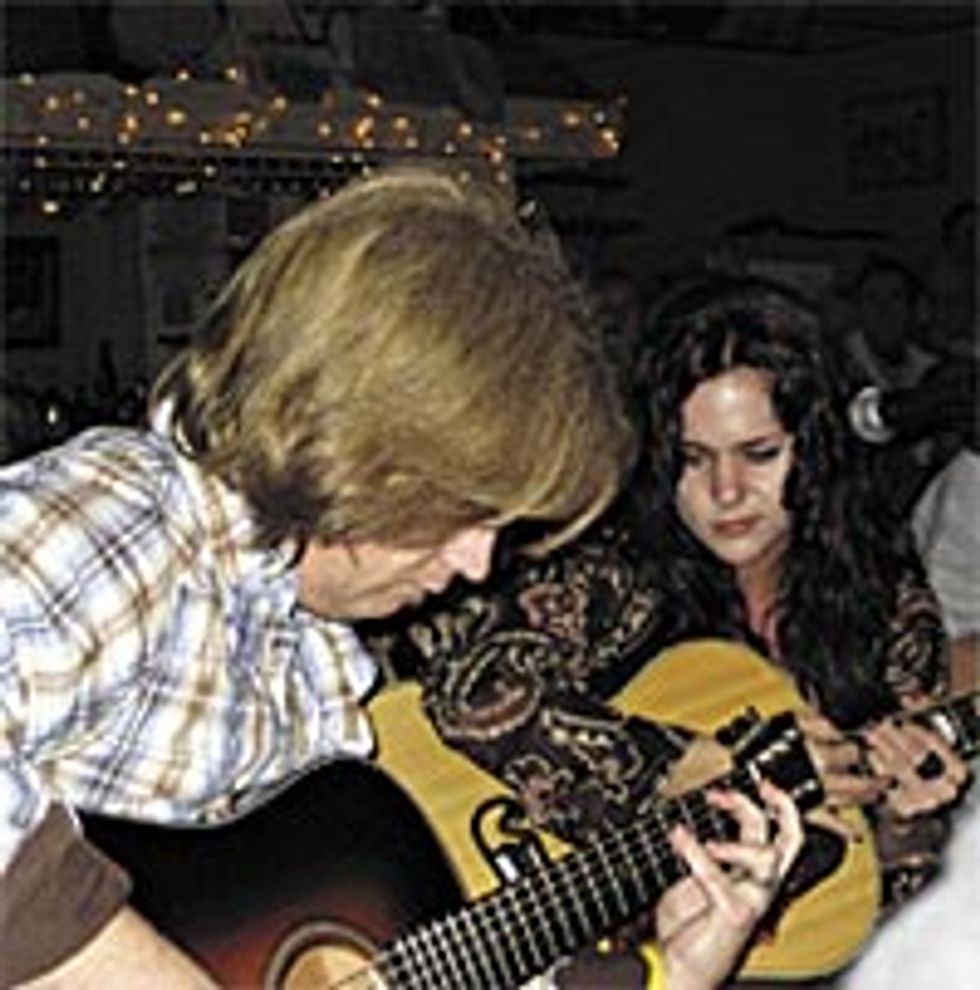

Greg has been able to hone his chops in a variety of situations, allowing him to develop the Zen-like ability to place the right note in exactly the right space, playing for the song rather than for attention

| |

|

When did you decide to play guitar?

When did you decide to play guitar? I started when I was 13, during the summer break between seventh and eighth grade. I loved Elton John and the Who, a lot of great, classic ‘70s rock. I was starting to write lyrics because I wanted to be involved in the songwriting process, but I realized I was a horrible singer and lyricist, so I started playing guitar. The first day was ten hours, the next day was eight hours, then my fingers hurt, so I only played four hours the third day.

Playing until the skin came off of your fingers?

Yeah, the classic story; I had a really horrible old acoustic that my parents bought for me at the PX for something like ten dollars. It had a small little body and really high action. It wasn’t a Harmony, but it was something like that. And, you know, I was just persistent; once I latched on to the guitar it was as though a long lost limb was reconnected. I just couldn’t let go. I wouldn’t let go.

Was there a defining moment for you – like seeing the Beatles on the Ed Sullivan show – when you thought, that’s what I want to do?

