The new hand-wired EC Tremolux delivers greater-than-the-sum-of-its-parts clout with a super hip tremolo circuit and power attenuation capabilities.

There’s nothing more blues than a Fender Tweed. From a visual standpoint, a Tweed Deluxe, Bassman, and Twin are probably the most essential and ubiquitous electric blues accessories. Looks don’t count for much if you ain’t got the sound though, and Tweeds shape the sonic signature of everything from the sting of Muddy Waters’ Chess sides to Slim Harpo’s throbbing and shuffling Excello slabs.

Such truths are not lost on a blues scholar like Eric Clapton. And given his storied infatuation with electric blues in its most authentic forms it’s surprising that we didn’t see a Fender Tweed with EC’s initials on it sooner. But if you’re a fan of compressed, exploding, South Michigan Avenue tones it may well have been worth the wait, because the new hand-wired EC Tremolux delivers the greater-than-the-sum-of-its-parts clout with a super hip tremolo circuit and power attenuation capabilities that make it handy beyond blasting the front row at your local juke joint.

Dressed to Kill

The EC Tremolux is based on Fender’s first generation Tremolux from the mid ’50s, which for all practical purposes, is the legendary 5E3 Tweed Deluxe with tremolo. That means it’s rated at right around 12 watts (a figure that never fails to surprise), which is churned up through three 12AX7 preamp tubes, a pair of 6V6GTs in the power section, and a 5Y3GT rectifier tube.

The Tremolux is beautifully built—on par with anything you’d see from a boutique builder. The pine cabinet, which also helps makes the Tremolux quite light, looks clean and immaculate, and the lacquered Tweed covering is flawless at the seams. Even the most nuts-and-bolts parts of the amp look cool—right down to the Celestion G12-65.

The control panel looks as simple as they come, though the simplicity belies the amp’s versatility. An Output switch just adjacent to the light jewel attenuates the power by about half. Next to the Output switch you’ll find the Speed control for the Tremolo. It’s the only control for the Tremolo, which might be a bummer for players looking for a deep, chopping trem. But those that dig a cool throb to put on top of their blues shuffles will probably enjoy the simplicity. Apart from the Tone and Volume knobs, there are high- and low-gain inputs. It’s a beautifully simple control set that beckons you to fire up and go.

Down and Dirty

Anyone who has ever played a little Tweed like a Deluxe or Tremolux can tell you that a simple circuit and control set don’t necessarily translate to crystalinity you often associate with Fenders—even small ones like Blackface and Silverface champs. Instead the Tremolux is full of color and character, even at low volumes. If you need pure bell-like chime and jangle for, say, your Telecaster’s bridge pickup, you might end up a little frustrated with how much color the Tremolux adds to an otherwise clean tone. But if you’re constantly looking for ways to pepper your jangle with a little attitude, a Stratocaster or Telecaster with amp volume between 3 and 5 and generous application of high end via the Tone knob gives you a sweet, butt-kicking Tom Petty-style rhythm tone. You may not be able to hear too much of it over a raging rhythm section, but it’s a very cool recording texture.

To compete with a loud band, you’ll have give the Tremolux some gas. And when you do, the little Tweed gets mean. Needless to say, the Tremolux is not a high gain monster, so when you do crank it the grit and overdrive are accompanied by a heavy amp compression that’s a signature of Fender Tweeds, but can sound odd to the uninitiated, or those inclined to believe that a cranked Tweed is all that stands between them and their inner raging Neil Young. With a Stratocaster in any one of the three positions from the bridge to middle pickup, the Tremolux takes on a honky, saxophone-like hue on chords and Keith Richards/Chuck Berry two-string stops played between the first and ninth frets. Single note solos up above the ninth fret have sweet and biting character that retains some of that cool sax-like color. And true to form, working through a Jimmy Reed shuffle that’s punctuated with leads up at the 12th fret is a slice of blues heaven—husky, bass-rich, tight, and singing when you need it.

