The folk-rock icon takes PG inside his intimate new Lighthouse LP, and shares the surprising story behind his all-time favorite flattops—and they’re not the American mainstays you’d assume.

Five decades into his storied career, David Crosby should need no introduction to anyone seriously interested in guitar playing or songwriting. There are, of course, latecomers to every party, so we’ll start here with a few highlights from his musical life, for those of you who may not know Croz’s story.

Along with fellow singer-songwriters Roger McGuinn and Gene Clark, Crosby was a founding member of the popular and influential folk-rock group the Byrds. Their 1965 cover of Bob Dylan’s “Mr. Tambourine Man” was a massive hit in America and the U.K. McGuinn played 12-string electric guitar and sang the lead vocal, with Clark and Crosby sweetening the choruses in tight harmony. A year later, the Byrds released their original song “Eight Miles High,” showcasing the band’s newfound interest in bold-toned psychedelia.

Crosby left the Byrds in ’67 and soon launched Crosby, Stills & Nash with Stephen Stills (of the folk-rock band Buffalo Springfield) and Graham Nash (of the Hollies, a successful pop group from the U.K.). Their self-titled 1969 debut album spawned the now-classic songs “Marrakesh Express” and “Suite: Judy Blue Eyes.” Crosby’s most prominent outing on the album was “Guinnevere,” a hypnotic ballad with shifting time signatures in E–B–D–G–A–D tuning (low to high). From time to time, CSN expanded to include Neil Young (also a Buffalo Springfield alum), as on the multi-platinum 1970 album Déjà Vu.

In 1971, Crosby recorded his first solo album, If I Could Only Remember My Name, which featured the hallmarks of his singular style—luscious vocal harmonies, acoustic guitars in alternate tunings, and surprising harmonic twists. For someone with such a strong artistic vision, however, Crosby has had a relatively scant solo output since that time. Although he’s put out a few live albums along the way, he’s released just four studio albums since his solo debut: 1989’s Oh Yes I Can, 1993’s Thousand Roads, 2014’s Croz, and this year’s Lighthouse (’16).

If you were to track Crosby’s musical progression as a solo artist and try to predict the type of record Lighthouse would be, you’d probably be dead wrong. Over the years, he has generally made records with hotshot session players and contemporary production values. Even the recent Croz is cut from that same cloth. Lighthouse, however, is a remarkably bare-bones album full of thoughtfully crafted songs, captured intimately. Coproduced by Michael League (bassist and skipper of the band Snarky Puppy) and Grammy-winning engineer-producer Fab Dupont, it features up-close-and-personal production that gives it a slightly modern feel, while the spare arrangements supporting Crosby’s rich voice and inventive acoustic playing harken back to his early-’70s solo work.

Inasmuch as the music and sonic textures on Lighthouse are like anything Crosby has released in the past, they’re most akin to the songs “Traction in the Rain” and “Orleans” from If I Could Only Remember My Name. Just as on those older sessions, there are no drums at all on Lighthouse. Instead, the musical pulse comes from the acoustic guitars, which are played by Crosby and League, whom Crosby first worked with when he was a featured guest on Snarky Puppy’s Family Dinner – Volume 2 earlier this year.

Snarky Puppy is known for having an abundance of technical chops, but it seems it would take a take a wholly different set of chops to support what you do. What gave you the confidence that Michael League was the right guy to make Lighthouse with?

As soon as I started working on that Family Dinner record, I pretty much knew right away that I wanted him to produce a record for me. He’s just a startlingly talented guy. My thought about getting him involved was sort of like hiring a master carpenter with a gigantic toolbox, all these great players—namely, Snarky Puppy. I thought that’s where we would go. I said, “Hey, I’d like you to do this and we could use all the guys from the band.” He came back with, “Well, I’d love to do it but I really loved your first solo record. Rather than doing band tracks, I’d like to do a more acoustic-guitar thing with big vocal stacks.” Of course, that’s right in my wheelhouse. That’s exactly where I live. And that’s what we did.

It’s so different from your last record!

Croz is more a band record. Lighthouse is an acoustic record. I deliberately wanted to do that—I want to go in both directions.

Recording and mixing apparently took a lot less time than you anticipated, too, right?

It was so embarrassing. I said to Michael, “I need a month,” and he said, “You don’t need a month. We can do this in two weeks.” I’d never made a record that quickly in my whole life, but Michael told me, “It’s easy. We can do it.” I was so sure we couldn’t, but once we got into the studio we recorded the whole album in just 12 days—then mixed it in four.

What made that sort of pace possible?

Being comfortable with each other and working with very talented people. Michael brought an engineer onboard—Fab Dupont—who is incredibly good. The three of us communicated extremely well.

What would you say League’s greatest strengths are as a musician?

He’s happy, he’s focused, and he knows exactly what’s important to him. Those are three gigantic gifts.

