Think you know every nook and cranny of the modern guitar world? Think again. Here we take you inside the burgeoning Indian lap slide scene—a place where players from one of the world’s oldest civilizations took inspiration from Hawaiians, created mind-boggling 20-string instruments, and now conjure spellbindingly virtuosic music.

It’s an improbable story: A Hawaiian guitarist ventures to India and ignites a craze for lap steel. Indian filmmakers and composers embrace Hawaiian guitar and incorporate its keening sound into their Bollywood productions. A few enterprising young musicians take note of the lap steel’s melodic expressiveness and begin modifying archtop acoustics with sympathetic and plucked drone strings, making them suitable for playing ragas—the melodic patterns and modes in traditional Indian compositions. Soon these hot-rod guitars are accepted as legitimate instruments for performing Indian classical music, and a new breed of virtuosos emerge to write yet another chapter of the guitar’s unpredictable evolution.

All this and much more actually happened, but if you’ve never heard the music spawned by this cross-cultural collision, you’re not alone. Most Western guitarists are unaware of their Indian lap-slide counterparts and the vibrant sounds they create.

In the next few pages, we’ll explore what is now known as Indian classical guitar, or Hindustani slide, and learn how the tradition continues to unfold today. We’ll hear from several leading exponents of the genre and discover what albums played pivotal roles in its development. And, of course, we’ll gaze at the mind-boggling guitars that are at the heart of this music.

