Learn some common Western swing progressions and turnarounds to help you dive into this sub-genre of country and jazz.

Chops: Intermediate

Theory: Beginner

Lesson Overview:

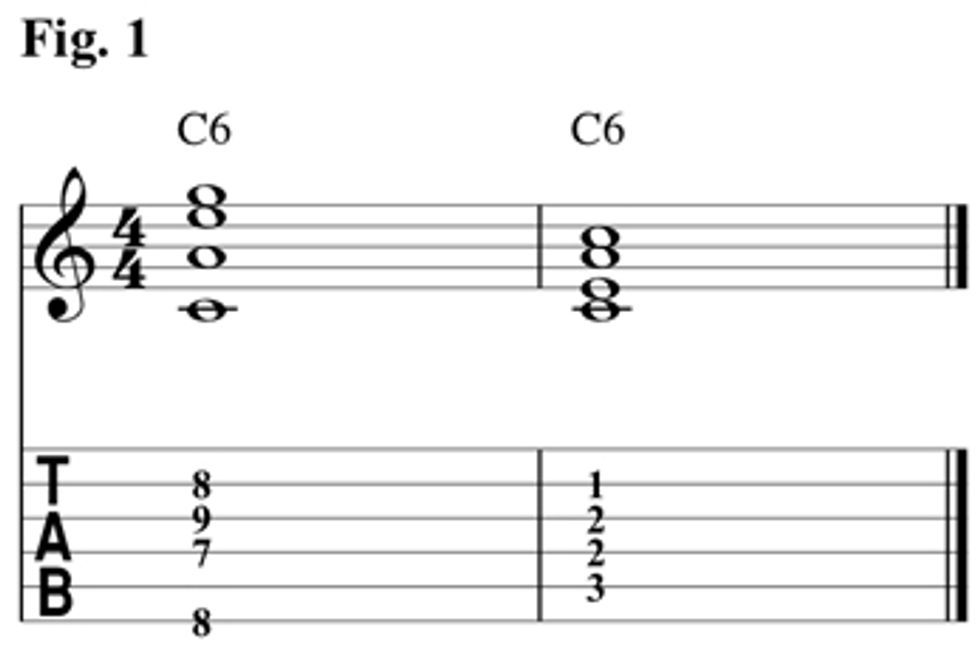

• Learn common major 6 voicings.

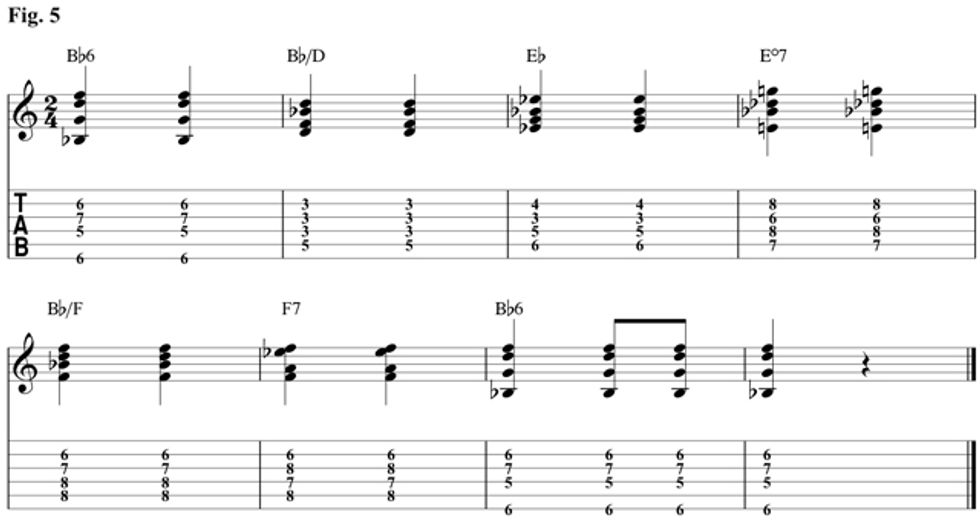

• Understand how to use passing chords to make progression more interesting.

• Use chord inversions to create movement.