On the flip side, what would you say your strengths are?

I’m happy and I love making music. Aside from my family, this is my greatest joy. It’s the most fun you can have with your clothes on, really.

Are the songs on Lighthouse all brand new?

Sort of. I’ve been working on this batch of songs for a while—probably two years. I first started writing “The Us Below,” “Somebody Other Than You,” and “Things We Do For Love.”

You wrote some of the new songs with League, right?

I have been writing a ton lately—mostly with other people, like Michael, and with my son James Raymond. They’re the two guys I write with the best. I like writing with other people.

Why?

If you write with somebody else it doubles the possibilities. I’m not here to prove anything to anybody. Writing with other people works great for me.

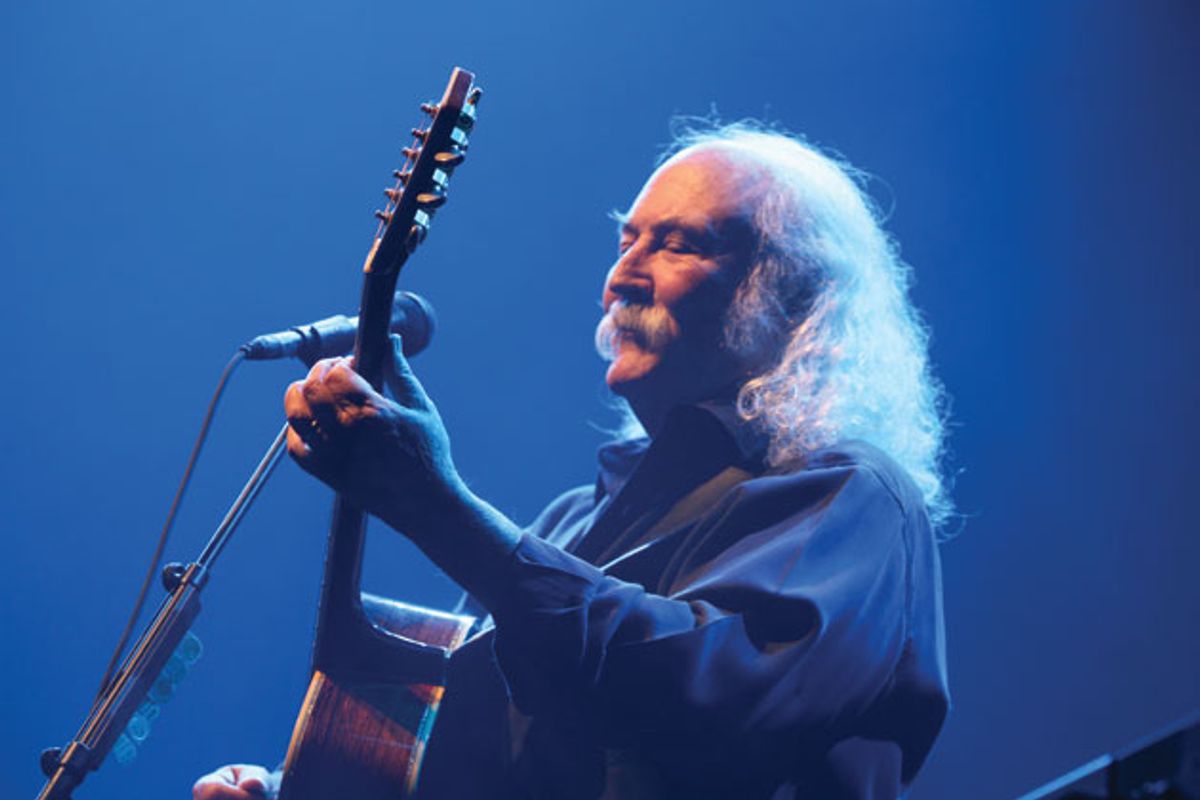

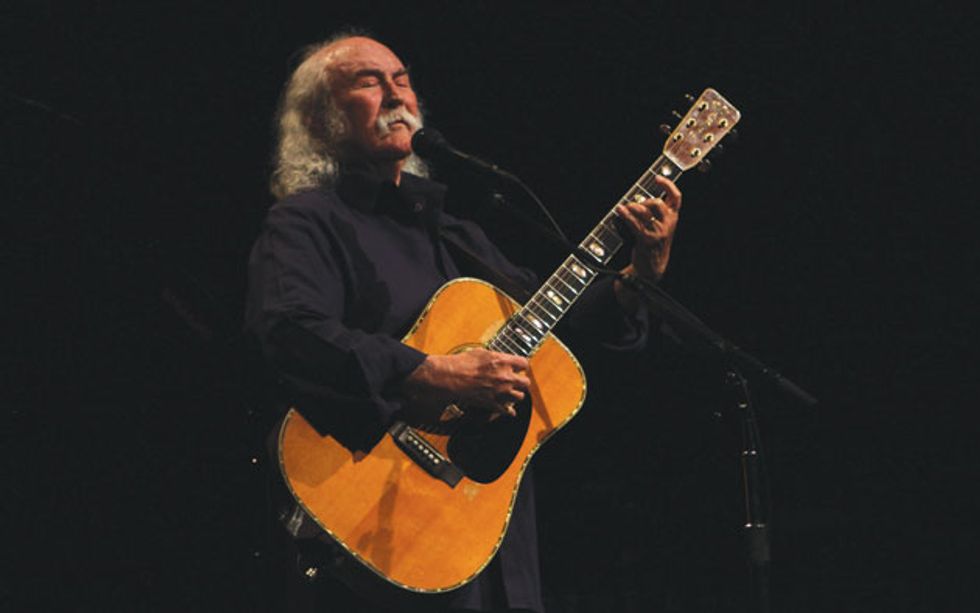

David Crosby with one of his Martin D-45s. “I’ve got three of them that I bought at the same time, in ’69,” he says.

Photo by Django Crosby

One thing that’s been a constant of your music over the years—going all the way back to “Guinnevere”—is the use of nonstandard tunings. We hear that again throughout Lighthouse. How’d you first get into writing songs in odd tunings?

I’m fairly crazy with tunings, but you’ve got to remember I learned it from people who were better than me—Joni Mitchell and Michael Hedges, in particular. Hedges was the master. I think he was the best guitar player of the last century. He and Joni both explored tunings more than anyone.

Can you tell us more about what you learned from Joni and Michael?

Well, I don’t mean they sat down and give me lessons. Hedges and I wrote together, we played together, we recorded together. I was living with Joni because she was my girlfriend, and it was a real head stretcher. I’d be working hard on a song and I’d play it for her, and she’d go, “That’s nice, David,” then play me three songs that she’d just written the night before. It was a little intimidating.

On Lighthouse, are there one or two main tunings that you favored, or is each song in its own tuning?

I used five different tunings on the record, at least. The two first songs—“Things We Do for Love” and “The Us Below”—are in the same tuning, Eb–Bb–D–G–Bb–D. It’s my new favorite.

Your harmonic sensibility is really striking in terms of how you shift from one mode to another within songs, with apparent ease. And it’s a skill it seems you’ve had for as long as you’ve been writing and recording. How did you develop your ears?

