Dream Theater’s twin shred deities—guitarist John Petrucci and bassist John Myung—discuss the hoopla over founding drummer Mike Portnoy’s departure, their tendon-thrashing hand workouts, and the recording of their latest epic, A Dramatic Turn of Events.

Dream Theater bassist John Myung (left) and guitarist John Petrucci. Photo by Michael Lavine

A little over a year ago, just as the members of prog-metal giant Dream Theater were contemplating the logistics of their next album, the unexpected—no, the unthinkable—happened. Drummer Mike Portnoy, a founding member and the band’s spokesperson and leader since its inception at Berklee College of Music in 1985, quit. Portnoy had toured with Avenged Sevenfold in the spring of 2010 after the band’s drummer, Jimmy “the Rev” Sullivan—who idolized the Dream Theater drummer—passed away unexpectedly. Miscommunication and dissatisfaction must’ve abounded in both bands, because Portnoy apparently thought he had a chance of becoming a full-time member of the younger, more commercially successful AX7, but guitarists Zacky Vengeance and Synyster Gates claim they hired Portnoy primarily to honor their deceased bandmate. By the time Portnoy realized the direness of the situation, Dream Theater had moved on.

Shortly after Portnoy gave his notice, seven of the world’s top drummers—Mike Mangini, Marco Minnemann, Virgil Donati, Aquiles Priester, Thomas Lang, Peter Wildoer, and Derek Roddy—were invited to New York City to audition for the vacant slot. To make the already nerve-racking auditions even more terrifying, the band filmed the three-day process for a documentary-style reality show called The Spirit Carries On. The grueling audition consisted of three parts: Phase one covered songs, phase two entailed jamming (presumably in odd meters that aren’t even in the same universe as the 12-bar blues!), and phase three dealt with riffs. In the end, Berklee College of Music professor Mike Mangini got the gig.

On September 13, 2011, Dream Theater released A Dramatic Turn of Events, which was produced by guitarist John Petrucci. We caught up with Petrucci and bassist John Myung to broach the touchy subject of Mike Portnoy, get more details about the audition process and the new album, and talk gear.

First, let’s discuss the question on everyone’s minds: Were there signs Mike Portnoy had been thinking of leaving prior to his announcement?

John Petrucci: No. It came out of the blue. We said everything we could to try to convince him that it was a mistake, but ultimately it was something he had to do.

John Myung: In hindsight though, you could kind of connect the dots. When you look back, you can pick up on vibes and stuff. But it wasn’t like you thought it was actually going to happen.

I’ve read that Portnoy says when he later reached out to you guys to try to reconcile, he only heard back from your lawyers.

Petrucci: By that point, we had reconstructed our infrastructure and moved on in a major way. We filmed the movie, had the studio time booked, and chose Mike Mangini who then left his tenured professorship at Berklee. And then Mike came to us and said, “Hey, I want to come back.” We were like “Really? Are you kidding me—after all that?”

Have you guys talked?

Petrucci: It’s ongoing. When you’re a band that’s been together for this long, there are a lot of business things involved. It’s very similar to a divorce; you have to work out all of the details.

Let’s talk about the drummer auditions. What songs did you choose and why?

Petrucci: Well first of all, we didn’t want to overwhelm everybody and have them learn an hour’s worth of music or anything like that. We wanted to make sure we had a varied array of songs that make up our style.

Myung: And the different elements that we incorporate into our live shows. We also wanted to get a sense of how they would approach the different songs.

Petrucci: We chose “The Dance of Eternity” for its real technical and progressive aspect. Then we chose “A Nightmare to Remember,” because it’s important to have a drummer that can kick hard, play double bass, and do all of that great stuff. “Nightmare” not only has that but it also has more sensitive groove moments. And then we chose “The Spirit Carries On,” which is moodier and simpler, and all about the feel and the flow. That was a good balance. If a drummer can play all of those songs with us and have them feel comfortable, then we’re on the right track.

When you watch the auditions, you can hear that some of the drummers added their own twist to the songs—and you can tell that didn’t go over so well.

Petrucci: I think for any musician joining an established band, the first focus should be on making it sound like the band. If you come in and take a completely different approach and change the style up and start doing your own fills, it might be something cool technically and musically, but it’s ultimately not going to leave a really good first impression. We’re looking for a new drummer and we have a discography of many, many songs plus a worldwide fan base. It’s not only us as band members, but it’s also our fans who are going to want to hear the songs played and have it sound like Dream Theater. The audition environment is not really the place to try and change things up and reinvent our sound.

Myung: We were looking for more of a classical interpretation. It was more like, “Let’s run through these songs and see how great and natural they feel,” rather than looking for the improvisational side of it. You can have two people play the same part and it feels different. Every drummer has their own way of interpreting and phrasing things. The one thing unique about every musician is how they interpret the subdivisions. How they group the notes and cluster the subdivisions.

Dream Theater (left to right): Mike Mangini, Petrucci, James LaBrie, Myung,

and Jordan Rudess. Photo by Michael Lavine

Like where they’re hearing the accents in, say, an asymmetrical phrase?

Myung: Yeah. Like, would you think of 9/8 as 6/8 then 3/8 or 3/8 then 6/8? It’s a total feel thing, but it’s sort of like, “Are we on the same page, musically?”

Tell us about the writing sessions for the new album.

Myung: It reminded me of the early days, when it was just me sitting in front of John and Jordan [Rudess, keyboards] and saying, “I’ll play this part, you play this part, and we’ll record it.” A lot of the early stuff was stuff I would first work on with John and Kevin [Moore, original DT keyboardist] and then we would bring it to the band. But once our [1992] album, Images and Words, took off and went gold, we were just like this machine. We started touring and writing and doing everything together.

So, in some ways, this was like we were back to the beginning. It was a combination of writing as a group and not as a group. The sessions were really mellow and laidback. We were all playing at acoustic volumes, which made the dynamics of the communication different. It felt less on the go and more meditative.

