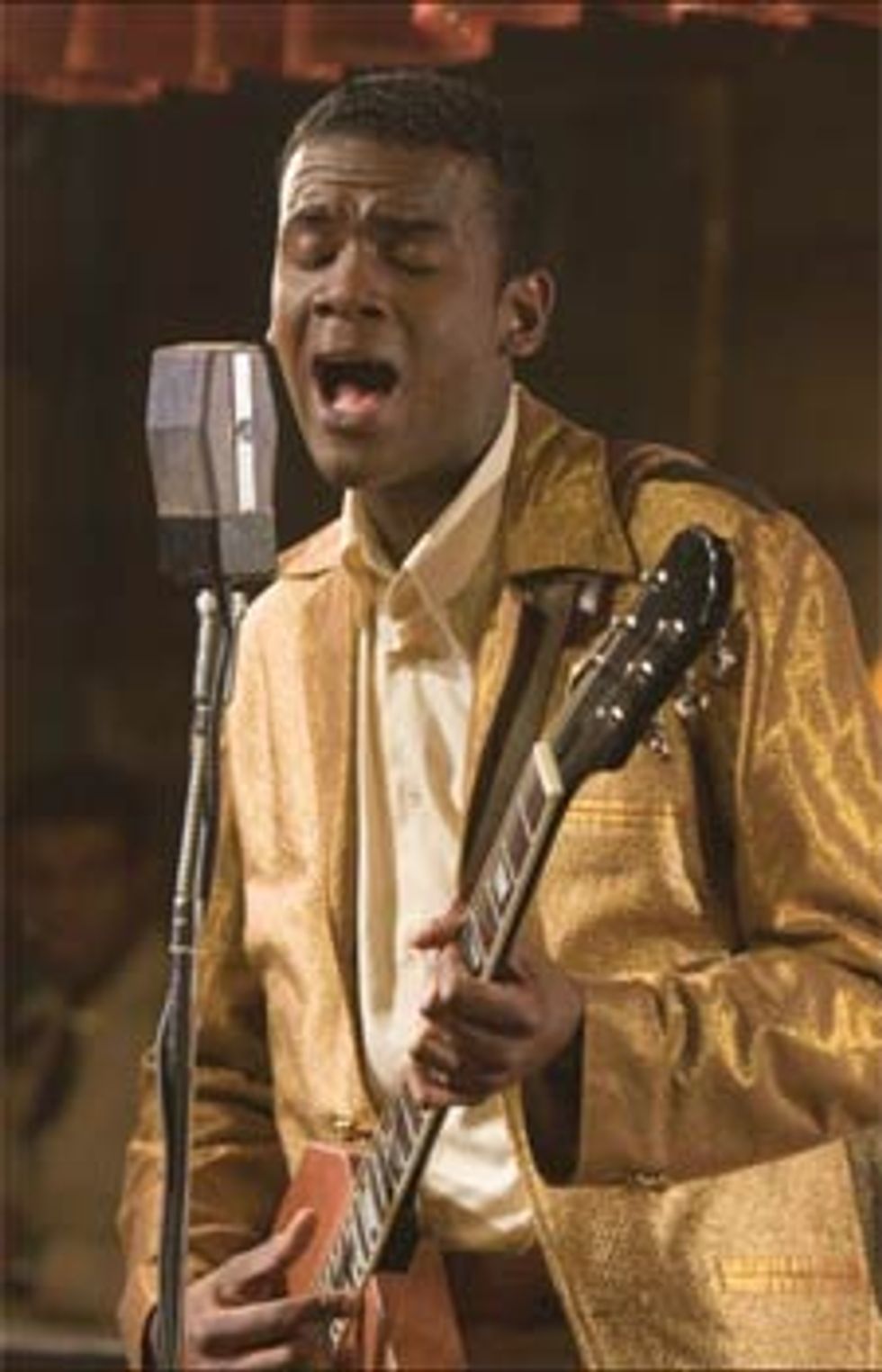

This month Brittany sits down with famed director, John Sayles, who recently released his latest film "Honeydripper." The film revolves around the 20th century musical shift in the south from piano-based to guitar-heavy blues.

|

|

|

Sayles did a tremendous amount of homework for the film. The independent director, whose only for-hire work was for Bruce Springsteen, spoke with Premier Guitar about the guitars used in the movie, guitarists that inspired the film, directing guitarists Keb Mo’ and Clarke, Jr., and the role of music during times of change.

|

|

|

Honeydripper really came out of this long relationship I have with American music. I have this feeling that we integrate, we move across racial and ethnic lines in music before anything else. Before people are really ready to look each other in the eye, they’re listening to each other. So music has been really important to American culture.

When I grew up, I listened to Top 40 radio and didn’t ask any questions. In my midteens I started realizing that rock n’ roll came from some place. That got me thinking about what it was for the players when that solidbody electric guitar showed up – that little bit of technology allowed the guitar player to take the stage from the piano guy. All of a sudden, you’ve got this guitar and more places are electrified because of Roosevelt’s TVA [Tennessee Valley Authority]. I think there was a feeling on the part of musicians about, “This whole thing is going to change really fast,” and, “Can I get onboard or do I get left behind?” I think that’s interesting to think about – what happens when people realize there’s something threatening about this change.

