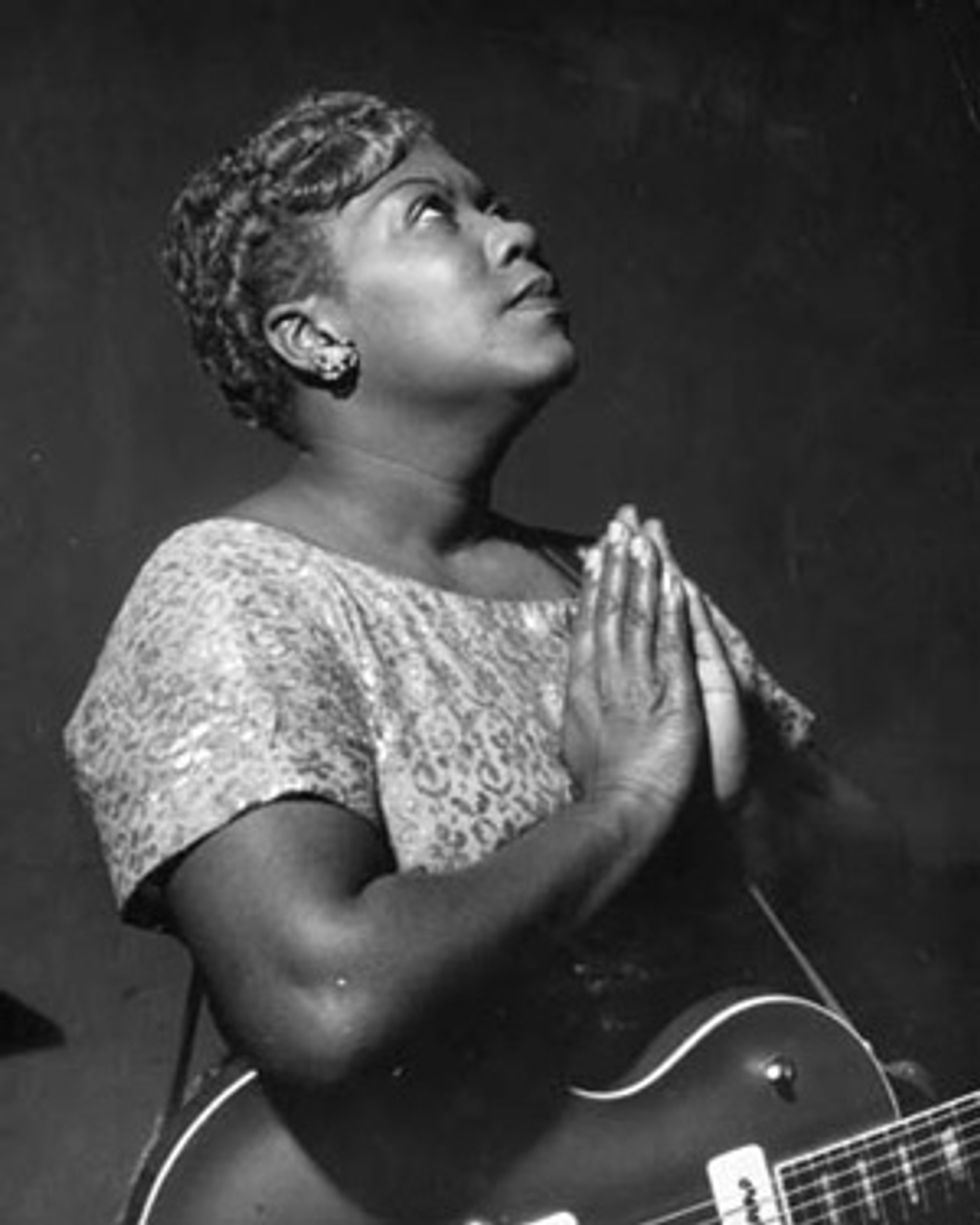

The second installment in our new series on players who’ve shaped the history of guitar highlights an incredibly soulful gospel singer who transcended race and gender and presaged rock ’n’ roll with her white Gibson 1961 SG/Les Paul and cranked tube amps.