That moment was literally getting the guitar in my hands. That’s why I never stopped playing. I don’t think I missed a day of playing the guitar for several years, and I played at least three or four hours a day. Even when I was sick and had to stay home, I was playing guitar. Those were my formative years; I would pick up riffs from Lynyrd Skynyrd and Ted Nugent records, sitting there for hours, picking the needle up and dropping it back down on the record a million times, trying to learn the intro to “Sweet Home Alabama.”

I remember cueing up records over and over.

Yeah, and trying to slow them down to 16 rpm, to learn the quicker licks. If you were a kid back then, and you had that kind of relentless nature to keep doing that over and over, you know there was something seriously driving you. Otherwise, it took too much effort!

Moving forward a bit – how did you then make the transition from high school bands and bar bands to studio and soundtrack work?

Moving forward a bit – how did you then make the transition from high school bands and bar bands to studio and soundtrack work? That was a bit of a process. I played in bands in high school in the panhandle of Florida. My parents lived on a farm in a small town called Laurel Hill, and I was playing weekends there. I was in a couple of different bands; one was a straight up, hard-country band, doing Willie Nelson and Merle Haggard tunes, and the other was a rock band, where we could make more money doing Blackfoot, Molly Hatchet and Skynyrd covers.

Would this have been in the late ‘70s?

Yeah, exactly, this was the late 70’s, and it was a great period of time because there were tons of clubs all along the panhandle. I played all over, from Tallahassee to Mobile, Alabama. You know, I was 16, 17, 18 years old, and making great money for back then.

| “...I started playing guitar. The first day was ten hours, the next day was eight hours, then my fingers hurt, so I only played four hours the third day.” |

You were in high school, in a band, and you got paid?

Not only that, I was playing with great older musicians, and that was the critical part for me. I’ve always played with players who were older than me, and much more seasoned. Just through osmosis, when you’re working with players like that – who are just really good – you absorb a lot. You really had to try to not get better in that environment.

So the more experienced players kept you challenged.

You know, just the great evolution resulting from being able to play with those guys. But I ended up wanting to move out of a small town; I thought I needed to go to a music center. I had a friend in San Francisco who convinced me to come out. He called me and said, “Hey, you should move to out here. Let’s put a band together.” So I graduated, loaded up the car that night, and the day after graduation, I left and moved to San Francisco.

Were your parents supportive, or did they want you to go to college or something more secure?

Were your parents supportive, or did they want you to go to college or something more secure? Since day one my parents were incredibly supportive. I think they were relieved, to be honest, that I found something that I was completely consumed by, and also because they knew where I was. I wasn’t out in the street, I wasn’t gone. I was in the back bedroom, with the stereo playing. My dad always used to know when I turned my amps up at home, because the pictures would be crooked in the living room. He’d come home from work and the walls were shaking. [laughs] I just used to blast my Peavey half-stack. I couldn’t afford Marshalls at the time, and Skynyrd was a big influence.

And they used Peaveys.

Yeah, well I used to have a Peavey Mace, just like those guys had on the live album.

Those were brutally loud!

Exactly! [laughs] My parents were incredible. They always said if I wanted to go to college, they would support it. Of course, they were for that, but honestly, I was almost willing to drop out of school. I wanted to play guitar so bad, to be in school felt like a hindrance. But they laid down the law, and said, “Look, you have to finish high school.” So, as soon as I got the diploma, and satisfied their needs, I was out the door.

What was it like for you in the Bay Area?

I ended up doing the same thing I had done at home; slugging it out in that scene, just trying to get my foot in the door – like meeting people in music stores. I eventually got a job at a local music store in San Rafael, called Bananas at Large.

| “Hey, here’s my guitar playing. If you happen to know anybody who would need this type of coleslaw, please tell them I make this kind of coleslaw.” |

Right across the Golden Gate from San Francisco, right? That’s a great little store.

Yeah, it was a great store because all of thelocal musicians would come in. Remember, San Francisco was very fertile ground in the ‘60s and ‘70s, and I moved there in ‘81, so all of these local guys – Carlos Santana, the guys from Huey Lewis’ band, Neal Schon – would come in. I had a cassette of some songs I had done for another project, and I would hand it out like candy to musicians who came in. And when I handed it out, I would tell them, “Hey, here’s my guitar playing. If you happen to know anybody who would need this type of coleslaw, please tell them I make this kind of coleslaw.”

Did anybody bite?

