They’re famous for cheeky videos full of booze and entrails, but there’s a lot more going on with Only Ghosts—their new Ross Robinson-produced LP full of pulsing Sunn amps, 5-string Mustangs, and vintage stomps.

Most people know Red Fang from their videos, which are epic, if not misleading—because there’s a lot more to the Portland, Oregon, quartet than Pabst Blue Ribbon, beer-crazed zombies, cartoon princesses, vengeful nerds, and mindless destruction.

For starters, the band’s riffs are unconventional and almost never in 4/4. Guitarists David Sullivan and Bryan Giles (who also often handles vocal duties) juxtapose angular lines, rage through constant time shifts, and create a sense of tension, release, and musical sophistication. “The song will be trucking along, and suddenly you’ll get to this weird part in five or seven,” says Sullivan. “We enjoy that—it makes it more interesting for us.”

But the Fang guitar team, together with bassist/vocalist Aaron Beam, also avoids simple blues patterns and clichés, often incorporating a healthy dose of dissonance and feedback to keeps things interesting. “We try to break out of the same patterns you hear all the time,” says Sullivan. “We’ll do a weird chord that sounds wrong, but works in the context of the song.” Giles agrees. “A lot of being in a band for me is exorcising negative thoughts that are swirling around in my brain,” he says. “Tritones and real grating elements express that angst better.”

Dynamic contrasts are important, too. They are often dramatic, prevent ear fatigue, and make the heavier parts sound even heavier. Only Ghosts, Red Fang’s latest release, proffers a lot to learn about strategic placement of layered sounds and ambient textures within the context of heavy grooves.

But the secret sauce—what gives Red Fang true depth—is its members’ diverse tastes and influences: Perhaps unsurprisingly, Giles and Sullivan grew up on Sabbath and Maiden, but they’re also into ’70s British post-punkers Bauhaus, country legend Willie Nelson, avant-rocker Captain Beefheart, and even pop icon Justin Timberlake. “I just like good music,” Giles says. “It doesn’t have to be hard rock at all—although for playing music, I have always gravitated toward the darker end of the spectrum.”

We recently spoke to Sullivan and Giles about writing and recording Only Ghosts,their fourth LP and first with producer Ross Robinson (Slipknot, At the Drive-In), how they divvy up guitar duties, and what’s up with Giles’ bastardized 5-string vintage Mustangs.

Do you guys write riffs together as a band or come to rehearsal with ideas you worked out at home?

Bryan Giles: We try not to limit ourselves to one technique or another. What I like to bring into practice are two parts that seem to go well together—that’s a good starting place. If you just have one riff, you can find yourself playing it over and over and getting nowhere, so as a kick-starter I like to have an A and a B part. The riffs seem to have a better chance of surviving if they have a buddy to go along with them. So we’ll work on those, and hopefully it sparks inspiration for the other guys. If it does, then it starts mutating and we’re off to the races.

David Sullivan: There’s not really one main songwriter. Me, Aaron, and Bryan bring in ideas. Sometimes it will be almost complete songs, sometimes it’ll just be a couple of riffs. At practice, we put them together, flesh them out, and make them into actual songs. It’s all of us doing that together.

A lot of your music is in odd meters. Is that on purpose or is that just the way the riffs turn out?

Giles: I was in a band for about eight years called Last of the Juanitas, and it was instrumental math rock with constant time shifts—crazy, Rubik’s Cube songwriting. I did that for a long time and then started thinking to myself, “Why are we purposely trying to thwart someone who might want to rock out to a song?” So I started a band with John and David called Party Time—the name was sort of our mission statement.

FACTOID: Red Fang’s Only Ghosts was recorded over the course of a full month’s worth of 12- to 14-hour days in the studio—a pace set by producer Ross Robinson.

Sullivan: We all like stuff that is a little out of the ordinary. Another band I was in was called Shiny Beast, a name that was a nod to Captain Beefheart. It was a three-piece, mostly instrumental, and intentionally doing odd times, weird chords, and dissonance. I really like when a beat or a riff has an odd time signature, but you don’t really notice it. You can nod your head right along and it still works and doesn’t feel weird.

From the looks of your raging audiences, it seems they don’t realize anything unusual is happening.

