Social Distortion frontman Mike Ness and co-guitarist Jonny Wickersham talk about P-90 addiction, Ness’ knack for engrossing lyrics, and what it was like for the Les Paul Deluxe-loving leader of the veteran punk band to sit in the producer’s chair for Hard Times and Nursery Rhymes.

|

“I think if I’d done this any sooner in my career it may have been a recipe for disaster,” says Ness, “but it was perfect timing for this album.” Jonny Wickersham, who’s played previously with Cadillac Tramps and US Bombs, also played a pivotal role in guiding Hard Times’s hot-rod groove. Wickersham— who had been co-founding Social D guitarist Dennis Danell’s long-time guitar tech—joined the band in late 2000 after Danell died of a brain aneurysm. The Ness-Wickersham teaming proved fruitful on their first collaboration, 2004’s Sex, Love and Rock ’n’ Roll, and their bond as musicians and friends has grown over the intervening years, as evidenced by their interlocking melodic guitar parts on tracks like “Machine Gun Blues” and “Far Side of Nowhere.” But it’s also palpable in arrangements like “California (Hustle and Flow)” and the drag-strip instrumental “Road Zombie,” where the two guitarists meld their love of Keith Richards’-style rock, ’70s-era NYC punk, old blues, and country.

We recently tracked down Ness and Wickersham during their fall tour to talk about vintage Gibson guitars, Ness’ first time in the producer’s chair, and how Neil Young’s guitar tech forever changed the Social D sound.

Mike, you’ve helped out as co-producer on Social D’s last four records—and your two solo records—but this time you took all the responsibility on yourself. From a guitarist’s point of view, what were the biggest challenges— and rewards—of doing that? And what did it teach you?

Ness: The album should be called Tones, because the biggest thing we focused on right from the start was getting guitar tones that matched our live sound. We did it old-school, with analog tape, an impressive Neve board, and all sorts of outboard gear, like Pultec EQs and Fairchild compressors. We also had technical help from engineer Duane Baron, who helped capture sounds and levels. Through this producing process, I’ve truly realized that, in a lot of cases—less is better. Instead of recording guitar after guitar, and stacking track upon track in the mix, I just recorded the setups we use live. I also learned that I liked producing a lot—it allowed me to have an incredible amount of focus on every single detail. We just wanted to make the best, most true-to-form rock ’n’ roll record we could possibly make without any compromises. When I look back in five or 10 years, I won’t have any regrets—that’s a real satisfying feeling.

Jonny, how has being in the band for several years now, as well as this new experience with Mike as the producer affected your playing?

Wickersham: When I was in the Cadillac Tramps, I tried to be this hot-shot blues player ripping through scales—playing too much, too fast, and being unfocused [laughs]. When I joined Social D, I thought I’d jump right in and handle it. Instead, I actually found out this thing called time. Mike has a sixth sense for time and groove—it’s in his blood. It all started with Mike taking me through the paces and showing me the songs and how they were to be played. And [former Social D drummer] Charlie Quintana gave me a metronome, too. That was the first time I played to a click track. It was elementary stuff, but it really tightened my playing and technique. The biggest thing I’ve learned working with Mike and Social D is finding and knowing the right feel, groove, key, and tempo for each song. For a band with a reputation like this, there has to be someone at the helm with a clear focus— and no one has a better vision or ear for what a Social D album should sound like than Mike.

Mike, if you could go back in time as producer of some of your earlier recordings, what would you change?

Ness: One thing that happened a lot during some of the older recordings is that there was this high level of compression. When I listen back now, some of the tracks just had the life and original tone squashed out of them. With this record, there was no one else to blame, so I did what I felt was right and sounded best.

Your singing sounds more natural now instead of pushing your voice to sound more aggressive. Was that a conscious decision?

Ness: Yes, definitely. In the past, I’ve had producers pushing me to be angry and aggressive and almost yell when I cut my vocals tracks. I always felt that was such a one-dimensional approach. On this record, I just wanted to go back and recapture my singing voice from the ’80s. If you’re aggro man from start to finish, there’s no room for dynamics or peaks and valleys of emotions.