In general, Les Pauls sound everything from bossy to muddy. The compressed character of the amp can makes it hard to summon the whole breadth of a humbucker’s harmonic richness. Getting a really slicing tone from a Les Paul means cranking the tone, putting a little kick behind your pick attack, and keeping the neck pickup out of the mix. It’s a glorious tone, and a combination of dynamic pickwork and volume knob control will help you get the most out of it. In general, though, the Tremolux seems to have the most range with a Telecaster or Stratocaster or mini humbucker-equipped Gibson Firebird out front. And the combination of twang and harmonic content from the Telecaster in particular, is an especially good fit. Muddy would be pleased.

The Verdict

When the Tremolux is in its sweet spot, you’ll never want to leave—especially if you’re a blues head with electric South Side inclinations. A good Telecaster or mini humbucker-equipped axe will make this amp sound liveliest, and you can expand the vocabulary of those combinations with pick dynamics and deft use of your guitar volume knob. Humbuckers are a less-than-perfect match for the super-compressed upper half of the amp’s power range, though they’ll record well at lower levels

The $1,999 price tag may give pause to some, though it falls in line with many hand-wired Deluxe clones that don’t have the Tremolux’s very cool Tremolo or power attenuation capabilities. It’s a lot to pay for an amp that doesn’t have miles of headroom and isn’t exactly multi-dimensional. But what the Tremolux does, it does beautifully. And in the studio, where you can roll back the volume, give it a little more room to move, and even throw on a little fuzz, the Tremolux can be a very capable little beast. At the end of the day, though, the Tremolux belongs in a roadhouse cranking away over a drums and bass trio blasting dirty blues and belting rowdy Telecaster licks. And if you have the coin to spare, it might be the best juke joint wingman you ever had.

Buy if...

Muddy Waters is your man!Skip if...

you’re looking for something a little cleaner for your janglepop masterpiece.Rating...

To give yourself—and your mix engineer—the greatest flexibility in the final stages of production, consider splitting your signal before it hits the delay and capturing two guitar tracks, one clean and one effected.

This screenshot from a Pro Tools session shows a mono Tele track (top waveform)

above a printed stereo delay track.

As a mixer, I receive many different kinds of tracks in various states of readiness. Some sessions arrive with tracks that are perfectly printed, trimmed, and labeled. Others can be a mess, with extra-hot levels and track names like “Audio 1” or “Extra track.” Though irksome, many of these problems can be fixed later on. But some things—including guitar parts printed with integral delay effects—cannot. You simply can’t peel off or alter the delay or echo if it turns out it doesn’t sound like what you’d hoped for when you tracked it.

Of course, it’s understandable that layers of echo may be an essential part of your sound. The Edge and Albert Lee are two players who often build parts around precisely timed delay. But most of the guitar tracks I receive do not need to have delay applied during the recording process. However, if you must have delay on the track to get the right vibe, here are a few things to consider when laying down your initial parts.

To give yourself—and your mix engineer—the greatest flexibility in the final stages of production, consider splitting your signal before it hits the delay and capturing two guitar tracks, one clean and one effected. This approach works whether you’re recording direct or mic’ing an amp, or doing both simultaneously.

It’s true, splitting your signal and recording dual tracks takes more effort than simply slapping a mic on your amp and capturing the sound you get playing through your pedalboard. But without a doubt, taking this dual-track approach can help save a great guitar performance that might otherwise have to be redone if your effects were not tweaked correctly to begin with.

If you’re recording into a digital audio workstation (DAW) such as Pro Tools, Logic, or Cubase and using a delay plugin, simply route the delayed guitar signal to a second, dedicated track. This means your dry guitar goes to one track and your echo effects are captured independently on another. In other words, you’ll generate two tracks for each pass.

For example, if you have a mono guitar track and are sending some of that signal (via an aux bus) to a stereo delay plug-in, you’ll want to “print” or record the output of that delay to its own track.

