Black Mesa''s Logicaster shows off luthier Clint Dougherty''s TorsionLogic neck mount design

Nearly since they first left the Fender factory in Fullerton, California, the Stratocaster and Telecaster have inspired luthiers and machinists to attempt to recreate and improve on what made them two of the most revered instruments in existence. The philosophies of these luthiers range from a purist, nothing-but-the-original-spec approach to swearing by mysterious components and tonewoods whose characteristics are so unquantifiably hallowed that you’d think they came from Tolkien’s Forest of Fangorn. Black Mesa Guitars luthier Clint Dougherty falls somewhere in the middle. However, he says he bases all his tweaks and innovations on logic rather than any mystical tone juju.

The son of a physicist who also played classical guitar, Dougherty always enjoyed both music and science. As a musician, his first love was drums, but he later fooled around with bass and then ended up bonding with the guitar last. He’s been building Black Mesa Signature models—which feature a range of customizable options and wood choices on unique body styles—for more than 10 years. But perhaps his most distinguishing work is the player-friendly, science-based adjustments he came up with to try to bring Leo Fender’s ideas into the 21st century.

“I wanted to find new and better ways to build things within the parameters and restraints imposed by the physics of lightweight, hand-held tension structures, rather than simply replicating familiar instruments,” Dougherty says. And then his wife ignited an “Aha!” moment for him that inspired implementation of his TorsionLogic neck—a proprietary, rear-mounted bolt-on design that provides extreme access to upper frets—on familiar body styles such as Stratocasters and Telecasters.

“After listening to me rant about how so many guitarists never look beyond the Strat, she said, ‘Well, why not build a Strat with your neck system?’” Dougherty recalls. “So I realized it might be attractive to players who love their classic styles to have a familiar look and feeling with two full octaves and improved upper-fret access. It always seemed redundant to me to expend a huge amount of my time and energy just going over ground that has been so thoroughly plowed over the years.”

Since then, Dougherty has been building batches of Logicaster TL-T and TL-S models with the TorsionLogic neck-mounting system, all while maintaining production on Black Mesa Signatures that also use the TorsionLogic system.

TorsionLogic

Dougherty developed the TorsionLogic in

2005 because he’s always been attracted

to the idea of providing as much range and

upper-fret access as possible. He initially dabbled

with neck-through designs but “didn’t

like the bright, sometimes brittle tone and

the inability to dismount the neck for repairs.”

So he moved on to set necks, but found

that “those styles have some of those same

issues plus some others, like the loss of

strength when routing pickup cavities.”

Dougherty developed the TorsionLogic in

2005 because he’s always been attracted

to the idea of providing as much range and

upper-fret access as possible. He initially dabbled

with neck-through designs but “didn’t

like the bright, sometimes brittle tone and

the inability to dismount the neck for repairs.”

So he moved on to set necks, but found

that “those styles have some of those same

issues plus some others, like the loss of

strength when routing pickup cavities.”After reading a 2007 American Lutherie magazine article with substantial scientific evidence that bolt-on designs “offer superior resonance and sustain around the fundamental and successive harmonics,” Dougherty’s idea was solidified by scientific evidence. He explains the logic behind the system as, “If you move the neck pocket to the back of the body, the neck heel can be made a lot longer, greatly increasing the contact patch between the neck and body without losing any of the neck meat to pickup cavities. Additionally, the torsional load produced by string tension pulls the neck into the body, which further improves the strength of the structure. There is no honking slab of wood sticking out of the body to screw the neck to, so there is plenty of room to sculpt the joint and make the cutaways a lot deeper, as well. It’s really a way to incorporate the best features of all three neck-mount styles—without the disadvantages.”

The Logicaster Body

Standard TL-T models come with a quilted

maple top and sapele body, but the TL-T

shown here has a custom chambered body

that reduced the guitar’s weight to 6 lbs. 14

oz., a more manageable weight that still maintains

good resonance and a solidbody tone.

Standard TL-T models come with a quilted

maple top and sapele body, but the TL-T

shown here has a custom chambered body

that reduced the guitar’s weight to 6 lbs. 14

oz., a more manageable weight that still maintains

good resonance and a solidbody tone.

