The 6-string innovator brought a deeper, more fully realized vision of guitar playing to the worlds of jazz and prog rock, and expanded the instrument’s sonic vocabulary.

Allan Holdsworth was a giant among giants. He created a unique musical language that meshed extreme harmonic complexity with mind-boggling virtuosity in a way that defied categorization. His music was not always accessible—and he didn’t care. His approach to the instrument was unlike any other guitarist’s and he unlocked mysteries no one even knew existed.

On April 16, 2017, as many around the world celebrated Easter Sunday, a Facebook post from Louise Holdsworth let the world know that her father had died the night before. He was 70 years old and in the midst of completing a two-disc set for Steve Vai’s Favored Nations label.

As a kid growing up in Bradford, England, Holdsworth’s biggest passion into his teens was cycling, but he longed for a saxophone, so his dismissal of common guitar-isms made perfect sense. Although he cited Eric Clapton as an influence, his musical voice was far more informed by saxophonists John Coltrane and Michael Brecker—particularly Brecker’s playing on Claus Ogerman’s Cityscape.

Holdsworth was born on August 6, 1946. His father, Sam Holdsworth, was a jazz pianist. When Holdsworth was around 15, he’d sneak into pubs with his dad and his brother-in-law to see live music, and he became seduced by the glowing red jewel lights on the stage amps. A couple of years later, he received his first instrument: not a saxophone, but an acoustic guitar, which Holdsworth’s dad bought from his uncle. Soon he got an electric guitar and amp, and, through hearing his dad play coupled with listening to his father’s vast record collection of artists like Charlie Parker and Benny Goodman, Holdsworth’s interest in jazz ignited. Goodman’s guitarist, Charlie Christian, was one of the first to use an electric guitar and developed an approach that was essential to the creation of bebop. Holdsworth started by learning some of Christian’s solos, but soon decided it would be better to find his own voice.

At the suggestion of alto saxophonist Ray Warleigh, who he met at a clinic, Holdsworth made his way to London. There, Warleigh took him under wing. He gave Holdsworth shelter and food, and helped Holdsworth break into the London scene. In the late ’60s, Holdsworth formed ’Igginbottom, his first band that played originals, and joined prog outfits Tempest in ’73 and Soft Machine in 1974.

The next year, Holdsworth left Soft Machine to join drummer Tony Williams. He played on the Tony Williams New Lifetime albums Believe It and Million Dollar Legs. The former featured “Fred,” “Proto-Cosmos,” and “Red Alert,” which became integral parts of Holdsworth’s live sets for decades.

Playing with Williams was among Holdsworth’s most cherished musical experiences and paved the way for some other career milestones. At one of Williams’ shows at New York City’s Bottom Line, the audience included an assortment of music royalty, including George Benson, Todd Rundgren, Elliot Randall, and Miles Davis. Holdsworth was extremely nervous and chugged down bottles of Heineken to take off the edge. But as soon as he hit the stage, all jaws dropped when he unleashed his furious, warp-speed lines. Benson, who was eating dinner, put down his fork and reputedly said, “What the fuck was that?”

Benson got him a deal with Creed Taylor of CTI Records. Unfortunately, rather than afford Holdsworth a proper recording opportunity, CTI instead released Velvet Darkness, a recording of a rehearsal session. This incident was the first of many throughout Holdsworth’s career that made him embittered about the music business.