Did anybody bite? What happened was this guy named Cory Lerios, who was the keyboard player in Pablo Cruise, called me, literally a few hours after I handed him my tape, and said, “Hey, I really like your guitar playing. Do you want to come out and play on some songs I’m writing?” And I said, “Yeah, absolutely! When do you want to do it, sometime next week?” And he was like, “No, how about tonight?”

I went out to his house later that night, around ten o’clock. Cory was very successful with Pablo Cruise back in the ‘70s, so it was a great opportunity for me to work with a really talented player who was not only a great songwriter, but also a great producer and knew the ropes of the music industry inside and out. So, I ended up playing on a lot of demos for him, and not long after that, he got a TV show called Max Headroom.

Yeah, I remember that.

Cory pulled me in on that. He was like, “Hey, I’m going to have you play guitar on this,” because it was kind of a dark, futuristic show, and at that time using guitar sound effects, like dive-bombs, harmonics and low, groan-y notes where you would hold the whammy bar down and do these weird sounds, really worked for this type of soundtrack. And that completely hooked me into wanting to do more session work.

Also, it made me realize, when you’re working with film or TV in particular, that you might only do a ten second cue; you’re not always writing three or four minute songs. I saw that there are a lot of song ideas that you might have that don’t necessarily fit a normal pop-song format, but that could be utilized in other contexts, such as supportive music in cinematic environments.

So that’s how you ended up in San Francisco. Since then, you’ve been all over the place; L.A., Hawaii, San Francisco, Austin for a period of time, and now you’re in Nashville. How did you end up there?

That kind of comes full circle. Growing up in Virginia, before we lived in Florida, I had always heard about Nashville. I had friends who were doing country, and I eventually played country music in high school. I was always kind of coming from an edgier, rock approach, but I always liked country and bluegrass. I still do, I love bluegrass.

I had initially thought about moving to Nashville after high school, but because my friend was in San Francisco, it made more sense; I had at least one couch to crash on. If my friend had moved to Nashville, I would have moved to Nashville. When I was in high school, anything seemed like a bigger world to me.

When I ended up in L.A. in the ‘80s, heavy metal and hair bands were popular, and I was still playing a Telecaster. I rarely used a whammy bar; I kind of resisted while everybody else was using them. Being in L.A. at that time and playing a Tele, I felt like Opie from the Andy Griffith Show. I always felt a little out of step, and I wanted to get back to a song-oriented town; a more organic, roots-music type of scene.

When I ended up in L.A. in the ‘80s, heavy metal and hair bands were popular, and I was still playing a Telecaster. I rarely used a whammy bar; I kind of resisted while everybody else was using them. Being in L.A. at that time and playing a Tele, I felt like Opie from the Andy Griffith Show. I always felt a little out of step, and I wanted to get back to a song-oriented town; a more organic, roots-music type of scene. Then, after living in Austin for ten months, I realized that the Southern experience was something I really wanted to get back into, where things were a bit slower, in a good way. People were more relaxed; there were fewer mice fighting over just the right amount of cheese, so the mice were friendlier. I realized that just made me play better, and it enabled me able to dig into my instrument even deeper because I’m less distracted by life around me.

A place that’s a little more nurturing?

Yes. There’s a tremendous amount of opportunity in a lot of other cities, and I feel fortunate that I’ve been able to live in some of them, and gained the great cultural experiences and all of the other wonderful things that go along with living in a big melting pot of millions of people. But, at this point, I really wanted to come back to where things were lush and green and pretty, and the level of musicianship in Nashville, I think, per square inch, is much higher than I’ve experienced in any other music center.

So it’s like Paris was for jazz in the ‘20s: a scene with everyone at the top of their game.

You know, my joke here is the bagboy at Krogers asks you, “Paper, plastic, or should I melt your face off with some Tele licks?”

Exactly. [laughs]

It’s true. It’s the people who are the best of the small towns, not just across the U.S., but all across the world. I’ve met some amazing international musicians here, basically the best of their respective small towns. People used to tell me, “Hey, you should move to Nashville.” And that’s what happens; these players who are the best of their local areas come here and then they get elevated themselves because they’re all coming here, pushing each other to excel on their instruments. There is a monstrous amount talent in this town – not just musicians, but writers, engineers, producers – the whole infrastructure of the music industry has unbelievable talent.

| You know, my joke here is the bagboy at Krogers asks you...“Paper, plastic, or should I melt your face off with some Tele licks?” |

That leads right into the next question: everyone’s heard of the local hot picker who goes to Nashville, and comes back six months later and signs up for computer programming classes. How has Nashville been treating you?

