Learn how to improvise your rhythm guitar parts and make your blues progressions more interesting.

Chops: Intermediate

Theory: Intermediate

Lesson Overview:

• Understand how to use guide tones to create chord voicings.

• Learn rhythm guitar techniques in the style of Robben Ford, Joe Pass, and Kirk Fletcher.

• Use voice-leading to develop a more fluid sound.

Click here to download a printable PDF of this lesson's notation.

A few months ago, I wrote a lesson about the importance of understanding the difference between various minor blues progressions [ Beyond Blues: Playing the “Right” Minor Blues Changes]. This is especially crucial when you want to sound your best at a jam session. After exploring Danny Gatton’s playing for the last two months, I thought it would be good to revisit blues progressions and look at some chord changes we can employ to break out of our tried-and-tested I-IV-V pattern.

You’re probably used to playing a 12-bar blues progression that looks something like this:

I-IV-I-I IV-IV-I-I V-IV-I-V

And while this is a perfectly acceptable way to play a blues, you’d expect a few more harmonic twists within a jazz-influenced progression. I’m not saying one progression is superior to another in any way—they’re just different. When you have options, you’re able to support a soloist if they start playing a few more jazz licks. Also if you’re the soloist, you’ll be able to pick up on the chords you’re playing over and adapt accordingly when you know how these alternative progressions work.

The main difference in our new progression will be the inclusion of a II-V-I cadence where you’d normally expect to find a V and IV. Let’s take a closer look.

The first seven measures function as normal (though for the sake of interest, I’ve included the “quick change” to the IV chord in the second measure), but after returning to the I chord in measure seven, we’re going to move down to a VI chord. I’ve made this a dominant chord instead of the diatonic minor chord because this chord can function as a dominant chord as it’s moving up a fourth from F# to B. It’s as if we have a V-I in the key of B.

This cycle continues, moving from F# to B, then from B to E, and then back to our “home” of A. You may remember us covering this common cycle almost a year ago (Beyond Blues: 12 Keys, Five Shapes, and the Blues). This common chord movement is perfect for a jazz player because it adds a bit of interest and gives us something more challenging to play over. So instead of I-I-V-IV-I, we have I-VI-II-V-I—a huge departure from where we started.

We follow this pattern in the turnaround with a “quick” I-VI-II-V (two chords per measure). Again, this gives us something a little more challenging to solo over. The trusty minor pentatonic scale won’t save us here!