Giles: We can attribute a lot of that to John’s drumming. We’ve been punishing him with these bizarre things for so long, he’s really gotten good at finding the flow in something that absolutely doesn’t, theoretically. We do a song on [2013’s] Whales and Leeches called “1516,” and that’s because it’s in 15/16. When we were first writing that song, we were playing it and John was like, “Guys, there is something really wrong with that riff.” And we were like, “No man, it’s awesome.” He screwed up his face and said, “You’re dropping a beat.” That was going to pose a problem for him, so we were like, “Okay, let’s put that beat back in.” So we put it back in, but nobody in the string section was happy. It was like, “No—it was way better the other way.” It made a lot more work for John, but if you listen to that song, unless you’re counting it out you’re not going to notice. I mean, the odd time makes it more frantic sounding, but John certainly makes it sound straight, too. I love when he does that. I feel like I can get away with writing more fucked up things because of his smoothing techniques.

You guys are big fans of dynamics, too, though.

Sullivan: You’ve got to have some contrast in there. It almost becomes monotone if everything is trying to be heavy. Within a song, you need a part that builds up and then the big heavy part has more impact. So that is definitely something we try to do—not just make it always at full volume. Sometimes we’ll tone down the part before, or we’ll put in a transitional part, or have a little more build-up, or even a tension-building part. Sometimes we’ll hold a note a little longer than it feels like it should be, and then you get that release at the end of it.

Giles: If you’re listening to death metal or something and it’s full speed ahead—double kicks and super-fast guitars—it loses its impact, because there’s nothing to compare it to. If you put in a prettier, more laid-back element and then you go back into the super-fast stuff, that’s where you’re going to feel it. The punch isn’t going to hit if you never pull back and swing it again.

YouTube It

Get a close-up look at one of Bryan Giles’ heavily modded 5-string Fender Mustangs as he begins “Prehistoric Dog” at a 2014 metal fest in Viveiro, Spain.

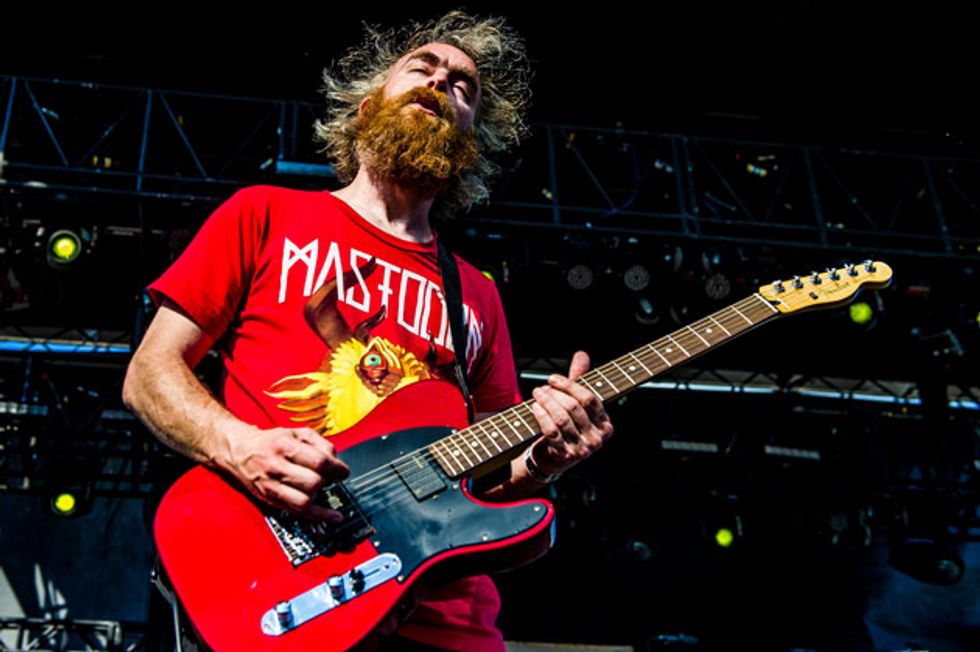

Giles and Sullivan (shown above onstage in 2012) were friends before joining forces to form Red Fang. “I had heard his band Last of the Juanitas,” Sullivan says. “I was in Shiny Beast and we were both doing similar things: math rock, noise rock, and trying to do weird time signatures and dissonance.” Photo by Chris Schwegler

How about with low tunings—does using standard sometimes make the lower stuff sound heavier, too?

