Primus’ Les Claypool and Ler LaLonde reveal how friendship and new tone toys helped them resurrect the most bizarre power trio of the last 25 years.

Primus (left to right): Larry “Ler” LaLonde, Jay Lane, and Les Claypool. Photo by Brad Hodge

| Listen to a track from Green Naugahyde: |

For Primus—hands down the most out-there new band when they emerged in the late 1980s and early ’90s—caricatures are everything. Bassist/vocalist Les Claypool’s playing is so wacky and mind-bogglingly over-the-top, his lyrics and vocal delivery are so off-the-wall, and guitarist Larry “Ler” LaLonde’s lines are so dissonant, that it’s a major miracle their 1990 album, Frizzle Fry, spawned a minor radio hit with “John the Fisherman.” Never mind that the following year Claypool’s even more avant-garde jibberjabber and the jaw-dropping bass tapping on “Jerry Was a Race Car Driver,” as well as the skwonky slapping and frenetic 6-string wailing on “Tommy the Cat” (both from Sailing the Seas of Cheese) were all over MTV and rock radio. Naturally, the videos were chock full of bizarre-o animation and claymation caricatures.

Looking back, the irony is that Primus’ story obliterates musicians’ favorite rhetorical caricatures of the 1980s and 1990s. You know—the ones that say rockers from the Reagan years all wore spandex, teased their hair, and played wanky solos on pointy-headstocked guitars over brain-dead eighth-note bass lines, while the ’90s supposedly had nothing to offer but plaid-wearing shoegazers who could barely play and who hated solos as much as themselves.

In fact, Claypool was as responsible as the Red Hot Chili Peppers’ Flea for sending legions of young bassists to woodshed on über-technical slapping and popping techniques. And LaLonde, who had studied advanced theory with Joe Satriani as a teen, was a uniquely qualified texturalist who could weave shredding atonal tapestries through Claypool’s outlandish escapades. And drummers Tim “Herb” Alexander and, later, Bryan “Brain” Mantia were technical powerhouses who completed the trio of strangeness. Primus was like Rush re-imagined by a mentally disturbed circus master.

But sometime in the late ’90s, the clever caricatures and celebratory weirdness started to lose their allure for the band. By 2001, Primus was burnt out—on the music and each other. Claypool thought they were done for good, but they decided to call their break a “hiatus.” While LaLonde worked on various projects—one with Brain Mantia, and another with System of a Down vocalist Serj Tankian—the Primus bass guru also stretched out. Among his endeavors was the fusion-y Oysterhead, which included legendary Police drummer Stewart Copeland and Phish’s Trey Anastasio on guitar, and Colonel Claypool’s Bucket of Bernie Brains had deep-fried freak show Buckethead on the 6-string, Bernie Worrell on organ, and Mantia on drums. Primus did regroup to tour a couple of times over the last decade, but Claypool says, “it just seemed like it was a nostalgic thing . . . we weren’t moving forward.”

But something happened in 2010. LaLonde and Claypool were hanging out as friends again, and on a whim, they got together and jammed with original Primus drummer Jay Lane—who cowrote the songs that got the band a record deal in the ’80s but left for good a month before they went into the studio. Seemingly just like that, the Primus magic was rekindled and plans for their recently released studio album, Green Naugahyde, were underway.

It’s been 11 years or so since Primus put out a studio album. First off, why? And second, what brought you guys back together?

Ler LaLonde: Well, after the tour for [1999’s] Antipop, we came home and never really got around to doing anything [laughs]. Usually, we come home from a tour and eventually we start something back up, but we never ended up starting back up.

Les Claypool: By the end of the ’90s, we were so burnt out on each other and the band and the whole bit that we were just making crappy music—if we were even making music. We were just in different [head] spaces: I had kids . . . they didn’t have kids . . . and we’d been doing it for such a long time that it was just time to stop. For me, on a creative level, it was just stagnant. I didn’t enjoy playing my instrument, I didn’t enjoy the music we were playing, I didn’t enjoy the scene that we had become a part of—we were doing the Ozzfest and Family Values tours and these other things that were just way more rock than I was really comfortable with. I don’t want to knock any of those scenes, but it just wasn’t where my head was at. We called it a “hiatus,” but it didn’t look very likely that we were ever going to do it again—but, y’know, never say “never.”