The Early Years

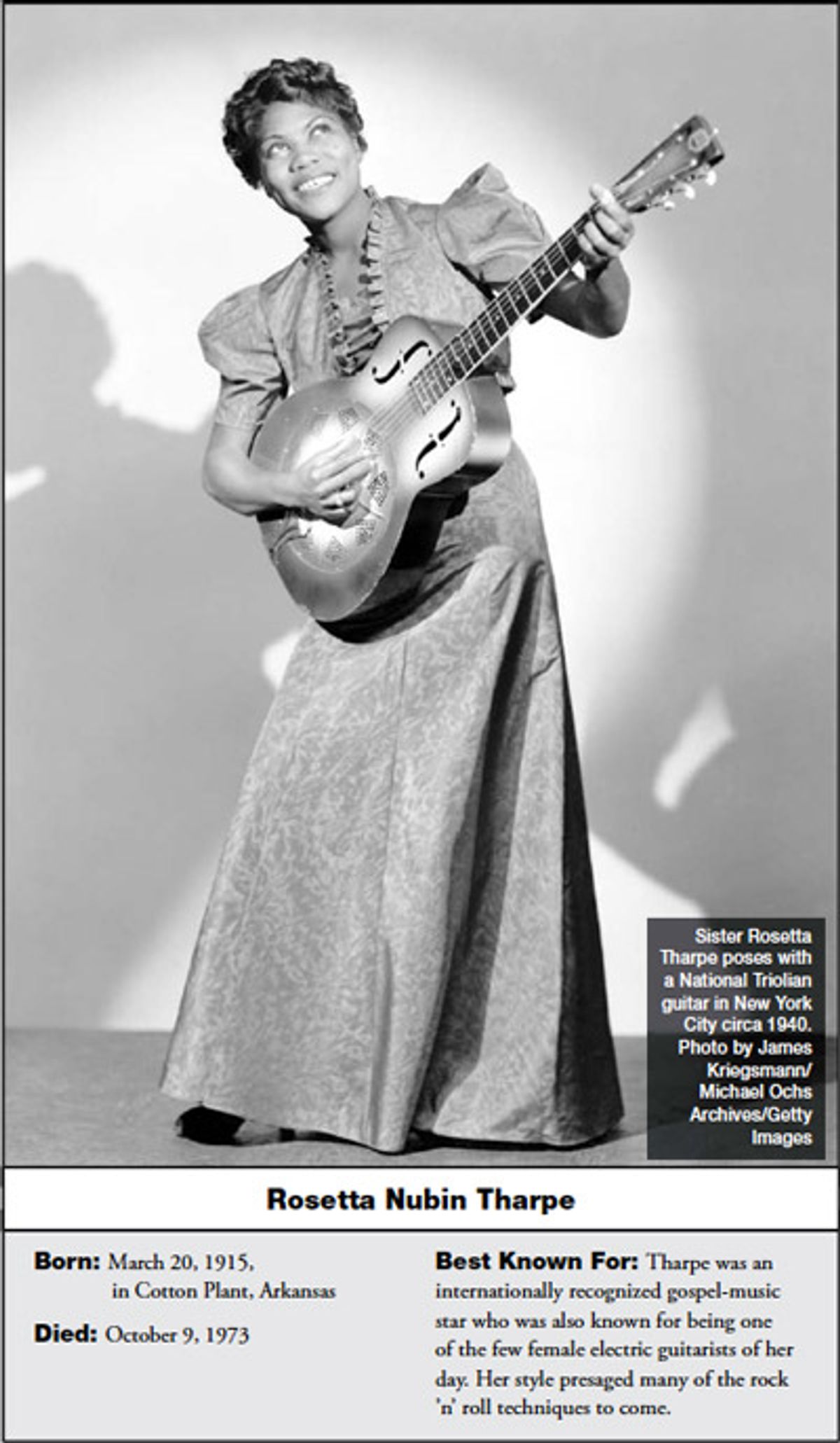

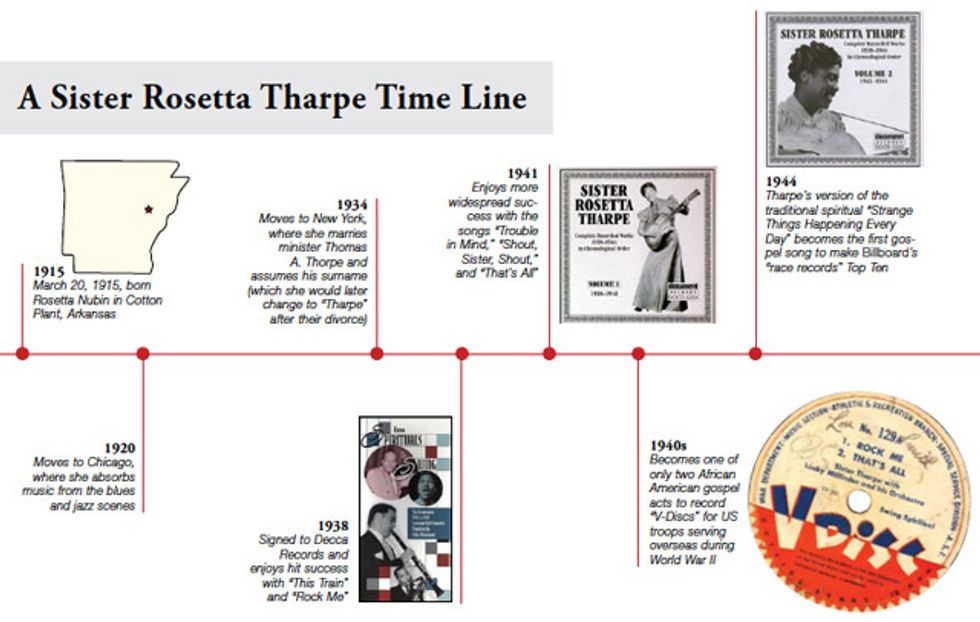

Rosetta Nubin (March 20, 1915–October 9, 1973) was born in Cotton Plant, Arkansas, and began performing at age 4, billed as “the singing and guitar playing miracle.” She began her gospel career accompanying her mandolin-playing mother, evangelist Katie Bell Nubin, who played tent revivals throughout the South. In the late 1920s, she was exposed to blues and jazz when her family moved to Chicago, and to the joy of some and the jeers of others she would eventually mix both genres with gospel music. You can hear blues bends and jazz chromaticism in the solos from her earliest acoustic solo work on Decca Records, where she was backed by “Lucky” Millinder’s jazz orchestra in the ’30s. Photos from this era show her holding various pre-electric instruments, including National archtop and steel guitars, as well as a Gibson L-5. This period is also notable because it’s when she took the surname of her first husband, preacher Thomas Thorpe, though she would later divorce him and change the spelling to “Tharpe.”

Appearances in producer John Hammond’s legendary “From Spirituals to Swing” show at Carnegie Hall, as well as gigs at the Cotton Club and Café Society, and bills with Cab Calloway and Benny Goodman helped grow her fame outside the church, much to the consternation of her more orthodox fans. Her versions of songs such as “This Train” and “Rock Me” became big hits, and even those early tunes without electric guitar had traces of what would become rock ’n’ roll rhythms.

During the recording ban enacted by the American Federation of Musicians union from 1942–44, Tharpe was one of only two gospel artists to record “V-Discs”—records intended to boost the morale of US troops serving overseas. You can hear her tearing up the acoustic on her 1944 recording of “Strange Things Happening Every Day” with boogie-woogie pianist Sammy Price. This was the first gospel song to make Billboard’s “race records” Top Ten, and some consider it to be the first rock ’n’ roll record.

