John Jorgenson's instrumental album, Gifts from the Flood, features guitars that were rescued and restored after being submerged for days in river water, diesel fuel, and raw sewage. Here he cradles one of these instruments, a '61 SG Les Paul. "It was my first good guitar," he recalls. "I bought it with monthly payments when I was 15 or 16 years old."

On his epic triple-disc set, Divertuoso, the multi-instrumentalist dives deep into bluegrass, jazz manouche, hot-rod country, and instrumental rock.

In 2010, the city of Nashville was subjected to two days of torrential thunderstorms in what was one of the area's worst natural disasters on record. The Cumberland River crested at nearly 52 feet, covering the Grand Ole Opry stage with two feet of water. Those floodwaters also poured into Soundcheck, Music City's storage and rehearsal site for A-list musicians.

More than a few music professionals saw their instruments completely destroyed. John Jorgenson—the freakishly talented guitarist and multi-instrumentalist who has worked with everyone from Elton John to Bonnie Raitt to Bob Dylan—had many of his best pieces in storage during the flooding, and all of them were at least partially submerged. A musician's worst nightmare, to say the least.

But he was lucky.

Over the course of many months, Nashville's ace guitar tech Joe Glaser was able to carefully resuscitate nearly all of Jorgenson's gear that was damaged in the flood, including a quintet of classic Gibson solidbodies and the Telecaster he wielded in the Hellecasters and the Desert Rose Band.

Incredibly, Jorgenson found that the refreshed instruments sounded and played even better than they did before the great deluge. Just as water had seeped into the instruments, Jorgenson witnessed new compositions pouring out of them. And working at a feverish pace, he documented them on Gifts from the Flood, his new electric instrumental album.

Around the same time he completed the album, Jorgenson—a Gypsy jazz ambassador as well as one of the great country pickers—was putting the finishing touches on outings with his Hot Club and bluegrass ensembles. And rather than release the three albums consecutively, Jorgenson chose to bundle them in one massive package. Divertuoso, which includes Gifts from the Flood, The Returning, and From the Crow's Nest—40 tracks in all—might be one of the most ambitious guitar releases ever, by any player, in any style.

Speaking from his home in Ventura, California, Jorgenson told us about the metamorphoses his instruments underwent in the flooding, and about how he manages to work at such a high level across a range of idioms and instruments.

There's a staggering amount of music on Divertuoso. Did you intend from the beginning to release three different albums at the same time?

I didn't really set out to do all three at once. They started at different times with different agendas, but they came close to being finished around the same time, and I had the choice of putting them out individually or together, as a package. It felt like a risk to release so much music at once, but I was willing to take that risk to put myself out there. If I'd thought about doing the whole thing as one big project, I probably would've been too overwhelmed and not completed it. But being able to complete each album in its own time made it manageable, sort of like looking at the mountain from the other side.

The electric disc, Gifts from the Flood, is obviously a reference to the disaster that wreaked havoc on so many instruments, yours included. How did it feel to have that happen?

It felt devastating because, like most guitarists, I'm pretty much a gearhead. I've been lovingly collecting guitars as a player for my whole life. I was one of those kids who'd just pore over a Gibson catalog, wondering if I would ever have any of those guitars.

The flood happened when I was on tour in Germany. I found out that, first, the basement of my house flooded. That's where all my vintage amps were, and so that kind of freaked me out. At first, no one could help retrieve them, because the roads were all messed up. A couple of neighbors and some relatives were able to come a day later and pull everything out of the basement.

Then I got the news that my storage locker in Nashville also flooded. It was full of guitars and other instruments—some of my most favorite pieces. Some I'd had since I was a kid, like the '61 SG Les Paul I used on the opening track. It was my first good guitar, and I bought it with monthly payments when I was 15 or 16 years old. The locker was unreachable for a week. It was a strange feeling to know that I'd very likely lost most of my instruments. But I have to admit I was one of the lucky ones. I had good insurance that covered everything, and Joe Glaser went into my locker, took everything apart, and started to triage it as much as someone could at that point.

Through that process a number of instruments were saved, and once they were playable again, I actually appreciated them so much more the second time around. They ended up giving me so many songs. That's why there are some titles like “'64 SG Custom 3." That guitar gave me two other songs, but there was only so much I could fit on one album.

What was the extent of the damage?

Some of the guitars had to be taken apart and cleaned with a toothbrush to get the rust out of everything. But some had grown mold inside and needed more extensive work.