Sure, you could just run the plug-in as a virtual, unrecorded effect and wait to print it in the mix, but what if your plug-in authorization expires in the middle of the session (for example, if you’re using one with a limited free-trial period)? Or what if you hand off the session files to a mix engineer who doesn’t have that particular plug-in? Or what if the settings don’t come back exactly as you last left them? All of these are real scenarios that have happened to me, and they’re no fun. So it makes sense that, once you’ve gotten a great-sounding delay out of a plug-in, you should print the output to a new audio track.

There it is—done.

But don’t just stop there— make sure you label the track clearly. For example, “Guitar 1 Delay Print” reminds you or informs the mix engineer about what is lurking in that waveform. Also, in the notes section of the track, write down what delay you used, as well as the most important parameters. I’ve even taken screenshots of plug-in settings to save with the relevant session. Just remember to label those, as well.

One advantage of using software plug-in delays (and there are many amazing versions available from various companies) as opposed to a rackmount unit or stompbox, is that you can go back after the session to tweak the delay by changing the settings. If you do that, simply reprint the new settings directly over the old printed track or save a new track called something like “Guitar 1 Delay Print - Version 2.”

While I’m on the subject of printing tracks, many of us also use guitar-amp simulator plugins. As with delay, it’s a good idea to print your amp-simulator tracks. This ensures that any mix engineer who receives your session will have the exact guitar sound you wanted.

I always ask my clients to print any important effects or emulations—particularly for the guitar. This is especially critical when doing cross-platform mixing, such as tracking in Logic and mixing in Pro Tools. When working on the same platform, I also ask them not to delete the original tracks so I can adjust the sounds or alter the EQ if need be. I will also ask for a basic list of plug-ins that they use.

So, next time you’re tracking a guitar part, think about how those effects will translate down the line. When using hardware effects, try to split your amp or guitar signal before it’s processed. And if you’re using a DAW with plugins, print your effect tracks separately. It will save time and money, and make you happier with the end results.

Rich Tozzoli is a

Grammy-nominated

engineer and mixer who

has worked with artists

ranging from Al Di

Meola to David Bowie.

A life-long guitarist, he’s

also the author of Pro Tools Surround

Sound Mixing and composes for the

likes of Fox NFL, Discovery Channel,

Nickelodeon, and HBO.

Rich Tozzoli is a

Grammy-nominated

engineer and mixer who

has worked with artists

ranging from Al Di

Meola to David Bowie.

A life-long guitarist, he’s

also the author of Pro Tools Surround

Sound Mixing and composes for the

likes of Fox NFL, Discovery Channel,

Nickelodeon, and HBO.As projected, the 2011 market became even more aligned with players, rather than collectors, and certainly not investors.