Logicaster Fretboard, Neck, and Headstock

TL-T models generally come with jatobá fretboards, because Dougherty believes jatobá has many of the same tonal characteristics of rosewood and maple, but is easier to get and “sturdy as hell.” This particular model has a bubinga fretboard. Most TL-T models come with hard rock maple necks. He devised an angled, under-side mount headstock that has a beefy volute to provide greater strength to this vulnerable area.

TL Pickups

On standard TL-T models, Dougherty uses various handwound Sheptone pickups. Because of the extended 24-fret neck and deep cutaways, he had to adjust the usual pickup placement on both models. In a short essay on Black Mesa’s website, Dougherty describes his theory behind pickup location as “If you envision a vibrating string as a sine wave, it is easy to see that while a node, that is, a place where there is little or no string excursion, is indeed a precise point, an anti-node can be seen as more of a zone. A pickup located almost anywhere in that anti-nodal zone will be sufficiently excited to produce a usable signal. Naturally, the output will diminish proportionally to the pickup’s distance from the node, but you really have quite a large area in which to locate a pickup, especially at the neck position.”

Of course it all boils down to a very simple question— does it sound good? And Dougherty stands firmly behind the tone of the Logicasters and their alternative pickup positions.

Logicaster Pricing

Black Mesa’s Logicaster base models start at around $1400, which includes a setup of the sapele body, jatobá fretboard, and pickups. You can customize some options on the Logicasters, but Dougherty prefers keeping the models somewhat standard to keep them affordable. For more hands-on buyers, Black Mesa Signature models are completely custom—down to placement of controls. Dougherty currently has a very limited amount of semi-finished and ready-to-play models, but mostly works on a build-to-order format.

blackmesaguitars.com

How to accompany a singer without drowning them out.

William Shakespeare wrote “All the world’s a

stage…and one man in his time plays many

parts.” What does Shakespeare have to do

with guitar, you ask? Not much, really. But

it’s true that, as musicians, we will play many

parts over the course of our careers. I have

had the good fortune of getting to back some

of the biggest names in the business (including

Toby Keith) as a sideman. The task at hand

when backing these giants is to lay down a

rock-solid lead guitar part: I take my solos

where needed, throw some appropriate fills in

between vocal lines, and generally try to stay

out of the singer’s way.

With a band, the bassist generally controls the

root, while a keyboardist or second guitarist

bashes out the chords and other instruments

share in playing fills. In country, there’s normally

a steel guitar and/or fiddle to help fatten

the sound and give the tune the essential

twang factor. With a bigger band, you can get

away with smaller chord inversions, and often

you can play three-note chords (such as root,

third, fifth or third, fifth, root) to make the

band sound big without getting in anyone’s

way. Or you can just lay out and stab at some

of the fills and leads when they come up.

Changing the Rules of Engagement

As a solo artist, the approach is completely different:

When I’m at center stage, it’s my responsibility

to take over the melody and lead the

band—I have to move from playing in the open

spaces to playing the lion’s share of the song.

And all the rules change again if you’re the only

instrumentalist accompanying a vocalist.

I’ve done a good bit of work accompanying

singers with just my acoustic guitar. When I

played with Rodney Atkins, he and I would

do writers in the round, where he would sing

and I played. I’ve done the more intimate

“An Evening With”-type shows backing

Chalee Tennison (who, by the way, is one of

country music’s most gifted vocalists). Again,

she would sing while I captured the essence

of her music al dente. I’ve coupled with

my long-time boss, Toby Keith, to perform

stripped-down versions of his mega hits. And

I’ve backed Mica Roberts on tours where it

was just my guitar and her incredible voice

entertaining sold-out crowds across the UK

and northern Europe.

When you’re performing as a solo accompanist,

you have to make the most extreme adjustment

in your attitude toward the instrument.

The task of creating the groove and setting the

tempo—which normally falls on the drummer—

is now in your hands. You no longer have a

hi-hat to lock into, because you’re creating the

feel of a drummer on guitar. You become the

band. It’s important not only to play the chords,

but to build chord structures that make sense,

sound full, and lead the vocalist—as well as the

audience—through the song, while giving them

a sense of the full arrangement.

We are not all as gifted as guitar virtuoso

Tuck Andress at comping full walking bass

lines while keeping up with fast-moving chord

progressions. But I find it is helpful to pick up

important elements of the bass line, such as

passing tones or walkdowns. It’s one of the

details that helps create that full-band feel.