Petrucci: I had stuff that I worked on ahead of time—demos, songs, and my riff library—but, ultimately, John, Jordan, and I went into the studio and wrote together. As we were writing, we demoed it all. I programmed the drums using Superior Drummer in Logic. After we finished the songs, we sent them to Mike Mangini. About two-and-a-half months later, when we came to record, he had templates of all the songs—all the tempo maps and markers. It’s pretty incredible to watch and record somebody like that. He came in and brought everything to life. It’s a lesson for all professional musicians out there—not only about being incredibly skilled and gifted, but also about being prepared.

How do you balance maintaining and/or furthering your prodigious technique while working on the demanding live set and committing it to memory?

Petrucci: Things go in stages. Right now, my focus is on the fact that I know I have to tour, and the first show is September 24, so I have to be able to play such and such songs. There’s a whole process of learning them—isolating the guitars and going back and learning what I played—then memorizing it and practicing the difficult parts. It’s not the time to be searching out and practicing new things: The focus is the short-term goal. Once I get comfortable and I’m on the road, or when the tour cycle is done and I’m home, then I can take a deep breath and start asking questions again, start learning new things.

Myung: I’ll know what the set is going to be at least a month prior to a tour. Then I put myself on a schedule where I at least run through every song once a day, going through the set for two or three hours. Some of the songs are really long, so it can take over ten minutes to get through it once. Even if you’ve played it for an hour, you’ve only gotten through it five times or so. Our set is like two hours, and we’ll have a master set with extra songs in it, so maybe there will be—from start to finish—like, three hours of material to run through. Then, slowly it starts to come together.

Apart from just running through the set, I also have to get my hands to do what I want them to do, which is a whole other thing where I just warm up. I have a certain procedure that I do with my hands before I feel totally dialed in. It’s two or three hours of subtle movements. And it’s not anything that I learned from a book, it’s just playing.

Are you able to find time to do this every day?

Myung: It’s a part of my life now, so I need to do it. And before every show I have to do it.

You run through the whole two-hour routine before every show?

Myung: Yep. Absolutely. Usually, we’ll drive overnight on a bus, check into a hotel, and soundcheck will be sometime after 4 o’clock, and then we’re usually on at 9. Between soundcheck and the actual showtime—as soon as soundcheck is over—I disappear and find a room, then immediately start my sequence. It really has to be that way, because you can’t give it your all and feel good about what you’re doing if your hands, if the physical side of things isn’t ready. You have to condition yourself to be able to play the way you want to play.

Petrucci with one of his Music Man JP6 guitars. Photo by Michael Hurcomb

John P., in the past you’ve said you used to think of alternate picking and legato playing as two separate approaches, and that legato playing almost felt like cheating because you don’t have to pick every note. Later, you combined both approaches to play at what you call “hyper speed.”

Petrucci: Basically, if you’re alternate picking consecutively and then you stop to leave room for legato, the direction your pick left off and starts up again is where it normally would be if you were alternate picking, like where the downbeat is.

Do you mean like “down-up” then legato then starting again “down” on the next beat?

Petrucci: That’s the simplified version, but yeah, the downbeats still fall where they would normally fall, like on the beat.

I know you also make it a point to practice the same line starting with both a downstroke and an upstroke. Do you do that with these types of combination lines as well?

Petrucci: Yeah. It’s important to work on that sort of thing. I think this type of thing is a bit more natural. If you’re improvising it’s where it ends up, depending on where you’re starting. But it’s always good to practice things starting with different strokes so that you feel comfortable both ways. It’s funny, I was talking to Mike Mangini about this. He’s very into technique and plays at a highly developed level, and alternate picking is a very similar parallel to the left-right hand-foot coordination that drummers employ. Like if you have a weak hand or a weak foot or a weak upstroke, and you practice to make it strong and even.

Let’s talk gear now. Tell us about your Music Man instruments.

Petrucci: I started working with Music Man over 11 years ago, and they’re an unbelievable company. We started with the original signature model, and now we have a whole line. Instead of discontinuing a model, we keep it available for sale. The cool thing is that they’re all unique in some way. It’s like having different spices in your spice rack.