I always want to have those dense chords in there—much thicker, tone-cluster kinds of chords. That comes from me listening to jazz keyboard players, wishing I could play that.

Do you play piano?

A little—enough to write songs. My son James is a brilliant keyboard player, so I don’t have to.

When you’re writing in odd tunings, do you think about the literal names of chords—like, Bm7(add11) or what have you?

No, I’m almost completely illiterate about music. I don’t know diddly.

What guitars did you and Michael play during the Lighthouse sessions?

We used two of my 1969 Martin D-45s. I’ve got three of them that I bought at the same time, in ’69. Lundberg’s [Fretted Instruments, now defunct] in Berkeley had a bunch of them. I went there and cherry-picked the three best ones. If you know about Martins, you know about the legendary D-45—everybody has always wanted one. We also used three of my McAlisters on this record.

David Crosby’s Lighthouse Gear

Guitars

Two 1969 Martin D-45s

Vintage Martin converted D-18 12-string

Custom McAlister Concert model

Custom McAlister Concert 12-fret C

Fender Stratocaster

Alembic 12-string electric

F Bass Hammertone OC12 octave 12-string solidbody

Strings and Picks

Herco nylon picks

D’Addario EXP16 acoustic strings (.012-.053)

What’s the story with the McAlisters?

Roy McAlister is a guy who showed up at my house about 10 years ago and said he had built me a guitar. I thought, “Oh, no—this is gonna be terrible and I’m going to have to be nice about it!” He brought out this triple-O-sized thing, put it in my hands, and, man, it’s the best guitar I’ve ever played—just a flat-out stunner. So now I own five McAlisters, and I would count him as probably my favorite guitar builder alive. There are a lot of guys who are good: James Olson is really good, and if you haven’t seen a Micheletti, take a look at one. He’s doing things that nobody else is doing—he’s very experimental and a very fine maker. Still, my favorite is Roy McAlister.

What’s so special about his guitars?

He has some kind of magic with finding fantastic top wood. A lot of cross-grain, a lot of bear claw. He builds guitars that sound as good as the other guitars right off the bat—before they open up and really get their voice. They’re just freakin’ cannons.

What other guitars did you use on this record?

A Strat, an Alembic 12-string electric, and a little Hammertone octave 12-string electric—they’re brilliant. We also used one of my Martin 12-strings, which is a converted D-18 that I’ve had since before the Byrds.