Western swing has always been widely considered a sub-genre of country music, but I’ve never understood why it doesn’t get included in the jazz lineage. Western swing started to gain popularity in the 1920s. It was the South’s answer to big-band music, minus the horn section. Apparently, you couldn’t buy a trumpet in Texas in the ’20s. The role of the sax section and the trumpet section had been replaced with a fiddle and a lap steel guitar. This made lap steel guitar one of the most popular instruments in America, and it’s the reason Leo Fender started his little guitar company. There were other strong influences besides jazz and swing. Polka, folk, cowboy, and blues were all represented in the sound and song selection. Western swing thrived as up-tempo dance music played in halls and nightclubs until the 1940s, when its popularity started to fade.

Important rule number one! All major chords are now major 6 chords. This is one of the trademarks of Western swing comping. In Fig. 1 there are two C6 chord shapes that will get you pretty far. The first one has the root on the 6th string and the second shows a grip with the root on the 5th string. To make a major 6 chord, you’ll need to incorporate the 6th of the scale into the major triad. In this example, I’m using different arrangements of C–E–G–A. You might wonder, aren’t those the same notes as in an Am7 chord? Yes, that’s true! Major 6 chords use the same notes as the relative minor, in this case A minor. Context is everything though, and your bass note determines how the rest of the harmony will be interpreted.

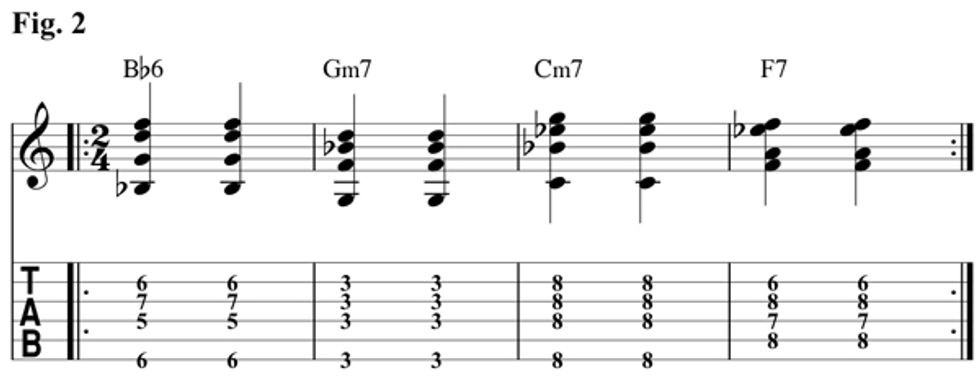

A good amount of Western swing music is in 2/4. This means two quarter-notes in a measure rather than four. Fig. 2 is a common I–Vim–IIm–V Western swing progression in Bb. I don’t let any of the chords ring into each other. I do this by pulsing the beat with my fretting-hand, and releasing string tension between attacks. Also, aim for the lower half of the chord on beat one and the upper for beat two. The low/high treatment with the pulsing puts a nice little bounce in the rhythm.

One of the things I love about Western swing is how melodic you can be with bass lines by adding some passing chords. Fig. 3 is a I–IIm–V progression with a passing chord before the IIm chord. Our passing chord will act as a dominant chord and will set up the IIm–V progression while adding chromatic movement to the bass line.

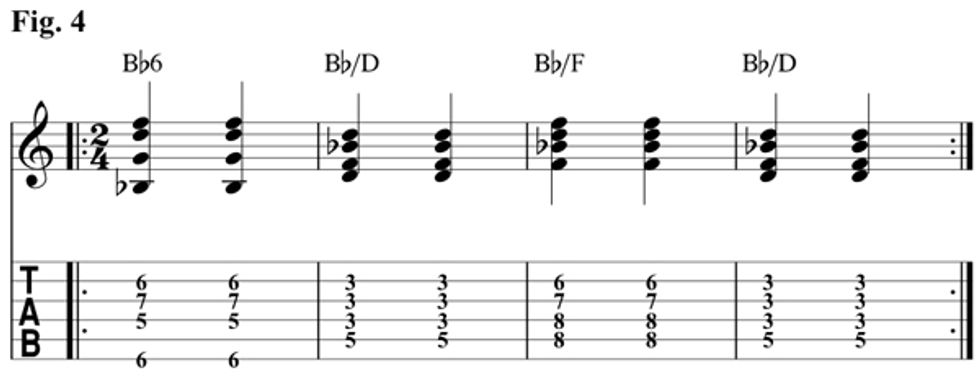

Don’t just sit there! If you’re hanging on a chord for any length of time, make sure to move that sucker around. Chord inversions imply change when the harmony is static, so you can take advantage of this to create some motion. In Fig. 4, I start with our standard Bb6 voicing and then move through a few inversions of a Bb triad. Inversions of the major 6 chord don’t translate as strongly as inversions of the triad.