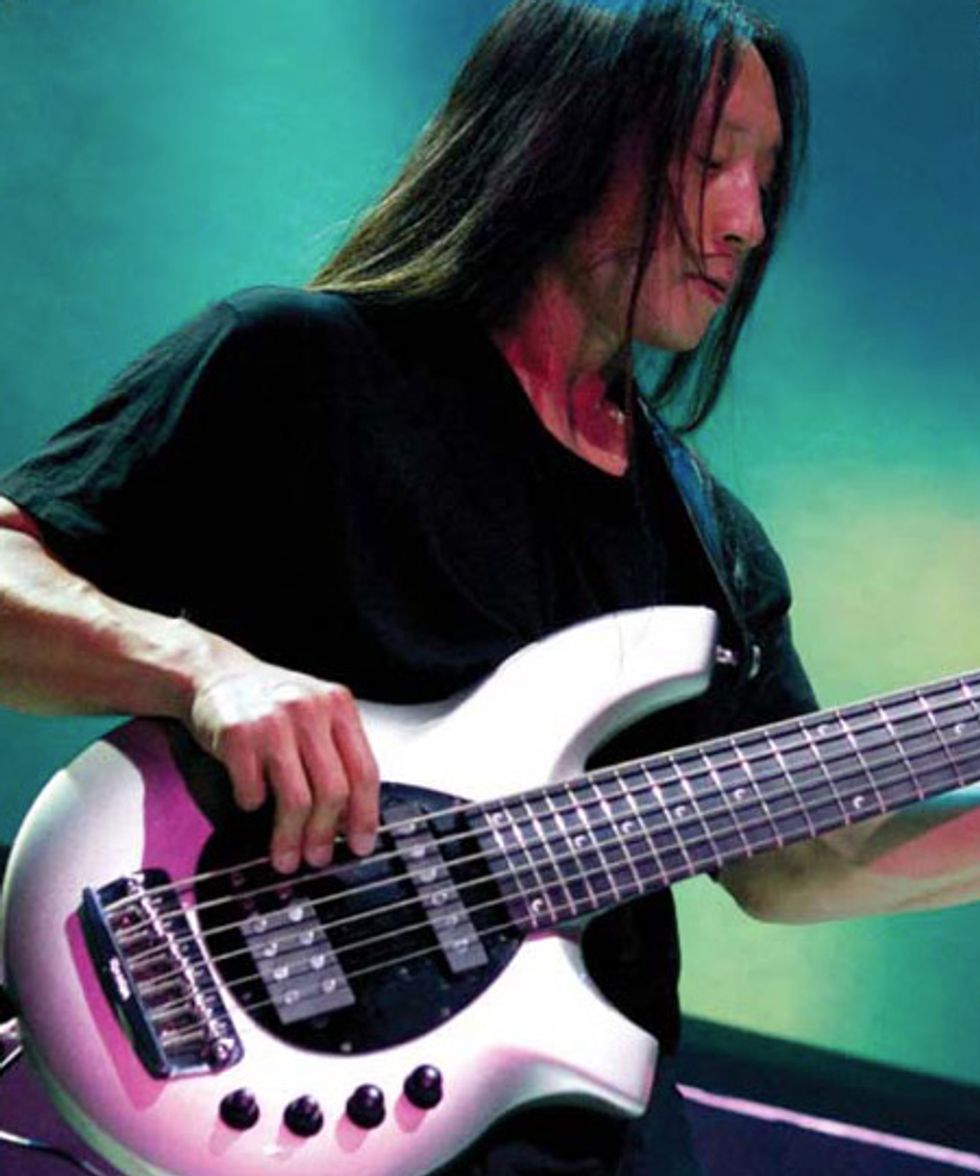

Myung: I’m using custom Music Man 6-string Bongo basses. I’ve had the one I’m playing now since last August, and it’s the best bass I’ve ever played.

Myung with one of his Music Man Bongo 6-string basses. Photo by Michael Hurcomb

From what I understand, it’s the first 6-string bass Music Man ever made.

Myung: That’s right. The original Bongo prototype was a 6-string, but the neck and the body had been increased proportionately. I was living with that for a while, but it got to the point where it didn’t feel completely right, so we went with a tighter spacing and I went with superimposing six strings on a 5-string Bongo. That was close, but I wasn’t completely sold on it, so I kept playing the standard 6-strings, and then during the last tour I decided maybe the magic formula is keeping the body of the bigger scale but using the 5-string neck. That proved to be the winning combination. It’s basically the 5-string neck dimension, but with six strings. It’s really changed my world and made my life so much better.

John P., you’re partially responsible for making the Mesa/ Boogie Mark IIC+ the most sought-after vintage Mesa, and you’ve consistently used Boogie amps over the years. Your rig now features the Mark V, which has Mark IIC+ and Mark IV modes. Can the Mark V replicate those amp tones exactly?

Petrucci: It’s really, really close. You can’t even tell the difference. The whole record was done with the Mark V. All the rhythm guitars were done with the Mark IV mode, and all the guitar solos were done with the IIC+ mode. It sounds so incredible. I’ll have the Mark IV and IIC+ in the studio and A/B them, and not only can you not tell the difference, in many cases, the Mark V beats them with the improvements they made.

How so?

Petrucci: The Mark V uses newer parts and technology and has a more focused sound, in general.

Both of you have also incorporated the Fractal Audio Axe-Fx into your rigs.

Petrucci: When I went into the studio, the Fractal guys came down and mic’d up my Mark V. We got this great guitar sound and they modeled it as closely as they could. I was then able to use that bank of Axe-Fx sounds to comfortably write and demo the album. It was incredibly convenient and simple, and it sounded amazing. Once the writing process was complete, I then mic’d up the Boogie and rerecorded all the guitars with the Mark V. Here and there, we ended up keeping the scratch guitar performances with the Fractal if it was something that just had that certain performance magic—mostly some clean stuff and a couple of short lines.

Myung: Right now, the Axe-Fx Ultra is the hub for all my effects. In the studio, I did a lot of modeling with the guys from Fractal Audio. We modeled a whole bunch of things that I needed but would be too hard to take on the road—stuff like a Pearce BC1 preamp, which I really like.

Photo by Rick Wenner

Is that the one Billy Sheehan uses?

Myung: Yep.

Could the Axe-Fx eventually replace your amps?

Myung: Not for bass—at least not now. But it’s great as far as providing supplemental characteristics. What I’ve found is that, to get a cooking bass sound, what you need is a heat source. You really need tubes and heat, because it offers warmth, dynamics, and natural compression.

Petrucci: The Axe-Fx is an awesome unit—it’s replaced most of the effects in my rack, and it’s doing all of the delays and harmonies. I have a small pedalboard for all of the front-end stuff. Ultimately though, when it came time to track the guitars, for me, I don’t know if it’s too soon to call it old-school, but the whole guitar-into-an-amp-into-a-cabinet-pushing air-being mic’d thing—I’m addicted to that. It’s something that I’ll never stop doing. Every time I try something like a speaker simulator or a modeling thing, as great as the technology is—and it gets better and better and better—I’m still married to that. There’s nothing better.

