In the vintage guitar business, we often hear the complaint that rich collectors have pushed prices so high that the finest guitars have been taken out of the hands of

In the vintage guitar business, we often hear the complaint that rich collectors have pushed prices so high that the finest guitars have been taken out of the hands of deserving musicians. This is hardly a new complaint. It’s been circulating for almost 200 years, ever since the emergence of violin collectors in the early 1800s. And the argument was as groundless then as it is now.

Let’s address the last part of the argument first. Are musicians really deserving of these instruments? Well, yes and no. We would all like to hear the finest musicians playing on the finest instruments, of course. But some of the greatest musicians have been among the biggest abusers of guitars—at least from a vintage collectible standpoint. They’ve routed and drilled and refinished and renecked and modified instruments until there’s no originality left, and the only vintage value of the instrument is its celebrity association.

We really shouldn’t vilify musicians for that sort of treatment. After all, in most cases they’re just being pragmatic. As professional musicians, they have to make a living with their instruments, and the instruments must be up to the task at hand. Often, the instrument had no significant value at the time they had their way with it. Nevertheless, musicians often customize instruments in ways that destroy originality.

|

Who replaced those necks and made all those other modifications to the Strads? It wasn’t the collectors. It was musicians and their repairmen. Sooner or later, as musical tastes and styles change, the same thing would happen to virtually every guitar left in the possession of working musicians. Musicians should not necessarily be vilified for this, because few would knowingly damage a valuable instrument. More often, they are merely “upgrading” a utility instrument that later becomes collectible.

Ironically, the same group who “damaged” vintage instruments were also the first to recognize their value. It was musicians in the early 1800s who discovered that older Italian instruments sounded better than new factory-made violins, and it was musicians in the 1960s—people like Mike Bloomfield, Eric Clapton, Jimmy Page and Stephen Stills— who discovered that some of the older Martins, Gibsons and Fenders sounded better than new ones. Their preference for older instruments caused other musicians and fans to appreciate these instruments and created a desire to own them. As the vintage market grew, the activities of collectors and dealers rooted out many instruments and actually put more good instruments into circulation than they removed.

It’s a short step from owning a special item to wanting to protect it, and that’s where the accusation begins that collectors take instruments out of circulation. It’s true, but only to a point. Owners of valuable violins routinely loan them to musicians so that they can be appreciated by the masses. The nature of rock and roll performance makes this a more dangerous proposition for a Les Paul or Stratocaster than for a Strad in a symphony setting, but owners of great guitars generally like to hear them played.

The late Scott Chinery, for example, had a fabulous collection that he kept in glass display cases, but when he hosted a party to celebrate his Blue Collection of commissioned archtops, he opened up those display cases to provide such notable guitarists as Tal Farlow, Arlen Roth, Jimmy Vivino and G.E. Smith with instruments for a jam session. He also sponsored recordings that used his instruments. So while Chinery may have taken instruments out of general circulation, he by no means retired them.

In addition to protecting instruments, collectors make a great contribution in the area of education. Their passion has driven much of the research that has been published on vintage instruments. Many of those who criticize collectors might never have heard of their coveted instruments in the first place had it not been for collectors’ educational contributions.

The biggest complaint about collectors is that they drive prices up. That’s true, but that’s the nature of any open market where demand exceeds supply. Collectors can’t do anything about it, nor can dealers. The upside of rising prices is that they protect the instruments, because instruments with no value get no respect.

As a final note, let’s imagine what would happen if disgruntled musicians got what they wished for, and all the instruments in collections were released. Musicians would either use them as utility tools, further damaging them, or take better care of them and put them in protective custody. In the latter case, musicians would then become their own worst nightmare: collectors depriving deserving musicians of fine instruments.

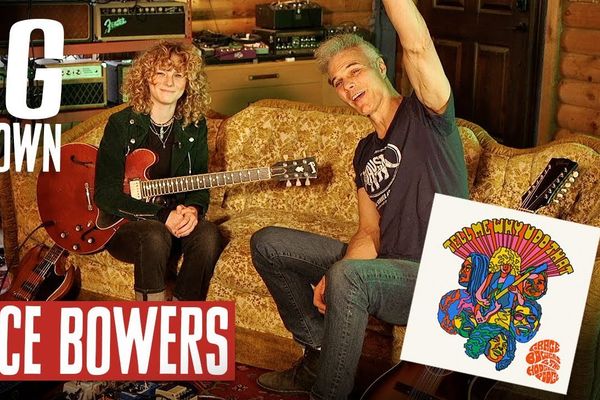

George Gruhn

has been dealing vintage guitars since the 1960s. Gruhn’s Guide to Vintage Guitars (co-written with Walter Carter) is the “bible” for vintage collectors. Visit www.gruhn.com or email gruhn@gruhn.com.