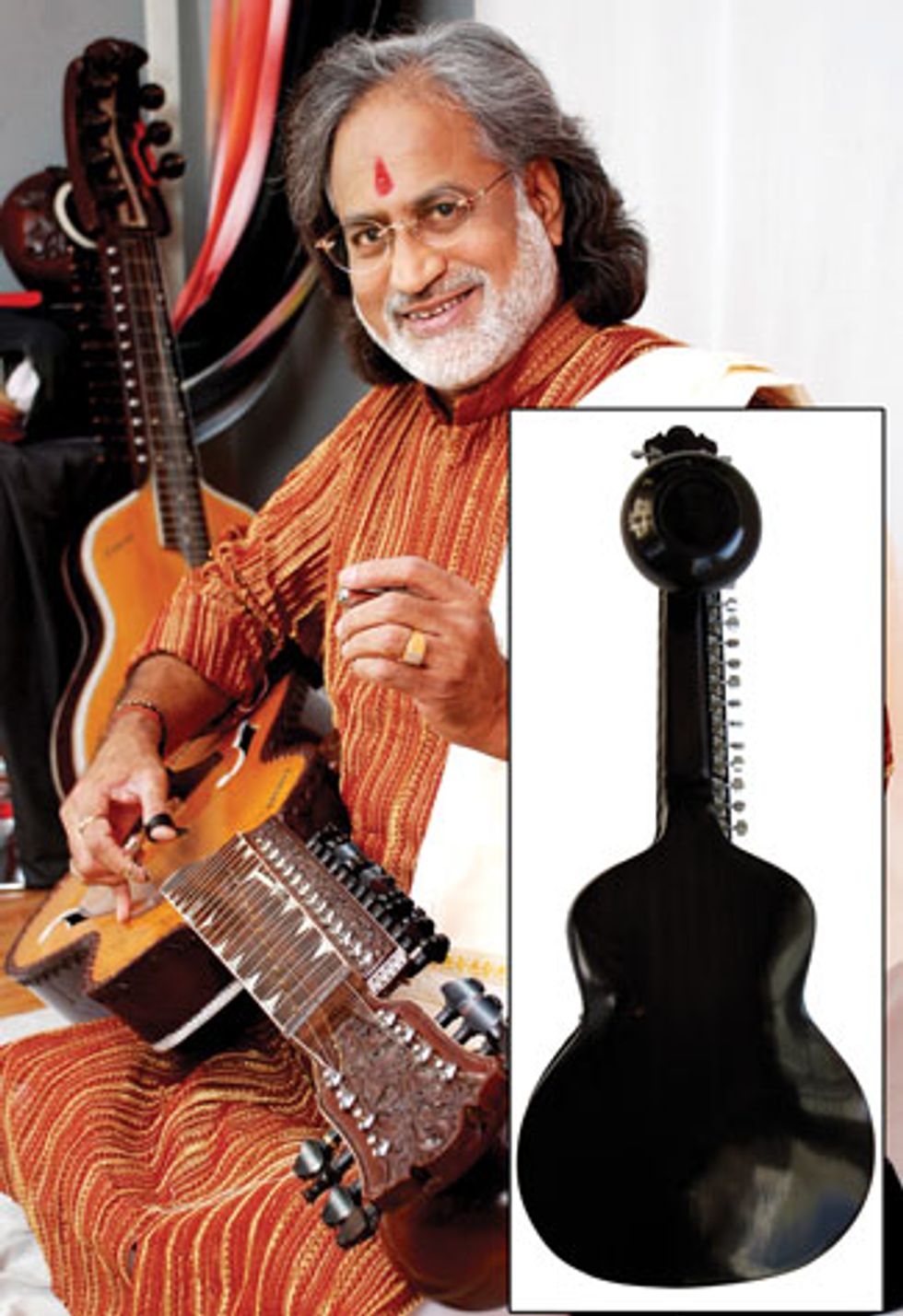

The father of the mohan veena lap slide guitar, Vishwa Mohan Bhatt (above), studied with the great sitarist, Ravi Shankar. Inset: Photo courtesy of Lars Jacobsen, Rain City Music

From Oahu to Calcutta

Like so many developments in the guitar’s history—

and this includes flamenco, Delta blues,

and even rock ’n’ roll—the genesis of Indian

slide is shrouded in mystery. Key figures in this

movement offer different interpretations of its

birth and who was the first to modify a guitar

for playing ragas.

But this much we know: It began with Tau Moe (pronounced mo-ay), the Hawaiian hero of our saga who first performed in India in the late 1920s and ultimately settled in Calcutta from 1941 to 1947. During this time, Moe and his family performed and taught Hawaiian music, and built and sold steel guitars. Many Indians—listeners and musicians alike—became entranced with the sound of steel guitar. Initially, these fans were attracted to the novelty of Hawaiian songs, but by the early ’60s, steel guitar had become a familiar sound within Indian popular music—and this remains true today, especially in film soundtracks.

Brij Bhushan Kabra was one of the Indian musicians who heard the steel’s siren call, but his vision went beyond adapting Hawaiian sounds to popular music. Instead, he saw the instrument’s potential for playing ragas. To pursue this dream, Kabra began studying with Ali Akbar Khan, whose fretless sarod offered a sonic example for Kabra to emulate with his lap-slide guitar. Kabra’s instrument was a Gibson Super 400, modified with a drone string and a high nut to raise the strings off the fretboard like a lap steel. Seated on the floor in the traditional style of Indian musicians, Kabra played his guitar horizontally, using a fingerstyle plucking technique and a bar to contact the strings. His approach set the standard for virtually all Indian slide guitarists.

In 1967, Kabra recorded a groundbreaking album, Call of the Valley. Also featuring Shivkumar Sharma on santoor, an ancient hammered dulcimer, and Hariprasad Chaurasia playing a bamboo transverse flute called the bansuri, the album was a hit not only in India, but also with the Woodstock generation who was discovering Hindustani music through sitarist Ravi Shankar. Perhaps the first studio recording of Hindustani slide guitar, Call of the Valley is essential listening for anyone exploring this music. Next Kabra released Two Raga Moods on Guitar, and though now out of print, this LP confirmed his status as the father of the genre.