Get Creative with Dynamics

Dynamics are also extremely important when

you‘re the lone instrumentalist. Well, they’re

always an important part of music, but when

you’re all alone you can’t come down low

enough or dig in deep enough as the song

calls for it. You can do so much with the

arrangements if you just pay attention to how

the whole song affects you as a listener. If the

complete recorded version of a tune comes

way back dynamically on the bridge, you

can lay way out and just lightly strum or play

muted fifths, giving just a hint of the chord

progression on the downbeats. However, if

there’s a prominent string line, for instance,

you can incorporate that into your playing so

the listener gets the full gist of the original

arrangement. All this makes a rather stripped-down

version of a song more interesting.

When a song calls for fingerpicking, I like to

use open tunings where possible to build voicings

based on the full spectrum of the song.

Using the bass notes on the bottom to keep

an unmistakable chord change ever present,

I’ll grab some of the standout lines from

within the song and throw them on top while

keeping the basics of the progression in the

middle for the full trifecta. There have been

times when I’ve even been known to bang

out drumbeats on my guitar to reproduce the

beat between changes. It’s all to bring out the

details that make the song unique. Because,

let’s face it, most songs have similar chord

progressions, and that can get old if you simply

beat out the sequence with little emotion

or vibrancy. Take away the vocals, and the only

thing that gives a song its unique character is

what the musicians do with it.

Which reminds me to leave you with an infamous

story about the immortal Grand Ole

Opry star Grandpa Jones. A Nashville songwriter

told Jones he’d just written a new song.

Jones responded “Oh really? What’s it sung

to the tune of?”

Keep jammin’!

Rich is a highly sought-after Nashville guitarist who has performed with singers ranging from Steven Tyler to Shania Twain. He currently plays lead guitar for Toby Keith, and also works as a spokesperson for the Soles4Souls charity (soles4souls.org). His new album, Cottage City Firehouse, is available at richeckhardt.com and CDBaby.com