That leads right into the next question: everyone’s heard of the local hot picker who goes to Nashville, and comes back six months later and signs up for computer programming classes. How has Nashville been treating you? You know, there have been some nights where I’ve been, like, “What am I doing here?” When you go see some of these pickers here, I mean, it’s monstrous. But the difference is if you really have it in your heart, if you have absolute desire and conviction to the art form, then you’re not easily swayed – you’re actually inspired by that level of musicianship, you know? So, on the one hand, I might get terrified briefly, but on the other hand I’m going, “Oh my God, this is what I want to be around!” I want to be elevated. This town can crush people who don’t want that.

I don’t look at music or guitar playing as a competitive sport. No matter how great somebody else plays, you have to recognize they can’t do what you do as well as you do it – hopefully. [laughs]

The trick is finding your voice on the instrument, whatever it is, and figuring out a way to maximize it so hopefully you can make a living with it. I’m certainly not a rodeo, ring-of-fire guitar player – like Brent Mason, Redd Volkaert or Ray Flacke, or even like the new guys here, like Johnny Hiland and Guthrie Trapp. Those are the terrifying players and they’re incredible. I’m much more of an eclectic type player and my approach is more textural – that’s not to say that those guys don’t do that or can’t do that, I’m just recognizing where my talents are best maximized.

That’s great because your playing is really organic and rootsy; it doesn’t ever sound like “name the riff” – it never sounds derivative at all. You seem to adjust from one type – or one style – of music to another fairly easily, which leads to kind of an odd question: is there anything you don’t like to play?

That’s an interesting question. You know, there are lots of things that I can’t play, that I just don’t have an awareness of. For example, jazz. I got as far as getting into fusion, like Al DiMeola, maybe the Dregs, which are not quite jazz, but they were a mixture of almost classical and chicken-pickin’. I can’t sit down and share even several measures of any jazz standards or anything. But having said that, I think if I really loved jazz music, more contemporary jazz, then I probably would have tried harder to play it. But I don’t play classical, you know? I don’t do anything in those sorts of environments. That’s not to say I don’t love to listen to it, for example, Grant Greene, Wes Montgomery and Kenny Burrell, or old B3 trios, like Jimmy McGriff, Jack McDuff and Jimmy Smith. Any of the playing from the mid-‘60s up to the early ‘70s soul-jazz era.

I don’t think I’m so much genre-specific; I’m really song-centric. I like to play really good, well-written songs – and that’s a big part of moving to Nashville; wanting to play with great, nice people – hopefully – and then playing within the context of a great song.

What kinds of jobs have you been doing lately: recording, live, soundtracks, or a little bit of everything?

