He argued that tape machines don’t work better, musicians work better with tape.

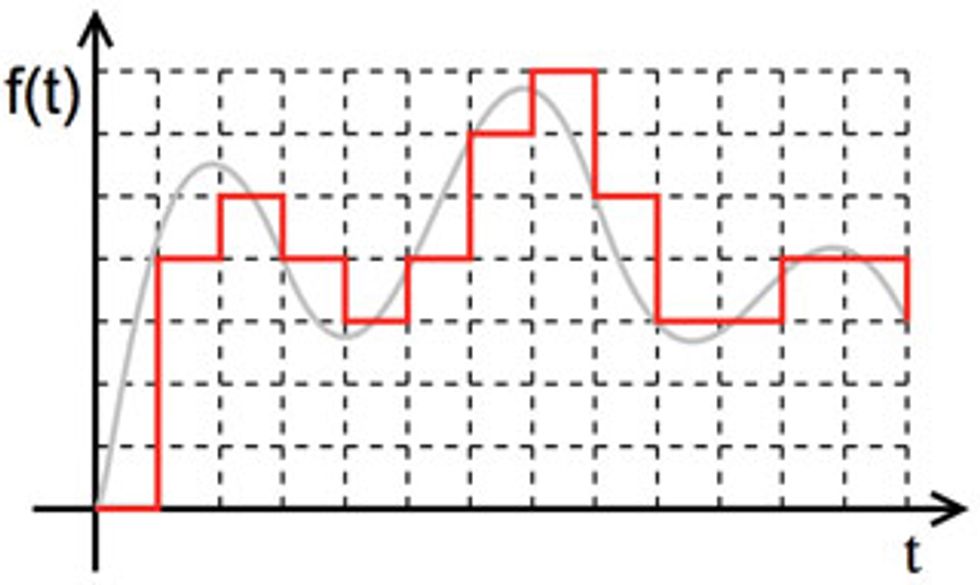

As illustrated by the smooth gray line, a sound wave is a continuous, unbroken event. In digital audio, sounds are sampled at various points, as shown by the red line. These samples are used to create a representation of the original wave.

Over beer and cheap Mexican food with Masa Fukudome, a Grammy-winning engineer and musical partner-in-crime, the conversation turned to tape-versus-digital, a topic as interesting as watching paint dry. Masa is so old-school that his email address contains “longliveanalog." Analog is warmer, bigger, more musical ... blah, blah, blah. I've heard it all and I'm telling you, the horseless carriage gets you where you want to go quicker. Computers work fast and they're accurate, clean, quiet, and cheap. Tape lacks all of these qualities. However, Masa made an interesting point that forced me to rethink recording: He argued that tape machines don't work better, musicians work better with tape.

Before I reveal Fukudome's theory of recording, let's review the differences: In theory, analog should sound better. Drop a pencil on the floor right now. That click-ick-ick-ick you hear is one continuous sound wave. Digital, by virtue of its nature, contains breaks for each sonic change, be it pitch, volume, or whatever.

Jonathan Strickland, a senior tech writer at HowStuffWorks, explains the consequences of chopping up a sound wave like this: “Some audiophiles argue that because analog recording methods are continuous, they are better at capturing a true representation of sound. Digital recordings can miss subtle nuances."

However, digital technology improves every year as digital devices use higher sampling rates. Although I don't have the science to back it up, I think of digital recording a bit like a TV or video screen. Enlarge a TV or video image and you'll see that images are actually composed of dots or pixels, yet our brain is able to fill in the missing parts. A digital recording of a sine wave may not look like its analog cousin, but our brains fill in what's missing. Unless a recording is truly terrible, most of us focus on the music, not on the subtleties of sound recording.

For most of us, the quality of a recording doesn't matter because we listen with bad gear. About 90 percent of my music listening takes place in the worst possible environment: the stock radio in my 1994 Mercury or MP3s and YouTube videos blasting from my laptop computer's cheap speakers. It must not sound that bad because I listen to music all the time. So, if digital is easier and cheaper and few of us can tell the difference, why does Masa Fukudome argue that analog remains the better way to record? Because musicians are more focused and involved when working with tape.

About seven years ago, I was recording to tape at Bayou Studio in Nashville doing some made-to-order tracks for a TV show. The producers specified that one section needed to contain 13 hits spaced roughly one second apart to correspond with a montage of 13 still photos. For some reason, our bass player—who will remain anonymous—had a difficult time playing it. After about five takes, he asked, “Can't you just fly in part of it?" To which the engineer replied, “Sorry boys, you've got to be able to play to record here." We all got a good laugh over this quip, but secretly marveled that musicians have devolved to the point where playing well isn't necessarily required.

Back in the days of magnetizing rather than encoding, we would rehearse, then track. Once we got a good take, everyone would pile into the control room and quietly listen while making copious notes on our charts. We would talk over arrangement ideas, and then track and re-track as a band until we had a great ensemble performance that was basically done. We would then add overdubs and do any fixes. Because punching in and out with tape lacks the surgical precision of Pro Tools, solos were more likely a performance then a composite of lots of little licks and phrases.

These days, I do most of my recordings alone, playing to drum loops and building tracks. When I do a band session, the process is completely relaxed. We talk it through, make suggestions, blow down a decent take, and then everyone schleps into the control room for the playback. But nobody really listens like they used to. Rather than focusing on what they played, people talk about movies or the industry. If something isn't right, the engineer can probably fix it. For solos and fills, I find myself compiling the best of three or four takes. Although this method cuts out all the wrong notes, it doesn't make for a cohesive part. We get more ear candy, less flowing melody.

Last night I listened to the Stones' Sticky Fingers, a quintessential example of a band cutting live to tape. Hearing this album was like watching a cat fall off a roof, awkwardly spinning upside down, then at the last moment landing on its feet without a scratch. The Stones would speed up, slow down, and careen dangerously around the beat, but they all grooved together. It felt like rock 'n' roll. In Keith Richards' autobiography, Life, he described their torturously long recording sessions, cutting take after take all night until it felt right. I don't know if musicians who were raised recording in the digital world could have that same work ethic.

The analog generation knew how to make music. What you heard on record was actually played by real people. The gear they used for recording doesn't really matter. I think that may be why Joe Walsh titled his new album Analog Man. I use to think analog guys were silly, preachy, and perhaps delusional, but ultimately, I get it now. Digital audio not only breaks for each musical change, digital recordings tend to be a compilation of many tiny performances that are manipulated and flown around a grid. Analog captures continuous sound—a performance committed to tape. Musicians commit to their sounds and parts, rather than getting them close enough that an engineer can make them perfect.

Perhaps the most pragmatic approach would be to combine the spirit of analog with the efficiency of digital—capture a committed performance with a clean digital system. Let's settle for that because none of the studios I use today still have a functioning 2" tape machine or remember how to use it.

John Bohlinger is a Nashville multi-instrumentalist best know for his work in television, having lead the band for all six season of NBC's hit program Nashville Star, the 2011, 2010 and 2009 CMT Music Awards, as well as many specials for GAC, PBS, CMT, USA and HDTV.

John's music compositions and playing can be heard in several major label albums, motion pictures, over one hundred television spots and Muzak... (yes, Muzak does play some cool stuff.) Visit him at youtube.com/user/johnbohlinger