When I did Oysterhead, I had this epiphany: “Hey, there are people out there who want to see you play your instrument, and they don’t give a shit what kind of baseball cap you’re wearing or if it’s turned sideways or how baggy your pants are.” It was about showing your vulnerable side a little bit—going out there and dancing on the edge. It didn’t have to be perfect and so calculated. It made me excited about playing again. We played Pink Floyd’s Animals in its entirety, played King Crimson, Larry Graham, and Peter Gabriel—all these different things that were just fun to do. I spent a handful of years as a kid playing in all these biker bars with this R&B band, and this was kind of like going back to that again.

Les, what happened to change your mind about the “hiatus”?

Claypool: Well, I went off and did all kinds of stuff. These past 10 years formed the most creatively stimulating period of my life. I bought an old Airstream motor home and filled it up with my favorite players and started playing bars up and down the whole West Coast. We were staying in motels and sharing rooms. It was back to the trenches, and it was amazing. That was with [Colonel Les Claypool’s Fearless Flying] Frog Brigade.

Larry went off and did his thing, too, but we ended up getting back together in 2003 to do some touring, and we made that little EP [Animals Should Not Try to Act Like People]. That was fun. And then we did it again in ’06, but it just seemed like it was a nostalgic thing and we weren’t moving forward. A manager will always tell you—and I’ve been through a few of them lately—that “You’ve got to push the brand, build the brand, build the brand.” For me, that would’ve been a great business move, but on a creative level it was just not happening. So I finished up my last [solo] album and was wondering what to do next—Oysterhead, another solo record, another film project . . . there were lots of different options.

Larry and I had started hanging out again. He was in a different [head] space, and I was in a different space, and he really wanted to do Primus. So I said, “Let’s call Jay Lane.” Ler had never played with Jay, but I’ve played with him—besides in the early days of Primus—in the Frog Brigade, Sausage, and [Claypool’s 1996 solo project] Holy Mackerel. So when we sat down with Jay and started playing “Pudding Time” [from Frizzle Fry], the room just lit up. It was unbelievable. We just looked at each other and started laughing, because we knew this was amazing and it was time to do it again. So we decided to do some shows, and then a record . . . so here we are.

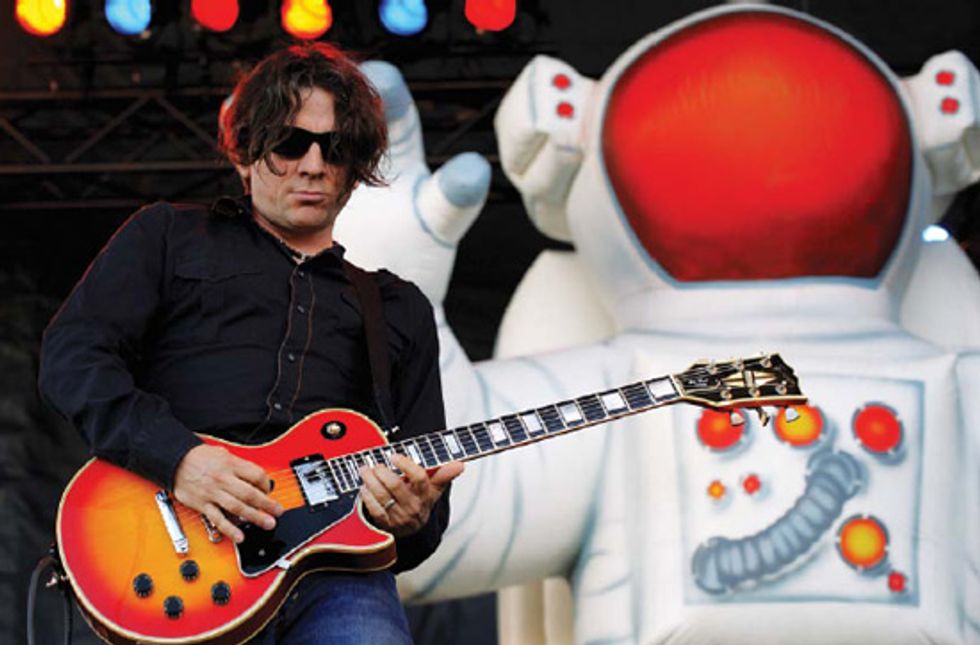

LaLonde in a rare moment playing a Les Paul Custom at a

2008 Ottawa Blues Festival gig. Photo by VANHORN.CO

What was so magical about that first time playing with Jay?