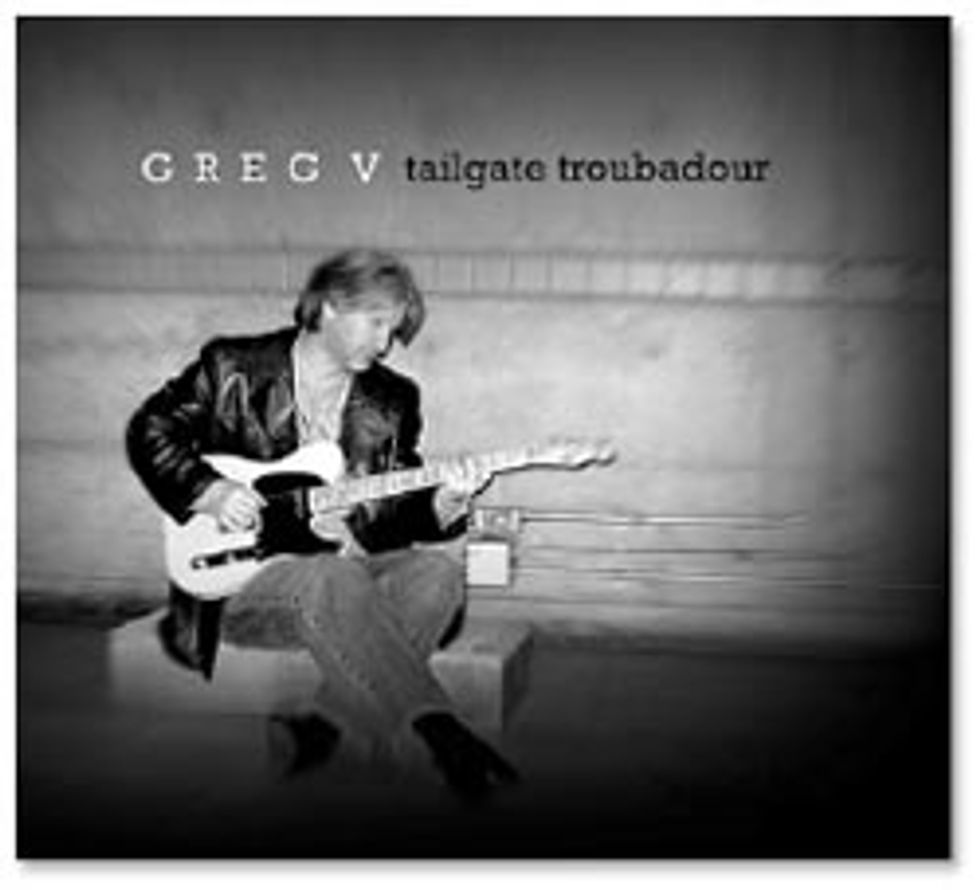

Not so much any soundtrack work. I haven’t been exposed to that here so far. I think those jobs might be more Los Angeles or New York based since so much of the film industry is based in those areas. I’ve been doing more live playing, and session work as well, and a big help for me has been a couple of Nashville A-list musicians here – Kenny Greenberg and Tom Bukovac. They are two of the top tier guitar players here. I put out a solo record Tailgate Troubadour a couple years ago that they were kind enough to give me some feedback on, and they both had called me and said, “Hey, you should move to Nashville.” They were really a turning point for me being able to move here and to be able to meet people and quickly start to get opportunities and gigs. Through Kenny and Tom both, I ended up doing several weeks with Wynonna Judd within a couple of months of arriving here, which was fantastic. That’s kind of a freak opportunity that can sometimes take years and years to get.

| “The trick is finding your voice on the instrument, whatever it is, and figuring out a way to maximize it so hopefully you can make a living with it.” |

Definitely.

Definitely. And I’m incredibly grateful; I don’t take it as, “Oh that’s normal, that’s how it works.” I’ve been very fortunate that these guys have taken an interest in me and have been very supportive. They’ve become great friends. Tom Bukovac got me to play on a bonus track for the new Keith Urban record, and I’d just been here a month-and-ahalf. I was able to play on a Keith Urban session with Dan Huff and Bukovac – all the A-list guys playing – and it was a surreal moment.

What was your first Nashville session like? Were you freaking out, or was that it?

That was it! That was my first Nashville session.

Wow! You don’t mess around.

Honestly, it was daunting. I mean, you move to Nashville, and the move is traumatic enough, just as you get older, you know? You have a wife involved, and buying a home; it’s not as easy as when I was 18 years old moving to San Francisco.

But then to be walking into the studio and you’re seeing these musicians who are like Mothra and Godzilla and Ultra Man, you know? These unbelievable players, top of their game – the highest caliber musicians in the world, and they’re saying, “Hey, Greg, we need you to play acoustic guitar on this. You and Dan are going to play the chunky rhythm part like one big guitar.” It was pretty surreal. One of the most difficult things, and I’m still learning to adjust to it, is the Nashville Number System [see sidebar for more about this notation system].

When we talked before, you had mentioned doing some live playing. How does the live scene in Nashville currently compare to some of the other places you’ve lived, like L.A. and Austin?

Well, it’s kind of sad, actually. There’s a tremendous amount of musical talent here, and there’s a reasonable amount of live venues, but unfortunately, musicians are not getting the support from people to come out and see them play, or from club owners being able to pay them a reasonable amount of money. So what happens is a lot of musicians play in Nashville not so much to make money, but to have the emotional release from performing live on stage – especially a lot of the session musicians. They’re doing sessions all day long and they sometimes go by so quickly, and they can be very high-pressure situations. If you’re doing somebody’s record, they might want to get three, four, five songs done in a day, but if you’re doing demo sessions for a publisher, they might be getting ten songs done within a three hour period, and it’s unbelievable.