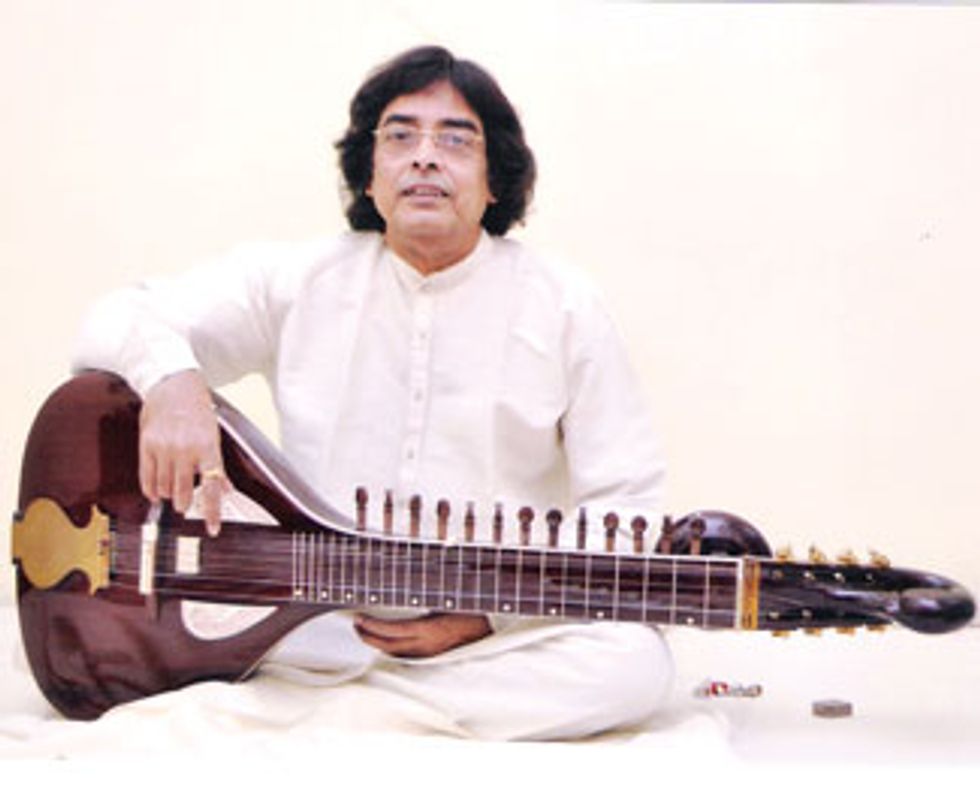

Barun Kumar Pal is pictured here with his hansa veena, a lap-slide instrument with a sitar-like body that he developed with Ravi Shankar.

Following in Kabra’s footsteps, Vishwa Mohan Bhatt (aka VM Bhatt) modified his archtop to such a great degree that the instrument became known as the mohan veena. “I conceived the mohan veena about 45 years ago,” says Bhatt. “I crafted it by modifying a stunning guitar my sister brought to India from West Germany.” Bhatt configured his guitar with three melody strings for playing with a slide bar and added four plucked chikari drone strings and 12 tarab (or taraf) sympathetic strings, which vibrate and buzz like a sitar. And that’s not surprising: Bhatt studied with Ravi Shankar and is now a senior figure in this lineage. Through Bhatt’s concerts and recordings, the mohan veena has become the de facto standard for playing ragas on guitar.

In 1992, Bhatt joined Ry Cooder in the studio, and the two created a spellbinding fusion of Hindustani slide and bottleneck blues. Released in ’93, A Meeting by the River remains one of the most artistically successful world music collaborations ever and another landmark in the history of Indian slide guitar. “Blues attracted me, as it is very close to my kind of music,” says Bhatt. “The tone of the guitars, the whole feel is so beautiful. Most importantly, the deep emotions attached to blues pulled me close to it.”

Bhatt has also recorded with other Western musicians, including Dobroist Jerry Douglas and banjo guru Béla Fleck. Bhatt’s 1995 collaboration with bluesman Taj Mahal, Mumtaz Mahal, offers fascinating interpretations of the blues canon, including the spiritual “Mary Don’t You Weep” and Robert Johnson’s “Come On in My Kitchen,” as well as a haunting version of “Stand by Me.” Bhatt’s buzzing, microtonal lines bubble below Mahal’s gravelly vocals and fingerpicked blues to create a sonic bridge between East and West.

As with Bhatt, the sitar connection runs deep with Barun Kumar Pal, another Indian slide-guitar master. Pal began playing sitar at age 5, but Hawaiian guitar caught his ear and within a year he was playing it on the radio in youth orchestras. Pal studied with both Ravi Shankar and Nikhil Banerjee, one of India’s most revered sitar players. Inspired by the sitar, Pal too began adapting his Hawaiian guitar for Indian classical music. By 1973, he’d added chikari and tarab strings to his guitar.

Then, in conjunction with Shankar, Pal developed a new type of slide guitar. With a body that more resembles a sitar or sarod, this instrument is known as the hansa veena—a name credited to Shankar—because its curving headstock looks like the neck of a swan (hansa). It has 21 strings, 13 of which are tarab. You can hear it on Pal’s 2001 release, Ragas on Hansa Veena. More recently, Pal has returned to a multi-stringed archtop, and he makes it cry on the sublime Ragas on Slide Guitar.