John Petrucci's Gearbox

Guitars

Music Man John Petrucci signature JPXI 6-string, Music Man John Petrucci Ball Family Reserve (BFR) 6-string, Music Man JP6 6-string, Music Man JPXI 7-string (with low B string), Music Man JP BFR 7-string (with low B), JPXI 6-string (in D tuning—standard tuning dropped a whole-step), Music Man John Petrucci BFR (in D tuning), Music Man John Petrucci BFR baritone (in A tuning), Taylor 30th Anniversary 712ce

Amps

Mesa/Boogie Mark V heads, Mesa/Boogie Rectifier 4x12s with Celestion Vintage 30s

Effects

Fractal Audio Axe-Fx Ultra (at press time, tech Maddi Schieferstein was working with Fractal Audio’s Matt Picone to program an Axe-Fx II for Petrucci), Dunlop CryBaby DCR2SR rack wah, Majik Box Body Blow, Boss PH3 Phase Shifter, MXR EVH117 Flanger, G Lab BC1 Boosting Compressor, Ernie Ball 25K Stereo Volume Pedal

Strings, Picks, and Accessories

Ernie Ball .010–.046 Slinkys (for standard tuning), .056 for low B on 7-string guitars, Ernie Ball Slinkys for D tuning sets (.010, .013, .017, .028, .042. .052), Ernie Ball Slinkys for A baritone tuning (.012, .016, .022p, .036, .048, .064), Ernie Ball Earthwood Extra Lights (for acoustic), Jim Dunlop Ultex Jazz III 2.0 mm picks, TC Electronic PolyTune, Furman AR-PRO AC line-voltage regulator, Axess Electronics CFX4 Control Function Switcher, Axess Electronics GRX4 Guitar Router/Switcher, Axess Electronics FX1 MIDI controller, Framptone Amp Switcher, custom Mark Snyder interface/switcher, Mogami cable with Neutrik connectors, Finger-Ease guitar-string lubricant, DiMarzio ClipLock straps

John Myung's Gearbox

Basses

Music Man Bongo 6-string basses

Amps

Demeter HBP-1 preamp, Demeter VTHF-300M tube power amp, Demeter VTDB-2B tube DI, Radial JD7 Signal Distribution Amplifier, Radial JDX Reactor direct box/speaker simulator, Demeter BSC-212 2x12/1x8 cabinet, Mesa/Boogie Dual Rectifier head and 4x10 cab (for dirty tones)

Effects

Fractal Audio Axe-Fx Ultra, Demeter HXC-1 HX compressor, Little Labs IPB Jr. Phase Adjuster, Moog Taurus 3 bass pedals, Fractal Audio MFC-101 MIDI foot controller, Ernie Ball volume pedal

Strings, Picks, and Accessories

Ernie Ball strings (.032, .045, .065, .080, .100, .130), Furman AR-1215 AC line-voltage regulator, Shure UR4D wireless, Whirlwind Selector A/B box, Korg DTR-2000 tuner, Mogami cable, Levy’s Leathers straps, Jim Dunlop StrapLoks

How a small retail shop in L.A. morphed into becoming a builder of the most radical designs of the 1970s and ’80s—and then managed to redefine Reagan-era metal guitar.

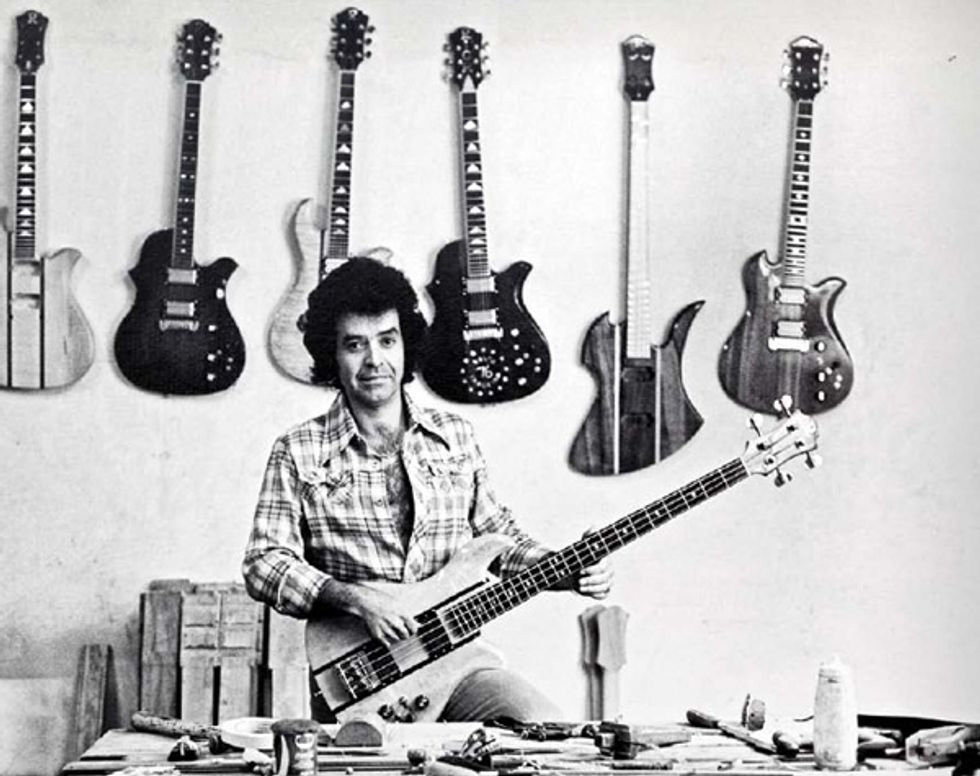

Bernie Rico Sr. with an early Eagle bass at his L.A. fabrication shop on Valley Boulevard circa 1977. A Mockingbird bass and various double-cutaway Eagle and single-cutaway Seagull 6-strings hang behind him.

Photo by Andy Caulfield

During the ’80s, the wild shapes of B.C. Rich guitars proved to be the perfect match for the over-the-top theatrics of the burgeoning heavy metal craze. The image of W.A.S.P.’s Blackie Lawless dripping in blood while clutching a B.C. Rich Widow in one hand and a skull in the other was just one of many that catapulted B.C. Rich to being the No. 1 guitar company as metal came to rule the airwaves. “The company grossed around $175,000 when I started working there and, with the [introduction of the] NJ Series, it was up to about $10,000,000 by the time I left,” says Mal Stich, who was vice president of B.C. Rich during its ascent. For this historical retrospective, Stich gave Premier Guitar a first-hand account of the company’s milestones. Additional information has been provided by Neal Moser and Lorne Peakman.

Although B.C. Rich has crafted an identity as a metal guitar company, it actually started as one of the first boutique electric-guitar makers—it was among the first to introduce neck-through-body 24-fret guitars and heelless neck joints. Many respected artists outside the metal community, including studio great Carlos Alomar (David Bowie), pop meister Neil Giraldo (Pat Benatar), and jazz guitarist Robert Conti were proponents of B.C. Rich guitars.