Claypool: First of all, Jay was the voice of the drum parts on those first couple of records. A lot of those original tunes—“Harold of the Rocks,” “John the Fisherman,” “Pudding Time,” even “Tommy the Cat”—were written when he was around, so they had that feel. Second, Jay is a very positive, happy, goofy guy. When he comes into a room, his energy is very . . . he’s like the Tommy Chong of drummers. He and I have a chemistry that I’ve never found with anybody except Stewart Copeland. We just click. Also, Jay has big ears—he hears every little thing, just like Stewart. So all of the sudden Ler was like, “Wow, I’ve got all this room!” I think that’s where that spark came from—it was a little different chemistry than we’ve had with Tim or Brain.

LaLonde: Jay will hear something you’re playing that you don’t even realize you’re playing—and then start playing off of it. So things start to evolve pretty quickly playing with him.

When Jay picks up on those little eccentricities, does it make you analyze your playing more and make it easier, or does it make it more difficult?

LaLonde: I think it does make you realize what you’re playing a little more, and maybe even make you feel like, “Well, if he noticed that, then I’ll throw in this extra part.” It inspires you to move on. It’s like, “Okay, that part’s already done—because he’s got it figured out.” Then I’ll start building on another part.

What are the highlights of the new album for you guys?

LaLonde: I was excited to get “Jilly’s on Smack” on there, because it’s a riff I’ve had around for a long time. So when I brought it in, everyone was excited and it came together really fast. “Internal Consumption Engine” is sort of a circus-y song that I’ve had around for a super long time. I think me and Les even did something with it right after the first or second album— or while we were on tour with U2 [in 1992]—but it never turned into anything.

Claypool: “Hennepin Crawler” is a really fun one to play. “Lee Van Cleef” is incredibly fun to play—I love playing that song. And Ler brought in a couple of tunes on this album, and “Jilly’s on Smack” is a really enjoyable song to play. It’s kind of a spooky, creepy, but somewhat lovely song. When Ler came in with it I was, like, “Oh my god, I’ve gotta play my upright on this, and I’m going to play arco [with a bow],” because I wanted to reinforce his part. For me to get in there and start thumping away would have cluttered things. If there’s something busy going on, I’m going to contrast it with some whole notes. If there’s a sparse element to it, I’m going to find the holes and fill them with some percussive stuff.

“Lee Van Cleef” is the most infectiously funky track on the album. What’s the story behind that song?

Claypool: A handful of years ago, this company sent me this resonator bass and said, “This is a custom bass. We want to make these for you. What do you think—will you endorse them?” I was like, “Oh, cool—custom bass.” And then I got it home and looked on the back and there’s this sticker that says “Made in China.” I was like, “What the hell is this!” [Laughs.] I let it sit around, and I plunked away on it once in a while. On my last record, I used it to get this Deliverance-y twang for a song called “Boonville Stomp”—and then I never put it down. It’s just a fun bass to get all swampy with. Prior to this record, if I stumbled across a part I liked, I’d just lay it down on a little tape recorder, and one of the riffs was that part for “Lee Van Cleef.” When it came time to make the record, I said, “Hey guys, check it out.”