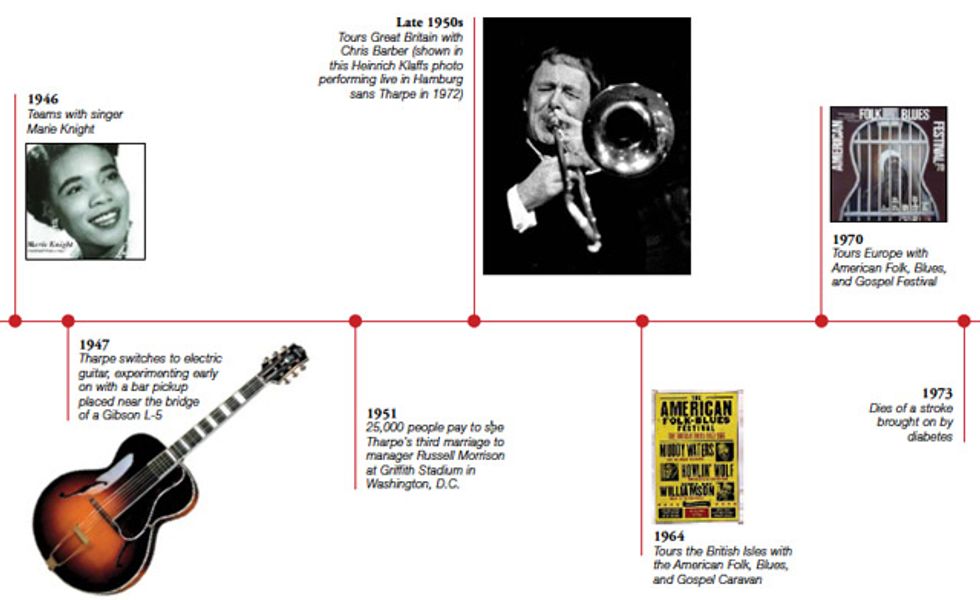

In 1946, Tharpe invited a young singer named Marie Knight onstage at one of her concerts. Knight had a strong contralto voice that blended well with Tharpe’s soprano range, and they soon had a hit with “Up Above My Head.” The pair toured the gospel circuit for a number of years, during which time Tharpe’s popularity among churchgoers peaked. The duo split in 1950, but by then Sister Rosetta was so well known that 25,000 people paid to attend her 1951 wedding to her manager Russell Morrison (her third marriage) at Griffith Stadium in Washington, D.C. The ceremony was followed by a musical performance.

Plugging In

|

By the ’60s, Tharpe’s gospel career was waning, falling short of the iconic heights of Mahalia Jackson and Clara Ward. As great a performer as she was, Tharpe found her success among the faithful was thwarted by the fact that she incorporated the sounds and rhythms of “worldly” blues and jazz, and that did not go down well with the “holy rollers.” Over the course of her life and career, Tharpe herself was torn between the religious and the secular, the sacred and the profane. Like other highprofile artists—such as Jerry Lee Lewis, Little Richard, Al Green, and Prince—she struggled to resolve simultaneous attractions to God and “the Devil’s music.” And the difficulty of that dilemma was likely compounded by the potential for exponentially greater financial success in the latter niche.

In the late ’50s and early ’60s, there was rising interest in American roots music in Britain. Chris Barber, one of the leaders of the traditional jazz movement in England, invited Tharpe to open for his band on a tour of the country. Barber could sell out shows on the strength of his own name, which made promoters reluctant to contribute more money toward bringing over Tharpe. But Barber wanted her on the tour so badly that he offered to pay her out of his own cut. The tour was highly successful, which led to even more shared bills between the two artists. As with many African-American performers of the time, Tharpe found the reception of crowds at shows and the treatment she received at British hotels and restaurants to be a breath of fresh air after the racism she had endured during years of touring America.

Tharpe's flamedtop National Triolian is now part of the collection at

The Delta Cultural Center in Helena, Arkansas. Photo by Bryan McDade

The rise of rock ’n’ roll offered Sister Rosetta Tharpe a whole new fan base. In 1957, she was quoted by London’s Daily Mirror as saying, “All this new stuff they call rock ’n’ roll, why, I’ve been playing that for years now . . . Ninety percent of rock-and-roll artists came out of the church, their foundation is the church.”

In 1964, Tharpe toured the British Isles as part of the American Folk, Blues, and Gospel Caravan, which also featured artists like Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee, Otis Spann, Muddy Waters, and “Blind” Gary Davis. Though her musical roots were similar, Tharpe was uncomfortable at first. She’d reached a certain level of glamour and sophistication and had left behind the rustic appearance and manners of the other performers. Her presentation was as polished as the hardware on her SG, which she often used like a mirror to flash light on the audience.