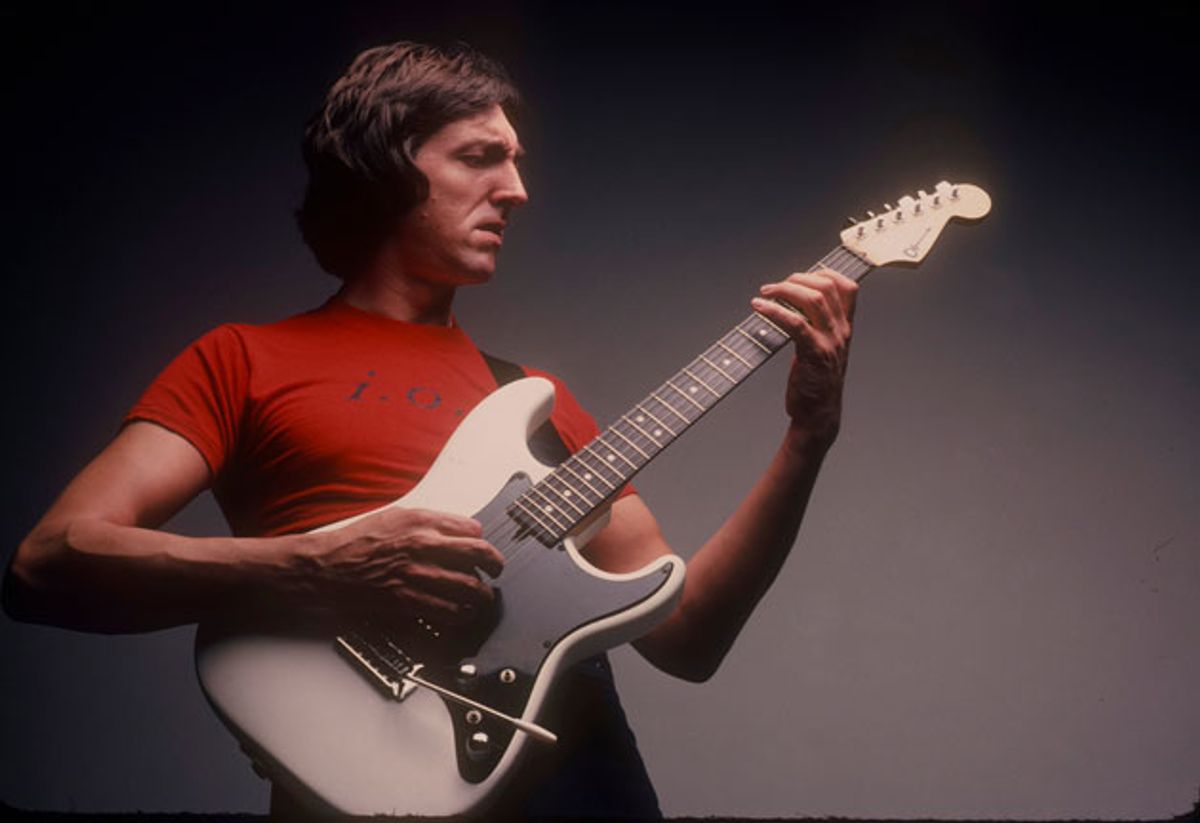

Holdsworth continued to be an MVP sideman in the fusion world. He performed and recorded with the band Gong, violinist Jean-Luc Ponty, drummer Bill Bruford’s group, and pianist Gordon Beck. In 1982, his first proper, studio-recorded solo album, I.O.U, was released. I.O.U. introduced many guitarists and fusion fans to Holdsworth’s sound. Although his vocabulary exploited common jazz sonorities—like diminished and whole tone sounds, along with unusual, symmetrical divisions of octaves derived from his study of Nicolas Slonimsky’s Thesaurus of Scales and Melodic Patterns—his legato approach and warm, voice-like tone imbued his solos with a truly saxophone-like, un-guitaristic timbre. Holdsworth remarked many times that he only played guitar because he got stuck with the instrument, and he actually played violin on I.O.U.’s “Temporary Fault.”

The way Holdsworth executed virtually everything ran counter to conventional guitar performances. His giant hands allowed for four-notes-per-string scale shapes, and he would often play wide intervals, like fourths and fifths, on a single string rather than on adjacent strings, thereby eliminating the percussive sound of the pick’s attack. He also employed string skipping to get spellbinding intervallic sounds that no other guitarist had played before. With fingers outstretched, he played unison notes on adjacent strings to get an effect similar to a saxophonist’s false fingerings. He also used the whammy bar to give his more melodic phrases a voice-like quality.

