This guitar-driven duo channels Iron Maiden, Coltrane, and ’70s German techno to make a different kind of heavy.

Southern California guitar-and-drum duo, the Mattson 2, is not another White Stripes/Black Keys knockoff. Not even close. Their music is modal, spacious, hypnotic, instrumental, and oozes the laid-back, endless summer vibe of those beach towns south of L.A. The Mattson 2 creates music to get lost in, and the group’s new album, Agar, is a potpourri of sonic colors and trance-inducing grooves.

And what’s more, the Mattson 2’s music exudes the duo’s telepathic, otherworldly, connection. Jared (guitar) and Jonathan (drums) Mattson are identical twins. That inexplicable-mind-reading-twin-thing is essential to their sound. The mysterious bond informs their sense of groove and phrasing, and allows them to express their intrinsic, yet subtle, idiosyncrasies.

Jared started playing guitar in the 7th grade. “We had a guitar in our house from our uncle. Our mom didn’t want us home with our skate-rat friends getting into trouble, so she signed us up for guitar lessons after school.” It blossomed from there. “The music I was listening to at the time was super guitar heavy—bands like Iron Maiden and Metallica—so I just started loving the guitar.” His brother didn’t click with the guitar in the same way, but he did with the drums. “When Jonathan started playing the drums it was insane,” says Jared. “He had real natural ability.”

The lack of a permanent bass player forced the twins to incorporate live loops into their music early on. Jared looped bass lines and rhythm guitar parts, and those loops created a need for more sonic options—and hence more effects—and ultimately more (and more) gear.

The Mattson twins earned bachelor’s degrees in music from the University of California at San Diego, and then went to UC Irvine for master’s degrees in Integrated Composition, Improvisation, and Technology (ICIT). The latter experience was transformative. “The improvisation focus of UC Irvine helped us in our compositional method,” says Jared. “We realized that there is a really interesting thing you can do musically by mixing unfamiliar sounds with familiar sounds. I think our studies brought us to that realization.”

Agar, the Mattson 2’s fourth album, does just that. Combining natural guitar tones with loops, luscious soundscapes, pedal-steel drones (played by friend and collaborator Farmer Dave Scher), the album features unorthodox song forms and countless sonic surprises. We caught up with Jared Mattson on the heels of a massive tour the twins had just finished to support Agar, and asked him to describe his guitars, loops, outrageous effects, and innovative approach to recording.