When you’re in that compressed environment in the studio, sometimes it goes by so quickly that you want to get out and play something where you can just do whatever you want, and that’s where the live gigs come in wonderfully. They give you a chance to just blow off some steam and exist in a looser environment. Having said that, there are many musicians who make a lot more money playing outside of Nashville; they’ll drive to Memphis, Atlanta and so forth because they’re able to make a better living in terms of the live environment.

Don’t get me wrong, there is a lot of live music in Nashville, it’s just that it can be quite difficult unless you’re playing covers, or doing showcases, which happens a lot here, where great musicians will play for artists who are trying to get record deals. You can do quite well with those type of things.

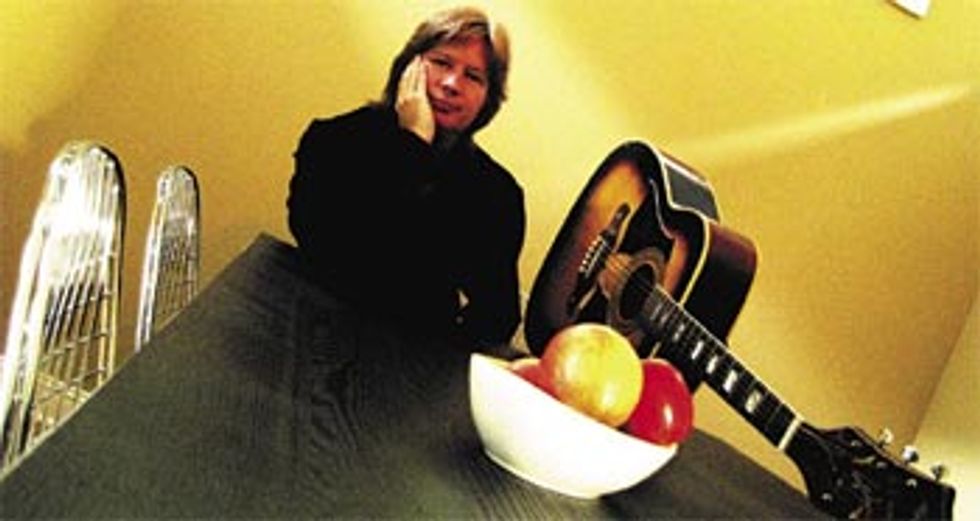

Let’s switch gears a little bit. What kind of gear are you using these days? What are some favorite pieces?

Well, my mainstays go along with roots and classic rock type stuff. I use Fender amps a lot, like a bunch of vintage Fender amps. The Pro Reverb is a great mainstay and Super Reverb and so forth, but there are a couple new amps that I’ve been using that have been absolutely stellar. They’re new amps called Swarts. They’re made by Michael Swart in North Carolina and I’ve got his whole range of amps. He makes a little five watt amp which is not exactly a tweed Champ, but it’s in that realm, and it’s quite loud, actually. It’s great for recording or if I’m playing a very intimate club gig when you’re just playing with an acoustic guitar, and you want to have nice tone without pissing off the lead singer or whatever. I also use Atomic Space Tone, which is about 20-25 watts and a tremendous amp. It’s fantastic for roots-type stuff because it splits the fence between a blackface and a tweed, where it’s got thick mid-range if you want it, and it has a really nice, clear and articulate top-end, too. I love these amps. They’re all hand-wired and they feel very comfortable. Even though they’re new amps, they harken back to the ‘50s; they’re really well-made. A lot of times when you’re using vintage amps you’re dealing with forty-plus-year-old components and the last thing you want to do is kill a session because your amp starts to blow up.

How different is the rig that you take to sessions from the one that you take to showcases or what have you?

How different is the rig that you take to sessions from the one that you take to showcases or what have you? In some regards, it’s quite similar; it all depends. On the live gig I have a multitude of amps, depending upon the size venue I’m playing. For example, I don’t want to take a bazooka, like a Super Reverb, if I only needed a butter knife, like a little five watter. I try to bring the right size knife to the right size knife fight. I don’t really like to have a big amp turned down, I’d much rather have a small amp turned up into the “sweet spot” where the power tubes and the circuitry really start to work.