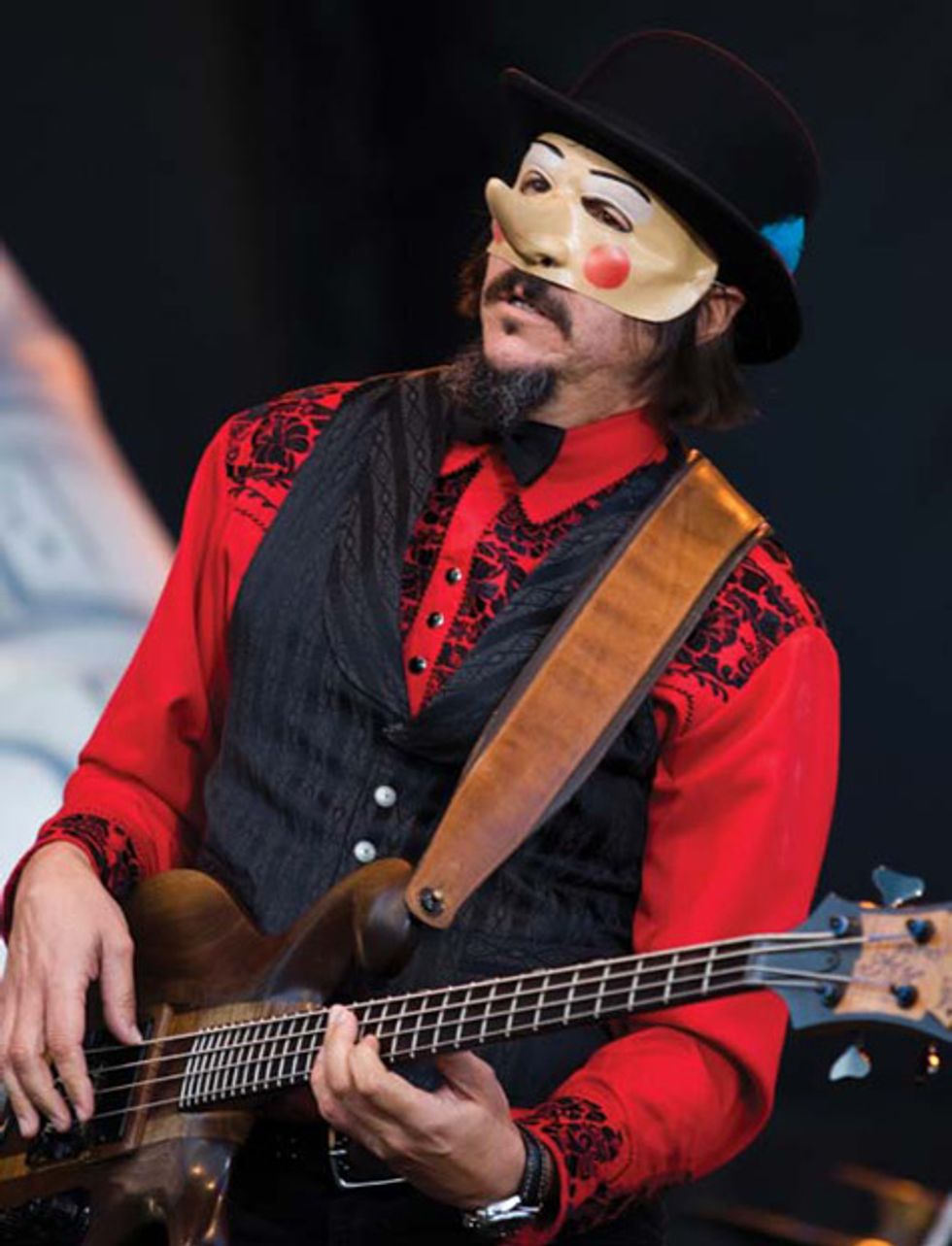

Claypool with his Dan Maloney-built Pachyderm signature bass prototype at a

February 2011 gig in Sydney, Australia. Photo by Cassandra Hannagan

What’s so fun about playing that bass, Les?

Claypool: I don’t want to knock anybody, but I took it to EMG to have a pickup put in it, and they were, like, “Oh my god, this thing’s really not very well made, it’s plywood. . . .” It’s a very inexpensive instrument. It’s a mess onstage. I’ll be playing “Lee Van Cleef,” and I’ll pull that D string and it’ll pop right out of the saddle, so I have to reach down and pop it back in . . . and the neck moves around. But something about it . . . it’s like a cool old pawnshop guitar with that janky sound.