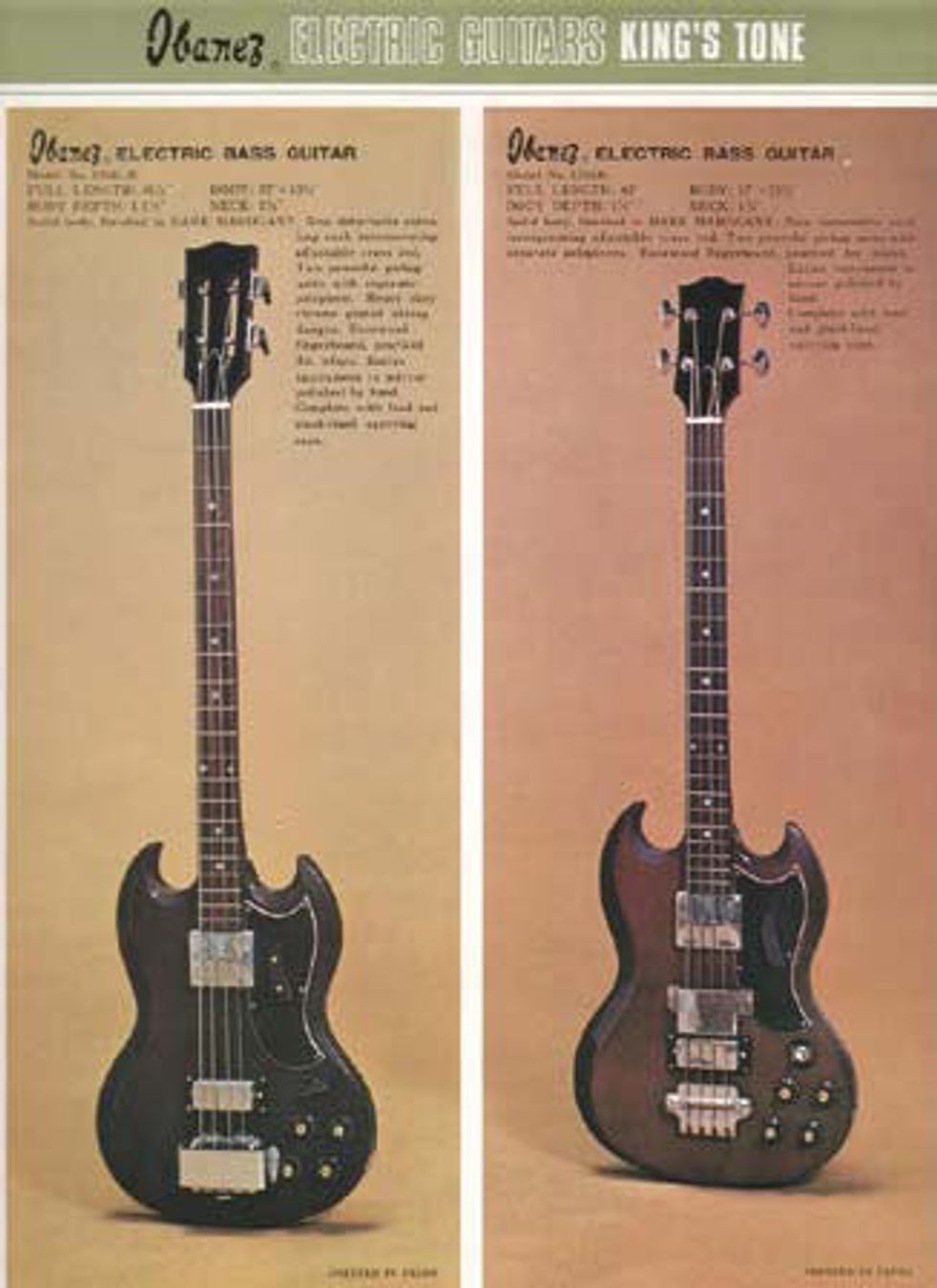

While original-design Ibanez basses have a dedicated following, the company’s “lawsuit era” 4-strings have their advocates, as well. Despite being bolt-ons, these ’70s Ibanez basses certainly bear a striking resemblance to their ’60s Gibson forebears. Image courtesy of bassoutpost.com

The pricing sweet spot in 2011 was between $600 and $4000, down from $1500 to $5000 the previous year. And this is down considerably from the 2007 numbers of $2500 to $10,000. One major change I’ve seen is that tradeshow attendance appears to have increased considerably and that tradeshow activity (buying, selling, and trading) is also on the rise. Just by looking at confirmed sales, internet auction transactions appear to have cooled a bit, even with lower selling prices. That said, it looks like in-hand prices have remained relatively static when compared to 2010. In talking with many clients, I’ve gathered that instead of opting for an internet sale by a non-dealer offering no guarantee or return privilege, people seem willing to pay a premium for a face-to-face deal—which amounts to an extra 5-10 percent— simply for peace of mind.