“California (Hustle and Flow)” sounds like the Stones’ “Tumblin’ Dice” and “Can’t You Hear Me Knockin’.” How did that song come about?

Wickersham: Oh yeah, that Rolling Stones vibe was completely intentional—as a band we just thought, ‘lets go for it, man.’ We all have our favorite bands or groups, but if we all had to agree on our biggest influence, there’s no doubt it’d be the Stones. The best way to honor our heroes was to do something like “California (Hustle and Flow),” where we pulled out all the stops—with the rhythms, the riffs, the backup soul singers— and just go for it.

It started with Mike coming up with a riff that could’ve been on Exile, and once I heard him play through the chords a bit I just tuned to open G—just like Keith. Another thing Mike’s real good at—and which is evident on that track—is that he’s not afraid to play less for the betterment of the song.

Ness: Oh yeah, that was the whole point with this track—“How would a Social Distortion version of a Rolling Stones track sound?” My favorite part is the back end, where it goes from the main melody and rhythm and then just goes full throttle with a greasy, slutty rock groove that gallops to the end of the song. We had the song all the way done, but what I’d envisioned wasn’t matching what I was hearing on the track. I kept hearing these soulful background singers, so we had to at least try it. After hearing it once with the singers, I knew we’d done the right thing.

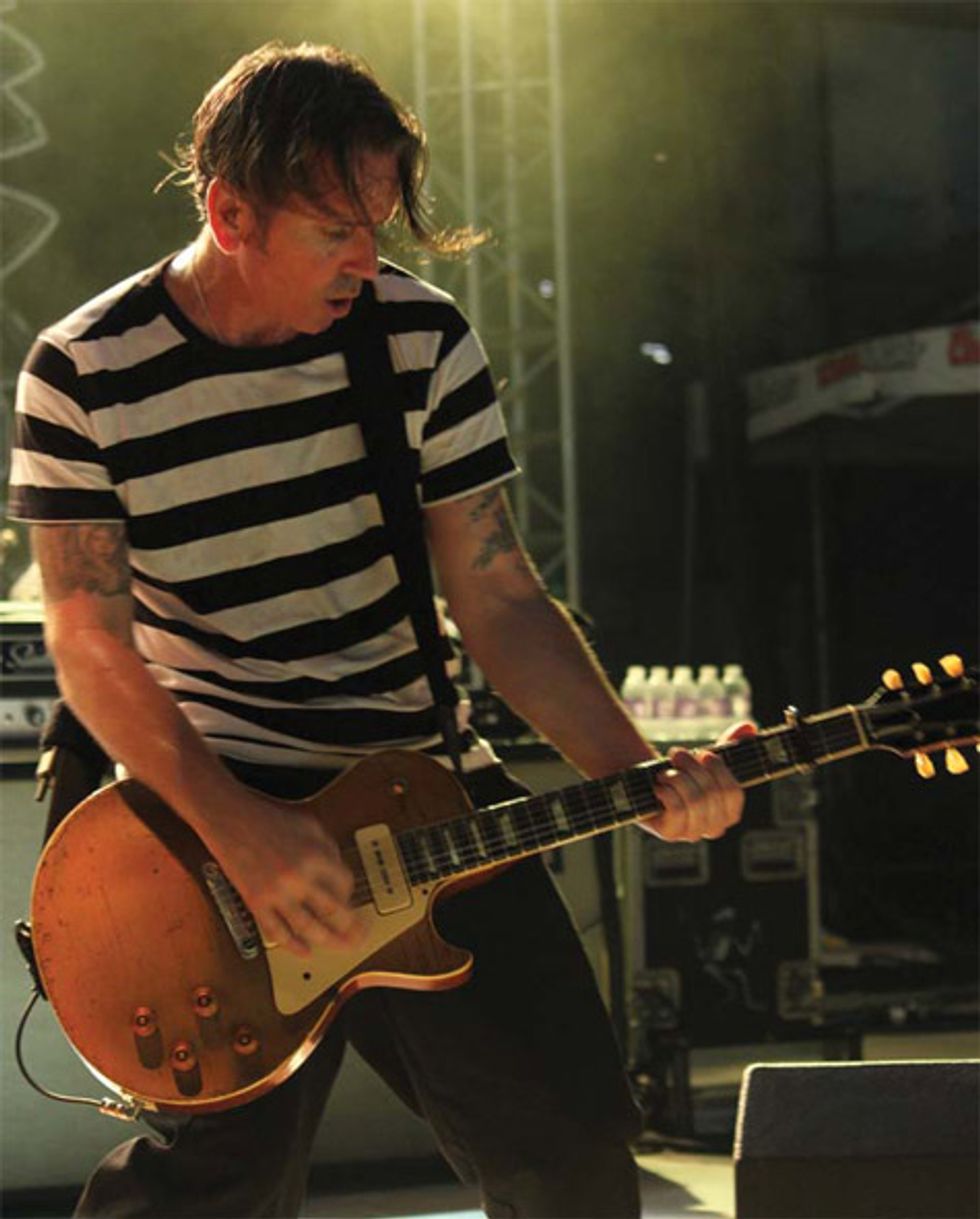

Jonny Wickersham with his 1954 goldtop Les Paul at Harrah’s in

Council Bluffs, Iowa, on August 10, 2010.

