Dubbed “the Hendrix of the Sahara,” Vieux Farka Touré talks about growing up in the shadow of a famous dad, his unique two-fingered strumming approach, and having Dave Matthews and John Scofield join him on his new album, "The Secret"—one of the freshest-sounding guitar albums of 2011.

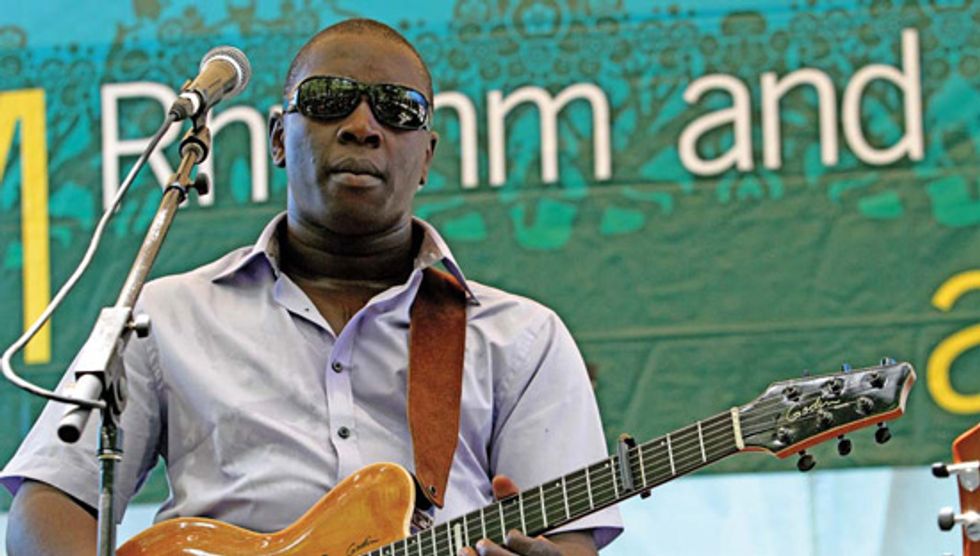

Vieux Farka Touré capos his Godin Summit CT and hits a joyous

chord during a gig in Sydney, Australia. Photo by Daniel Boud

Understanding a genre’s lineage helps you connect dots over time to understand how music interconnects and evolves. Nothing illustrates this better than the blues, whose evolution can be traced through many different generations and geographic regions. You can see the progression from America, beginning with the earthy Delta style of players such as Charley Patton and Robert Johnson, and then Muddy Waters helped morph it into a gritty, urban blues, and before long the genre had hopped over the Atlantic to the UK and led to the high-energy solos of Eric Clapton and the dirty swagger of the Rolling Stones. The cycle will keep going in perpetuity—especially with the ease of global information transfer that technology affords today—and all of it will continue to inform modern blues and blues-rock. The Secret, the latest release from Malian guitarist Vieux Farka Touré, is a great example of this.

Although we all know the blues blossomed as a cathartic American art form fed by the blood-and-sweat-soaked soil of slavery, poverty, and prejudice, if you go back before Johnson’s supposed meeting at the crossroads and Patton’s siring of the Delta blues, you logically end up in Africa—the homeland of the mothers, fathers, and grandparents of the genre’s founders. And naturally, the cycle of musical evolution goes back in time to the dawn of humankind.

As Darwin found on the Galápagos Islands, though, the same species will evolve differently under contrasting conditions. And for players interested in how this phenomenon has played out musically in modern times, Vieux Farka Touré’s father, the late Ali Farka Touré, has proven a fascinating and enjoyable study. Ali’s first appearance on the world music scene came with his 1976 album Ali Touré Farka, and soon after his reputation as an “African John Lee Hooker” spread throughout the continent. Prior to succumbing to bone cancer in 2006, Ali’s influence had spread into the mainstream due to his collaborations with slide wizard Ry Cooder, Taj Mahal, and Corey Harris.

Touré onstage with percussionist Souleymane Kane (left) and

drummer Tim Keiper (middle). Photo by Daniel Boud

Considering how accomplished and influential his father was, it comes as no surprise that Vieux has a compelling musical story as well. Combining an extremely intricate sense of rhythm with a percussive open-string attack, Vieux stepped out of his father’s shadow with his self-titled 2007 debut. He built upon the boogie style Ali was known for and added his own Hendrix-ian influences to create a unique style with blueslike tones and repetitive song forms that stayed true to his folksy Malian roots. The album featured a guest spot from his father, and Toumani Diabaté— who plays kora [a 21-string African instrument that’s like a cross between a lute and a sitar] who was an important early influence and mentor to the younger Touré—also appeared on the album. Buzz started to build after the release of Vieux’s second studio album, Fondo, and his energetic and infectious live shows won him fans all over the world, as well as an invitation to play the opening ceremonies of the 2010 FIFA World Cup in South Africa. The worldwide viewership of this appearance was reported to have been close to a billion people. Not bad for a bluesman from the desert.