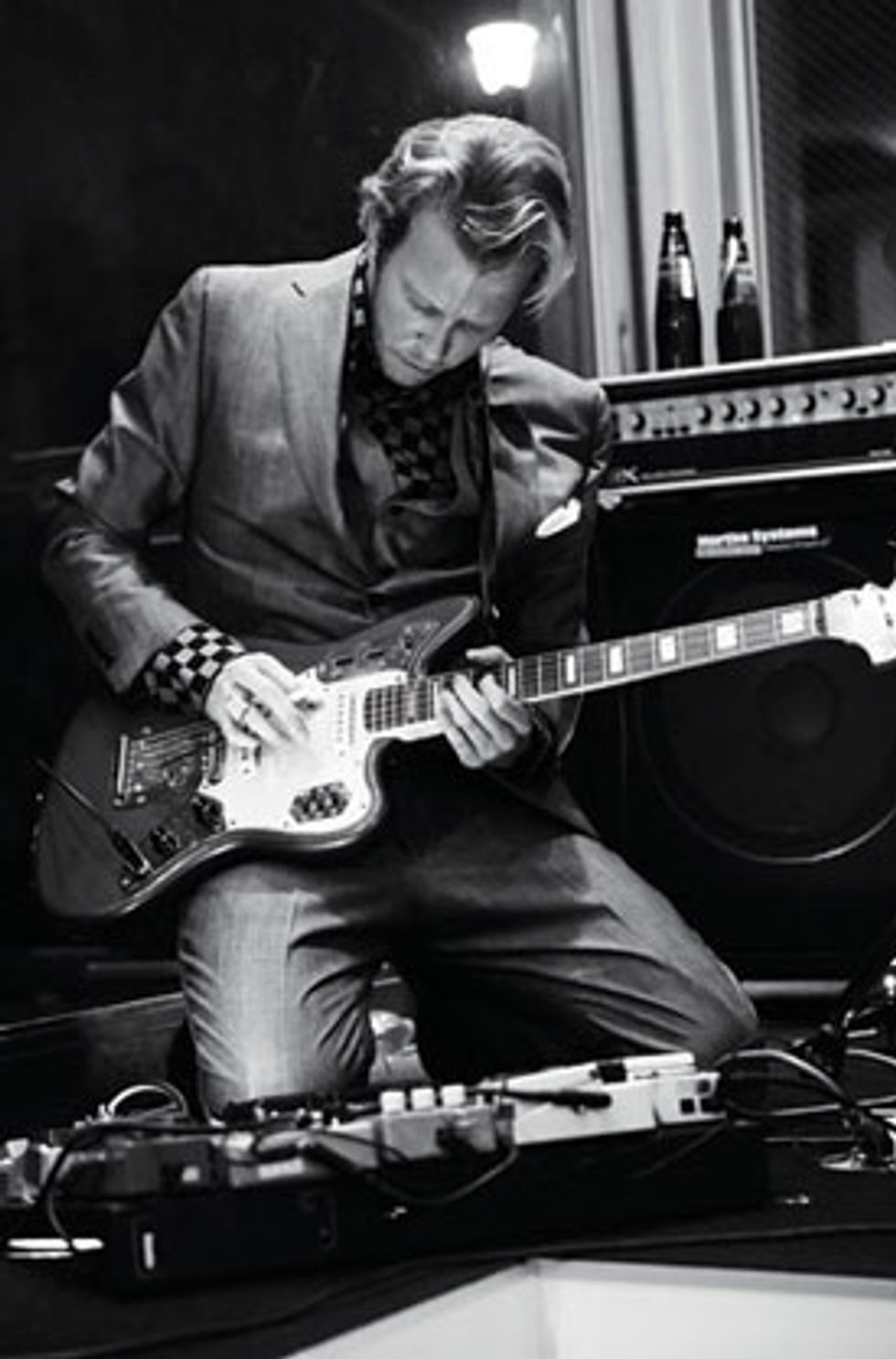

Photo by Yuichi Yoshida.

You do a lot of looping and improvising. Do you find live looping constraining—does it feel like you’re playing to a click track?

That’s an interesting word—constraint—because I think in all good music there is constraint. Constraint breathes the most interesting music. Our initial constraint was that every bass player we had when we were around 17 or 18 kept leaving the band. Not because they didn’t like the music, I hope, but mainly because they pursued other opportunities and moved away from the area. When that happened we had to figure out a way to create a full sound with only two people. I didn’t want to sacrifice my melodic sense or my soloistic approach with having to play chords and solos at the same time. So when I saw my friend [skate legend and guitarist] Ray Barbee play with a looper pedal, I thought, “Wow, that’s what I need to do.”

But we use loops in a different way than most people do. I create all my loops live with no click track and we work with our own natural, internal rhythm. When you play with the loop there are a lot of imperfections rhythmically, because it’s never going to be in perfect rhythm. As humans, we’re not in perfect rhythm. But I think what really makes that work for us is our twin connection. Being identical twins allows us to play with those imperfections and respond to those imperfections in a natural way.

I also like to loop a lot of overdubs, and I make sure each overdub is not a repeated sound. For example, if I start the loop with a bass line, maybe I’ll support that bass line with a rhythm guitar playing that same line with a phaser on, or something subtle so it adds texture to the bass groove. After that I’ll add some sustaining chords with a tremolo pedal, or I’ll find one note from the chord and let it ring out, or I’ll do a volume swell with the fuzz pedal. So every sound has its own distinct identity, and that comes from my desire to turn the guitar into an orchestra.

When you play the same song night after night, do you lay down those loops fresh every time? You don’t have banks of pre-programmed loops?

Most of it is fresh. But I don’t see any harm in using prerecorded stuff either. I actually really enjoy it. While I was at UC Irvine, one of my professors, Michael Dessen, offered something really interesting. He said, “What if you create a loop and it doesn’t sound good?” I thought, “Well, that happens, right?” But he suggested contrasting view. The excitement of creating a live loop is cool, but what happens if you spend three days creating a very perfect, honed, beautiful loop that’s meant to be there as support for the live performance? So I go both ways. I’ll spend a lot of time orchestrating and perfecting a prerecorded loop for live performance, and I also see the value in spontaneously recording something in real time and playing it back in real time.

What looper pedal do you use?

My favorite one is the Boss RC-20XL Loop Station. I also pair it with the Boss RC-30, which I’m not a huge fan of, but it does the trick.

Mattson’s main guitars are a candy apple red 50th Anniversary Fender Jaguar and a Gretsch White Falcon. Both instruments are stock, but Mattson loves the “juicy” pickups on the Jaguar.

Isn’t that just an updated version of the 20?