What was it like to receive the repaired instruments?

It was amazing because they were new and familiar at the same time.

It must have been interesting to see how different pieces fared. What did you learn?

I learned that Fender pickups don't fare as well as Gibsons, because a Gibson has a metal bottom piece and Fender has fiber. Fiber tends to take on the water and cause the coils to break. On the other hand, Gibsons have more holes in them for the water to get into the wood. Also, it seemed like the cheaper the finish, the better it withstood not just water, but the diesel fuel and sewage that came with it.

How did the revived guitars sound?

Some seem to sound better than before. I asked Joe about that, and he told me a number of people had said that same thing. He speculated that, for newer guitars, being waterlogged would artificially age the pickups due to the many small fractures in the coil windings. The pickups became imperfect in the flood, creating the sort of comb-filter effects that everyone loves so much in 40-year-old pickups.

Did your pickups survive the flood?

Most of them did. Joe was able to rewind a bunch of them, which was kind of amazing, considering the condition they were in after the flood. But the pickups in one or two guitars had to be replaced. That wasn't necessarily a bad thing. Before the flood, the '64 SG Custom had non-original humbuckers that I'd been meaning to replace, so I took the opportunity to find better pickups for it.

Vintage gear tends to have a certain aroma. What did your instruments smell like after the flood?

At first the smell was horrible—like I said, a combination of diesel fuel and sewage, not to mention mold. It was just awful to remove the back of a Marshall 4x12 and smell inside the cabinet. Luckily, those odors subsided once the gear was cleaned up, but the pieces didn't smell vintage anymore—that combination of cigarette smoke, sweat, and a little bit of mold in the old cases. They pretty much lost that.

The compositions on the disc are all titled after the guitars you played on them. Did the guitars inspire the pieces, and what was your compositional process like?

Each guitar would kind of push me in a certain direction. I normally don't write things down when working. If I can't remember it, then it's probably not a strong enough melody. But so many songs were coming out at the same time that I found a shorthand way of notating them—not through notation and not through tab, just little things to help me remember everything.

Strangely enough, even though the album is all electric, I wrote most of the pieces on guitars not plugged in. The acoustic properties of the electric guitars are what pushed the compositions. For example, on “'70 Les Paul Custom," the guitar has a kind of sweet sound in the high register way up the neck, acoustically speaking. And that sound informed the melody of the song.

As for the notation, I just wrote the chords down and sort of notated the lead notes in a rhythm and the frets underneath that. It wasn't even on a grid—just a little something to remind myself.

On “'64 SG Custom," the guitar has a beautifully singing tone. Is that how it originally sounded?

That was one of the guitars that sounded so much better after the flood. I mentioned that the electronics had to be changed, but also the fretboard started pulling off the neck. That's because the guitar had been in a trunk full of water. Some of the others were in more of a vault, where the guitars were in a standing position, and so the water subsided. But the ones that were in flat trunks retained the water, and, as a result, it damaged the guitars' glue. Anyway, when that SG came back to life it had this amazing feedback quality to it—it could sustain and feed back without being super-overdriven. You can hear that tone on the track.

Onstage at Nashville's City Winery, Jorgenson entrances the audience with his fiery Gypsy jazz licks. “I was asked to recreate two tracks for a film featuring Django Reinhardt called Head in the Clouds," he says. “It was great to actually get paid for something I would have done anyway, to transcribe and learn exactly what Django played." Photo by Andy Ellis

How did you come to work with Brad Paisley on “Sunburst Tele 2" and what was it like?

“Sunburst Tele 2" is probably the most country cut on there. That guitar wasn't under water but the amp, a 1964 Vox AC30, was submerged. Before the flood, Brad had told me that particular combo of guitar and amp—which I'd used on the Desert Rose Band's version of “Hello Trouble" from 1988—was his favorite guitar tone ever. It was unbelievable that the amp came through. All the screws and bolts were rusted, and even the speakers had gotten soaked.