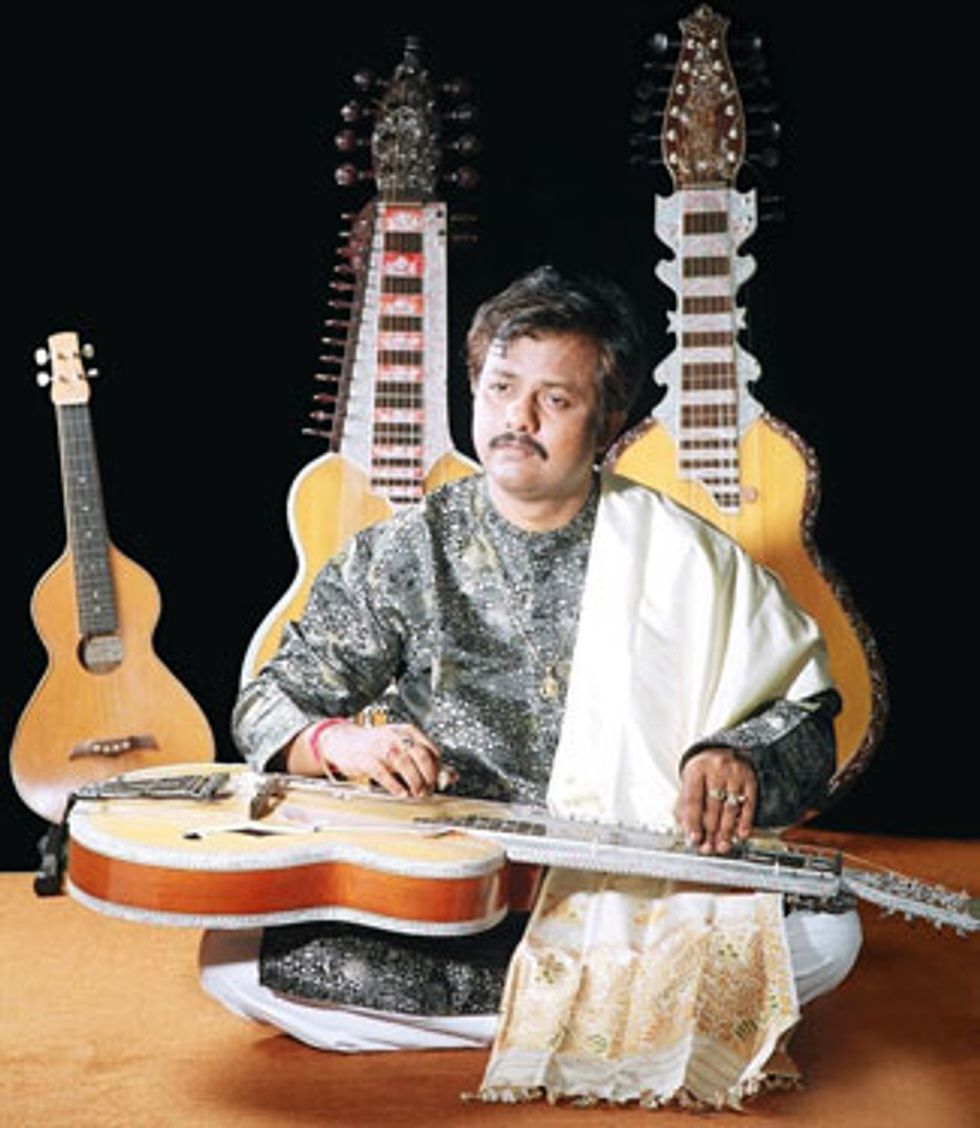

A student of Brij Bhushan Kabra, the pioneer of Indian classical guitar, Debashish Bhattacharya is a Hindustani slide virtuoso who designs his own instruments.

The Next Generation

After Kabra, Bhatt, and Pal had morphed the Hawaiian steel into

a lap-slide guitar with drone and sympathetic strings—and, more

importantly, shown that this hybrid instrument was fully capable

of expressing the subtleties of Indian classical music—a new generation

of guitarists emerged, ready to push Hindustani slide into

unmapped sonic territories.