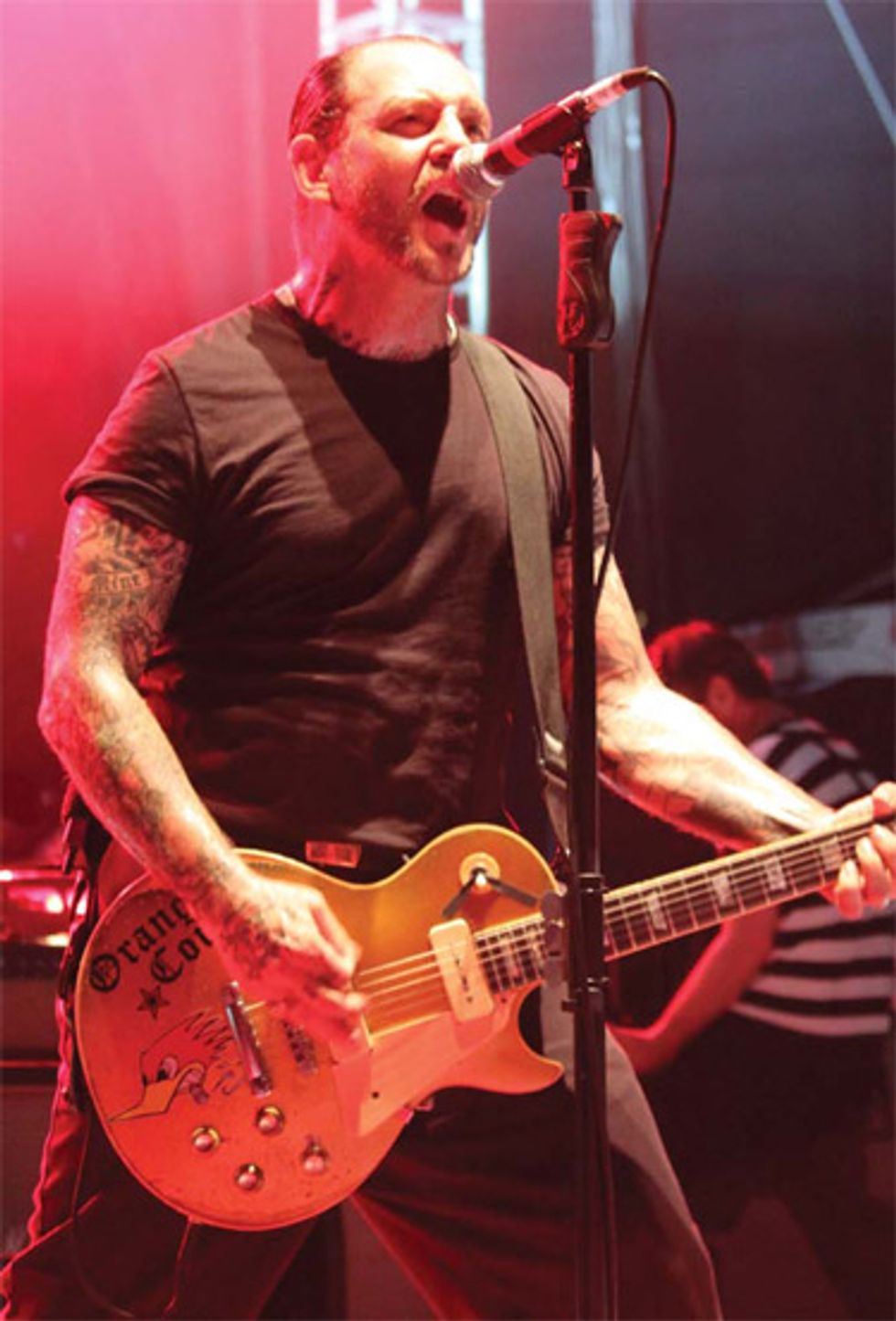

Jonny, it sounds like you’re playing a Tele for those slow, bluesy rhythms on “Bakersfield.”

Wickersham: We’ve been playing that song live for a long time and I’ve been trying to play it with a Les Paul Junior or an old goldtop, but it just never sounded 100 percent right. So when we sat down to record the track, I used all three on different takes, and the Tele just sounded the best—it cut through the mix with its very distinct sound and tone.

That Telecaster looks like it has a lot of stories.

Wickersham: That Telecaster is such a great rock guitar, because it’s an old blackguard with a rewound original bridge pickup done by Lindy Fralin. The pickup is just so chunky and thick—it even has a Les Paul bite to it when it’s pushed—but it still has that twangy Tele characteristic. It’s one of my favorite guitars in the quiver, but when I got it the pickup was dead, the neck-plate bolts were stripped, and the bridge wouldn’t stay on— that Tele was in pieces.

Jonny, you take the solo on “Alone and Forsaken” with your Les Paul Jr. How did you approach composing a solo for an old, slow ’50s country song like that?

Wickersham: I just went with the melody— just like Mike taught me [laughs]—within the song’s basic chord structure of Am-E-F#- C, and let that lead me, because you can hear where you should go when you’re following the song’s melody and rhythm. It’s not the flashiest thing I’ve ever done, but it serves the song and doesn’t get in the way or ruin the natural flow.

At the beginning of “Still Alive,” there’s a great interplaying riff that carries the song and is sprinkled later again in the chorus. How did you come up with that?

Wickersham: It started off this warmup-type riff I play—this droning thing I do with chords that just rings out each individual string I hit. It makes it sound like a lot more is happening than my two hands are actually doing [laughs].

