One of the most beloved (and humble) guitarists alive opens up about capturing the humanity in music without effects, improvising off of himself, and finding someone who would push him in the studio for the first time in years.

It was 27 years ago when Guns N’ Roses’ Appetite for Destruction hit the scene and a young Saul Hudson, soon to be known simply as Slash, relit the Les Paul fire during a time that other guitarists were wielding super strats and wearing spandex. Today Slash remains as popular as any guitarist (living … or maybe ever) and is one of the few who emerged from the ’80s unscathed by the musical canon of that era: glitz, glamour, and glorified shred. While many of his peers have disappeared in the rearview mirror, Slash is still making relevant rock three decades later.

When GNR disbanded in the mid ’90s, the top-hatted, transplanted Englishman with a mop of curls and a side-mouth smoke went on his own with Slash’s Snakepit. Then in 2002 he formed the supergroup Velvet Revolver with ex-GNR bassist Duff McKagan and drummer Matt Sorum, guitarist Dave Kushner, and vocalist Scott Weiland. Slash’s larger-than-life guitar talent and the music he made with GNR overshadows these later ventures, but he’s been making music ever since and remains arguably the most career-successful ex-GNR member.

With his current band, the Conspirators—Myles Kennedy, Brent Fitz, Todd Kerns, and Frank Sidoris—it appears Slash has found something he’s been looking for: a band that ignites together. “It almost sounds weird. Because you play around a lot, and you get known for playing with a lot of people,” Slash says. “You throw some people together temporarily—that was the original premise—guys who I didn’t know. And there was this amazing chemistry that happened, and when I tell people that, they’re like ‘yeah, yeah, yeah whatever.’”

This chemistry comes through on the group’s new album, World on Fire. With its cohesive sound, this naturally flowing collection of 18 barnburners provides a foundation for Slash’s extraterrestrial, high-flying tones and extensive soloing. It should come as no surprise that guitar plays a dominant role here: It has been at the forefront of Slash’s life since he first heard Aerosmith’s Rocks at age 14. How apt that Slash and his Conspirators just kicked off their release tour with Aerosmith.

When it comes to recording, the M.O. stays simple for Slash: commit live jamming to tape. Another crucial element was to collaborate with someone who knew guitar: Slash picked Michael “Elvis” Baskette to produce World on Fire because from the get-go, Baskette had the vocabulary to have a conversation about tone. “He was really, really passionate about guitar sounds, so that was it. I said, ‘You’re on!’”

Though World on Fire is the second effort from this lineup, Slash and the Conspirators are just getting started. “There’s really sort of a thing happening with these guys that’s developed over the last four years—it started with a spark and it’s really settling into something.”

How do you approach making rock ’n’ roll? How do you keep it fresh, and how do you keep evolving?

That’s really something that the listener has to come to a realization of. I can’t say that I purposely set out to do this and this and this, so it’s going to be modern. The approach I use is basically the same, I’ve altered it a few times over the years for certain situations, but I like to work quick. I don’t like to noodle around in the studio—it does not fascinate me. Playing in a room as a band is first and foremost the only way to do any kind of proper rock ’n’ roll recording. I’ve always found that playing live to tape has worked. I did a couple of Velvet Revolver records with Pro Tools, and the first one, which was a pretty popular record, has a tendency to sound very linear, which is what a lot of new rock bands sound like. There’s no dynamics because people sit there and tweak everything to line up. And they don’t realize it’s taking the actual energy and humanity out of the recording. People who listen to it don’t know what it is, but there’s something they’re not getting.

When we did that with Velvet Revolver it was ’cuz I sorta didn’t know any better. I witnessed that happening in the middle of the night. I’d left the studio and then came back to get my keys or something and found the engineer just tweaking everything. I was like, “What are you doing?” That was the first time I witnessed this in real time. Since then, I’ve been like, “No, I don’t want to do it that way.” So I stick to just recording as a band.