An abridged version of the Caravan show called The Blues and Gospel Train was filmed for British television. The producers reconfigured a Manchester railroad station as “Chorltonville,” their vision of a Deep South rural train stop. The success of the tour had mellowed Tharpe’s indignation, and she took everything—the fake hay bales, the tethered goats, and even the light rain that fell—in stride, opening very appropriately with “Didn’t It Rain.” She then greeted fans seated on the other side of the tracks with, “Oh I love you so, my English friends, forever and ever, until I leave this world. But I feel troubled. The train is gone, but I am gonna catch the next one,” before launching into “Trouble in Mind.” After the first verse, she stopped playing guitar long enough to get the audience to clap on all four beats instead of on the one and three. She also entreated Otis Spann, “Ah, play it, baby,” and immediately joined him for a soulful solo that she modestly deemed “Pretty good for a woman.”

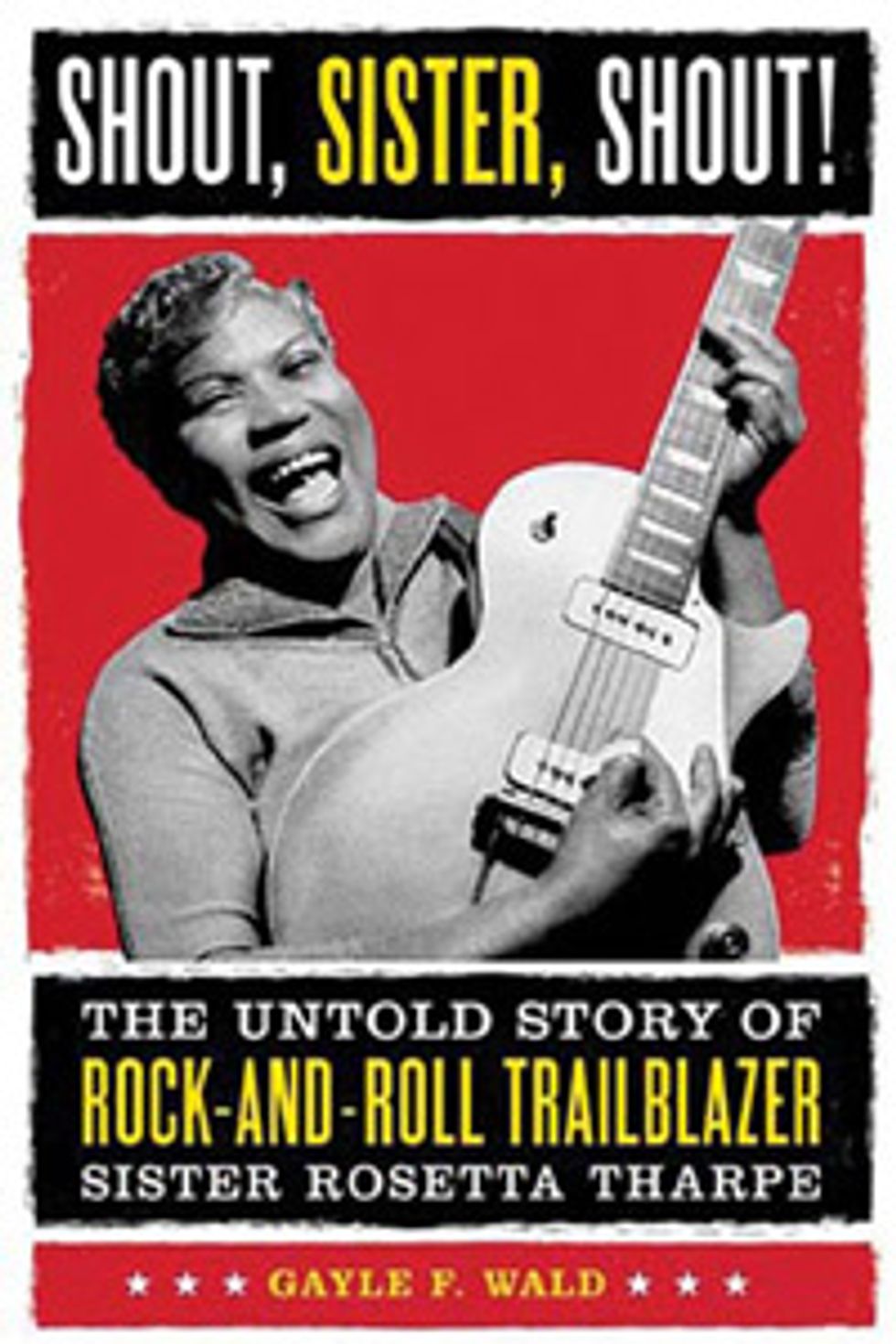

Never, Ever Daunted

Despite her modest pronouncement in Manchester, Tharpe knew just how good she was. Many gospel groups included male guitarists who lived in fear of going toe-to-toe with her. In her comprehensive biography, Shout, Sister, Shout!: The Untold Story of Rock-and-Roll Trailblazer Sister Rosetta Tharpe, Gayle F. Wald quotes Inez Andrews, who performed on many gospel programs with Tharpe, as saying, “The fellows would look at her, and I don’t know whether there was envy or what, but sometimes she would play rings around them. She was the only lady I know that would pick a guitar and the men would stand back.”

|

Many have wondered what happened to her guitars after her death, but the disposition of Tharpe’s famous white SG remains unclear. Marie Knight claims it was buried with her. Others say the man Tharpe married in front of the multitudes at Griffith Stadium was “a gold digger” who sold the guitar for ready cash after his meal ticket was gone. The latter doesn’t seem implausible, considering Morrison refused to even let go of enough money to pay for a headstone. He opted instead to have his legendary, inspiring, and influential wife buried in an unmarked grave. It was a tragic ending for a performer who helped shape the future of electric guitar and modern music as we know it.

