Pantera. Today, I’m primarily a classical player, even though I think the term “classical guitarist” isn’t so great.

Why?

I think when most people hear “classical guitarist” there can be a negative connotation—like it’s not cool or it’s old and dated. When I was a teenager, I would have never considered listening to classical guitar. People might think it’s weird that I moved from metal and neoclassical shred to classical guitar, but I think it’s a natural progression.

How so?

If you look at it from a purely technical point of view, players from both genres are at the height of what they can do on their instrument. Both have spent countless hours in the practice room to get better. Musically speaking, both genres contain very dramatic and moving music.

A Christopher Parkening album turned you on to classical guitar. What caught your ear during that first listen?

It made me realize what the possibilities were with playing fingerstyle on classical guitar with all the different techniques like tremolo, crazy-fast arpeggios, and the contrapuntal stuff. During that time, I was a big technician, so I was always looking for the next challenge, and that was it.

Could you read music then?

At the time, I learned music by ear almost exclusively. So, I just started to learn these pieces off the CD by ear. I didn’t immediately give up electric guitar. I just wanted to explore this other aspect of guitar. There weren’t any aspirations of going to college at all—mostly because I didn’t know you could study guitar in college. Once I learned you could, I auditioned with these transcriptions I had done. I went to Middle Tennessee State University and studied with Dr. Bill Yelverton.

Did you take any formal lessons before college?

When I first started, my mom had me take lessons from a teacher at a local music shop. I took lessons for about a year and then decided it wasn’t for me. It wasn’t the teacher’s fault—I just felt I could do it myself. I really learned more about the technique side from playing Malmsteen and Marty Friedman solos.

I would imagine your first lesson in college was pretty tough.

It was humbling. I came to college with a lot of facility in my left [fretting] hand, but the right [plucking] hand is so detailed and integral to classical guitar playing that I pretty much had to start from square one. I was doing everything wrong. My nails were like an inch long. We just started with some real basic studies. It was a little discouraging, because I knew I was capable of doing so much more. I rolled with it and did the assigned studies, but on the side I was always working on something much more complex, hiding it from my teacher.

You developed your own picking technique—basically an expansion on classical tremolo technique [see “Step on the (Classical) Gas” sidebar at the end of the interview]—to play scales at fast tempos, right?

Right. Like I mentioned, my right hand was a mess, and I was coming up with my own ways of getting things done. The traditional approach of playing scales in classical and flamenco guitar is by alternating the index and middle finger. I think I was too impatient to allow it to develop, because it was frustrating that the right hand couldn’t keep up. I would throw in the pinky and use all the fingers on my plucking hand to play scales. Then I heard these guitarists just ripping scales and they were articulating every note, so I set out to figure out how they were doing it. When college was over, I had most of the system put together, and I’m really lucky that my teachers didn’t strike me down from developing that.

Now I can play tremolo as fast—well, almost as fast—as anyone can speed pick. You can keep going at it throughout an eight-minute piece, which just shows how efficient it is. Other guitarists have played scales this way. Narciso Yepes was probably the first. But when you look at the editions these guys have made and the pieces they’ve fingered, it’s a totally different approach than what I use.

How is your technique different?

It’s like an electric-/classical-hybrid left hand mixed with the a–m–i [ring finger–middle finger– index finger] plucking-hand stuff. Previously, it was more of a pure classical-position style of playing with the left hand, but I don’t think those two work together very well, because you get all these weird right [plucking] hand fingerings each time you move to a new string.

Your guitar sound on the album is huge. What guitar did you use?

I used a guitar that was made in 2005 by Kolya Panhuyzen, a German luthier who lives in Canada. It has a spruce top with Brazilian rosewood back and sides and a Spanish cedar neck. The elevated fingerboard really helps with getting to the higher frets on the guitar. I really like traditional solid-top guitars and the brightness of the spruce. For my fingers, a traditional build, as opposed to the newer double-top or lattice-braced guitars, has this definite breaking point. When you play hard, there’s a point where it starts to break up.

“I feel fortunate that we are living in a time when some really great guitarists/composers

aren’t trying to write like the great pianists from the 19th century,” says Palmer.

What do you mean by “break up”?

There’s a certain edge to it that kind of reminds you of distortion. If you play with that threshold, I think it’s really another means of expression. With the newer designs, my fingers can’t really get to that threshold. This guitar sounds beautiful in a concert hall—it sounds powerful and the vibrato is just incredible. There is a ton of volume, but it can also sound really soft and delicate.

What type of strings do you use?

I am weird with strings. I use three different brands at the same time. The lowest three strings are High Tension Hannabach 728s. They’re really powerful, handwound strings—like a Savarez bass string, but a little less scratchy. They aren’t so live that I get a lot of noise out of them. I use Normal Tension Savarez KF Alliance carbon strings for the 2nd and 3rd strings. The transition from the bass to the wound 3rd string is tricky—it doesn’t flow really well—so the carbon evens it out a little. On the 1st string, I use a traditional nylon High Tension Augustine Regal.