One such player is Debashish Bhattacharya, a child prodigy who began performing at age 4 and then spent a decade studying with the great Kabra. Accompanied by his brother Subashish on tablas, Debashish tours the world, and often collaborates with Asian and Western musicians. When John McLaughlin recorded Remember Shakti, he tapped Bhattacharya to be part of the ensemble. Bhattacharya has also recorded two albums—Sunrise and Mahima—with resonator wizard and Hawaiian guitarist Bob Brozman.

Bhattacharya has released a slew of Hindustani slide albums, and his 2008 Calcutta Chronicles: Indian Slide Guitar Odyssey is a stunning example of slide-guitar virtuosity and deep musicality.

Like those before him, Bhattacharya has no inhibitions about modifying the guitar to suit his purposes. One of his creations is a 22-string archtop he calls the chaturangui. It has six primary melody strings for playing with a bar, four plucked chikari drones, and 12 tarab sympathetic strings, which Bhattacharya tunes to the tones of a given raga.

One major change Bhattacharya made to the mohan veena was to move the chikari to the other side of the guitar neck. “On all traditional plucked raga instruments,” he explains, “such as the sitar, veena, and sarod, the chikari run along the side of the neck closest to the performer, who strikes them with his thumb. But on the chaturangui, I located the chikari on the opposite side, next to the 1st string. Doing this lets me pluck the drones with my index finger, rather than my thumb, and thus play much faster passages.”

The chaturangui, as well as a hollow-neck 12-string with two chikari that Bhattacharya calls the gandharvi, are built in Calcutta and distributed by Trideb International. “These are cross-cultural instruments,” says Bhattacharya, “for jazz and blues slide guitarists, as well as those playing ragas—which we believe is not ethnic music for one part of the world, but rather global music for everyone to share.”