John Jorgenson's Gear

On The Returning:

Guitars

• Altamira flamenco

• Gitane DG-300 John Jorgenson model

• 1942 Selmer oval-hole 14-fret

Other Fretted Instruments

• 1927 Gibson K-4 mandocello

• 1980 Gibson F-5L mandolin

• Matsikas custom bouzouki

Strings and Picks

• Savarez Argentine (.010–.046)

• D'Addario Gypsy Jazz (.010–.046)

• Wegen Fatone 5 mm and vintage tortoiseshell flatpicks

On From the Crow's Nest:

Guitar

• 2012 Blueridge BR260A

Mandolins

• 1980 Gibson F-5L

• 2010 Kentucky KM-1000

Strings, Picks, and Accessories

• John Pearse 700M Phosphor Bronze (.013–.056)

• John Pearse 80/20 Bronze mandolin set (.011–.039)

• Wegen Bigcity and vintage tortoiseshell flatpicks

• Shubb capos

On Gifts from the Flood:

Guitars

• 1957 Fender hardtail Stratocaster

• 1983 Fender Telecaster Custom

• Fender Jazzmaster

• Fender Paisley Telecaster

• Fender Custom Shop John Jorgenson Signature Telecaster

• 1960 Gibson J-160E

• 1960 Gibson Les Paul Junior

• 1960s Gibson Firebird (from components)

• 1961 Gibson SG Les Paul

• 1964 Gibson SG Custom

• 1970 Gibson Les Paul Custom

• 1966 Silvertone U-1

• Takamine JJ325SRC John Jorgenson Signature acoustic-electric

Other Instruments

• 1968 Coral Electric Sitar (by Danelectro)

• 1990 Atlansia Victoria Bass

• 1998 Fender Duck Dunn Precision Bass

• 1967 Fender Telecaster Bass

Amps

• 1966 Danelectro DS-50 through a Vox Buckingham cabinet

• 1965 Marshall JTM45 through a Vox Buckingham cabinet

• Vox AC15 Hand-Wired

• Vox AC15 through a Marshall cabinet with two alnico 12" speakers

• 1964 Vox AC30

• 1967 Vox Berkeley II with 2x10 cabinet

• Vox 730 head through a Vox Buckingham cabinet

Effects

• Boss DC-2 Dimension C chorus

• Boss DD-2 Digital Delay

• Colorsound Tremolo

• Digidesign Eleven Rack multi-effects unit

• Ibanez TS5 Tube Screamer

• Ibanez TS808 Tube Screamer

• Matchless Hot Box preamp

• Vox Stereo Fuzz-Wah

Strings and Picks

• Assorted D'Addario sets (.010–.046 and .009–.044)

• Fender medium picks

I tried to write something that would incorporate that same tone, and on the album I left the solo spot open for Brad. I thought it would be cool to have Brad come and play on it because the track was inspired by the fact that he liked the tone so much. He has such an unpredictable style: a lot of technique and a lot of humor at the same time. When he plays, you never know what's going to come out.

Do you store your guitars differently now, having experienced the flood, even though you're based in Southern California?

Well, I never leave them on the floor, I keep them up on something. I do have a sump pump in the backyard, just in case. And I left that storage facility in Nashville and moved to a different one, which is far away from the river.

On The Returning, the Gypsy jazz outing, you use everything from clarinet to bouzouki. How'd you get into playing such a range of instruments?

My first instrument was piano. I started when I was 5 years old, then started playing clarinet and then fretted instruments. I had my first ukulele when I was 10 and my first guitar at 12. So I was used to practicing different instruments from an early age, and the skills I picked up on one instrument transferred to another. I took what I learned on the clarinet and applied it to saxophone, took what I learned on guitar and transferred it to the mandolin and the Dobro, and what I learned on piano to keyboard and organ. So, I basically look at it as three different groups of skills.

How do you determine what instruments to use?

If I'm going to record a part on one of my records, it's got to stand up to my skills on guitar, or else it will sound bad.

What instruments can't you play?

There are some instruments I'm not as confident on. I can play the bassoon, but only for a short time. If I have enough time, I can play a satisfactory Dobro part, but I wouldn't hire myself out to play for someone else. Flute, I can get a little something out of. And it kind of depends on the parts, too. Some can be technically challenging.

On another note, how have you found your own voice within the Gypsy tradition?

I would have been happy just to lead a Django tribute band, but it seems like music often has its own journey—it sort of chooses what it wants to do. It was a very natural process for me. I've loved the style since I first heard it back in 1979. And back then there was really no scene. It was kind of underground. I realized at the time it couldn't be a career music for me, so I pursued it for enjoyment and did other music for a living.

Over the years, more people became interested in Gypsy jazz, and in the late 1980s, beginning with my album After You've Gone, I began writing in the style. The next Gypsy jazz album I did, in 2003, was called Franco-American Swing. By that time there was more of an established scene for the music, and I was asked to recreate two tracks for a film featuring Django Reinhardt called Head in the Clouds. It was great to actually get paid for something I would have done anyway—to transcribe and learn exactly what Django played.