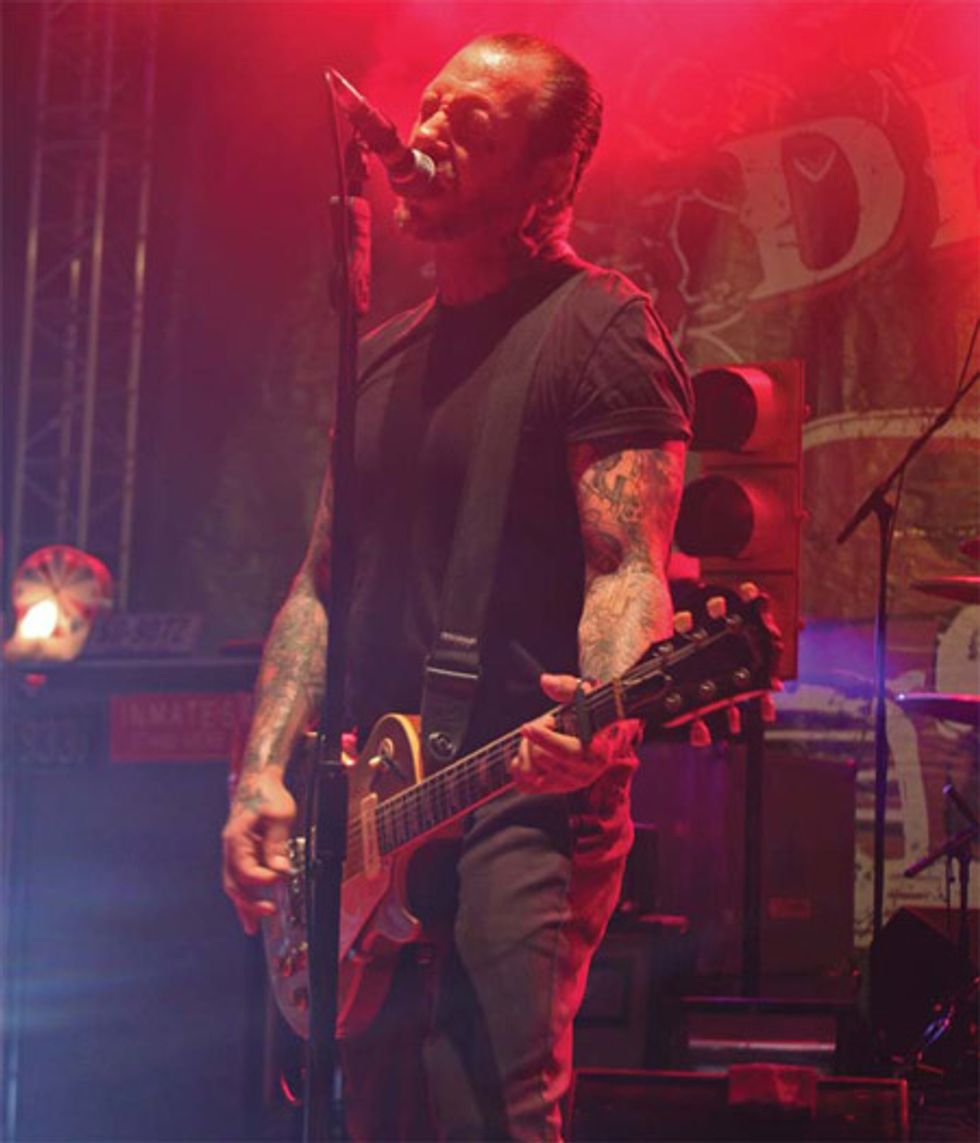

Let’s talk gear. Mike, during Social D’s Mommy’s Little Monster and Prison Bound eras, you were using SGs. In the ’90s, you made the switch to Les Paul Deluxes. Why the switch?

Ness: I always thought Les Pauls would be too heavy and restrict me when I was onstage, so I just stuck with what worked—my SGs. But once I tried the Les Pauls, I just fell in love with their sustain right off the bat. It’s incomparable. And the tone of those thick, mahogany Les Pauls is something I really took on as my new sound. In a way, it reshaped Social D’s sound.

Leaning in toward his ’67 Bassman and Marshall 4x10 cab, Ness conjures some juicy feedback.

Which guitars did you use most for the new album?

Ness: My absolute favorite guitar right now is a ’76 Deluxe goldtop with a mahogany body, a maple neck, and custom Seymour Duncan P-90s—and I usually capo it at the second fret. The other one I used a lot is my number-one early ’70s Deluxe sunburst, which has a mahogany body and neck. That has P-90s, too. Those Deluxes are like the perfect combination you’d see on an old hot-rod dragster—once you find a winning setup, you don’t want to deviate from it at all.

Wickersham: Man, I wish I could find more spots for my Tele, because I love that guitar and how it sounds. But for the majority of the tracks I used my ’57 Les Paul Juniors. One is a tobacco burst that is a bit darker sounding and the TV yellow one has a hotter pickup, like in the 8 kHz range—but it’s not so hot that it’s too bright. It’s a nice contrast with the darker, tobacco burst because it has a little bit more top-end and clarity. For the solo on “California (Hustle and Flow),” I used a friend’s ’54 Les Paul goldtop with original PAFs. It gives that track’s guitar parts a little more focus and precision with this cool, honky hollowness that adds another layer to the song.