LEFT: An early photo of Bernardo’s Guitar Shop located at 2716 Brooklyn Avenue in Los Angeles.

RIGHT: Mal Stich with a custom B.C. Rich circa 1978. Photo by Andy Caulfield

Where It All Began

B.C. Rich’s origin can be traced to Bernardo’s Guitar Shop at 2716 Brooklyn Avenue, in Los Angeles. In the mid ’50s, Bernado Mason Rico purchased the store from the Candelas guitar shop and opened his namesake store. He didn’t work on the guitars himself—he chose to focus on day-to-day operations—but instead hired luthiers from Paracho, Mexico, which is widely regarded as the guitar capital of that country. Rico helped many of these luthiers gain residence and naturalization as citizens of the United States. Rico’s son Bernardo “Bernie” Chavez Rico, an accomplished flamenco guitarist, did become involved with the guitar making, however.

Father and son brought bodies in from Mexico, had them painted and assembled at the shop for mariachi, classical, and folk musicians. By the early ’60s, folk music had become popular and folk artists started bringing in their acoustic steel-string guitars to the shop for repairs. Word spread, and throngs of musicians like Barry McGuire and David Lindley started bringing in Martins and Gibsons for work and daring modifications, such as disassembling a Martin D-18 and putting in a 12-string neck.

The folk boom led to the shop’s production of steel-string acoustics, which featured Brazilian rosewood back and sides, Sitka spruce tops, and Honduran mahogany necks with Gaboon ebony fingerboards. Although these early guitars were reportedly rated higher than new Martins at the time, they had some minor issues. Because they didn’t have an adjustable truss rod, the guitars were often brought in later to have the fretboard removed and a truss rod installed. They also had very thin spruce tops that sounded nice but were known to crack and move from 1/16" to 1/8" into the soundhole if too much string tension caused the neck to fold into the body. These issues were quickly addressed without question, and problem instruments were repaired or replaced even many years past the one-year warranty.

In 1968, Bernie made his first electric solidbody using a Fender neck. This led to his first attempts at guitar production in the form of about ten Les Paul-shaped guitars and basses modeled after the Gibson EB-3. Around 1972, Bernie and an employee named Bob Hall started developing a model they called the Seagull (which has no connection to the Godin Guitars acoustic brand). It was the company’s first production electric guitar, and it came to market in 1974. Up to that time, the store’s phone greeting was “Bernardo’s Guitar Shop.” One day, Stich answered the phone with, “B.C. Rich,” and some think that’s the moment the company name changed and it became a full-fledged guitar manufacturer with a mission.

“B.C. Rich’s intention was to make a production-line custom guitar with high quality and craftsmanship that was very expensive for the day,” says Stich. “In 1977, they were $999 retail—and you were paying more than retail if you could actually find one.”

Although, B.C. Rich was often referred to as a custom shop at the time, it wasn’t custom in the conventional sense of the word. “The guitars were handcrafted, but they were still production guitars. People might request special inlays or maybe Bartolini Hi-A pickups instead of DiMarzios, but basically it was a production-line guitar,” explains Stich. The company had facilities in both California and Tijuana, Mexico. All the workers were from Mexico, and both shops freely interchanged parts. For the electric guitars, Bernie would send wood, fretboards, frets, inlays, glues, and other materials over to Mexico, and then drive down once a month to pick up the assembled guitars, which were then painted and finally assembled in L.A. The steel-string acoustics, however, were made right there in L.A.

B.C. Rich luthier Juan Hernandez (left) shaping a body with a knife similar to

the ones at right. Photo by Andy Caulfield

Handmade—All the Way Down to the Tools

When Stich says early B.C. Riches were handmade, he means it in the truest sense of the phrase. He recalls that there were no machines in sight inside the shop—only band saws, belt sanders, block planes, spoke shaves, files, and special guitar knives that the luthiers made themselves out of highly carbonized metal. “The guys would literally go out and buy a metal slab that was probably a quarter inch thick, and they would cut it, shape it, sharpen it, and make a handle for it—usually out of mahogany. People would walk in and go, ‘Where’s your machinery?’ and we’d go, ‘Sittin’ right there,’ and point at a knife. Then they’d go into the paint shop and guys would be water-sanding, finishing coats, and buffing by hand. When they cut the blanks, the sides would be glued on and wrapped with cord like in the old days, when they made violins and wrapped them with cords in France in the 1500s. They would tap shims between the cord and the wood to make it as tight as possible for the glue joints, which were always superb. The guitars would go through a process of being marked out with a pencil and a template of the shape of the guitar—we had aluminum templates and later plastic—and then they would do a cutout on a band saw. From there, the necks would be handcarved using what I call a ‘Mexican guitar maker’s knife,’ and they just hacked the [expletive] out of it. It would start out with a hammer and a chisel—bam, bam, bam—making the neck. Then they would go to the knife, and finally to a spoke shave. These guys could knock out a neck in about 20 minutes.”

|

After the body and neck were completed, the last stop was the assembly shop—where everything was hardwired. “The parts—the Varitone, the preamp circuitry, etc.—were made by hand,” says Stich. “We would go to the electronics store and buy all the parts we needed, and they would cut up the PCB boards. It was really labor intensive.”

Intricate Circuitry

Noted luthier Neal Moser, who had developed a reputation as the go-to guy for hot-rodding guitar electronics, joined the company in 1974. Over the initial dinner meeting at Bernie’s house, Moser sketched out the circuitry and layout for a new design on a piece of cardboard. He soon went to work for B.C. Rich as an independent contractor. His dinner-table design—which consisted of master volume and tone controls, a built-in preamp, a 6-position Varitone, and coil taps—was implemented on the production Seagull guitar.

B.C. Rich’s electric offerings were originally equipped with Guild pickups, but the company later switched to DiMarzios, which Stich says, “added a whole different reality to the guitars. The Guilds had this ’50s or ’60s sound, whereas the DiMarzios had a new sound to them. They also worked better with Moser’s circuitry.”