In any case, when I finished Franco-American Swing and started touring in support of it, I needed more material than what was on the album, and so I started bringing in some of my other compositions from other styles—for example, a piece from the Hellecasters called “Le Journée des Tziganes," which was influenced by Eastern European folk music. And when I brought in flamenco, classical, and other influences from outside of the Gypsy jazz tradition, things got really interesting.

It seems like you've repurposed some non-Gypsy material in a cool way on the disc

There's one called “Istiqbal Gathering." That's a piece I originally composed for full orchestra, with cimbalom [a large Hungarian dulcimer], violin, and guitar as soloists. I don't get the chance to perform with a full orchestra that often, so I adapted it for quintet, and it worked really well. And strangely enough there's one song I recorded in two different styles—“Sand Away the Years" and “It Only Takes a Secret." This might seem counterintuitive or strange, but I heard the melody played two different ways, with different keys, grooves, and tempos.

You recorded From the Crow's Nest, your bluegrass disc, in Sheryl Crow's barn. What was that like?

It was a really cool barn, a functioning one. The studio was on the second level and horses were underneath. There was this very cool Western décor and theme. Being up there felt isolated, in a good way—a creative cocoon. We were really able to put out the rest of the world for the three days we were there. We got all those tracks done, and there was a very minimal amount of overdubbing and re-singing.

How much 6-string did you play on the record and what guitar did you use?

I'm mostly the mandolin player on this, but I did play guitar on a few cuts, and I used a Blueridge BR-260A, which is a great dreadnought with an Adirondack top and rosewood back and sides. For mandolins, I used a Gibson F-5L, which I bought new in 1980—I've been the only owner—and a Kentucky KM-1000. On that one, to get a little more of a ringing sound when crosspicking, I dropped in an aluminum bridge saddle.

Who are your benchmarks when playing bluegrass guitar?

Definitely Clarence White and, through him, of course, Tony Rice. And then there's Doc Watson. Those are probably my three favorite players. They're on the same continuum to me. I also think Bryan Sutton is fantastic. He's probably my favorite current player.

How does it feel to travel between different styles like you do on Divertuoso?

When I look back over 40 or so years so far, it feels natural because of the way in which the styles dovetail. But the logistics can be challenging—figuring out how to get the right gear to the right place at the right time. Last summer I had to make a chart to determine what I could fly with and who might be able to loan me something for a given gig. When I play bluegrass I need a mandolin and a flattop guitar. When I play Gypsy jazz I need a guitar, a bouzouki, and a clarinet. And at an electric show, I need at least two electric guitars and a pedalboard. You can only travel with so many pieces at a time.

How do you tie everything together?

Probably the first thing is melody. No matter what style of music I do, I'm always attracted to a more melodic composition. And on all three recordings, I set out to make music you don't necessarily have to be a guitar player or musician to enjoy. Instrumental music might be more attractive to musicians, but hopefully the melodies are strong enough to hold anyone's attention, even if they don't know the first thing about music.

YouTube It

Here's a high-quality video of John Jorgenson playing the Django Reinhardt standard “Nuages" with his Gypsy jazz unit. Jorgen plays solo until the 2:30 mark, when the ensemble steps up—only to fall back again to let Jorgen fly at 6:30.

Try playing these bright moments from all three discs in John Jorgenson's Divertuoso.