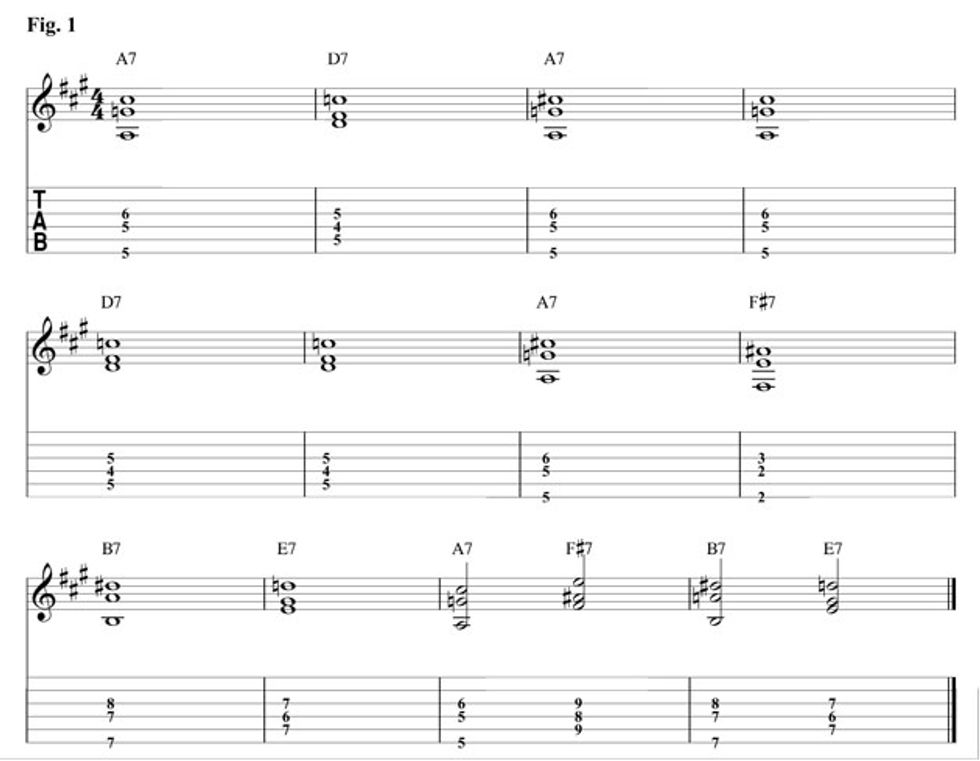

For our first example (Fig. 1), I’ve outlined these basic changes using simple three-note voicings. Each voicing consists of a bass note and the chord’s guide tones (the 3 and b7). These little voicings are a great way to introduce yourself to jazz-inspired rhythm guitar, and if you really want to take things up a level, try playing the same thing but omitting the bass notes. Playing just the guide tones is a great way to get into more authentic jazz comping, and it’s a perfect way to compliment the band when there’s a bassist. After all, it’s his job to play the root notes, so why get in his way?

In Fig. 2 I’ve tried to bring that last exercise to life with some syncopated rhythms and “four-to-the-floor” stabs. I’ve also tried to include a couple of extra little tricks that might help this progression gel a bit more.

The first trick was something I heard a lot from players like Joe Pass and Danny Gatton when I was learning about blues harmony. It happens in the third measure where I shift from the A7 to a Bb7 and then back to my A7. Rather than sit on the same chord, this shift creates a little more harmonic interest.

Next up, in measures seven and eight, where you’d expect to jump from A7 to F#7, I take my A7 voicing and move it down chromatically to F#7. This is a very common chord movement and you’ll often hear it in the blues improvisations of such chordal masters as Joe Pass.

The second trick lies in the second ending. Instead of the typical I-VI-II-V, I’ve employed tritone substitutions for smoother voice-leading. I took the A7 chord, shifted it up three frets to C7, then down a half-step to B7, then another half-step to Bb7. You’ll notice the two notes on top of each chord—our guide tones—actually remain the same as before, so it still sounds like a turnaround.

In our final example (Fig. 3), I’ve thrown everything together but have tried to make things a little more musical by using some of the organ comping ideas we’ve talked about in the past. I’ve omitted the quick change here and opted instead to use a nice little Robben Ford-style idea (I pinched this from the incredible Kirk Fletcher). From our organ-inspired comping (triads over bass notes), we then shift up to G13, voiced higher on the neck. From there, we move up chromatically to our home of A with an A13 chord.

For the IV chord (D9), I approach it chromatically from a half-step above with a rootless Eb9 voicing. Another way you can think of this is a m7b5 chord that’s built on the 3 of the dominant chord—in this case, Eb9. I then got a little “Joe Pass” with things and shifted up to a higher voicing that I treated in a more chord-melody style. Although each chord is a D7 sound, we have the D-E-D-C-A melody riding on top of the chords, and this is really pleasant on the ear.

The chromatic walk-down from the I chord to the VI chord is yet another bit I’ve lifted from Joe Pass. I’m using a common 13 chord shape and simple alternating chord stabs with melodic phrases focused on the root and 13. I then move up to the B7 chord and imitate the organ idea we began with before I finally shift to an E7#9 in place of our E7 chord. This one sounds great with an open E string.

For the final turnaround, I’ve taken the idea from our previous example’s second ending and concluded with a spacey A13 chord—something you’re likely to hear from fusion master Scott Henderson. I think it’s important to take advantage of tricks like these ... shifting a chord up and down is a lot easier on the brain than thinking A7, F#7#5#11, B9, E7#5#11, A13. Remember, we want to be able to improvise rhythm guitar like this and have fun with it. To do this, your ear has to be free to make music and not be bogged down with complex music theory that’s reminiscent of rocket science!