Exactly. There is a scene where Glover is downtown and he is starting to put everything together with Guitar Sam. The guitar comes in and you see that Glover is exhausted; he’s contemplating what’s going on.

Yeah, I think what it is – he’s 50-something in 1950; he’s grown up with the music. He was there for all that New Orleans jazz, the Ma Rainey era in the thirties and the swing era in the forties, and now he’s playing boogie-woogie piano; but can he really make this next big leap? A lot of people – like the jazz guys – just wandered away. Other people figured, “I can play this stuff – it’s not much harder than what I’m already playing. Do kids want to see a 45- year-old piano player?”

And is it professionally? Certainly people can always play music – they played folk and didn’t get paid for years, but if you’re a professional, what do you do? Do you play stuff you don’t like? Robert Johnson probably sat on a street corner and sang “White Christmas” at some point because it was just whatever the people paying wanted to hear. But does it feed you? For [Glover], the music has meant something to him – but is he willing to follow it to this new place?

Going with that younger crowd, what was it like working with Gary Clarke, Jr., who hasn’t acted before? What was it like working with him and the other musicians who aren’t used to acting?

With Gary, we read him and he was a little shy, but it was like, “Oh god, he can act.” He actually listens and does those great things you want people to do when they’re onstage and in the movies. The hardest thing was to get him to be a showy player, because he’s just not a show-off onstage. He does it all with his fingers. In the fifties you had, I think starting with T. Bone Walker who was like a flash dancer before he was a guitar player, this tradition of guys doing acrobatics onstage and being showmen. I needed a little bit of that from Gary.

I really needed the input of those musicians. It was important to me that the music feel live and as much of it be live as possible. With Keb Mo’, I said, “I want you to go and write your character’s arrangement of ‘Stagger Lee.’” He’s kind of a student of the blues and he came in with a guitar that he bought and said, “Well, Possum only plays in G, so here it is.” And it was great. It sounded exactly like what those guys would have played on a street corner.

|

|

|

We had a luthier named Ted Crocker build one after we sent him the script. I always felt like Gary Clarke’s character was a guy who was a radio repairman in the army and probably read an article in Popular Electronics about what Les Paul was up to.

I wanted something that would really play and so Ted made two identical [guitars]. One had a radio hook-up in the back for when Gary goes out in front of the club and the other for the club doesn’t have the hook-up. It’s a single coil, so it doesn’t have the humbucker.

I wanted the sound of those early guitars. If you listen to T-Bone Walker’s stuff, it’s great, but it’s a little thinner than what came only a few years later when they got the other coil. Where did you get the idea for this film?

It all started with the rock n’ roll legend of Guitar Slim. I think his real name was Eddie Jones, and he was known in New Orleans in the early fifties. He was one of the guys who put that long extension chord on his guitar and in New Orleans where there are a lot of clubs close together, would go into the street and play in the doorway of the other clubs to get everybody in his club. He was also known to miss a gig. I think Earl King was the most famous of them who spent years going out as Guitar Slim. Somebody would pretend to be somebody else, but as long as you could play, the audience didn’t care. There were no rock videos, no album covers, no TV; it was just a name on the jukebox. The celebrity was a lot less important.

|

|

|

Yeah, we did “Born in the USA,” “Glory Days” and “I’m on Fire” for Bruce. The jobs were the only times I’ve ever really worked for hire. It was his story that I was telling, and he had a lot of good ideas for what the visuals would be. If you were going to choose a job that has anything to do with the music business, those were really good jobs.

In the past few issues of our magazine, we’ve touched on rock music entering the church. Discuss the presence of God and the idea of morality, which is very strong in this film, especially in relation to the music.

This was very controversial at the time. I tried to track down what would have been on a jukebox in 1950 in the Deep South and I came across this playlist. One of the people featured was Sister Rosetta Tharp, who played a hell of an electric guitar, but was a gospel singer. Johnny Cash, Bonnie Raitt and other guitarists mention her as an influence on their playing. We shot in Georgiana, Alabama, where Hank Williams grew up. He was famous for playing honky tonks at night and then passing out and being driven to the church he would sing in the next morning. He ended up writing some really seminal gospel songs, and he was a wild guy; same with the Louvin Brothers. Some of them are able to make a living doing just that stuff, and others finally just say, “If I’m going make a living as a musician, I’m going to start singing secular stuff too.”

Where do you think music is heading in a strong technological era?

The thing that record labels don’t like is that it’s heading in every direction at the same time and people aren’t listening to the same thing. So they don’t know how to make money on it. For the musicians, for the fun of playing, it’s a great time, because there are so many things to play and the access to great players is so great. I think for professional musicians, it’s kind of a scary time. Unless you can go out there and tour, the idea of just selling albums is gone. But you can put albums out there as a sample and then you can tour. If you’re tired of the road, it’s a really tough time.

For more information about the film, including a plot synopsis, theater locations, cast bios and interviews, visit honeydripper-movie.com.