Yeah. But I love the 20 because there is a seamless transition between the banks. If you start on the first bank and then go to the second bank, there’ll be a perfect bleed from one to the other. But with the Roland 30, if you go from bank 1 to bank 2, there’ll be like a 10 millisecond separation between the two, which is not good for a live performance. But that brings us back to the concept of constraints—you learn how to work with these limitations in a creative way.

You also use Tonebutcher effects. What can you tell us about them?

Tonebutcher is a small operation out of Costa Mesa, California. Todd Rogers and Richard Lingenberg create boutique, one-of-a-kind pedals. They like their pedals to do very surprising, uncanny—sometimes uncontrollable—things. I have one of their fuzz pedals [the Pocketpus], and you can never control exactly what sound you’re going to get from it.

Meaning you can’t get the same sound twice?

Exactly. And these pedals are smaller than the palm of your hand. Tonebutcher pedals have blank knobs—you don’t know what each knob does—so as the artist, you have to experiment with the sounds yourself, which is pretty rad. They just give you the pedal with two knobs on it and you have to discover what they’re for [laughs].

What if you really love a sound and you want to duplicate it night after night?

I try to. Once you plug the pedal in, it becomes almost like its own instrument. You can recognize certain sounds that you’re able to get from it. I make little marks on the knobs where I like the sound of that combination of knobs. You can do that and it will be right on—sometimes. It’s also good as an improvisation tool to just do a freakout session on.

Jared Mattson's Gear

Guitars

Fender 50th Anniversary Jaguar

Fender Jaguar Special

Telestar guitar/bass doubleneck

Gretsch White Falcon

Gibson ES-335

Amps

Fender Deluxe Reverb

1953 Gibson Tremolo

Acoustic 1x15 combo

Fender Bassman combo

Effects

Boss TU-2 Tuner

Boss DD-3 Digital Delay

Boss RC-20XL Loop Station

Boss RC-30 Loop Station

MXR Phase 90

Behringer Ultra Chorus

Electro-Harmonix Micro POG

Ibanez TS9 Tube Screamer

Tonebutcher Pocketpus

Tonebutcher Adverb

Strings and Picks

Ernie Ball or D’Addario .011 set

Dunlop Tortex .73 mm picks

But the Tonebutcher pedal I like the most is called the Adverb. It’s more than just a reverb pedal. It has 24 different kinds of reverb on it, it has weird phasers on it, it has a chorus, and it has some automatic delays. You can’t control the delay feedback—it just has these presets, and they’re really interesting delays, too.

And all that fits in your palm?

Oh yeah. If I didn’t need to use the loop pedal, probably all I would need is that pedal. A fuzz pedal and then the Adverb.

You use fuzz very subtly—it doesn’t sound like there’s much of it on Agar.

I love the saturation that [jazz guitarist] Grant Green got on his recordings. He had more of that tube-driven gain, just more of a natural graininess to it, like a tape-saturation type of thing. That’s what my approach is, like a really subtle amount of Ibanez Tube Screamer. I turn the gain totally off and I turn the saturation up quite a bit.

Do you practice pedals the same way you’d practice scales or chords?

Not right now, because I have my sounds styled, but there was a time when I was at UC Irvine where every day for several years I’d experiment with different pedal sounds. It took about two years to get where I’m at now, effects-wise, so I think I can take a break from practicing pedals a little bit.

Do you approach pedals the way you would approach another instrument?

Totally. I think that comes from my love of the band the Cocteau Twins. Robin Guthrie is one of my favorites. He classified himself less as a guitar player and more as a guy who uses the guitar as a means to channel effects. I’m not so much that way, but I do like that approach where you focus on the huge sound using effects, as opposed to just the natural sound of the guitar.

And you incorporate them into your compositional process as well?

Totally. If you listen closely to all the songs on Agar, it sounds like there are less effects happening than on Feeling Hands [Mattson 2’s previous album], where there are a lot of effects.

But we recorded everything live for Agar. Imagine 10 different tracks, with 10 different effects, but they’re all coming through one amplifier and it’s being recorded by one microphone. I got that approach from Brian Eno—his more ’70s stuff. He would have all this information looping on his tape machine, maybe 20 different tracks at once, but he would record that with just one mic. So I like that sound, too. Using the studio as a means to get sounds you could never get live.

Jared Mattson is no stranger to the rabbit hole of guitar sounds. “It took about two years to get where I’m at now, effects-wise, so I think I can take a break from practicing pedals a little bit.”

So you don’t record the different loops on different channels in order to mix them later. Everything is coming out of one speaker and what you hear is what you get.