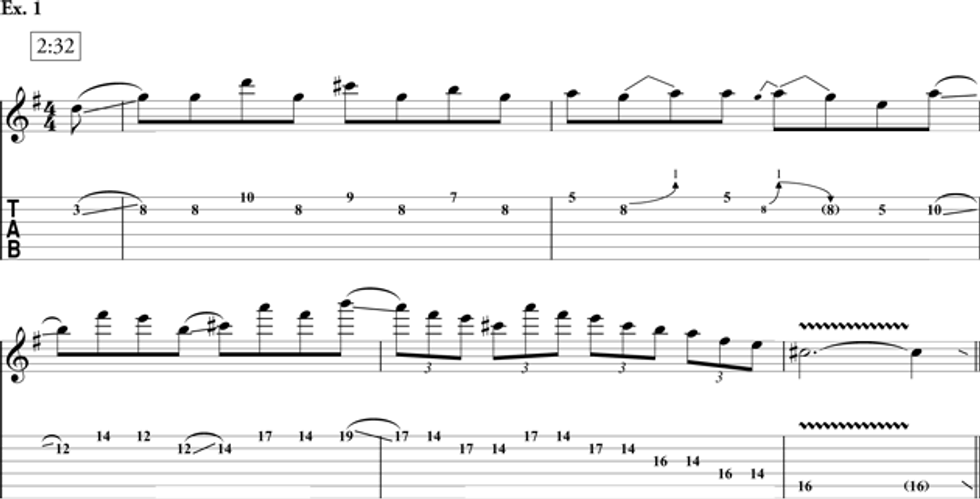

In Ex. 1 from “'61 SG LP" on Gifts from the Flood, Jorgenson makes the first nice electric guitar he ever owned really sing.

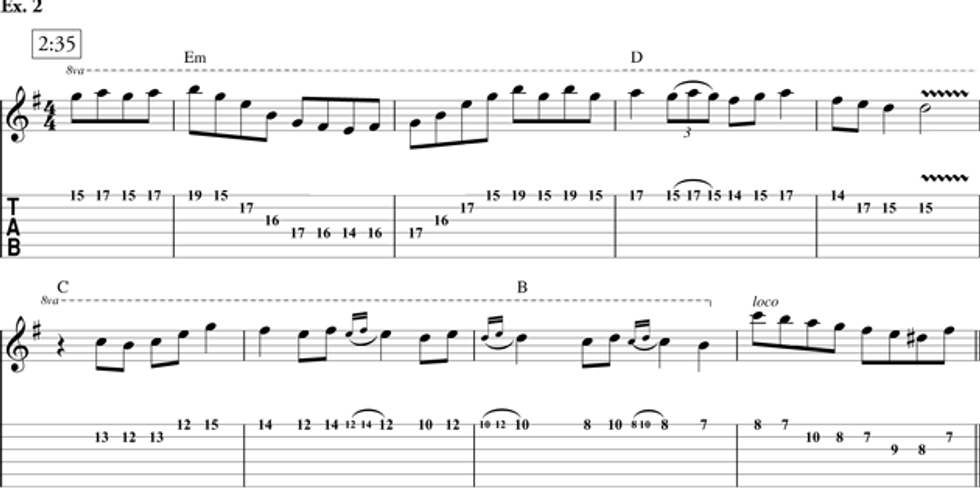

Jorgenson visits the highest region of his 1942 Selmer in this fiery excerpt (Ex. 2) from “Sonora Spring" on The Returning.

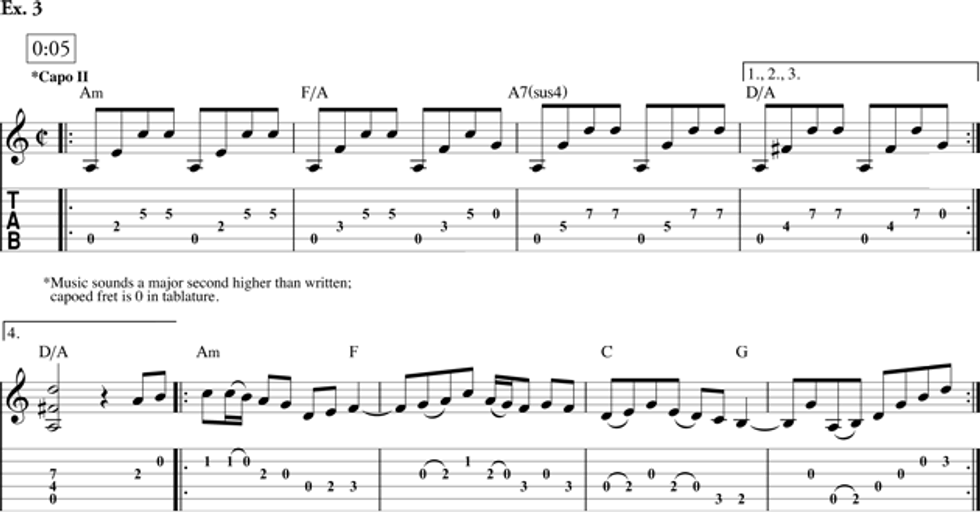

On “Feather," from J2B2, Jorgenson plays a repeating four-bar progression (Ex. 3) sounding less bluegrass than hair metal, before tucking in to some more idiomatic picking.