Giles: We do dropped-D and dropped-C a fair amount—more dropped-D. I don’t think there’s any dropped-C on this new record. The challenge I have using dropped-D is that hitting that open chord is so satisfying you end up wanting to write all the songs in D—you find yourself hanging around in D the whole time and that can get pretty boring. We try to write songs in different keys in those dropped tunings. However, I don’t think the dropped tunings necessarily make anything heavier or evil. One of our harder-hitting songs, “Prehistoric Dog,” is in standard and centers around B, which is well up there on the neck. A lot of times the dropped tunings can end up being a crutch and they can stunt your songwriting. I try to either stay away from writing in the key that the guitar is tuned down to, or just not tune down at all.

How do you divvy up the guitar duties?

Sullivan: Mostly it just happens. When people ask us who is the lead guitar player, neither one of us wants to be the lead player. But because Bryan also sings, I guess that’s one thing that leads to how we divide things up: If something is a little tricky to play and Bryan is also doing vocals, then I’ll usually play that.

Giles: I sing a fair amount, so a lot of times the more intricate or difficult guitar parts I’ll leave to David. I’ll write a part that’s really minimal while I am singing so I don’t have to concentrate on both so much. I think David has more style. I enjoy his stuff, so I push him to do more of the leads. When I do leads, they end up being more skronk, which has its place, but I don’t want to be doing these minor-seconds all over the place—that can become unpleasant for people. I mean, I like them, but he does more of the musical, vocally oriented guitar lines, which I think maybe are more interesting for the average person to listen to.

David, do you look at the Mustangs Bryan plays almost as a different instrument, since he only puts five strings on them and tunes them differently?

Sullivan: A lot of times we’re playing the same thing. But because of his tuning he can’t do that bend where you take the power chord shape, invert it, and then bend up on the G and do that rock ’n’ roll squeal. He doesn’t use standard tuning, so he can’t do that, but I do it a lot. I feel we could do more to complement each other by doing different things.

—Bryan Giles

But on the new album you can totally hear different, complementary parts. “I Am a Ghost” is a good example.

Sullivan: Part of that was Ross’ [Robinson, producer] suggestion. Initially, I was playing what Bryan was playing, and Ross was like, “Drop out on some of these parts and just accent a couple of chords from what the main riff is.” But even before I met Bryan, I had heard his band Last of the Juanitas. I was in that band Shiny Beast and we were both doing similar things: math rock, noise rock, and trying to do weird time signatures and dissonance. I think even without knowing each other we had the same feel for things. We like the same kinds of noisiness or whatever.

Bryan, what inspired you to play 5-string?

Giles: It was a long time ago. Mustangs have loose saddles on the bridge, and I was playing a show and my high-E string broke. The next day, I was getting my guitar out and realized I lost the saddle. “Damn it!” So I bought another one and put it back on. Maybe a couple of months later I lost it again. At that point I was like, “You know what, I never play that high string anyway.” So I just started stringing it 5-string normal tuning [without the high E]. Then I started doing the E-A-D-G-G tuning. The unison Gs were inspired by stuff like Sonic Youth, Glenn Branca, more prog-y kinds of things, and just experimenting with stuff. The unison is basically for single-note solos or going up and down the neck on just those two strings. They stand out really well when you’ve got them doubled up like that—and it’s easy! [Laughs.]

Do you use the same gauge on those two strings?

Giles: I’m doing .017 and .014 right now.

Why is the higher one thinner?

Giles: I think it makes it a little weirder. I tried it with the same gauge, but I think the times when it goes slightly out of tune makes for more interesting sounds. If they are tuned the same and have the same gauge, then it almost nullifies the unison. Whereas if one is a little slacker, I find it’s the little “squibbles”—that’s a technical term!—that I like.

Bryan Giles’ Gear

Guitars5-string 1964 Fender Mustang

5-string 1965 Fender Mustang

Amps

Sunn Beta Lead head

Orange 4x12

Effects

MXR Bass Octave Deluxe

Strings and Picks

Dunlop Heavy Core strings (.014–.048, with .051 on bottom for dropped-C)

Dunlop Tortex 1 mm picks

David Sullivan’s Gear

GuitarsNik Huber Krautster

Fender Thinline Telecaster

Amps

Sunn Beta Lead head

Orange 4x12

Effects

MXR Phase 90

Mooer Ninety Orange

MXR Bass Octave Deluxe

EarthQuaker Devices Dispatch Master

Smallsound/Bigsound Mini

TC Electronic PolyTune 2

Strings and Picks

Dunlop Heavy Core strings (.010–.048 for standard tuning, .011–.050 for dropped-C)

Dunlop Tortex .73 mm picks

So your Mustangs have a 5-string nut and a 6-string bridge with a missing saddle?