On our first record, Apocalyptic Love, the band was really developing, so I just recorded completely live to tape, no overdubs or any of that stuff. It was cool and we achieved it, and I got to see how good the band really was. This time around, I went back to recording live and doing my guitar in the control room and making sure it sounded right. I find that’s the best way to do it. If anything sounds fresh, it’s mostly from not trying to be retro.

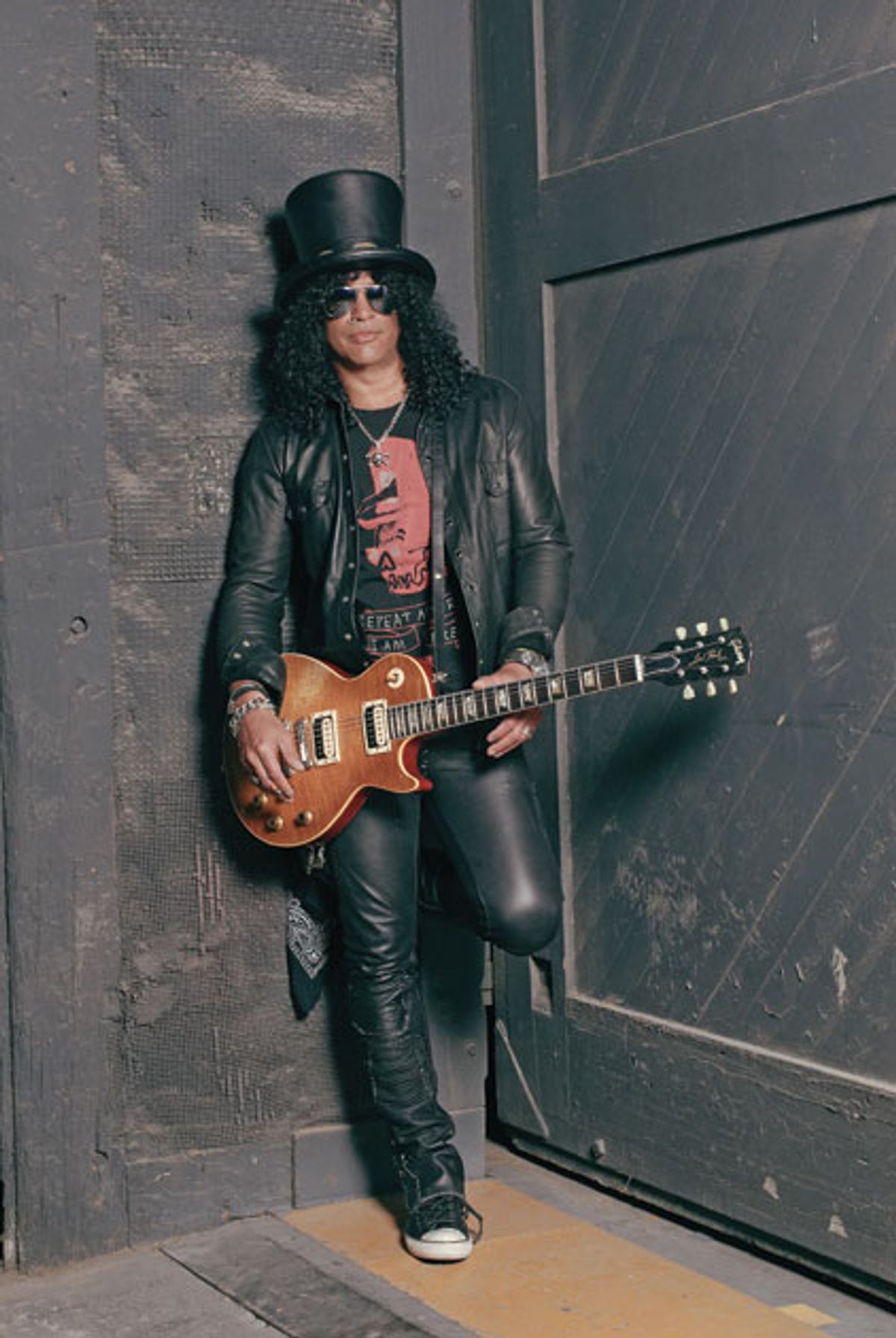

Slash gets into primo stance with his Les Paul while rocking The Fillmore in Detroit on September 22, 2012.