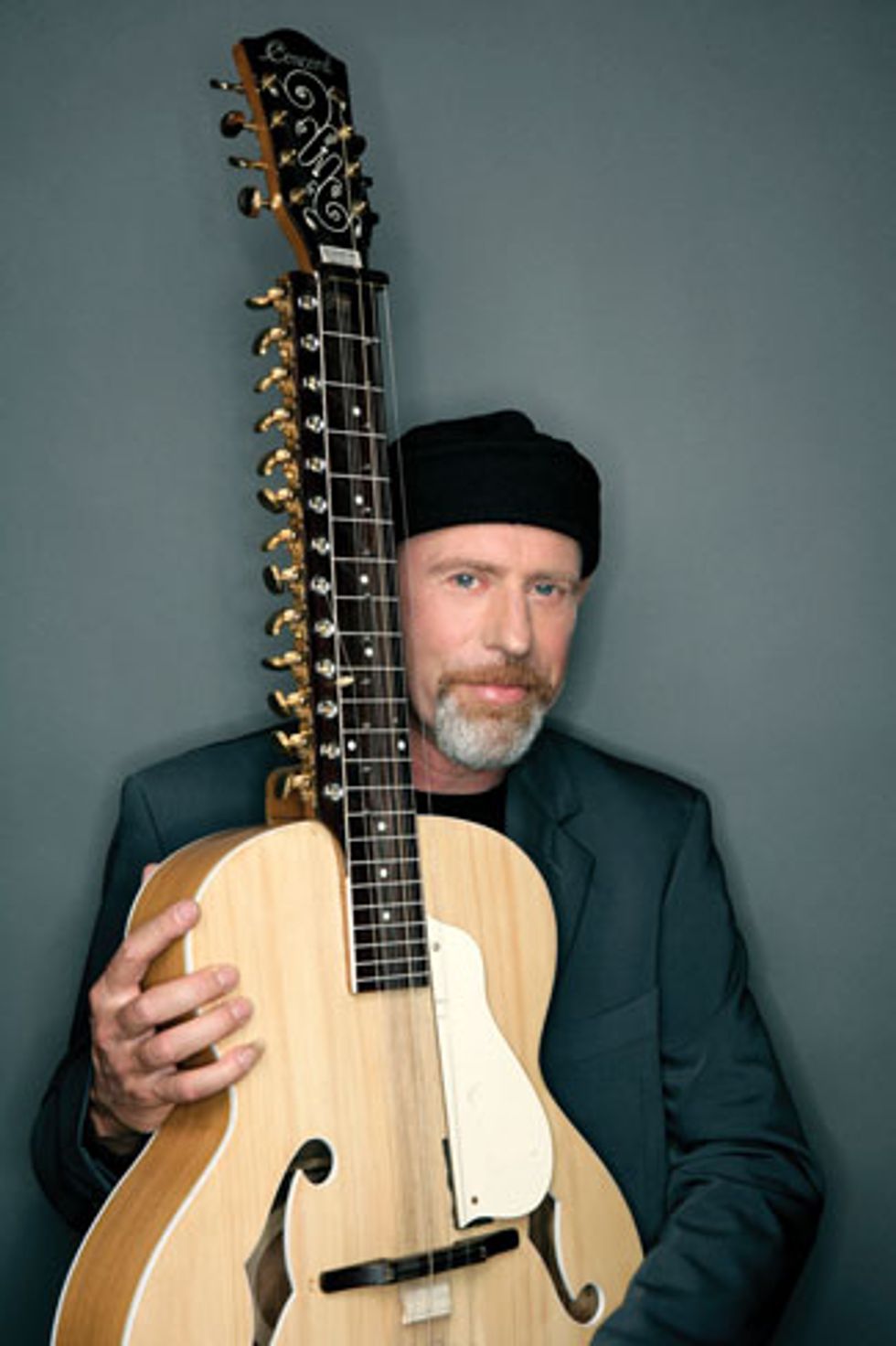

Canadian Harry Manx studied the mohan veena in India with Vishwa Mohan Bhatt.

Another next-gen Indian slide guitarist is Salil Bhatt, son of VM Bhatt. In addition to sharing the stage with his legendary father, Salil records and tours as a slide master in his own right. He plays a 20-string archtop guitar he designed called the satvik veena. This instrument has three melody, five drone, and 12 sympathetic strings. It also sports a gourd below the headstock that adds resonance and rests on the floor to support the neck in a horizontal playing position.

Like his father, Salil often collaborates with non-Indian musicians. On the two-album Slide to Freedom series, for example, he swaps runs with Dobro and bottleneck guitarist Doug Cox, recalling the epic pairing of VM Bhatt and Ry Cooder.

There are other respected and influential Indian slide players, most of whom wind up designing personal variations of the mohan veena pioneered by Bhatt. Several of these, including Shri Krishan Sharma, Neel Ranjan Mukherjee, and Kamala Shankar—the leading female Hindustani slide guitarist—are well documented in YouTube videos.

The Circle Expands

While most Hindustani guitarists are Indian, there are exceptions.

Many consider Harry Manx to be the best North American mohan

veena player. Manx, a Canadian who also plays bottleneck blues

and rootsy folk music, went to the source to learn the instrument.

“I was studying the sitar,” Manx details, “and I was also a slide player, so the mood was set for me to discover the mohan veena. Oddly enough, I was in Japan when I first heard it. I was playing on the street one day, and this magical sound was coming out of a record shop. I just stopped dead in my tracks because I realized it was slide, but it was sitar—it was everything I really loved. The musician turned out to be VM Bhatt.”

Manx tracked down Bhatt in India and began studying with the master. “VM Bhatt gave me my first mohan veena,” says Manx, “because he saw I was a dedicated student. I just came and I wouldn’t leave, so I passed the test.”

Eventually, Manx toured with his guru, backing him on tambura, an instrument that supplies the drone in classical Indian music. In the process, he gained valuable insights into how Indian musicians approach their instruments.

Essential Listening

Call of the Valley, 1967.

An enduring classic. This is where Brij

Bhushan Kabra first introduced the world

to the haunting sound of traditional

Indian music played on a lap-slide guitar.

A Meeting by the River, 1993.

The Mississippi River meets the Ganges

in this telepathically improvised session

featuring Vishwa Mohan Bhatt on

mohan veena and Ry Cooder on bottleneck

acoustic.

Ragas on Slide Guitar, 2003.

Backed by adventurous multitracked

tablas and hand drums, Barun Kumar Pal

performs an exquisite collection of ragas

on his multi-string archtop lap slide.

Calcutta Chronicles:

Indian Slide Guitar Odyssey, 2008.

Debashish Bhattacharya explores Gypsy,

Arabic, and, of course, Indian melodies

and rhythms on three different lap-slide

instruments of his own design. Creatively

adventurous and technically arresting.