Nail length and shape are big topics among classical guitarists. How do you feel they affect your tone?

I have slightly longer nails than most classical guitarists. I don’t know if it comes from playing all the fast stuff, but I feel more secure with longer nails. Also, I play a little more across the strings than most players do. There is a slightly larger angle between my nails and the strings that produces a darker sound. My wrist position looks normal, but the way my nails grow a little bent produces that angle rather than coming straight across the string. So the longer nails get that bright sound back, instead of that mushy, dark sound you get from the parallel approach.

Whose tone really inspires you?

I have probably four guitarists right now that are most inspiring to me. If you are talking tone, I don’t think it gets better than David Russell. The guy has the fattest tone in the business, and he is so consistent and such an expressive player. Two other guys—Álvaro Pierri and Aniello Desiderio—are on a whole different level than anyone else right now. Sergio Assad is another of my biggest influences. He is probably the best living composer for the guitar—and the Assad Duo is just dynamite every time you see them.

You took a real DIY-approach to this album.

I’ve always been a DIY-type guy. From how to choose your equipment to positioning the mics, picking what room to record in, and the editing and mastering process, it was difficult—because I never had any formal training in recording. I wish I did, because I think with a very basic amount of information I could have recorded a lot faster.

What did you learn during the recording process?

|

What mics did you use?

I used a stereo pair of Neumann KM 184s about a foot away from the guitar. Having them that close brings up problems, though. You can hear the fret and nail noise, so sometimes I had to play more carefully—which I don’t like to do. I don’t consider myself a careful player. If there was a little noise but I thought the phrasing was good, I would leave it. I appreciate that when I listen to other recordings. If it’s not overly produced it can be a little raw, and I like that. When you play guitar, there are noises that will just naturally arise.

How do you see the art of classical guitar progressing?

I feel fortunate that we are living in a time when some really great guitarists/composers aren’t trying to write like the great pianists from the 19th century. They know how the guitar works and they are using that to create the harmony, rather than trying to make [another composer’s] harmony work on the guitar. People like Sergio Assad come to mind. He knows the guitar so well and has such a varied background with Brazilian, jazz, and classical music. We are really getting some great music for classical guitar.

Are you drawn to modern classical-guitar music more than traditional material?

I think modern music is superior in many ways. For example, you have Rak using all these technical innovations and coming up with cool textures that have never been heard before. Composers are using the guitar as a tool to get their voice out rather than trying to stick with a style of music that people will think of as “classical.” There are so many innovations with the actual construction of the guitar, as well. They’re making them a lot louder, and the increased volume makes it more suitable as a chamber instrument than ever before. It will be interesting to see what kind of instrumental combinations will develop just due to the technical and structural innovations of the guitar itself.

Do you plan on returning to the electric guitar?

I have always said I would go back to the electric guitar one day and bring my knowledge of the fretboard and harmony. I probably won’t do that.

Palmer’s Brian Dunn (left) and Kolya Panhuyzen guitars.

Matt Palmer's Gearbox

Guitars

650mm-scale 2005 Kolya Panhuyzen (spruce top, Brazilian rosewood back and sides, Spanish cedar neck) with elevated fretboard and Rodgers tuning machines, 650mm-scale 2010 Brian Dunn (spruce top, Indian rosewood back and sides) with elevated fretboard and Rodgers tuning machines

Strings

High Tension Hannabach 728 (6th, 5th, and 4th strings), Normal Tension Savarez KF Alliance Carbon (2nd and 3rd strings), High Tension Augustine Regal (1st string)

Microphones

Neumann KM 184 compact miniature cardioids (stereo set)