Photo by Ken Settle.

You said recently in one of the Ernie Ball Real to Reel episodes that the studio is intimidating. How do you get in the zone?

Yeah, the studio is a weird place. I enjoy being in the studio really because it’s an opportunity to bring whatever it is that you’ve been jamming on to some sort of recorded fruition. But trying to get what you want in the studio and working with certain people is really sort of a crapshoot.

As soon as the red light’s on, I tend to get inhibited, so I don’t play the same way I would at rehearsal. It means you’re overthinking it and you have to try to get past that, which takes a conscious effort. It’s hard, so for me to actually find my comfort zone in the studio, and really play from that place where I would go in a live situation, it’s just something that either happens or it doesn’t, ya know?

It seems like you and producer Michael “Elvis” Baskette had a real synergy and he pushed you in the studio.

Let me tell you something about Mike. Last October when we first started the whole writing process, all the way through the holiday, I realized I didn’t have a producer. Eric Valentine, who’s awesome, was busy doing something else and that didn’t seem like it was going to happen in the timeframe I was trying to do it in.

There were no new records I was excited about that made me go, “I want to work with this guy.” But Alter Bridge had a new record and I thought the bass and drums on it were fucking amazing. I talked to Myles [Kennedy] about it and he said, “I’ve been working with [Baskette] for a while.” But Myles has never pushed Mike on me, and he wouldn’t give me anything to go on. Myles just said, “You’ve got to call him.”

Slash's Gear

Guitars

“Appetite” Les Paul ’59 replica (built by

Kris Derrig)

Gibson 1957 Les Paul Goldtop Reissue

Gibson Slash Appetite Les Paul

Gibson Les Paul Junior

Gibson Melody Maker

Gibson Joe Perry 1959 Les Paul (Seymour Duncan JB humbuckers)

Gibson Les Paul 12-string

Gibson ES-175

Gibson ES-135 (owned by producer Michael Baskette)

Amps

Marshall JCM800

Marshall SL5 signature combo

Marshall AFD100 signature head

Marshall cabs

Effects (live)

Dunlop SC95 Slash Cry Baby Classic Wah

MXR SF01 Slash Octave Fuzz

Dunlop HT1 Heil Talkbox

Whirlwind Selector A/B box (for Heil HT1)

Boss DD-3 Digital Delay

MXR Analog Chorus

MXR Stereo Chorus

MXR Stereo Tremolo

MXR Boost/Line Driver

MXR Phase 90

MXR Smart Gate

Boss TU-2 Tuner

Dunlop DCR2SR Cry Baby Rack Module

Shure UR4D Wireless

Ebtech HE-8 Hum Eliminator

Whirlwind MultiSelector rackmount switcher

Strings and Picks

Ernie Ball Power Slinky (.011-.048)

Dunlop Tortex 1.14 mm

So I called Mike and we had a great conversation because he was a tape engineer at NRG [Recording Studios] back in the day.

He has altered his style to adapt to the modern

way people are recording, but he’s really a tape engineer. So that helped. And then we had a conversation about guitars. I’m really sensitive at this point about guitar sounds because I’ve found that most of the people I’ve worked with don’t really know enough—or want to know enough—about achieving a great guitar sound without using a bunch of stuff. That’s the way everybody’s used to doing it. It’s like, we’ll just use plug-ins and some Line 6 ... all the shit I would never use.

And so when it comes to just miking an amp and getting a great sound out of it, they’re like a deer in headlights. It becomes a situation where I have to tell them what to do, and that doesn’t really work because I don’t know that much [laughs]. I’m not a great engineer, obviously because I don’t love the studio that much. Like

I said, it doesn’t fascinate me. It’s just not my thing.

We had a really great time with [Baskette] and he’s a really hard worker, which is great ’cuz

I’m a hard worker—everybody in the band is really fucking focused.

So how did you approach the guitar sounds with him?