Wilder and Wilder Shapes

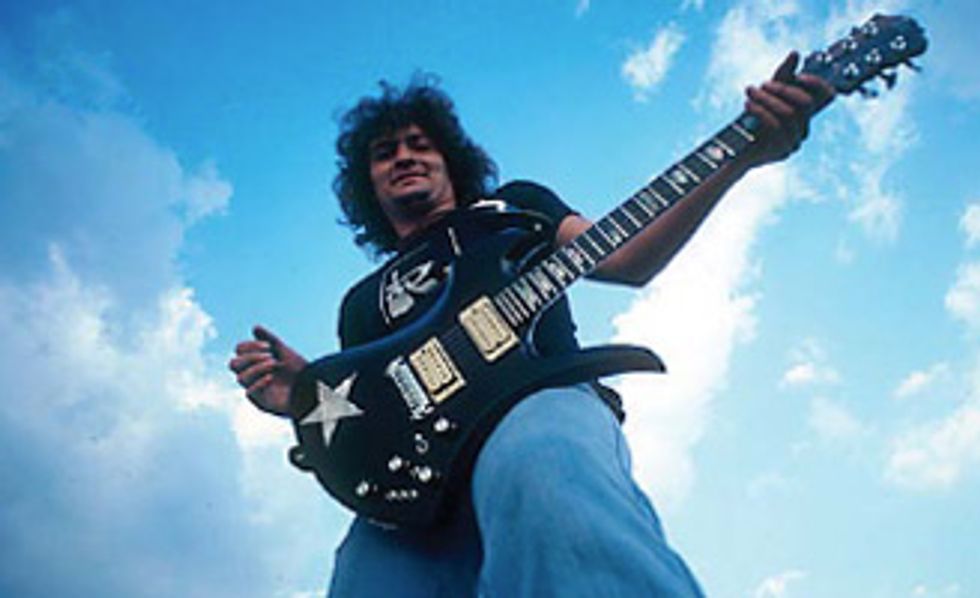

B.C. Rich guitar bodies always pushed the envelope of guitar design, and as the years progressed, the shapes got even more extreme. The Seagull’s toilet-seat-inspired shape was daring for the time, but fairly conservative in hindsight. And though it was well received, the protruding point on the upper body was uncomfortable for some players because it poked into your torso at certain playing angles. This led to the creation of the Eagle, which had a more conventional Strat-like shape, but with the Seagull’s treble-side cutaway. Another version of the Seagull that jettisoned the sharp point was also later produced. In 1975, the company introduced its first radically shaped guitar, the Mockingbird, which was inspired by a shape drawn by Johnny “Go Go” Kallas and named by Moser.

In 1977, while Bernie was in Japan, Moser went into the woodshop one day and crafted the company’s edgiest design to date—the 10-string Bich. According to Stich, when Bernie returned to the shop and saw the new project, he got upset and yelled “You guys don’t design guitars without me!” The model’s name stems from a trip Moser and his wife made to the county fair. “They noticed some girls wearing charms on their necklaces that read ‘Rich Bitch.’ They agreed that would be an ideal name,” recalls Stich. “Of course, the ‘T’ was dropped.”

This five-piece, koa-bodied 1979 Mockingbird features an intonatable Leo Quan Badass bridge and multiple knobs and toggles for the built-in preamp and its phasing, tone, and series/parallel operation options.

This gorgeously quilted 1981 10-string Bich features two preamps controlled by six knobs (Master Volume, Master Tone, neck-pickup volume, a 6-position Varitone, and Volume knobs for both preamps) and six toggles that govern pickup selection and series/parallel operation, phasing, and activation of the preamps. The guitar has unison strings for the D and G strings, and octaves for the B and high E.

That model led to the 6-string Bich and the Son of a Rich, an American-made economy version with a bolt-on neck and bodies machine-made by Wayne Charvel. Initially, there was some concern that dealers would reject the guitar based on its risqué name, but after some dealers from Utah—the most conservative state in the Union—gave it the green light, the name stuck.

Introduced in 1981, the company’s next guitar, the Warlock, featured a shape inspired by the Bich—and it went on to become one of the most iconic B.C. Riches. The Widow, designed by Blackie Lawless, and the Stealth, designed by Mockingbird user Rick Derringer, followed in 1983.

By that point, B.C. Rich had a complete catalog of distinctive instruments, and it wasn’t long before overseas companies like Aria were creating B.C. Rich knock-offs. Bernie went into survival mode and flew to Japan with Hiro Misawa to set up the B.C Rich NJ series, which stood for “Nagoya, Japan,” where they were made. “We knocked-off ourselves, basically,” says Stich.

“The first time we went to Frankfurt [Musikmesse musical instrument trade show], we had really nice guitars and people came up to us and said, ‘Hey, that’s a copy of the Aria guitar.’ We were, like, ‘You’re kidding, right?’”

The company’s first Japanese guitars were labeled B.C. Rico and did not feature the NJ series designation. Trouble appeared soon after when Rico Reeds (makers of saxophone and clarinet reeds) sued B.C. Rich for patent infringement on the name. “We were, like, ‘Wait a minute! Rico is the guy’s real name.’ But instead of spending money on a big litigation and lawsuits, we just [substituted] an ‘h’ at the end of the name,” recalls Stich.