Exactly—it’s the same approach that Les Paul used. Whatever he did in that take was married to the tape and could not be mixed afterwards. Our approach wasn’t as severe as that, but we recorded everything live with one mic and there’s no separation between the different guitar tracks and different effects. That was the first time we tried that, and I really like the sound of it. It’s more true to what we are as Mattson 2. You can hear the telepathic connection we have sonically.

Someone called it twin-chorionicity.

Yeah, twin-chorionicity, that is what the engineer [John X Volaitis] called it. I like that, too [laughs].

Did you do more live loop overdubbing on this album than on your previous ones?

Yeah. I’m really happy with our other albums, but the reason I like Agar is because everything was live. It was documenting us as a band at this current state in our career. The other albums were really cool, but the same kind of magic doesn’t happen when you’re separately tracking in different rooms in a studio. The other albums were more that way. In hindsight, looking back at it, that wasn’t really a kind of twin-connection way to approach recording. We recorded the underlying rhythm tracks with drums and then Jonathan just sat out for two days while I did all the overdubs. Tracking live was way more collective and way more based on our twin connection.

Who were some of your influences growing up?

The two records that got us into jazz are really the same records that got everyone else into jazz, [Miles Davis’] Kind of Blue and [John Coltrane’s] Giant Steps. They’re hallmark albums, but they really do have an effect on people. And at a young age—in high school—they were a huge deal for us. Before that, Jonathan and I were super into Metallica and Iron Maiden. That really helped us develop a sensitivity toward heavy, guitar-focused music. I think that’s why we write the music we write. That’s why we like to be melodic, too. There’s a lot of heaviness but there’s also a lot of melody, which I’m super into.

Were you into Coltrane’s modal period as well?

Yeah, Coltrane’s “India” was a big influence on Agar. I love the freedom of just playing on one note, one chord, and one bass line because it frees you up melodically. It’s hard to get in a trance listening to Charlie Parker—it’s very pleasurable and it’s lovely to listen to—but it’s hard to get in a trance. It’s easier to get in a trance with something that’s very constant and repetitive. I’m more into zoning-out, in-the-moment types of music, so I think a drone and the modal stuff helps with that.

YouTube It

Jared Mattson plays his 1967 Telestar doubleneck on “Pleasure Point” from Mattson 2’s 2011 album, Feeling Hands.

In this superb live performance, the duo’s jazz influences ring out loud and clear, and we see how Jared layers multiple loops to create a guitar orchestra onstage.

Techno has a similar trance-inducing energy. Do you listen to any of that?

Actually I don’t really listen to techno—I don’t hate it or anything—I’ve just never gotten around to it. I do like early German techno from the ’70s. There’s a composer named Manuel Göttsching, who I’m super into. His music was way less from a club standpoint and more from a composer standpoint. He came to his record label with the idea of creating a 30-minute piece of music with only two chords. He came from that minimalist music, like Steve Reich.

Thank you. I totally agree [laughs]. I like surf music but I’ve never, ever tried to play it, and we never tried to sound like it. We appreciate that people have their own way of identifying with our music, but we’ve never consciously tried to make surf music. I think there are a lot of formulaic things in surf music that we’re associated with, like the strong melody and the grooving drums, but I don’t know ... maybe it’s because surf music is a form of instrumental music that’s really relatable to a lot of people. And I think that we make music that resonates with a lot of people. We don’t try to alienate our audience with highly experimental stuff. We like to make catchy melodies.

Jared’s Pedalboard

Jared’s Juicy Jaguar

Mattson’s main guitars are a candy apple red 50th anniversary Fender Jaguar and a Gretsch White Falcon. Both instruments are stock, and Mattson is thrilled with the sound of his Jaguar. “I just love the pickups on that,” he says. “They really respond well to effects. Someone at one of our shows described it best, ‘It just sounds like it’s sizzling.’ It’s pretty juicy. I can get it to sound like clean glass once in a while, too, if I add some reverb and chorus on it. It just has a lot of different characteristics.” He also likes the Jaguar’s tremolo arm. “I call it my paint brush,” he says. “And I don’t have any trouble staying in tune with that guitar.”

Mattson’s amps include a 1953 Gibson Tremolo and his main squeeze—a 13-year-old Fender Deluxe Reverb. “That’s just the best amp in the world,” he says. “It can do anything.” He splits his signal and sends his loops to a solid-state Acoustic bass amp with a 15" speaker. “I used to send all that stuff—all the loops and bass lines—through my Fender Bassman, which is a rad amp, but the speakers started blowing a lot. They had trouble holding all the information.”