Most guitarists are immediately drawn to Holdsworth’s incredible single-note facility. He was faster than just about any other guitarist on the planet. But his chordal playing also introduced sounds previously unheard on guitar. One example: Holdsworth took inspiration from the writings of saxophonist and composer Oliver Nelson, who employed close-voiced chords in his music. This led Holdsworth to explore these sounds with another guitarist. They’d simultaneously play separate notes of a closed-voiced chord. Eventually, Holdsworth adopted this concept to just a single guitar, and would reach for unusual chord shapes that included seconds (notes that are a whole step or less apart). These intervals are easy to play on piano, but can be unbelievably difficult to finger on the guitar—particularly for big voicings incorporating other notes—and require large stretches.

After I.O.U. came 1983’s Road Games, Holdsworth’s only major-label release. He got signed to Warner Bros. via Eddie Van Halen, who had been in awe of Holdsworth’s playing since U.K. opened a 1978 tour for Van Halen. Eddie would stand by the monitors each night and watch in amazement. Eddie was supposed to produce Road Games but had to go on tour, so he turned the project over to famed Van Halen producer Ted Templeman. Holdsworth and Templeman ended up butting heads. Templeman wanted an all-star lineup and replaced Holdsworth’s I.O.U. singer and friend Paul Williams with Jack Bruce from Cream. Things deteriorated from there, and Road Games was ultimately released as an EP. Despite all the drama, it garnered a Grammy nomination for Best Rock Instrumental Performance.

Holdsworth’s subsequent release, 1985’s Metal Fatigue, was the game changer that certified him as a bona fide 6-string god. His solo on “Devil Take the Hindmost” became fusion guitar’s equivalent of Eddie Van Halen’s “Eruption.” The virtuosic tour de force was a thrill ride, shifting from inside to outside tonalites at a million miles per hour. The solo was so epic that Steve Vai transcribed it for publication.

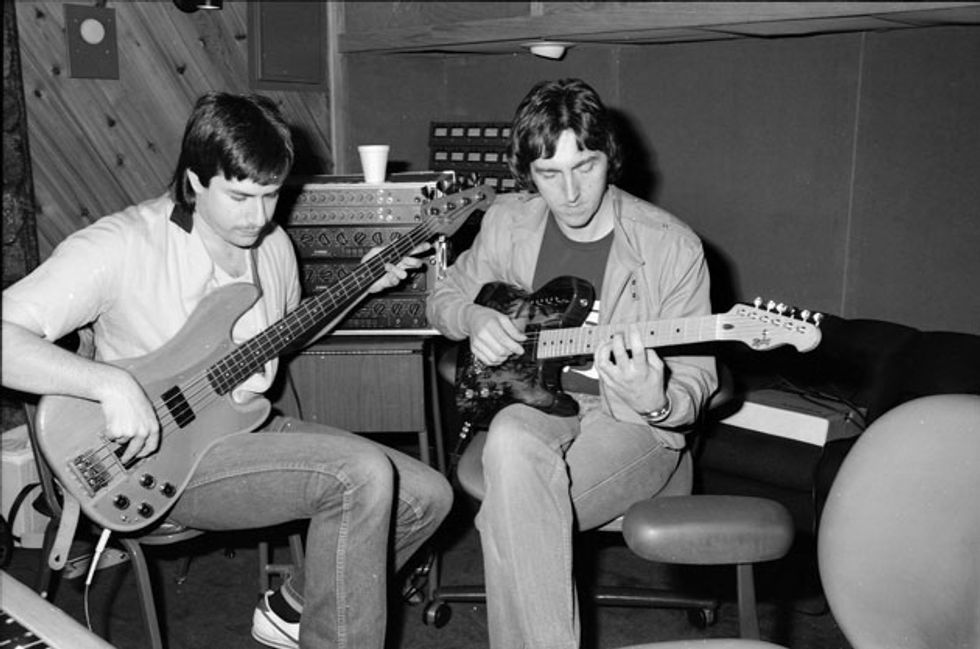

The same year as his ill-fated major-label debut Road Games, Holdsworth huddles in the studio over a new tune with über bassist Jeff Berlin, who would frequently appear with Holdsworth onstage in the late 1970s and early ’80s.

Photo by Neil Zlozower/Atlas Icons

Given the shred craze of the time, it was fitting that Holdsworth was paired with monster guitarist Frank Gambale as part of shred impresario and Shrapnel Record’s founder Mike Varney’s MVP (Mark Varney Project). The 1990 album was entitled Truth in Shredding, and both axemen were instructed to play solos at least three minutes long. They jammed on a diverse set of fusion classics from Michael Brecker’s “Not Ethiopia” to Wayne Shorter’s “Ana Maria.”