We went to his studio in Orlando. All my stuff is pretty spontaneous in the sense that whatever

I was doing in rehearsal, that first thing that fits, melodic-wise and whatever, I tend to just stick with ’cuz that’s my gut feeling. Usually the first few takes is what’s going to be on a record, but he pushed me past that, to the point where I was improvising off myself. Whatever it was I had, he kept having me play until I left that behind and started doing other things with it. And it was really cool because no one had had the patience or wherewithal to do that with me, or get me to listen to them either. After a couple of takes you lose the spontaneity, but if you keep going, the spontaneity comes back because you’re not doing what you thought you were going to do.

That was probably exciting for you.

Oh yeah, man, I had a blast! As far as guitar sounds are concerned, I just loved that he would go above and beyond the call of duty—even to the point where I was fine and he’d go, “No, no. We’re going to keep going.”

What guitars were you working with in the studio?

I only took eight guitars down there, stuff that I knew I was going to use: a few Les Pauls, an Explorer, and a 12-string. I had a vintage Junior and a reissue that worked out for some stuff, but the reissue sounded better. I didn’t have a lot of variations on a basic sound. When I started doing other tones, I wanted to get away from the stock Les Paul sounds I use so it didn’t sound like Judas Priest. Mike had an ES-135 I checked out and it sounded amazing. Within a couple days I learned the next step up from that was the ES-175, and Gibson sent one over and that sounded fucking amazing. Those were the main speaker left/stage right guitars I was using.

So did you play all the guitar parts on the album or did Myles play some?

I played all of the guitars, speaker left and speaker right. He played the other guitar parts on the Apocalyptic Love record—he’s a phenomenal guitar player. I mean he was actually a guitar teacher, let’s put it that way. So he knows stuff. I don’t know what I’m doing—he knows what he’s doing. Technically I don’t know a lot, you’d be surprised. He knows all kinds of scales and picking techniques, and every so often I’ll go, “What was that?” And he’ll show it to me, I’ll incorporate it in something I do for a minute, and then I’ll never use it again [laughs].

When we did the Apocalyptic Love record, he was on the road with Alter Bridge, so when we started recording he came in at the last minute and had to learn all the songs on guitar really fast. That cut into his writing and vocals, and so he was very uncomfortable with all of that. So on this one he said, “You play guitar and let me just deal with vocals.” So I said, “Cool—more for me!”

Slash grips his Kris Derrig Les Paul replica (right), which was the inspiration for his signature Gibson Appetite Les Paul model (left). Photo by Neil Zlozower.

Slash’s Holy Grail Guitar

Asked if he had to choose one guitar to play for the rest of his life, Slash answered without hesitation that it would be his Kris Derrig Appetite Les Paul, his go-to guitar since 1986. He’s used it on every recording since Appetite for Destruction.

“We’re like an old married couple—she’s very temperamental,” he says. “You have to work to keep her in tune and I’ve had to replace little parts, but overall that’s where I can easily get my sound.”

So what is it about this machine? “I can do whatever it is I do on whatever Les Paul, but if I A/B that guitar with any other guitar, it has its own personality.”

He stopped taking his girl on the road in 1988, but she’s still his No. 1 studio beast. For touring, he has his Gibson AFD Les Paul Standards. “I beat the shit out of my guitars,” he says of his signature model. “It’s the same guitar but new, and I can beat them up.”

There is some controversy surrounding the history of this Derrig LP replica [see “The Legend of Slash’s Appetite for Destruction Les Paul,” Premier Guitar, October 2010], but Slash maintains that it really is his one true love.

Tell us about your songwriting process.

I write in the moment and never look at anything through a past perspective. I write when we’re on the road, in the dressing room, or I’m in my hotel room, and I keep my phone close by and I just play all day. And if I stumble across anything that I think is cool, I’ll keep playing it until I develop it and record it onto my phone—it could be 30 seconds or two minutes or whatever. By the end of the tour, I’ve amassed ideas. After the tour is done I decompress for a few weeks, and then I’m itching to go back to work and listen to all those ideas.

How easily do those parts come to you?