Giles: That’s correct. I was having the guitar refretted by my friend Maureen Pandos [of MDP Bassworks in Portland], and when she was setting it up she said, “Do you still want to just do five strings?” I said, “Yeah,” and she said, “Do you

want to commit to it? If so, I can make you a 5-string nut and then you’ll be able to use more of the fretboard.” I said, “Fuck it.” So there it is. It is nicer with the 5-string nut. Before, there was a 1/4" of the neck that wasn’t getting utilized—now the strings are nice and equally spread out.

Both of you use a Sunn Beta Lead, which is a solid-state amp.

Sullivan: Our bass player, Aaron, had a collection of them, so one day we were practicing and decided, “Let’s see what it sounds like if we all

play Beta Leads.” It sounded good and we stuck with that. I know a lot of people, especially in the geek gearhead world, think solid-state amps suck compared to tube amps, but I really like the sound of them.

Giles: The instrumentation blends nicely when we’re all using the same amps—although quality control went out the window with that company

and they ended up imploding. On some of those amps, you’ll turn the master volume to 1 and barely be able to hear it. On others, you put the master volume at 1 at it is way too loud. We’ve had them taken in, repaired, and looked at. We’ve got at least two each now that work well.

Does all your distortion come from the amp, or do you use pedals, too?

Sullivan: I do have a distortion pedal on my board now, but I use it more as an EQ shift than anything—just to make it pop out. But for years and years,

I just had a tuner and an MXR Phase 90. The distortion was all just the amp.

What do you use on tour if you can’t get one of those heads?

Sullivan: We carry them with us. The other thing that’s nice about them is that they’re fairly small. That’s usually our carry-on for me, Bryan, and Aaron—we put them in the overhead bin on the plane. When we’re in Europe, we just rent these step-down transformers for the power difference.

This was your first time working with producer Ross Robinson. What did he bring to the table?

Sullivan: This is the first time we’ve worked with a producer who was more hands-on in terms of helping us arrange songs and working things out. For the previous two records we worked with Chris Funk—and he was great—but he was more keeping us focused on what we needed to do, or he would be a tiebreaker and help us make decisions when we weren’t sure about something. But Ross was more like, “I’ve listened to the song and I feel like you guys could take that bridge and make that into an intro,” or “This verse should really be the chorus.” We gave him an arranging credit on the album because he really did help us structure some of the songs.

Giles: It was a really intense and really rewarding experience. I’m happy to have done it. It was exhausting—it was 31 days straight. We did somewhere between 12- and 14-hour days, every day, for a month. He is just such a hard-working guy. He dives super deep into the songwriting process and everything. He was definitely an inspiration. You’re like, “If he’s not taking a break, I’m not taking a break.”

Sullivan: Pedals for sure. At first I was a little bit overwhelmed. I went in there to do some overdubs, and he’s got a lot of vintage Electro-Harmonix stuff and a lot of old MXR stuff, and he hooked all this stuff up and it sounded a little too crazy for me. He was throwing on a lot of stuff and I was like, “I don’t know about this.” But then we listened to it in the context of the song and I thought, “Yeah, this works really well.” And while I was tracking he would be turning knobs—he would be changing the pedals as I was playing sometimes—to emphasize a part or to give it more life. It wasn’t just the pedal setting: It was him manipulating the pedals while I was recording it. That was cool, and also something I never experienced while recording.

Giles: Ross had what we called “the pedal puddle”—like, a Memory Man and some other stuff all stacked on top of each other. At points, I couldn’t even tell what was happening. We’d be tracking and I’d be playing along, sort of knowing that I was playing in the key of the song, but it just sounded insane. I mean, I enjoyed it, but I was like, “I don’t have any idea what’s going on!” Joe Barresi, who mixed the album, probably got hundreds of tracks to weed through and really did find some of the coolest weirdo moments. He put them in in a way that was not at all jarring. They made sense. For stuff that was real left-field noise, he massaged it well and I was really impressed.