Ler, “Tragedy’s A’Comin” has this rubbery, atonal guitar solo. What’s going on there?

LaLonde: There are a couple of solos like that where Les and I tried to notch it back a little bit—leave some space between the phrasing and do it in little bursts. Sometimes I have a tendency to just go crazy. The rubbery-type feel I think comes from playing up high and pulling off to open strings.

Ler, how did you get that super-saturated, endlessly sustaining metal tone on “HOINFODAMAN”?

LaLonde: I had a [Ted] Nugent or Neil Young-type, super-busting- up, amp-about-to-blow-up sound in my head, and I got that by cranking a Fulltone Ultimate Octave up all the way. I played a couple different tracks of that with a couple of different guitars . . . I don’t know how I’m going to recreate that sound live!

Let’s talk gear a little more. Les, you’ve been associated with Carl Thompson basses for a long time. Did you use those for this album?

Claypool: I’m playing this new bass that’s my own design—the Claypool Pachyderm—and it’s build by this buddy of mine from high school named Dan Maloney. He was a luthier for Zeta Systems, and he built my banjo bass and one of my uprights. We’re going to sell a handful of them. It’s something I’ve wanted to do for years. Carl is the super-genius, the Stradivarius of bass makers, but all his instruments are so unique—they’re like pieces of art—so it’s hard to get two that sound the same. So I decided I wanted to design exactly what I wanted—the most comfortable, user-friendly, easy-to-play bass I possibly could. And the prototype is what I’ve been playing for the last year or so.

Tell us about it.

Claypool: It’s very simple—one pickup, one Volume knob, one EMG pickup. The ones I use have the Kahler whammy bars on them. The shape is very ergonomic. It’s very light, and it looks cool. It looks like a cross between a Carl Thompson, a Rickenbacker, a P bass, and a Jazz bass—and it kind of is.

Ler, has your rig changed much?

LaLonde: It actually changed a lot for this album. I’ve always used Marshalls for everything, but I ended up using a Fender Super-Sonic head through an EVH cabinet. I was hanging out at the Fender factory, and they were like, “What are you using for amps?” I’d been trying a couple of different amp companies, and nothing was really working—it’s Primus, so it can’t sound too polished or hi-fidelity. We noticed as soon as I got the Super-Sonic that the guitar sounded a lot clearer than with the Marshalls.

Is it the 60-watt or the 100- watt model?

LaLonde: It’s the 60. I tried the 100-watt and I thought it was amazing, but when I played it with the band it was almost too much.

You switched cabinets, too?

LaLonde: Yeah. I was playing the Super-Sonic through my Marshall cabinet, and I really liked how it sounded, but they said, “Hey, would you be interested in checking out the Van Halen cabinet.” I was, like, “I guess so.” And then I tried it and I was like, “Oh my god!” It sounded like my old Marshall cabinet that I can’t seem to find, which had 25-watt Celestions. I thought it was going to be more of a new-school sound, but it reminded me a lot of a vintage Marshall.

What else has changed in your rig?

LaLonde: I totally redid my pedalboard. It’s been 12 years since we recorded, and back then if you wanted a vintage sound you had to actually find vintage stuff and try to keep it working. So it was great to find all these new pedals that have tap tempo for everything. I took time to try a lot of stuff, which I didn’t really have time or patience for in the past.

What did you end up with?

LaLonde: I got that Fulltone Ultimate Octave, which was a huge score for me, because I really didn’t use too many distortion boxes before. I got three MXR Carbon Copys, which are so cool because they’ve got that old-school analog thing, where you can grab the knobs and make spaceship sounds. Over the years of having digital delays, I kind of got away from that. I’ve got a Way Huge Swollen Pickle and Ring Worm, a Fulltone Mini DejaVibe 2, an EBS OctaBass pedal that I’ve had forever, and a bunch of Strymon stuff—the Brigadier delay, the Ola chorus/vibrato, the Orbit flanger, and the BlueSky Reverberator. Those pedals are all over the new album. I’ve also got a Dunlop wah that they custom made for me to recreate some earlier sounds I’d made.” [Dunlop’s Bryan Kehoe expounds: “Ler was having problems matching the sound on ‘Those Damned Blue- Collar Tweekers.’ He was using two wahs, one for ‘Tweekers’ and one for a regular wah sound. I told him we could put both sounds into one wah. We spent a couple of days dialing in the ‘Tweeker’ sound on a Dimebag signature wah and an EQ, then we customized a Custom Audio Electronics MC404 wah to match that ‘Tweekers’ sound and added a switch to click into the other channel of the wah for more subtle Cry Baby work.”]