It sounds like you’ve got quite a collection.

It’s funny, other people collect guitars for other reasons. They collect them because somebody famous owned them, or because they’re great looking, or because they’ve got a whole lot of inlay on them. I get them because they sound good. If I run across a guitar that sounds spectacular, that’s got unbelievable overtone structures and is really great to play, that’s what makes it for me.

What songs is the Hammertone on?

It’s on several of them, but you can really hear it on “Things We Do for Love” in several places.

You mentioned a Strat—who plays the wild electric-guitar solo on “The City”?

That’s Michael. It’s just crazy, because he didn't tell me he could play guitar. As a matter of fact, he told me he couldn’t. But he can.

So, when you two write together, it’s on guitars?

We write on acoustic guitars.

Is he fluent in tunings the way you are?

Absolutely—he’s a brilliant musician. I don’t want to throw the G-word around, but he’s a really gifted guy and can play anything that he wants to play. And he sings and writes words and music. He does it all.

There are no drums on this record, only some light percussion—tapping the side of the guitar on “Look in Their Eyes” and “The City.” That’s a bold choice, considering how much music today is beat driven.

We did that on purpose. I think it swings anyway.

It’s a tricky place to go, but it seems to me that we did it [successfully]. Truthfully—and I know I’m being immodest here—the quality of the songs is the most sustaining thing on this record. These songs are pretty good.

YouTube It

In this album-teaser video, we get aural and visual glimpses into the making of Croz’s latest solo album with collaborator Michael League and others.

Lighthouse was tracked and mixed in merely 16 days. “I’d never made a record that quickly in my whole life,” says Crosby.

Engineer Fab Dupont on Recording Lighthouse

Fabrice Dupont—or “Fab,” as absolutely everyone calls him—was coproducer, as well as recording and mixing engineer for David Crosby’s latest solo outing, Lighthouse. The sessions were tracked at Jackson Browne’s Groove Masters studio in Santa Monica, California. The mixing was done at Dupont’s Fabulous Room at Flux Studios NYC. Dupont had worked with Lighthouse arranger and coproducer Michael League on other projects before, but this was his first time in the studio with David Crosby. The album features guitars and vocals captured in glorious detail, with stark, complex arrangements providing evocative soundscapes for each song. Lighthouse is a remarkable achievement, especially considering it was tracked in less than two weeks. The key ingredient, Dupont says, was focus.

“League is a badass,” says Dupont. “I have better things to do than be in the studio and fuck around. We’d come in at 10 o’clock in the morning and at 10:15 we were recording. The vibe was awesome and sometimes playful, but there was no, ‘Should we do it this way or should we do it this way?’ We knew what we wanted. No ego. No bullshit.”

The thing that surprised Dupont most about the 75-year-old Crosby was the quality and consistency of his voice. “He’s just amazing,” Dupont says. “He came through with some of the strongest performances in his career, day after day, under serious pressure.” That said, Dupont and League cut the legendary Crosby no slack. “We didn’t pussyfoot around,” Dupont admits. “If I’m spending my time, I want this to be the best record ever—period. I don’t care if he’s David Crosby or Paul McCartney or whoever. If a take is not the best, I’m like, ‘Dude, do it again.’”

For the acoustic guitar tones, Dupont set up two identical stations for Crosby and League, each with a four-microphone array—a Lauten Audio Atlantis large-diaphragm condenser, a vintage RCA 77 ribbon mic, and newer AEA N22 and R44C ribbon models. “I would have all four microphones coming in on separate faders on the console,” he says. “I always based the sound on the Atlantis, then blended in the ribbons to create different colors for each song. For example, if I were tracking Crosby’s two 1969 Martin D-45s at the same time, on David’s guitar I would maybe blend in the RCA, then use a blend with the newer AEA ribbons on Michael’s side. That gave me enough difference in the sound to have a super-wide stereo image.” Dupont also took a DI signal from the acoustic guitars’ pickups. He says he likes to record the DI signal for security’s sake but rarely uses it in the final mix. “I also thought maybe I could use it to send stuff to effects or reverb.” He did, in fact, use the DI on “Things We Do for Love” to create an unbelievably fat and wide sound out of Crosby’s lone guitar.

During mixdown, Dupont put Crosby’s vocal front and center, with minimal treatment. “You can feel the life,” says Dupont. “That’s why I mixed it that way. I wanted it to be so present and lush—and that’s what we got.”

- Pre-War Perfection: The Martin D-45 - Premier Guitar | The best guitar & bass reviews, videos, and interviews on the web. ›

- Pre-War Perfection: The Martin D-45 - Premier Guitar | The best guitar & bass reviews, videos, and interviews on the web. ›

- David Crosby of Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young, Has Died at 81 - Premier Guitar ›

- The Indelible Imprint of Guitarist & Musician David Crosby - Premier Guitar ›