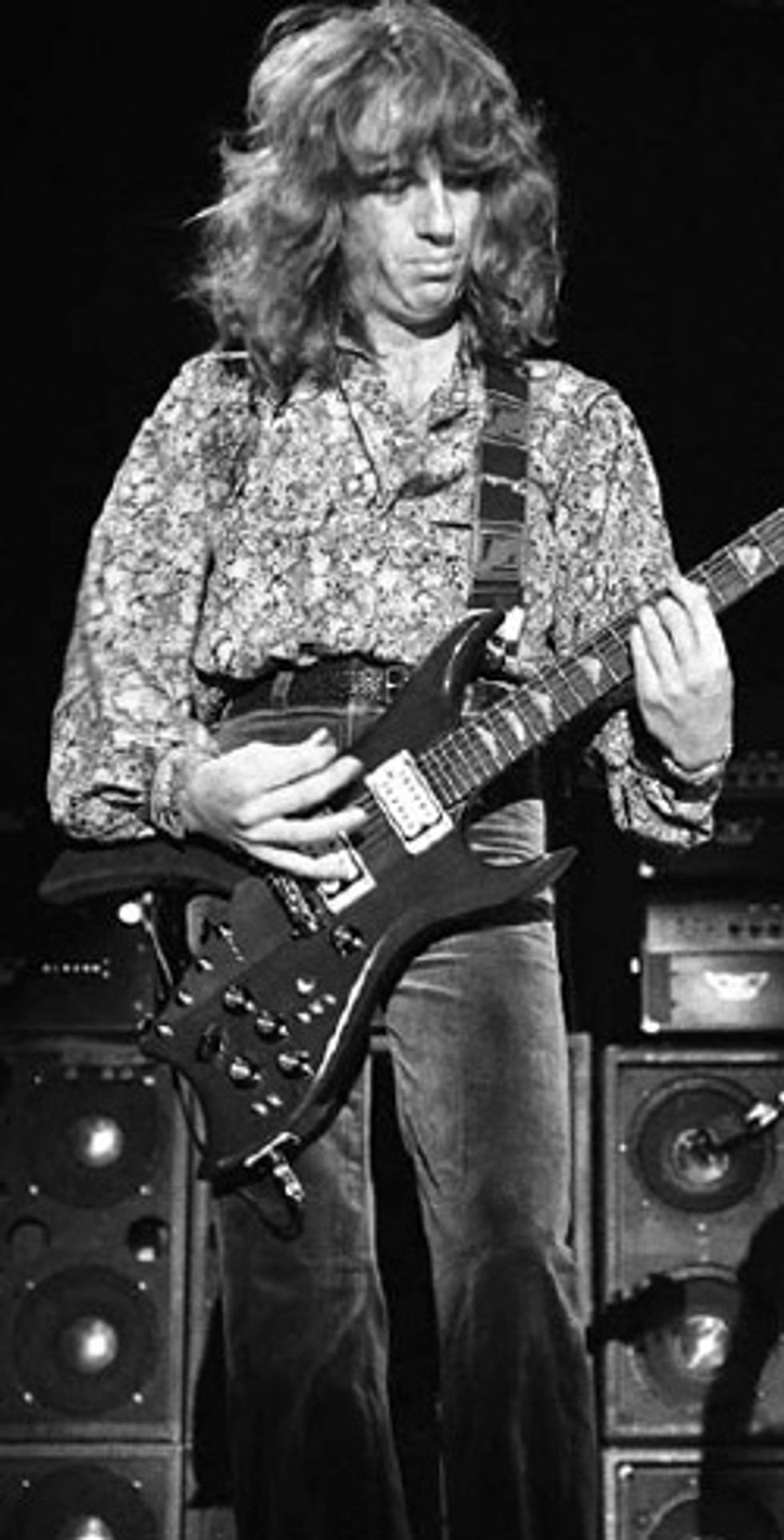

Stich with a custom-finished Mockingbird (left), and with future-star Lita Ford

playing a red-stained Mockingbird in 1980 (right).

B.C. Rich continued to produce more unique-looking guitars such as the Ironbird, the Wave, and the Fat Bob, which was shaped like a Harley-Davidson motorcycle’s gas tank. However, to capitalize on the resurgence of the Fender Stratocaster’s popularity in the mid ’80s, B.C. Rich introduced the ST series—a straightforward double-cutaway that was a noticeable departure from the company’s legacy of flashy shapes.

|

The first pivotal point in B.C. Rich’s rise to widespread recognition came in 1976, when sound engineer Bob “Nite Bob” Czaykowski picked up a maple-bodied Mockingbird—the first one ever made—for Aerosmith guitarist Joe Perry. “All of a sudden, B.C. Rich was on the map,” says Stich. “In my opinion, if it wasn’t for Nite Bob, B.C. Rich would have been another flash-in-the-pan guitar company.”

The wild shapes of B.C. Rich guitars also attracted the attention of the producers of This Is Spinal Tap. Stich put some guitars together for the production, and in so doing, unwittingly became responsible for adding a new phrase to popular music’s cultural lexicon. “There was a meeting in my office to loan the guitars and basses. I was playing with a volume knob Larry DiMarzio gave me that went to 11. I showed it to them and explained why it went to 11.” The producers used it in one of the movie’s classic scenes, and the idiom soon became immortalized in the vernacular of guitarists and rock fans the world over.

The Changing of the Guard

In the mid 1980s, B.C. Rich saw major changes that would send the company in a new direction. Stich left in ’84 and Moser left in ’85. In ’87, Bernie entered into a marketing agreement with Randy Waltuch’s Class Axe, allowing them to market and distribute Rave, Platinum, and NJ Series guitars. A year later, Bernie licensed the Rave and Platinum names to Class Axe, which essentially took over importing, marketing, and distribution of the foreign-made lines. Soon after, complete control was turned over to Class Axe and B.C. Rich’s custom shop was disbanded. Class Axe licensed the name B.C. Rich in 1989.

During this period, quality control nosedived and the B.C. Rich name suffered. Bernie was out of the company picture for a few years, and during that time he produced Mason Bernard guitars— handmade acoustic-electrics and Strat-shaped electrics. In 1993, Bernie regained ownership of B.C. Rich and made a concerted effort to restore the company’s name. Sadly, on December 3, 1999, he passed away from a sudden heart attack. Subsequently, the company went to his son Bernie Jr., who turned over control to the Hanser Music Group in 2001 and began making guitars under the Rico Jr. name. However, he is involved with some current B.C. Rich custom-shop guitars.

As part of its recently revamped custom operation, B.C. Rich also brought famed builder Grover Jackson aboard to work on the Gunslinger Handcrafted series. The company continues to evolve and release visually striking designs that, like its legacy designs, appeal to both younger metal players and elder statesman of the genre like Slayer’s Kerry King. Its Pro X Bich model was voted Best of NAMM in the electric guitar category at NAMM 2011.