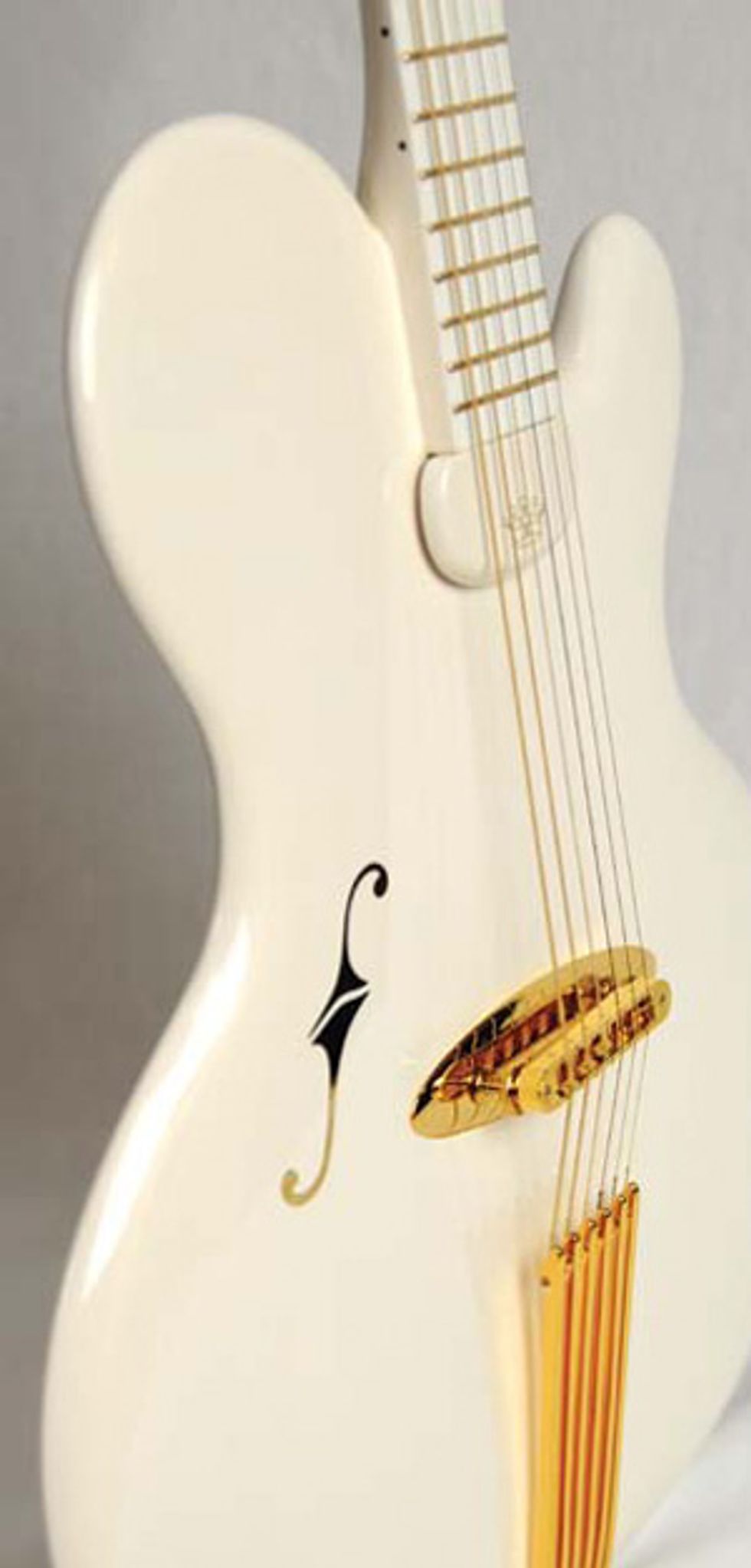

German master bass luthier Jens Ritter''s first electric guitar, the Princess Isabella baritone jazz solidbody, is reviewed.

Click here to see the full-size video. |

|

German luthier Jens Ritter is a trained engineer who got into building guitars and has since attained a fair amount of fame as a custom bass builder. If you have a look at the instruments on his website, you can’t help but be struck by the fact that they have an artistic look and give the impression of being well engineered. Maybe that’s why I was a little unsure what to make of this guitar when it showed up, but I jumped in to see where it took me.

Crowning a Princess

The Princess Isabella got its start when Ritter,

during a trip to New York City, visited Rudy

Pensa at Rudy’s Music shop. Pensa wondered

aloud what sort of jazz guitar Ritter might

come up with, and the wheels started to turn

in Ritter’s mind. When he completed the

design work, he even decided to name the

guitar after a young girl he met on the trip.

The Princess Isabella got its start when Ritter,

during a trip to New York City, visited Rudy

Pensa at Rudy’s Music shop. Pensa wondered

aloud what sort of jazz guitar Ritter might

come up with, and the wheels started to turn

in Ritter’s mind. When he completed the

design work, he even decided to name the

guitar after a young girl he met on the trip.But while the Princess Isabella was built to emulate the sound and feel of an archtop jazz guitar, it certainly doesn’t look that way. We’ll get to the sound shortly, but let’s start with what it is. The most obvious thing about the PI is that it is white from stem to stern. Every bit of wood is finished in a lovely white shade, and while one of my core beliefs is that the only guitar that looks good in white is a Strat, the finish work here is flawless. The trim is all in 24k gold plating, and there is even a faux f-hole rendered in gold. The body is made of very thin and light swamp ash, while the neck is mahogany with a maple fretboard. The striking tailpiece is made of hand-cast spring steel that was gold plated by a jeweler in Ritter’s hometown of Deidesheim. The tuners are gold Gotoh 510s—the best money can buy. The bridge is a Schaller GTM custom, which is much like a Gibson Nashville Tune-o-matic. It sits on a 24k-gold-plated brass foot that floats on the guitar’s top over a hollow internal chamber that is meant to enhance attack.

The pickup, which fits the guitar’s vibe perfectly, is made to Ritter’s specs by Häeussel Pickups. It uses rare-earth magnets that are quite powerful, facilitating a very thin, good-looking design. The guitar also has a very large 24k-gold-plated backplate that covers the pickup wire channel as well as the hollow space under the bridge.

A Solidbody Jazz Guitar?