With The Secret, Touré wanted to create an album that captured his unique brand of African boogie without pushing it too far into the mainstream. He brought on Soulive guitarist Eric Krasno to produce the album, and invited A-list guitarists such as Dave Matthews, John Scofield, and Derek Trucks to participate. “The original idea was to have a bunch of guests on the album,” says Krasno. “The more we listened, we decided we really didn’t want to pull him out of his zone. We wanted him to do his music.” Seconds into the opening track, “Sokosondou,” you hear what Krasno is talking about: Despite the famous cameos, this album definitely doesn’t sound like it was put together by a marketing genius trying to pull a “Smooth”-style Santana move. This is Vieux’s music, done his way.

The majority of this album was recorded in Mali. What were those sessions like?

Tiring [laughs]. We did a lot of work in a very short amount of time for those sessions. I wanted everything to be in place before I left for New York to finish the album. It was a lot of fun, but it felt like a huge amount of hard work. The sessions had a very smooth and natural feel, which made the hard work inspiring.

Was this material written specifically for this project or were these songs written over a long period of time?

Both. I had been working on this project since I recorded my first album [Vieux Farka Touré] in 2005. I have always had this type of album in mind as I was writing and collecting material.

Do you usually begin with a guitar riff or a melody when composing?

I begin usually with a guitar riff. Sometimes there will be a melody in my head that comes out of nowhere and I’ll start writing down a whole song before I touch a guitar. It really never happens the same way twice.

“I wanted this album to push guitar music forward and challenge other

guitarists to come into my world,” says Touré. Photo by Phil Onofrio

Had you ever worked with Eric Krasno before this?

No, but we knew each other. It felt like a perfect fit from the beginning.

Was it a conscious decision to have a guitarist produce the album?

Yes. I wanted this album to push guitar music forward and challenge some other guitarists to come into my world.

Speaking of other guitarists, you have a few guests joining you. How did you decide on whom to invite?

My manager put a list of possible guest guitarists together that I approved. Then Krasno invited them and they said yes right away—it was that simple. What an honor it was to play with these great musicians. I have enormous respect for John [Scofield]. Though we only played together for a short time, he showed me a kind of patience on the guitar that I really appreciate and I will carry with me from now on.

What did Dave Matthews bring to “All the Same”?

He brought his own soul to the song. He understood what I was expressing in it and he developed that idea into something that larger audiences can understand and appreciate. He is a huge talent and I am so thankful that he has blessed this song.

You have a great fuzzy tone on “Borei.” How did you record that in the studio?

I played around with the Roland JC-120 Jazz Chorus and my Boss SD-1 [Super OverDrive] until I got just the right sound. I think they made it a bit brighter when they mixed the album.

Touré employs his unique two-finger picking style on his Godin Summit CT.

Note the plastic fingerpick worn on his index finger. Photo by Derek Beres

What gear did you use for the sessions?

For the sessions in Mali, I used my Godin Summit CT through the JC-120. Other than the SD-1, the only other effect I used was a Boss CH-1 [Super Chorus]. During the New York sessions, the studio had a great Mexican-made Strat that had Seymour Duncan Antiquity pickups. I plugged that into a vintage ’68 Fender Super Reverb.

What was the biggest surprise during the sessions?

I think hearing Dave Matthews’ verse was the most surprising. I knew he was a big star and would do something nice on the song, but I had no idea he would capture the spirit of the song and launch it into the stars the way he did. I was blown away.

How does improvisation factor into your performances?

My style is based in improvisation. New songs usually come to me as I improvise. Live, the songs never sound the same as they did the last time. It’s about creating a base for soloing and improvising, so for me it’s very important to allow space for things to change and for new things to come into the music. For example, “Lakkal (Watch Out)” was completely improvised in the studio with Krasno, Tim Keiper, and Eric Herman—my manager and occasional bass player. We just sat down and started jamming on some ideas, and before we knew it we had this new song. On the album, that song is right next to others that took years to evolve.

Touré onstage with Mamadou Sidibe, who’s laying down a groove

with his Samick Corsair 4-string. Photo by Daniel Boud

You have a deep connection to blues music. Do you remember when you first became interested in it?

I can’t say, since I feel like it was before I can remember. I grew up listening to my father’s music, so it’s in my blood and my soul. I don’t consider it an interest as much as an expression of who I am in my soul.

Did any other Western artists significantly influence you?