Although many categorize Holdsworth’s music as jazz, some purists found him inauthentic. Perhaps to prove them wrong, his 1996 album, None Too Soon, featured jazz standards, including Joe Henderson’s “Isotope,” Bill Evans’ “Very Early,” Django Reinhardt’s “Nuages,” and John Coltrane’s “Countdown.” The latter is an extremely challenging tune along the lines “Giant Steps” that jazz musicians use as a way to weed out lesser players. Interestingly, Holdsworth’s follow-up, 2000’s The Sixteen Men of Tain, featured originals but had more of a jazz sound than None Too Soon, thanks to its acoustic rhythm section and the addition of trumpeter Walt Fowler.

Jazz guitar superstar Kurt Rosenwinkel, a committed Holdsworth fan, invited Holdsworth to be his guest at the 2013 Eric Clapton Crossroads Festival at Madison Square Garden. Reached after Holdsworth’s death, Rosenwinkel observed, “The feeling of sharing the stage with my hero is something I will never forget, a dream come true. We had some good laughs. He joked about his girlfriend telling him to get a real job instead of wiggling his fingers all day. Allan’s contribution to music and the guitar can’t be overstated. Even beyond the sophistication of his harmonic language and the unbelievable things he achieved on the instrument, which are unparalleled, it is the soulfulness—the depth and staggering melodic beauty.”

In addition to his original sound, Holdsworth had a unique perspective on gear. Early on, he carved up a Strat to fit a humbucking pickup and, in part, helped usher in the era of the Superstrat. His guitars often featured a sole bridge pickup, because he felt that more magnets from another pickup would pull on the strings and deaden vibrations. He also loved flat-radius fretboards and idealized a guitar with a Fender scale length, for its tight bass response, but with Gibson-style string spacing.

His first good electric was a Fender Strat, which he loved, but later traded for an SG that he used until joining Tony Williams’ band. In the early ’80s, he used signature Charvel and Ibanez axes before coming across the Steinberger TransTrem-equipped GL headless guitar. Later years saw him working with esteemed luthiers like Bill DeLap and Rick Canton on headless guitars. Holdsworth also collaborated with Kiesel (previously named Carvin) on a signature model called the Fatboy, which was semi-hollow with a headstock. At Winter NAMM 2012, Kiesel unveiled headless versions of another Holdsworth signature model.

Holdsworth also made extensive use of the SynthAxe, a MIDI controller shaped like a guitar, notably on Atavachron, Sand, and Secrets from 1986 to 1989. He also helped create Yamaha’s UD-Stomp, an effects box capable of eight lines of simultaneous, modulated delays. The UD-Stomp allowed him to get his atmospheric, volume-swelled sounds without having to lug around racks of gear. He later adopted Yamaha’s more compact Magicstomp, a multi-effects unit that offered UD-Stomp patches, and used six Magicstomps chained together onstage. Two were for his clean sound, two for his lead sound, and two were either for backups or for special effects, like a ring modulator or Leslie.

Holdsworth was an uncompromising visionary who set impossibly high standards. It’s no surprise that, while his playing made guitar geeks worldwide want to quit, he was almost never satisfied with his performances and took painfully long periods to finish recordings. His most recent studio album was 2001’s Flat Tire: Music for a Non-Existent Movie. Earlier this month, a 12-CD box set collecting his solo albums and a live concert, justifiably titled The Man Who Changed Guitar Forever, was released, along with a double-CD best-of collection curated by Holdsworth called Eidolon. In a now-eerie bit of foreshadowing, that title is an ancient Greek term for “ghost.”

Special thanks to Allan Holdsworth authority Chip Flynn for help with this story.

YouTube It

Attempting to learn Allan Holdsworth’s “Devil Take the Hindmost,” from the album Metal Fatigue, became a rite of passage for ambitious fusion guitar players. Here in Tokyo, he performs the song with his I.O.U. band in 1984, the year before the album was released.