You play your vintage guitars under the hot lights where they get sweat and beer all over them. Why not keep them at home in their cases and use reissues for the road?

Ness: Well, mine are still pretty affordable because they’re older, but they’re not Holy Grail vintage. That’s what I like about my ’70s Deluxes—whether it’s the all-mahogany ones or the ones with maple necks [Ed.: Gibson changed the neck construction from mahogany to maple in 1975]—I can get a great vintage tone without playing a $25,000 guitar onstage.

Wickersham: I’m only going to do this thing once, so why not play the shit—that’s why Leo and the guys at Gibson built them, right? [Laughs.]

Jonny, you also use VOS Gibsons. What do you think of those?

Wickersham: They’re great guitars that are well built and a solid option if you can’t get an original, but I put different pickups in them because the standard VOS pickups have a thin, pointy tone that’s not very versatile. I generally put Luther Lee P-90s in them, because they tend to be thicker, more responsive, and have a woodier, more natural tone.

Speaking of P-90s, Mike you’re a big fan of P-90s, too.

Ness: I’ve always loved the creamy, smooth tone that Neil Young had during the Ragged Glory tour, so I asked his tech Larry Cragg about Neil’s setup. The biggest thing he said that gave him that tone was the P-90s in his Les Pauls. I was used to playing humbuckers, but after putting a pair of custom Seymour Duncan P-90s into one of my ’70s Deluxes, the resulting tone was a bit brighter, a little warmer, and more transparent than the humbuckers. But what I really liked about them was their solid midrange, distorted creaminess, and their ability to still hold definition when put through an overdriven tube amp. I’ll put up with the hum any day to have my current tone.

What amps have you been using?