How about guitars?

LaLonde: It’s all Fender now. The first couple of months of recording were either a ’69 Thinline Tele or a ’76 Strat— which is the sparkly green Strat that I’ve had forever.

That’s what you used in the early days, right?

LaLonde: Right. In the really early days, I also had a ’79 Strat that had a Floyd Rose on it. I routed it out with a steak knife or something to put in a humbucker.

You really used a steak knife?

LaLonde: Yeah. I didn’t know what a router was, and I didn’t know how to have it done, so I was, like, “Well, my mom has a steak knife. . . .” I don’t even think I soldered the wires—I just twisted them together. I didn’t even know where they went. I just moved the wires around until some sound came out the other end [of the cable].

Is the Thinline Tele a reissue?

LaLonde: No, I was actually going to sell it, because I have so much vintage stuff and I was getting tired of storing it and worrying about losing it. I took it to this guitar store in Venice and I was like, “Can you just sell this?” So they cleaned it up and rebuilt it, but when I saw it all put together I was like, “Maybe I’ll hold onto this one!” That’s probably the guitar I used the most on the album. It’s totally beat, but when we started going through guitars that was the one.

Is the ’76 Strat modified?

LaLonde: Just the pickups. I ended up switching them out for whatever comes in the American Deluxe Strat.

Did you use any other guitars on the album?

LaLonde: The other guitar was an American Deluxe Strat. The [S-1] pushbutton out-of-phase stuff and the hardware is just killer. That became my main guitar for playing live, and that’s how I ended up choosing those pickups for the ’76, too.

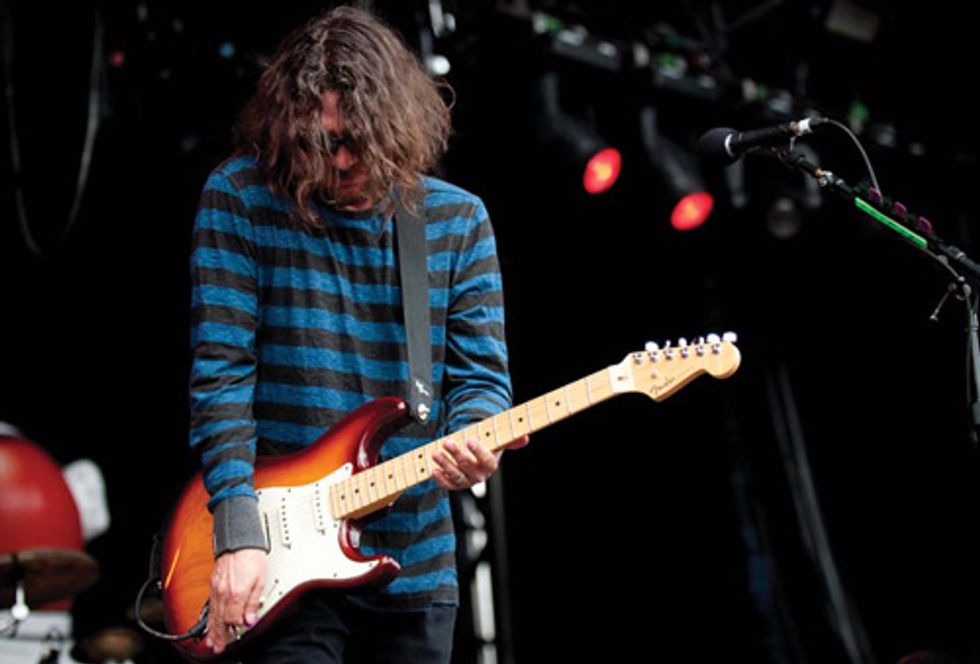

LaLonde onstage with his new Fender American Deluxe Strat at the 2011 Soundwave Festival in Sydney, Australia. Photo by Cassandra Hannagan

Okay, enough about gear. Let’s talk more about playing. Very few bands are defined as heavily by the bass as Primus is. What are the pros and cons of that dynamic?