The thing is, they come easy because you’re not trying. That’s the big thing for me. Because if I sit down and focus on trying to write something, then it becomes really difficult.I wouldn’t be able to write in the studio. It might just magically happen, but nine times out of 10 it won’t. Then you just sit there and start beating yourself up for not being able to create in the moment.

A young Saul “Slash” Hudson plays one of his first guitars, a late-’70s B.C. Rich Mockingbird, during a performance at L.A.’s Fairfax High School in 1982. Photo by Marc Cantor / Atlas Icons.

You’re known for your trademark sound. When you wail on a guitar, people know it’s you. Can you offer any advice for young players trying to find their voice?

Any passionate guitar player, a kid that’s going to pick it up and just loves the instrument and the way it sounds, even if they’re just starting out, they’re usually inspired by something, a handful of people, or a style. You just have to pursue that.

What turns you on about guitar?

The funny thing about it for me is I was raised in a guitar-laden environment and never knew it. I was turned on to rock ’n’ roll from the very get-go, because my dad and his brothers were all big rock fans and we were all living in England. All I heard was the Who, the Stones, the Kinks, the Yardbirds, and some Moody Blues in there. My dad said, “The most important part of the song is the guitar break.” I was surrounded by that.

Then I moved to the States and both of my parents were really big music people. I loved going to rehearsals and recording sessions of people that they were working with. Or going to gigs and that minute where people get up and pick up their instrument was a huge turn-on for me. The best part of the show was that—before the first song.

I always dug guitars but I didn’t aspire to be a guitar player. It wasn’t until I put a couple notes together that sounded like a blues lick, then it was like the heavens opened up, it was like “ahhhhhh.” I’ll never forget that moment. What I was looking for was the British guitar that turned me on all my life until that point. It was Aerosmith at first, that Rocks record of theirs really spoke to me and set me off in a certain direction. Simultaneously it was Jimmy Page, Eric Clapton, Billy Gibbons … anybody who had a personality in rock-style guitar playing—that’s what really turned me on and that’s the direction I went. And I never faltered from that, that’s why I never became Randy Rhoads or any of those guys, especially in the ’80s.

No, you’re Slash.

[Laughs.] But at the time I was the only guy that started doing that, everybody was on this sort of ’80s guitar pyrotechnics wave kinda thing. But I was still really dialed into Mick Taylor and Keith Richards and stuff like that.

YouTube It

Slash closes out a show with his favorite song to play live, “Paradise City,” with Myles Kennedy and the Conspirators in 2011 as part of Slash’s solo live album Made In Stoke 24/7/11. It was recorded in Stoke-on-Trent, England, where Slash lived as a child.

Recorded at the House of Blues in Las Vegas, this full concert is from the Apocalyptic Love tour. Check out Slash’s doubleneck solo at 33:27 during “Civil War.”

If you were banned from using a Les Paul, what would you play?

If I couldn’t play a Les Paul, then I might pick up a Melody Maker or a Junior or something lighter like that with humbuckers, or a Telecaster with humbuckers in it. There’s definitely something about Les Pauls and humbuckers and that warm, heavy, midrangey sound that attracted me when I was first starting. My first guitar was a Memphis Les Paul copy, so I automatically went there. Then I went through a whole period of trial and error with Strats, B.C. Richs, Telecasters, and other odds and ends, and ended back at Les Pauls.

Did you play your Appetite Les Paul in the sessions for World on Fire?

Most everything panned over to the right speaker and in the middle is my [Kris] Derrig guitar, and I also used a goldtop ’57 reissue for that creamy stuff where it’s sustainy smooth where I turn the tone down.

Can you give us an example of where you’re playing the goldtop?

The guitar solo on the very end of “The Unholy” and also on “Battlefield.”

If your music had an odor, what would it smell like?

[Laughs.] That’s the most original question I’ve heard in the last 30 years. It would probably be like barbecue sauce or something. It couldn’t be fresh cut grass and it wouldn’t be fresh flowers or raw meat or anything. It would have to be something spicy and something sweet but

something funky …

If you were stuck on a desert island and had to choose between your hat and your guitar, which would you choose? Oh, it’d be my guitar—come on!