I like to use a spider web as an analogy; I like my whole rig to be incredibly lively, like a spider web. If you touch a spider web very lightly, it’s very sensitive to nuance and detail, but if you hit it hard it flexes and springs back to life. I like to have my rig at that point. Sometimes you’ve got to turn an amp up to where you not only get the power tubes cookin’, but where you get the speakers starting to jump around, too, making it important to have the right wattage for the room. In the studio you’re often isolated from your amps so volume is not as much of an issue, it becomes more a matter of the voicing of the amp to what you’re trying to achieve. That’s where having a huge amount of pedals is real beneficial because a lot of times I’ll use kind of a loud tube amp turned up as a platform for different pedals to create different sounds.

Are there any pedals out there that you’re really excited about?

Oh yeah! Last year a friend of mine gave me a Timmy pedal and it’s fantastic. It can be a clean boost, a mild overdrive, and the beauty of this pedal is – everybody uses the word “transparent” – but it has the potential to be absolutely transparent. And it’s small, which is great because space is always at a premium on a pedal board. It’s just unbelievably versatile. It’s made by a guy, Paul C.,v here – ironically enough – in Nashville. It works great with tweed as well as blackface amps, and it’s very organic and very amp-like. When you turn it up, if you hit your guitar hard, it pops and it really crunches; if you play softer, then it starts to clean up very nicely – almost like The Who – Live at Leeds or something.

Sweet. Are you still mostly using Teles?

Well, Teles are a big part of it, yes. I have Custom Shop Nocasters, which are kind of a mainstay for me. I mean, they are my favorite guitars – Teles – to play, hands down, but, I do have a couple Gibson historic guitars. I have an historic ‘59 Les Paul and an historic ‘61 SG – because again, in particular Tom Bukovac, who I mentioned earlier, has kind of been the antithesis of the “Nashville sound” for years. He’ll use tons of old Gibsons through Bogner and Diezel amps. He’s on all the major hits and yet he’s using a much more rock-oriented sound. Of course, if you put a Tele in his hands, he’ll just rattle off some of the most unbelievable machine-gun chicken pickin’ as well – he’s one of those guys who can literally play anything. When he’s in the room, I sit on my hands. [laughs]

Greg, thanks for taking the time to chat with us. I really appreciate it.

Yeah, James, man, thank you; I’m grateful for the opportunity.

| Greg describes the Nashville Number System |

| “I’ve never approached music other than a Blues tune as I – IV – V. If somebody called out a tune anywhere else I’ve lived, and it was in the key of C, they would say it was C, A-minor, D-minor, F, G. Here they’ll say it’s a I, VI minor, II minor, IV, V. My brain has a little filter now where I relate to the chords in their numerical reference. It’s a phenomenal way to communicate music because when you change keys the number reference never changes. If they call out the song in D, the I, VI minor, II minor, IV, V don’t change, just the reference chord, so it’s really efficient. “What is difficult is musicians here read the Nashville Number System like reading a cereal box. I’ve been to sessions with Tom Bukovac when he’s leader on the session. He’ll have a pencil and a piece of paper. They play the song down that they’re going to cut, and he starts writing the changes down, and he doesn’t have a guitar anywhere near him. These aren’t just I – IV – V progressions; some of them are very complex, with quite a few chord changes. “They then send that to the assistant, who makes copies, and hands them around the room. The musicians go out there, and first take is like you see them chiseling rocks off of a marble slab, and by the second or third take you’re like, “Oh, my God, they’re recording!” Although the first takes are usually brilliant, the second and third takes are usually where the band solidifies. So you had heard something just a few moments earlier that nobody had heard before, and by the second or third take it sounds like the best band in the world has cut the song like it can never be cut again.” |

Greg V’s Gearbox

|

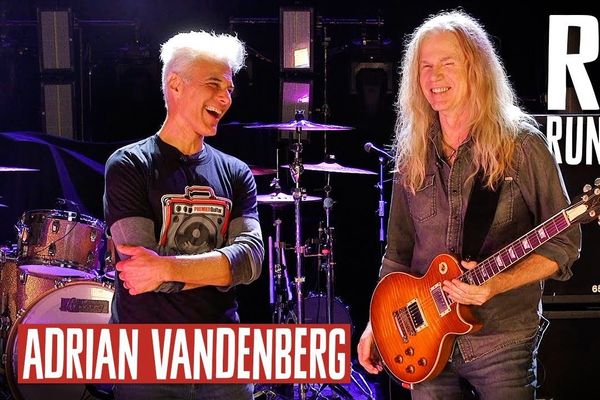

Greg V.

gregv.us