Yes, Phil Collins and Bryan Adams. They write beautiful melodies. I have always appreciated that since I was a child.

As a musician, what were your early years in Mali like?

I started playing guitar when I was 20 at the Arts Institute in Bamako [capital of Mali]. During that time, I kept my playing a secret and basically taught myself. I was afraid to let people know that I was doing it. As the son of the best guitarist in the history of Mali, I needed to be careful. Eventually, people started finding out and I began to play in Toumani Diabaté’s band. Toumani was my mentor and turned me into a professional.

Touré usually plugs his go-to Godin into a Roland JC-120 Jazz Chorus. Photo by Derek Beres

Your right-hand technique is unique. Is that something that developed naturally or did someone teach you that?

It developed naturally. It’s simply the guitar style from the north of Mali. I use only two fingers—and really all that people usually hear is one finger, the one that is doing the soloing.

Did you have any other formal musical training?

I had played percussion since I was a child. Growing up in Niafunké [in north-central Mali], I played behind both my father and Afel Bocoum. But I had no training on guitar until I joined Toumani’s band.

The title track of this album is a duet between you and your father. What was it like growing up as the son of a legendary guitarist?

Growing up, I didn’t know he was a legend or even a big star until I traveled with him to Paris. I was 10 or 11 years old and it was amazing to see the huge crowd revering him. I always knew that I was very fortunate to have him as a father. He was everything to me. He still is.

How did his music influence you?

I don’t consider it an influence. It is a base. You don’t think how the meat influences a hamburger, or how the broth influences the soup—that is the base, and then other things can come on top and influence it.

Touré plucks away on a Mexican-made Strat while in the studio. Photo by Trevor Traynor

Vieux Farka Touré's Gearbox

Guitars

Godin Summit CT, ’90s Mexican-made Fender Stratocaster, Taylor GS8

Amps

Roland JC-120, 1968 Fender Super Reverb

Effects

Boss CH-1 Super Chorus, Boss SD-1 Super OverDrive

Strings

D’Addario .010–.047 sets

Secret Sessions

Producer/guitarist Eric Krasno and jazz legend John Scofield let us in on The Secret.

Choosing the right producer for a project can be tough. You want someone who understands your musical vision but pushes you somewhere you can’t get to on your own. For The Secret, Vieux Farka Touré chose Soulive guitarist Eric Krasno. Though they hadn’t previously worked together, the connection was there from the outset. “I was a fan of his father, for sure,” says Krasno, “I heard about [Vieux] through his manager, Eric Herman, who is also a bass player and musician.”