“They practice their asses off,” says Manx. “Practice beyond practice. There’s a wonderful tradition of dedication in India, which we could take great lessons from here in the West. Very few of us have ever applied ourselves to this degree to our music. I did my five hours a day for five years, and that experience took me from being a really mediocre player to somebody who could sort of play decently.

“When I decided to leave India after being there about 12 years, I went to Calcutta and had five mohan veenas made. I’ve given away three—one to Jerry Douglas—so now I’m down to two. They’re both good instruments, so that’s probably enough for me.”

Hindustani slide has a rich past, but its future looks even more promising. “When I started playing Indian classical music,” says Bhattacharya, “only my guru Pandit Brij Bhushan Kabra and a few other senior Hindustani slide guitarists were performing and recording. Today, the slide-guitar fraternity around the world is aware of the technique and sound of this instrument. So much so that one can say Hindustani slide guitar is now a global instrument.”

Through his new band, Calcutta Chronicles, Bhattacharya continues to expand the genre with his brother Subashish on tabla and percussion, and his daughter Sukanya as guest vocalist. “We’ve been collaborating in the studio with such international musicians as John McLaughlin, Jerry Douglas, Jeff Sipe, and Adam del Monte,” he says.

Exploring Indian Music as a Player

If, after listening to Hindustani slide, you’re inspired to try the

mohan veena, Manx offers this advice. “To learn Indian music,

there are two aspects to consider. You can’t be a rock guitarist and

just say, ‘Now I’m going to play an Indian thing.’ Unless you simply

copy the notes from a recorded raga, you’ll need to learn something

about how Indian music works. Each raga has a set of notes

you can play, but if you want to play them properly, you need to

play them in a particular order. For instance, you might have to go

from 1 to 3 to get to 2. If you follow that order, you start to get an

Indian sound and what you play begins to make sense.

“The second consideration is how you approach notes. In Indian music, it’s really important to know whether you slide up to a note, slide down to it, or hit it right on. Or do you slide up to another note and then come back to the note you want. How you approach the note is called the meend, and to get a sense of this, you need to get records of Indian slide players and really listen to how they approach notes, because that’s the key. It’s the same in blues—B.B. King has a wonderful meend. He plays two notes and you know it’s him.

“So there’s what to play—the raga side—then there’s how to play it, which has a lot to do with the meend. These are the two aspects of Hindustani slide you really want to look at.”

Going Beyond the Guitar

Whether you want to actually play a mohan veena or simply expose

your ears to new melodies and rhythms, the world of Hindustani

slide can provide a lifetime of creative inspiration. Perhaps

Bhattacharya sums it up best: “I have always told myself that music

has no boundaries. As you may know, Indian music has a link to

universal awareness, and this helps me understand the innermost

meaning of music from other cultures. My entire existence is dedicated

to working with musicians all over the globe, and—at any

place, at any given time—expressing the rasas [essence] of the nine

unique human moods.”

If you’re drawn to Hindustani slide guitar, it’s worth remembering that at its core, this music is about transcending daily consciousness to experience an altered state. This is the goal for Indian musicians, as well as their audience. “Onstage,” Bhattacharya reveals, “when I get deep into the raga, I forget everything. First, I forget where I’m sitting. Then I forget what I’m doing. And, finally, I forget my name and who I am.”

YouTube It

To fully experience Hindustani slide, you really need to watch

a master at work. These videos reveal not only the incredible

virtuosity of these guitarists, but also the emotional forces

they can conjure from wood, wire, and a steel bar.

Accompanied by Subhajyoti

Guha on tabla, Barun Kumar

Pal performs a haunting

raga on the hansa veena in

this 2008 performance.

Artful camerawork allows

us to hover over VM Bhatt’s

mohan veena and get a

clear view of his bar work

and fingerstyle technique.

VM Bhatt and his son Salil

trade blistering lines on the

mohan veena and satvik

veena in this 2009 festival

performance.

Debashish Bhattacharya

plays three different slide

guitars of his design—the

massive chaturangui, the

gandharvi, and tiny anandi.

His virtuosity shines on each.

In this rare British television

broadcast, the guitarist who

started it all—Brij Bhushan

Kabra—plays his modified

Gibson Super 400 onstage

backed by Zakir Hussain.

Harry Manx sings Van

Morrison’s “Crazy Love”

while accompanying himself

on the mohan veena.