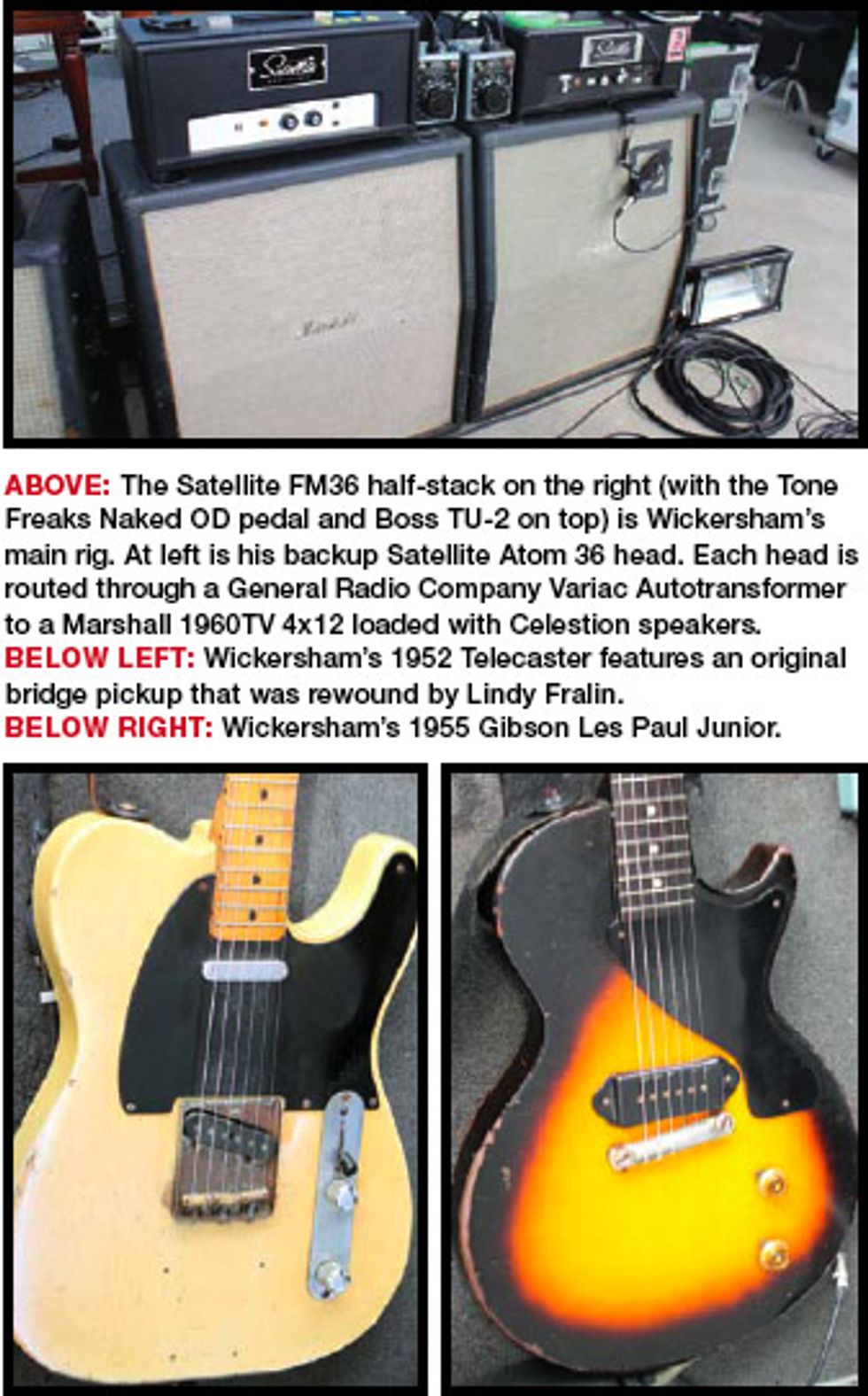

Ness: My first amp was a Bassman with a 2x12 extension cab. I didn’t even know how to play yet, but I knew the amp had to be up to 10 to sound good. It would carry all the way through the neighborhood, and the cops would come over and say, “If you’re going to play that loud, why don’t you learn to play ‘Smoke on the Water’ right?” [Laughs.] Once I got the combination of a Bassman head, Marshall 4x10 with 30-watt Celestions, and a Les Paul Deluxe with a P-90 in the bridge position [Ed.: Ness tapes all his pickup selectors down so he doesn’t accidentally switch out of bridge position], I knew I wouldn’t be changing anything. And that was over 15 years ago. That ’67 Bassman is like a small-block Chevy—it always starts and gets me where I’m going. For this record, I primarily used my ’67 Bassman, but there were a few overdubs and layered parts where I used Jonny’s Satellite FM36 [Ed.: The FM36 is now known as the Atom 36], which has a class-A, Supro- or Valco-kind of vibe that really complements the Bassman.

Wickersham: I used my ’60s Vox AC30 Top Boost and my Satellite FM36 head. Both were going through my two Marshall 1960TV 4x12s, and we blended the tones for my tracks.

Jonny, how did you get turned on to Satellite heads?

Wickersham: I was doing a show in San Diego and my buddy said I had to check out these amps that were built in town. So they both came down before the show and Adam [Grimm, of Satellite Amps] brought one of his first heads, and we plugged it into my Marshall TV 4x12s. I remember I was playing my ’59 Junior and all I could think was, “Man, this is happening.” At the time, I was using a ’69 plexi and a ’72 metal-faced Marshall—amps that make people look at me like I’m crazy to have them onstage—but the Satellite was just bringing it as well as those old Marshalls. And for what we do—onstage and recording— Adam’s 36-watt head is perfect. I mean, I was spoiled for years with those two Marshalls, but the Satellite heads I’ve been using are exceptional. Everyone tends to hang tightly to those sought-after guitars and amps—including yours truly—but the great thing about gear is trying new stuff and being happily surprised.

Mike, Fred Taccone of Divided by 13 Amplifiers works on your Bassmans. What type of stuff does he do to your heads?

Ness: [Laughs.] I don’t exactly know what he does to my amps, but I know that I look for a hotter, more overdriven tone at a lower volume. To get a great, rockin’ tone with most older amps, you need to push the amp and its power tubes. I was just looking for a way to heat ’em up at a lower volume so I wasn’t blown off the stage.