Step on the (Classical) Gas

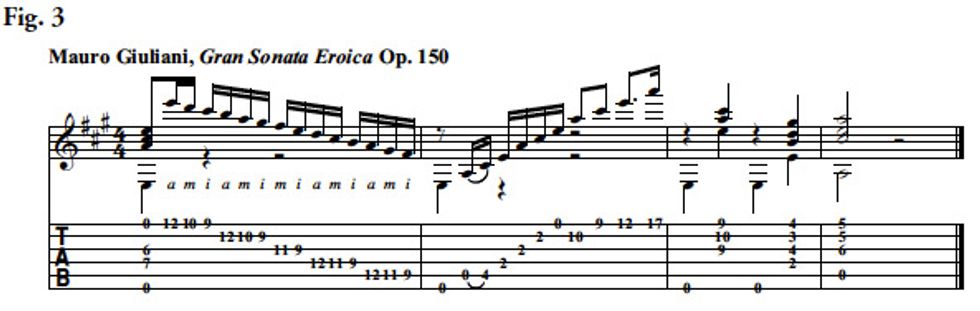

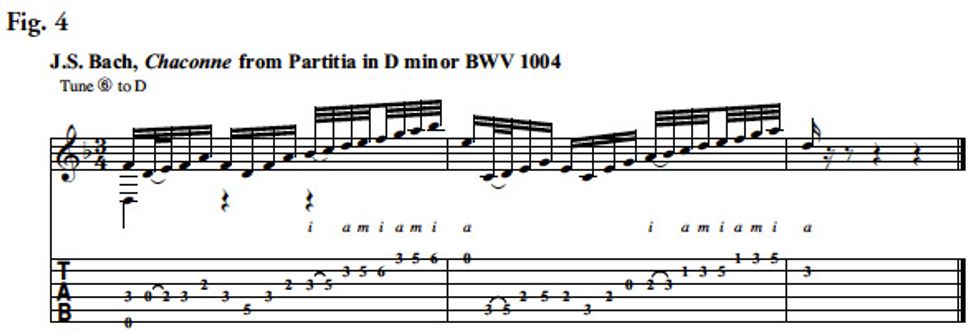

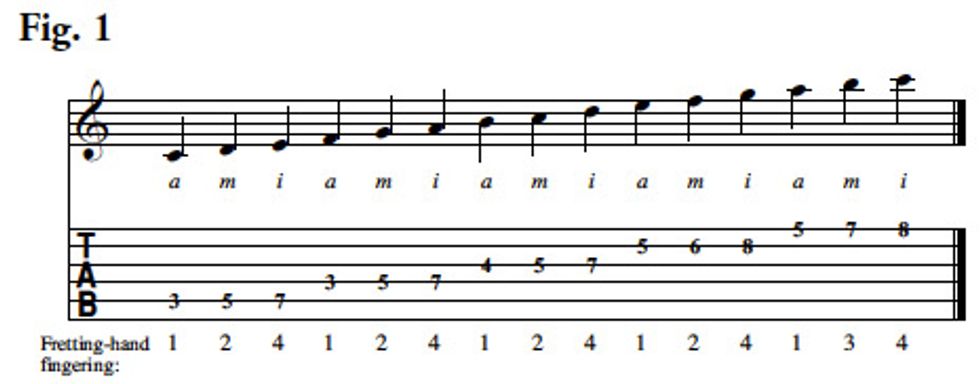

Matt Palmer breaks down his turbocharged hybrid plucking technique in this excerpt from his book The Virtuoso Guitarist, Vol. 1.

Classical plucking-hand fingering

p - “Pulgar” or thumb

i - “Indice” or index finger

m - “Medio” or middle finger

a - “Anular” or ring finger

The fundamental approach to this scale technique is quite simple. Pitches from a particular scale are arranged in three-note-per-string patterns, and the right hand repeats the fingering a–m–i. The sequence of attacks in the right hand is of the utmost importance. The sequence a–m–i follows the principles of sympathetic motion, much like the natural closing of the hand. It is therefore a naturally efficient way of moving the hand—similar to tremolo technique. The mastery of this technique can easily provide guitarists with a simple and effective method of playing scales on the guitar. Efficiency and ease of execution are key factors in the fluid and effortless technique required to play scales at great speed. Fig. 1 demonstrates the basic approach to a–m–i scale technique over an ascending C major scale.

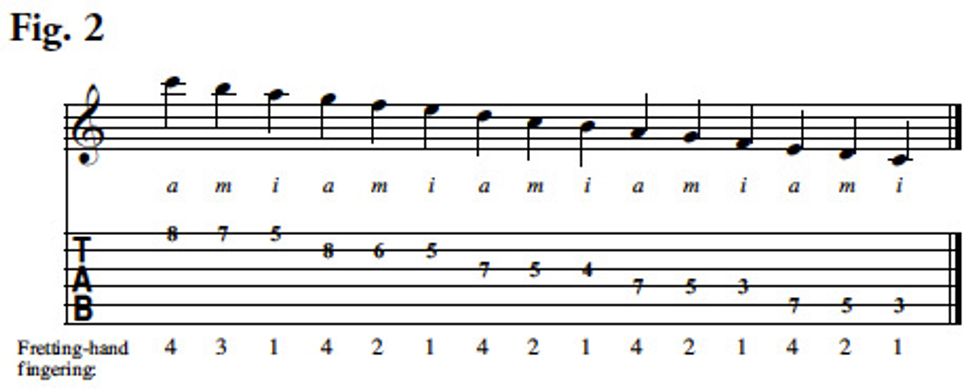

Observe in Fig. 2 how each string begins with an attack of the a finger. Furthermore, the attack of the a finger consistently coincides with the use of the left-hand first finger, while the attack of the i finger is with the fourth finger. In the descending scale, a similar consistency can be found. The attack of the a finger now coincides with the use of the left-hand fourth finger, while the i finger is with the first finger.

Important

As can be seen upon further study of this method, when playing scales that proceed stepwise I am always in pursuit of fingerings that allow me to maintain the consistencies found in figures 1 and 2. No matter the events that occur within the course of a scale—direction changes, shifts, strings with more or less than three notes on them, etc.—I always attempt to maintain or immediately return to the idea of three-note-per-string scales attacked with a–m–i. This adds a great deal of consistency to the method, and makes the process of fingering and executing these events much easier. Furthermore, as you will see in the advanced application of the technique, the vast amount of fingering possibilities that usually exists is replaced with a relatively small number of formulas that can be applied to various scenarios.