LaLonde: Probably the con—actually, it’s a pro for me—is that the guitar isn’t as prominent. So I’m in the background a lot, which I enjoy because it gives me some freedom—but it doesn’t get you as much notoriety. But the only reason I want more notoriety is to try to get more gear [laughs]. But there are a million pros for me. A lot of bands I love—like Bow Wow Wow, the Police, and Iron Maiden—have a lot of bass. And in a lot of bands you can’t even hear the bass. Plus, it’s just fun trying to be more of a textural guitarist.

Les, what do you think was most instrumental in the development of your commanding playing style?

Claypool: I grew up listening to bands that were defined by the bass, because A) I’ve always loved the bass, and B) I was always drawn to ’70s soul music—which is all bass driven. I was also very drawn to Chris Squire and Geddy Lee. I mean, you listen to Yes records, and Squire’s bass is the loudest, most prominent thing on the record by far. Even Beatles records—the bass is huge. But [Paul] McCartney’s such a melodic and unobtrusive player that the girth and volume of it can be there without it being a distraction from the melodic element of the composition.

Ler, Can you take us back in time and tell us about the most memorable lesson you had with Joe Satriani?

LaLonde: At first, the biggest part was just sitting in a little eight-by-eight room and seeing someone playing like that. I’d never just sat by somebody who was that good. One lesson that clicked big was when he had that song “The Enigmatic” from [1986’s] Not of This Earth. At first when he was teaching me theory, it made no sense at all. I didn’t get how all the different modes worked together until he taught me a scale and had me play a part or a rhythm in that key, and he would solo over it in that key. Then he taught me the Enigmatic scale [Editor’s note: Italian composer Giuseppe Verdi invented the scale in the late 1800s.], and I learned the riff to that song and played it for him to solo over. And then he would play the riff and I would solo over it— which must have been pure comedy to see the contrast [laughs]. I didn’t realize you could make up your own scales and keys until he explained that to me.

Why was that so important for you as a player?

LaLonde: Because when Les comes up with a part, I’ve got to sit down and figure out what he played. He’ll play something and you can’t just go, “Oh, that’s in E major,” or something. I’ll have to pick out all the notes and make up new chords and scales within the key that’s been created.

Ler, when you were in high school, you were really into thrash and speed metal. What steered you off that path and toward a more avant-garde approach?

LaLonde: Everyone started trying to top each other with the speed and the growl and the heaviness, and it started to become this wash. It didn’t sound like music anymore. I was still in high school at the time, and I had a bunch of friends who were into the Grateful Dead. So I went and checked them out, and it was a completely different scene. Then I got into King Crimson. One day we went over to this older guy’s house to check out his new stereo, and he put on Frank Zappa’s You Are What You Is, and it just sounded insane. I was, like, “What is this music?” I went to the mall and bought the record—which had Steve Vai on guitar—and that changed everything.

Les, you and Flea have been copied a lot over the last 20 years or so. Do you ever feel frustrated that there doesn’t seem to be anyone new carrying that torch of bass originality into the future?

Claypool: To be honest, I don’t really pay attention to that. My favorite bass player of the past 15 years was Mark Sandman [the late Morphine bassist]. He was amazing—I loved his playing. It was so sultry and had such a huge signature to it, and yet he played a 2-string bass with both strings tuned to the same note— and he played it with a slide. But the emotion and the soul he had in everything he did was just, to me, phenomenal.

Today it’s so easy for young players to go on YouTube and learn anything that it seems harder than ever to be original.