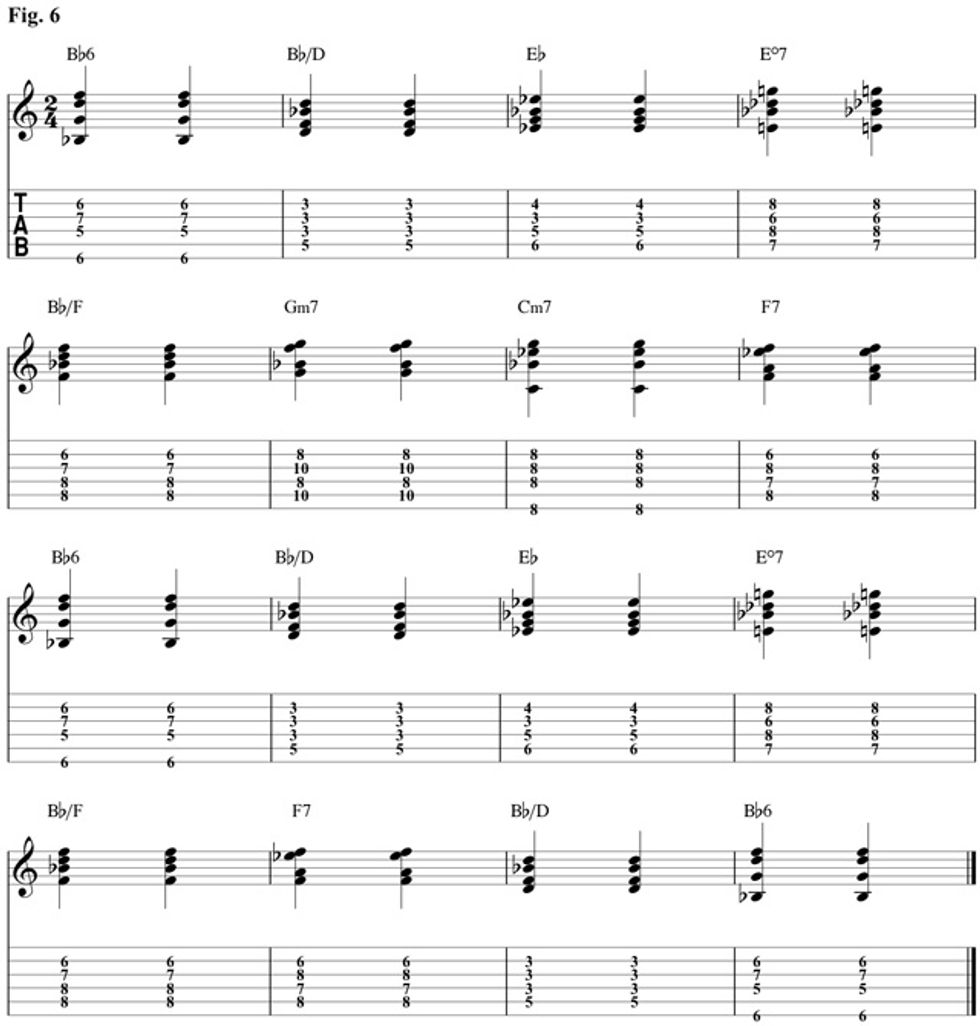

Fig. 5 is a common turnaround full of passing chords and chord inversions. If I strip away the inversions and the passing chords it’s really just I–IV–I–V. Without the passing chords the progression is pretty boring but with a few minor changes we now have a catchy bass melody and some forward momentum. We put everything together in Fig. 6. This progression comes from a tune called “Comin’ On” by one of my heroes, Jimmy Bryant.

There are a lot of good box sets and compilations if you’re looking to dive right into the world of Western swing. The really important bands to check out would be Bob Wills and His Texas Playboys, the Light Crust Doughboys, and Spade Cooley & His Orchestra. Swing on!