Though there is no written account of players like Eric Clapton, Peter Green, Jeff Beck, or Mick Taylor having seen Tharpe perform, given their known obsession with blues-influenced American guitar players of that era, it’s hard to believe they weren’t influenced by this trailblazing woman who shattered the bounds of race and gender and pushed tube amps to their limits before they’d owned their first Marshalls.

Lest there be any doubt as to Tharpe’s abilities, Wald quotes a man who heard her perform many times. Alfred Miller, musical director of Brooklyn’s Washington Temple, Church of God in Christ, said, “She could do runs, she could do sequences, she could do arpeggios, and she could play anything with the guitar. You could say something and she could make the guitar say it . . . I mean, she could put the guitar behind her and play it; she could sit on the floor and play it, she could lay down and play it.”

But Wald herself said it best: “Whenever a rock or gospel or rhythm and blues musician turns the amps up, we’re living in the presence of Rosetta, who made a habit of playing as loud as she could, based on the Pentecostal belief that the Lord smiled on those who made a joyful noise.”

Sister Rosetta Tharpe was such an energetic and charismatic performer that it's impossible to fully appreciate her without watching live footage. The following online videos offer an exhilarating glimpse of the full Tharpe experience.

Tharpe tearing up a Gibson Barney Kessel hollowbody at a late-1960s gig in Germany with the Chicago Blues Allstars.

Thumbpick-wearing Tharpe gets hands clapping and bodies shaking on "Down by the Riverside" with her circa-1961 Gibson SG/Les Paul, early-1960s Gibson GA-19RVT combo, and a solo that somehow rages with righteous fury and instills heavenly joy.

Tharpe's ripping, fuzzed-out solo on her white SG/Les Paul with the side-pull vibrato unit stands toe-to-toe with the soulful, infectious conviction of her unrivaled voice.

Proving her versatility and power, Tharpe unplugs her Gibson Barney Kessel hollowbody for a quasi-acoustic version of "Up Above My Head."

Recorded live at a defunct train station in Manchester, England, that was made to look like it was in the South U.S., this recording chronicles a laughin, feisty Tharpe in heels and a long, bejeweled coat, twanging "Trouble in Mind" on her white SG/Les Paul.