What’s Hot. There was not a single bass I put in my crosshairs as a “must buy” in 2011. Provided a bass played great, sounded great, and was correctly priced—it sold. Refinished Jazz basses, 4001s, and Thunderbirds continued to have a short shelf life, while refinished P basses tended to hang around just a smidge longer. Most any other refin bass had to be cheap to sell. Dead mint to firewood Thunderbirds from the ’60s and 4000 series Rickenbackers have had constant activity, while J basses and ’60s P basses have seemingly come back to life.

The key here is pedigree versus price—they simply have to be in sync. Industry-standard boutique basses have also been sturdy sellers, provided they were still pretty, played great, and priced correctly. Alembics under $5000 and USA Laklands, Spector, and Tobias basses under $2500 all traded steadily. I’ve seen Sadowsky, Fodera, and Warwicks remain as steady swingers with Warrior basses gaining some traction. And while early G&L and ’70s Gibsons continued to sell, the surprise of the bunch has been post-lawsuit, original-design Ibanez basses— extremely good instruments that have quite the following. Mismatched necks and bodies, hot-rod components, and refins on mishmash basses from the ’50s through the ’70s have been hot. This is a huge contrast to even two or three years ago when pedigree was everything.

What’s Not. 2011 continued to show pain in the marketplace. Just one example of this was the slowdown of 1970s P bass sales. Also, with a few exceptions, gear over $10K—even if priced fairly—did not seem to move. Realistically priced T-Birds and 4000 series Rickenbackers from the ’60s were the exception, along with the odd extremely rare or extremely clean instrument. While both Rickenbacker and early Music Man basses sold steadily, the former came down about 20 percent and the latter dropped in price by 15 percent. Epiphone basses from the ’60s—though cooler than their Gibson comps—witnessed triple the shelf life when comparably priced. And Christmas catalog basses—always popular because of their cheap nostalgia—have been dead in the water and most can’t be given away. Old may equate to cool, but not necessarily desirable. Just ask the SD Curlee owner who couldn’t get $300 for his bass at two guitar shows.

Projections for 2012. There is a lot of gear to buy at relatively sane prices—prices I expect to remain static. Because it’s the musicians buying instruments and not the speculators, gear trading has never been more fun. The tradeshow crowd seems to be enjoying themselves. Though not in dollars spent, it’s almost a throwback to the early 2000s in terms of vibe. The flavor-of-the-week club appears to have settled down and the up-and-down spiking of sales by make and model has leveled out. Traditional gear is the hot commodity and many players are coming back to 4-string basses, with basses sporting more than five strings having become a rarity compared to a couple of years ago.

I’m calling 2011 “the year that people did not understand.” I find used Rickenbacker 4003s listed online at $1500 to $2700 for the exact same bass, and I saw a late-’60s refin Precision listed for $8000. Basses with flaws are being tagged at top dollar, so going forward, the principle of quality-versus-price will become even more significant. Sorry, but you won’t sell a B00 StingRay to a dealer for $2700, when he has the same one for $2200.

The Low Down… We’re Undecided. Talking with my dealer buddies and many of my player clients, it seems everyone is looking for something different and nothing different at the same time. While staples will continue to sell just because people crave a different instrument, folks are not looking for the next trendsetter. Hamers and Jacksons have been trading in-and-out against StingRays— but is this bucking the trend or becoming the trend?

Live auctions have been showing up at major tradeshows. Will this be the norm or a flash in the pan? The jury is out on what’s in store for us, but boy, the opinions are in. Let’s just say there’s no joy in Mudville with this one, so let’s wait and see.

Kevin Borden has

been playing bass since

1975. He is the principal

and co-owner, with

“Dr.” Ben Sopranzetti, of

Kebo’s Bass Works (visit

them online at kebosbassworks.com). You can reach Kevin at

kebobass@yahoo.com. Feel free to call

him KeBo.

Kevin Borden has

been playing bass since

1975. He is the principal

and co-owner, with

“Dr.” Ben Sopranzetti, of

Kebo’s Bass Works (visit

them online at kebosbassworks.com). You can reach Kevin at

kebobass@yahoo.com. Feel free to call

him KeBo.