Mötley Crüe bassist Nikki Sixx with his B.C. Rich Warlock—which is outfi tted with two splittable

P-style pickups, a multitude of switching options, and a reverse headstock—at a 1983 photo

shoot in Hollywood. Photo by Andy Caulfield

The POD HD is the newest member of the family, and it’s packed with great simulations—including 22 amplifier models based on classics like the Fender Deluxe Reverb, Hiwatt DR103, and Vox AC15, as well as modern and boutique models like the Dr. Z Route 66, Bogner Überschall, and an ENGL Fireball 100.

Since debuting at the turn of the century, the digital-modeling members of Line 6’s POD family have become fixtures in both project and pro studios everywhere. Ranging from the pint-sized Pocket POD to the POD X3 Pro rackmount, POD products are available to fit nearly every budget and feature-set requirement. And the enduring appeal of the brand and the bean-shaped enclosure speak to the basic usefulness of the platform.

The POD HD is the newest member of the family, and it’s packed with great simulations—including 22 amplifier models based on classics like the Fender Deluxe Reverb, Hiwatt DR103, and Vox AC15, as well as modern and boutique models like the Dr. Z Route 66, Bogner Überschall, and an ENGL Fireball 100. It also has more than 100 Line 6 M-series effects that model both classic and obscure distortions, fuzzes, reverbs, pitch shifters, delays (with tap tempo), and EQs.

Although the POD HD is optimized for recording, it can also be used as a compact practice unit. Complete with a tuner and a 48-second looper, it practically begs you to plug in your axe and a set of headphones to start laying down tracks, overdubbing, and adjusting speed and playback.

On the Surface

With 13 knobs and 13 buttons, the somewhat intimidating-looking POD HD looks more like a deep sea rover control than a guitar effect. But with a little patience and homework, the controls and parameters quickly become second nature. The largest knobs are the same basic controls you’d find on most amps—Drive, Bass, Middle, Treble, Presence, Volume, and Master, the latter of which controls overall output. The wild card of the batch is the Tweak knob, which can be assigned to either an amplifier sound or an effect and used to modify parameters in real time as you would with an expression pedal.

The effect chain is controlled from the central LCD screen, where you can utilize up to eight effects at a time. But there’s more flexibility than just lining up effects. You can insert two amp models in your signal path and pan them left and right. These functions are manipulated via the Signal Flow View, which is controlled with the multi-function knobs below the LCD. The addition of the 4-way Nav pad allows you to effortlessly move an amplifier or effect into the desired position or loop in the signal chain.

Apart from Left and Right 1/4" outputs, there are connections for Line 6’s FBV line of foot controllers, an XLR input, a USB 2.0 jack for direct computer recording and software updates, and a S/ PDIF jack to output a 24-bit digital signal. Line 6 clearly went the extra mile to make this POD quickly adaptable to modern studio needs. I wouldn’t worry about coddling this thing either—short of a direct blow to the LCD screen, this thing looks like it can take a serious beating.

Sound Off

I put the POD HD to the test with Fender and Squier Stratocasters and a Gibson Les Paul. To monitor the effects, I used a pair of headphones and a Blackstar HT-5R. Pushing the Set List button brought up four preset lists designed by Line 6, each with 64 editable tone combinations, but you can also save up to eight total Set Lists.

The first preset on my list was “Jimi Got Gyped,” which is built around models of a Marshall JTM-45, a Univibe, a Fuzz Face, and a tape echo. The convincing tone from these very difficult-to-model sounds speaks volumes about how the POD has evolved. But the extent to which you can tweak any part of a given preset is the real leap forward. When I thought the Univibe was a touch slow, I scrolled over to the stompbox section of the Signal Flow display and used the Nav pad to kick up the HZ from 0.10 to 1.00. The correction in speed left the speakers sounding a bit bright, however, so I highlighted the amp and changed from an emulation of a 4x12 cab with Greenbacks to a 1x12 Celestion 12-H and switched the simulated microphone on the Set List. Problem solved!

Creating your own presets is simple, and the tweakability and customization possibilities are virtually endless. You don’t have to be a gear wizard to find a tone that’s suitable for your project. In fact, most of the amp namesakes serve as a very accurate general reference point that you can tailor to your guitar and output preferences. Even the weirder presets (“Otherness” and “Haunted Toys” are just two of the many I tried) are easy to use, musical, and perfect for those interested in prog rock or noise projects—especially when used with the fantastic stereo output.

Although most players will use the POD more as a recording solution than as a stompbox, you can navigate to a level control to optimize output for use with an amp. And when I routed the POD into an amp this way, it responded in a manner similar to plugging into a pedalboard and then into an amp. For instance, rolling off both the Stratocaster’s and the Les Paul’s volume knobs really affected the drive of the amp simulations in a way you’d expect from pedals going into an amplifier.

The Verdict

Whether you’re recording or practicing, the POD HD will likely deliver more than you need—and provide you with a ton of options you probably never would have considered otherwise. For a lot of studio musicians who like to work fast and on a budget, it could easily become an indispensible recording tool—something you’d grab if you could only grab one device for one of those fabled desert-island scenarios. And for tone enthusiasts who want a lot of variety at their fingertips, the POD HD rivals or exceeds the ease of use of many digital audio workstations (DAWs) plug-ins—never mind that assembling the same horsepower with plug-ins could be far more expensive, and arguably less fun to use. At $399, it may be a little steep for the more informal project musician. But if you don’t have access to a high-end studio overflowing with vintage gear or even a higher quality digital workstation with plug-ins to match the POD HD’s menu, this is an investment in inspiration and flexibility that could pay itself off in no time.

Buy if...

you love sonic tinkering and eschew recording with DAWs and plug-ins.

Skip if...

only the real modeled devices will do, or you have a complete DAW with tons of plug-ins.

Rating...

Street $399 - Line 6 - line6.com |