Hallmarks of Tharpe’s Style

Thanks to the miracle of YouTube, it’s easy to see why Sister Rosetta Tharpe is so important to the history of electric guitar. Enter her name and “Down By the Riverside” in the site’s search engine, and the top hit (which had nearly 600,000 views at press time) opens on a shot of Tharpe performing on TV Gospel Time in a flower-print dress and a short, blonde wig. She stands in front of a men’s gospel choir and wears a white, circa-1961 Gibson SG/Les Paul with a rare side-pull vibrato strapped around her neck, acoustic-style, with the strap attaching at the headstock. As she launches into what can only be called a rocking, authoritative version of the gospel standard, fat tube distortion emanates from her amplifier. Her powerful voice rings through the choir’s joyful din with an infectious, awe-inspiring soulfulness. The camera zooms in on the guitar’s three humbuckers, and you see that she’s wielding a thumbpick. When the camera pulls back moments later, you see what appears to be an early- 1960s Gibson GA-19RVT combo at the other end of her white cable.

Following the second chorus, Tharpe launches into a jaw dropping solo that begins with a double-stop and then leads into a series of seething, impeccably timed chromatic runs, a wild bend, and a series of sliding doublestops that bristle with energy, vocal-like phrasing, and a raw, powerful tone that would’ve given Chuck Berry a complex. At one point, she slams a chord and waves her arm back and forth in a move that’s simultaneously testifying and directing the chord’s repeatedly bent notes like a choir-director’s baton—it’s supreme showmanship that presages Keith Richards’ and Pete Townshend’s trademark “windmill” move. Through it all, Tharpe struts the stage, juts her head out in rock-star fashion, and generally commands undivided attention.

Tharpe’s guitar work during her performance of “Up Above My Head” on the same television show is slightly less distorted, but the performance is no less rocking. Note how she delays the beginning of her solo until part of the verse has gone by, then comes in confidently at exactly the right spot. Though Tharpe’s sound was primal and pure in its appeal, her approach was not primitive (she also played piano and was well schooled in music). At the beginning of the solo on this rendition, she effortlessly—and in perfect time—slides into chords up nearly the full length of the neck. She then hollers, “Let’s do that again,” upping the ante by sliding into single notes up near the end of the fretboard. For the G chord in the middle of the verse (the V chord in the key of C), she pounds the G string, bending it back and forth between the 9 and the minor 3rd. Like Wes Montgomery, she increases the excitement by switching from single notes back into chords. She finishes off with the classic Chuck Berry-style lick—alternating between slides up to a C# on the G string and fingering the same note on the B string.

In addition to Tharpe’s complete command of song via voice and instrument, as well as the passion she radiated from her body and soul, her rhythm guitar playing and solos (as evidenced by the aforementioned performances) weren’t merely great “for the time” or “for a woman”—they’re masterpieces of the ages that are worth studying as exemplars of tone, phrasing, fervor, and showmanship.

Make a Joyful Noise

By Jason Shadrick

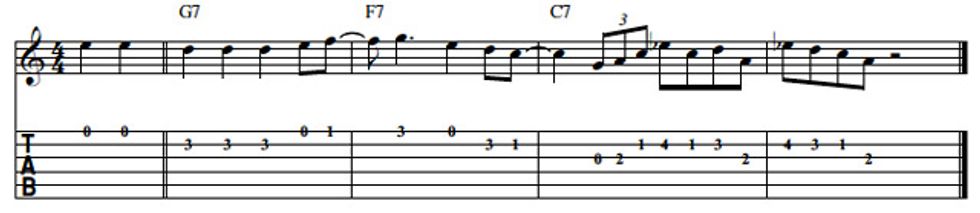

Figure 1

This is a typical intro that Sister Rosetta Tharpe would play to kick off a gospel tune in the key of C. Check out the cool use of the 9 (G) over the F7 chord in the second measure. During the last two measures, Tharpe creates a bluesy sound by using the b3rd (Eb) over the C7 chord. The sound of the 3 of C7 (E) and the Eb, creates a nice, tension-filled rub.

Figure 2

A common element Tharpe’s style was the use of open strings. Here, we begin with an open-string phrase that wouldn’t sound out of place in a Freddie King tune. Make sure to give the D on beat 3 a nice quarter-step bend. In the second measure, there are some ferocious triple stops and then the lick ends with some open string pull offs that are based out of the E blues scale (E–G–A–Bb–B–D).