This brings us to the fact

that this is, in fact, a solidbody

guitar. And when I tell you it’s

thin, I mean thin—about an inch

thick. So if you are used to a hollow

body and resting your arm, forget

it. It’s really too thin for comfortable

arm resting. But, the

body shape is wonderfully

comfortable and feels

great when you’re

standing. It also

rests very nicely in

your lap. Further,

the body is amazingly

resonant

and vibrates like

a living thing in

your hands. Ritter

takes particular pride

in jazz-great George

Benson’s amazed reaction

to this being a solidbody, and

rightly so. And the playability of the Princess Isabella is everything you could

want from a $10,000 guitar. It plays effortlessly.

This brings us to the fact

that this is, in fact, a solidbody

guitar. And when I tell you it’s

thin, I mean thin—about an inch

thick. So if you are used to a hollow

body and resting your arm, forget

it. It’s really too thin for comfortable

arm resting. But, the

body shape is wonderfully

comfortable and feels

great when you’re

standing. It also

rests very nicely in

your lap. Further,

the body is amazingly

resonant

and vibrates like

a living thing in

your hands. Ritter

takes particular pride

in jazz-great George

Benson’s amazed reaction

to this being a solidbody, and

rightly so. And the playability of the Princess Isabella is everything you could

want from a $10,000 guitar. It plays effortlessly.Playability and Tones

The PI has a scale length of 28", which makes it a baritone. However, it arrived strung for standard tuning. After spending a lot of time with the guitar I can tell you that it plays so well that I didn’t notice the longer scale length at first. If you have big hands, this will not be a problem—and it may be what you’ve wanted all your life. If you have small hands, you’ll have to try it and see how it works for you.

Tone-wise, the PI has a really lovely sound. Overall, it has a very organic, acoustic quality. Ritter chose to build it with no onboard controls so the sound would be as pure as possible. So, between the fine-quality wood, great pickup, and excellent playability, what you have seems to be quite true to what Ritter was going for. The PI sounds simply wonderful for solo guitar. It has perhaps more sustain than an archtop, but it retains a seemingly delayed attack very much like a traditional jazz guitar. This attack is the result of two key things (among others): the spring-steel tailpiece and the hollow area under the bridge. I asked Ritter why he didn’t go for a wooden bridge if he wanted arch-top-type response. He told me he tried quite a few different bridges of various materials and got the best response from the metal bridge that is now part of the design. And it makes sense when you consider that banjo mutes work by sticking a lump of brass to the bridge. I should also note how much I like the sound of brass saddles on a Telecaster. So, however it works, it does work.

As a long-scale standard guitar, the PI is quite successful. However, I was curious how the guitar would respond with the bigger strings and B-to-B tuning. The answer is that the very resonant swamp ash body really rattles your teeth—in the good way. It’s good to be reminded that one of the things about luthier- built guitars is the care they take in wood selection, and it really shows in the PI.

The Final Mojo

I’m not sure how many jazz guitarists are searching for a baritone, let alone a bright white-and-gold solidbody. Nevertheless, the Princess Isabella is the result of a great deal of research by a very thoughtful man, and it shows in spades. You already know from looking at the pictures if you like it’s look or not. But nobody will find flaw with the quality craftsmanship and design work. Further, though our review guitar was numbered 3 out of 50, Ritter still considers it a prototype, and he has already made refinements in the design of subsequent PIs—including getting rid of the ample neck volute. (He did so by impregnating the area between the peghead and neck with a resin that makes it stronger.) The guy is always thinking about his next move.

Needless to say, the PI is quite an unusual guitar with its long scale, unique look, lack of onboard controls, and steep price. But, get over it. It’s a big world and it is made richer by artists that think differently. As for the price, I know guitar players are, let’s face it, cheap. But all I can tell you is that there are tons of cheap guitars available, and you often get what you pay for. When you want the upper-echelon quality of a handmade custom instrument, you have to save your pennies and get ready to pay. Sometimes it also helps to remind yourself that, price-wise, guitars are still at the low end of stringed instruments.

As for Ritter, keep in mind that he’s a custom builder, and as such he’s open to what you, the customer, want. So if you want a short-scale Isabella made with exotic, beautiful woods and 10 knobs, he’ll build it for you. And I am betting it will be extraordinary.

Buy if...

you’d like a fine, world-class instrument that looks like nothing else.

Skip if...

you are old-school and broke.

Rating...

MSRP $10,000 - Jens Ritter Instruments - ritter-instruments.com |