Claypool: But there’s some kid out there right now who’s bubbling under the surface. The young players are starting where we left off, just like Stewart Copeland started where [John] Bonham, or whoever he was listening to, left off. There are guys starting where Stewart left off. Guys like Tim Alexander and [the Foo Fighters’] Taylor Hawkins love Stewart’s playing. I’m watching my son’s friends, and they’re starting with guys like me and Flea and Geddy. We went on this boat trip the other day, and my son’s friend was playing a bunch of Muse for me, and I was like, “Man, this is great stuff!” So, there’s always somebody there. It just depends somewhat on what the trends are. But there are some young kids out there that can totally eat my lunch, no problem [laughs].

It seems a lot harder to differentiate yourself though, because it’s so easy to hear and learn any kind of music. It seems like a path to the cliché, “jack of all trades, master of none.”

Claypool: Y’know, I haven’t really listened to bass players in many years. I don’t go buy records because of the bass player. But I did years ago. When I was a kid, it was every Chris Squire and Geddy Lee thing I could find. And then I stumbled across Stanley Clarke and—oh my god! You can look at me and look at Stanley and see where I got a lot of my stuff. I saw him play fairly recently, and he’s still just killin’ it.

Is Clarke the one who got you into slapping and popping?

Claypool: No. It was Louis Johnson on Don Kirshner’s Rock Concert. I was like, “Holy shit— look at that guy!” He used to stick his thumb out, like, a foot and a half away from the bass and smack away. I didn’t really have any money as a kid—I had like 10 records—but I had buddies whose entire [bedroom] walls and ceilings were covered with album covers, and I would go over and listen to music. I was sitting there one day when I was 14 or 15, going, “Oh man, Geddy Lee— there’s nobody better than Geddy Lee!” This guy who was older than me was, like, “I like Geddy, but, man, you need to listen to some Stanley Clarke and some Larry Graham.” He played me some Larry Graham and Sly and the Family Stone, and I was, like, “Whoa!” Then he played Stanley. I went by Musicland or one of those record stores, and there was I Wanna Play for You, when it first came out, and there he was on the cover, smoking a cigar with his Alembic bass. I bought it and opened it up, and there’s all the pictures of his basses . . . man, I ate that record up.

Claypool with one of his many Carl Thompson 4-strings at the Ottawa Blues Festival in July 2008. Photo by Jonathan Joncas

Did you learn those songs note for note?

Claypool: I didn’t have an amp, so I couldn’t hear myself when I was playing along with the records. Rhythmically, I could play a lot of the stuff, but who knew what the hell key I was in—all I could hear was the clickity-clickity-clickity. Maybe that helped me develop a unique style. But I think what’s going to keep me relevant is how I feel the music. If you just listen to me or Flea, you’re not going to have a very well-rounded way of expressing yourself on your instrument. But if you listen to a lot of different things—and not just the bass—you’re going to develop a unique style . . . if you have that in you.

Les Claypool’s Gearbox

Basses

Claypool Pachyderm 4-strings (maple body, walnut top, padauk pickguard, graphite-reinforced maple neck, ebony fretboard) with P-style EMG pickups and Kahler tremolo, seven Carl Thompson basses in fretted and fretless versions with various woods, Zeta upright bass, Bayou resonator bass

Amps

Two Mackie FRS2800 power amps, two Ampeg 4x10 cabs

Effects

Korg AX300B, Boomerang Phrase Sampler, MXR Bass D.I.+, MXR EQ, Line 6 DM4 Distortion Modeler, Line 6 DL4 Delay Modeler, two API 7600 channel strips (used for EQ and compression before Mackie power amps)

Ler LaLonde’s Gearbox

Guitars

1976 Fender Strat with Fender N3 Noiseless pickups, ’69 Fender Thinline Tele, 2010 Fender American Deluxe Stratocaster

Amps

Fender 60-watt Super-Sonic heads, EVH 5150 III 4x12 cabinets with 25-watt Celestion G12EVH speakers

Effects

Fulltone Ultimate Octave, three MXR Carbon Copys, Way Huge Swollen Pickle, Way Huge Ring Worm, Fulltone Mini DejaVibe 2, EBS OctaBass, Strymon Brigadier, Strymon Ola, Strymon Orbit, Strymon BlueSky Reverberator, two-voice custom Dunlop wah

Strings and Accessories

Jim Dunlop .009 sets, 1.5 mm Dunlop Tortex Sharp picks