Jonny, what special needs do you have with amps?

Wickersham: I’m not a big fan of master volume amps. I know there are several different ways to configure the wiring and inputs for them, but in any application I’ve used them in, they sound thin, with no oomph, and have unpleasant, brash overtones because of the preamp having to do so much work. With those old Marshalls and the Satellites I’ve been using, I just crank ’em up and get the tubes cooking to get that big, natural power-tube sound. I also use a Variac to get my tone at a volume my ears and body can handle [laughs].

You guys don’t use a lot of pedals, but have you discovered anything new that you like lately?

Ness: The only stompbox I used in the studio and on tour currently is my tried-and-true Boss SD-1 distortion box. I really only use it during certain solos or parts where I just want to push it a bit hotter without losing too much definition.

Wickersham: I used to love my second-generation Ibanez TS-9 Tube Screamer, but I’ve grown weary of that tone. I was producing this band called the Strangers, and they had a really cool pedal called the Tone Freak Naked OD. It’s right in between a distortion box and ’60s fuzz, with this nice, open, sloppy overdrive that adds some hair but never gets too loose or undefined that it’s out of control.

Because he injured his fretting hand during his youth—and because it aids his

singing—Ness often uses a capo at the second fret.

Mike, you injured your left hand when you were a kid. How has that affected your playing?

Ness: It’s definitely very limiting, and I’ve had to adapt just like anyone else with an injury. I can’t bend my left index finger any further than 90 degrees at the first knuckle, so I have to make an A minor chord with my second, third, and fourth fingers. Since I don’t have the full use of all four digits, it changes what blues scales I can do efficiently—and the manner I can do them in. I’d be a lot better guitar player if I had all four fingers working normally [laughs].

I also tend to use the capo quite a bit, because it puts less stress on my hand when I go to make certain open chords—plus it allows me to sing in a different key, which is more of a comfort thing. I love using open chords, because they’re just full and thick and can ring out forever—especially with my Deluxes.

Speaking of long-view things, one of the most notable things throughout Social Distortion’s history is the personal, honest nature of your lyrics and stories. Where does that come from?

Ness: [Laughs.] Life, man, life—that’s the greatest inspiration source I’ve had. The funny thing about it is that you can’t control when it comes to you. It just hits you when it wants to, and you’re at inspiration’s mercy. I believe every person has a gift or ability. Some people are mechanically inclined, others are gifted with a brilliant mind, some are artistically creative, and I’m just lucky that I’ve been blessed to put lyrics together and tell a story through my music.

Mike Ness' Gearbox

Guitars

1939 Gibson J-35, four Gibson Les Paul Deluxes— a ’75 goldtop,a ’76 goldtop, a ’71 sunburst, and a ’75 sunburst—with custom Seymour Duncan P-90s

Amps and Cabinets

1967 Fender Bassman modded by Divided by 13’s Fred Taccone, Marshall 4x10 loaded with 30-watt Celestions

Effects

Boss SD-1 Super OverDrive

Strings and Picks

Ernie Ball 2215 Skinny Top/Heavy Bottom strings, .88 mm Dunlop Nylon picks

Jonny Wickersham's Gearbox

Guitars

1947 Gibson J-45, ’52 Fender Telecaster, ’54 Gibson goldtop Les Paul, three Les Paul Juniors (a ’55 sunburst, a ’57 TV yellow, and a ’59 cherry-red double-cut), two Gibson VOS Les Paul Juniors loaded with Luther Lee P-90s

Amps and Cabinets

Satellite Amps FM36 and Atom 36 heads, Marshall 1960TV 4x12s loaded with Celestions, mid-’60s Vox AC30 Top Boost

Effects

Tone Freak Effects Naked OD, Boss TU-2 tuner

Strings and Picks

Ernie Ball 2215 Skinny Top/Heavy Bottom strings, .92 mm Dunlop Tortex picks

Miscellaneous

General Radio Company Variac Autotransformer