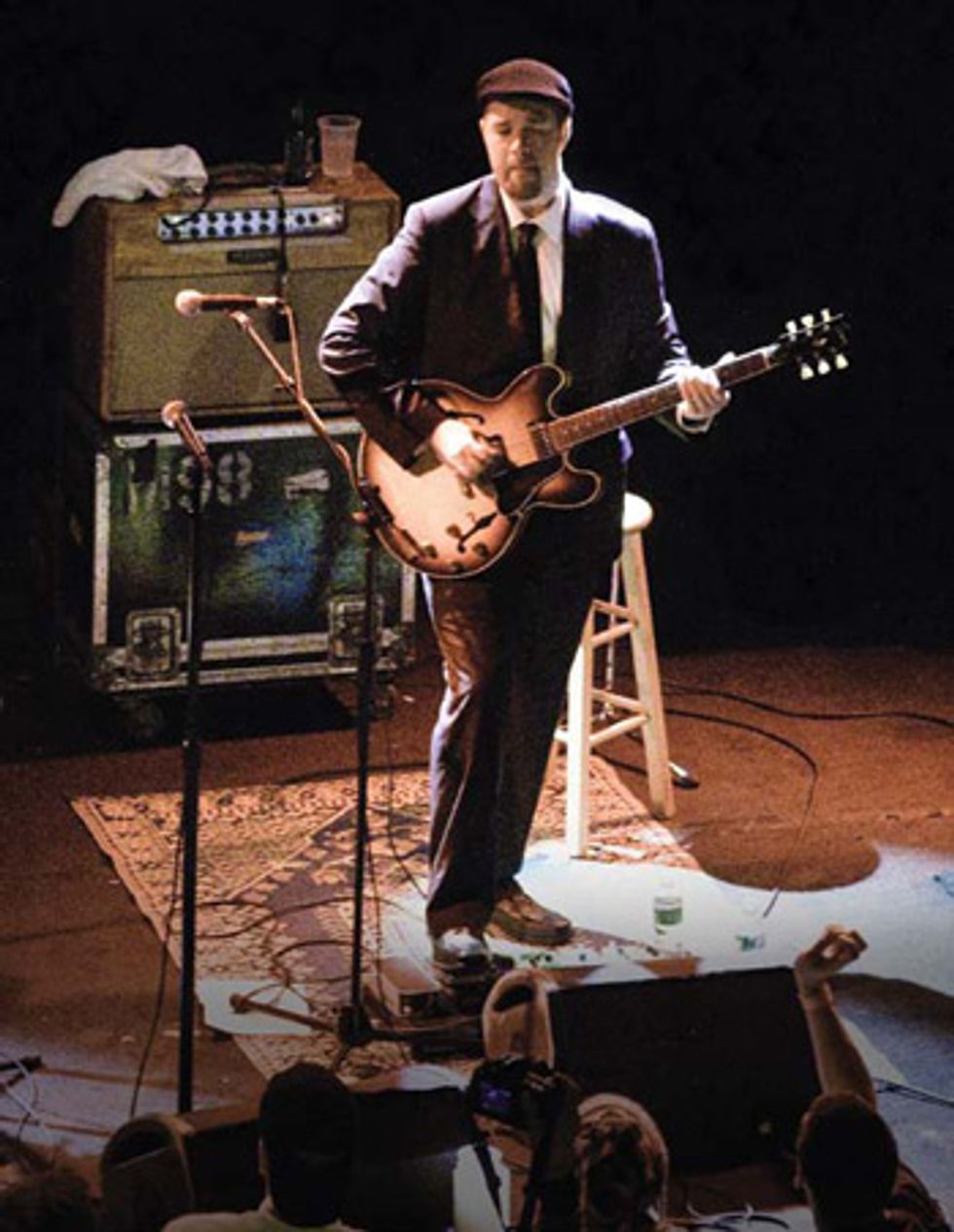

Eric Krasno lays down the funk at a Soulive gig with his Gibson

ES-335 plugged into a Mesa/Boogie Lonestar combo.

Because Vieux is based in Mali, most of the preproduction was finished before the two met at a Brooklyn recording studio. Krasno and Touré traded digital files back and forth to get a better idea of the direction they wanted to take. “I would say that 70 percent of the demos were done in Mali. We would send them back and forth, and I would listen and give my feedback.”

The title track is a duet between Vieux and his father, Ali Farka Touré. Krasno was careful not to embellish the original track too much. “We were going to revamp it and add some different instrumentation. In the end, we decided to add a little percussion, but for the most part we left it how it was and just mixed it.” Although many of the demos were tracked before the sessions in Brooklyn, that didn’t prevent them from trying to capture some in-the-moment magic. “There were a few tracks that we just recorded fresh in the studio—including ‘Lakkal (Watch Out),’ which I played on. That was pretty much one take in the studio, and turned it into a song. We used a few different ways to get from A to Z on this record.”

Because Krasno and Vieux are no strangers to improvisation, getting the right performance was more a matter of getting the right vibe than a note-perfect take. “Vieux’s approach to recording was all about ‘catch the magic.’ He would rather spend the time cleaning it up and adding overdubs than recording more takes, if he feels like the magic is there,” says Krasno.

Bona fide jazz-guitar legend John Scofield—who joined Vieux on “Gido”—came to the project through Krasno. Sco wasn’t familiar with the younger Touré, but he was already interested in music from the region. “I have been aware of North African music and its similarity to blues. I read some treatises from academic guys saying that a lot of blues sounds come from Mali. When I heard his father, I just loved it,” says Scofield. When he arrived at the session, the track was mostly complete. “It was very natural for me. On my solo, I used a 1974 Gibson ES-335 with a Bigsby going into a DigiTech Whammy pedal and a Bad Cat amp. I did a faux-Eastern sort of thing that is very much related to my blues approach to guitar. It felt right just to play. In other words, I didn’t even have to know the tune. The music felt very much at home for me.”

Krasno says he wanted to push Vieux to go out of his comfort zone when it came to gear so that the tones would be different than on previous albums. “I had him use a Jerry Jones sitar on some stuff. You can hear that in there,” mentions Krasno. “It sounds like a guitar with a weird phaser pedal. We also used a cranked 1968 Fender Super Reverb for some of the more distorted sounds you hear. He really likes using a chorus pedal, too, so I was trying to pull him away from it. We recorded at this place called The Bunker Studios, and John Davis, the engineer, had a lot of tricked-out weird stuff. I would say the primary gear was a ’90s Fender Strat through the Super.”

Throughout the sessions, Krasno got an up-close view of Touré’s style and even picked up a few things. “Every time I work with a new person, I take a little piece of that with me,” he says. “His rhythm and how he hears it is just amazing. On some of the tracks, he would count them off and I would hear them in a totally different place. His innate feel is just in a different place from where I am at—but at the end of the sessions, I knew where that was.”