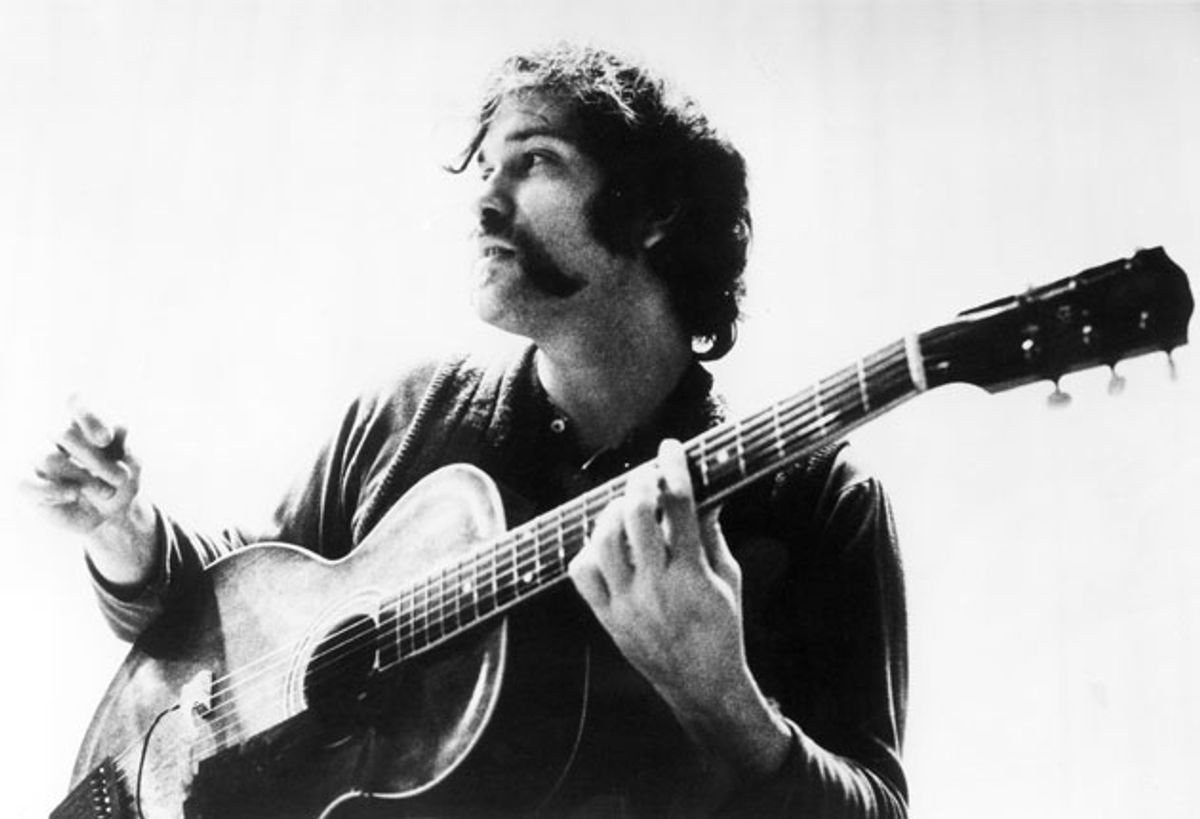

Nels Cline remembers the great guitarist and composer who had a profound and lasting impact on ’70s fusion and contemporary jazz improvisation.

Had I not already heard that the great guitarist and composer John Abercrombie was seriously ill, I would be walking around in a state of total emotional devastation today, the day following news of his death from heart failure on August 22, 2017. The extent to which his music and playing touched me is—like most aesthetic discussions/descriptions, I suppose—hard to put into words. John had recently released Up and Coming on ECM, the label on which his presence in the 1970s was nearly ubiquitous and had much to do with steering its aesthetic direction. To my ears, there was no clue in the music that this brilliant artist was in serious and sudden decline.

I first heard John Abercrombie in the early ’70s on a record by Barry Miles called Scatbird (released in 1972 on the Mainstream label), which may actually have been his first recording to officially emerge. I heard this thick Les Paul tone with a phase shifter playing lines that sounded like the guitarist had spent some serious time listening to John McLaughlin. I was interested but not galvanized, but the decade was young. Not long after this he ended up playing in the Billy Cobham Crosswinds band, and this was a time when Paganini-like virtuosity was the gestalt. John always sounded like he could do that, but I now realize that his gifts, as they emerged only a few years later, had more to do with a combination of his mastery of a very personal jazz syntax and an ability to morph into various odd and wonderfully musical personalities.

Around this time, a huge chunk of my world revolved around my almost obsessive love of Ralph Towner’s playing and compositions. It was Ralph who gave it to me straight when I, in a casual backstage conversation during the ECM Festival at UCLA in 1976 or ’77, expressed mild surprise that he and John were starting to play as a duo. In my aging memory, Ralph actually became almost stern with me when he said something like, “You have to love Abercrombie. His playing is completely fresh and filled not just with character but with characters.” Somewhat stunned, I immediately reassessed. I had just heard him with Jack DeJohnette’s New Directions and really loved how he used a Les Paul Junior to punctuate the open-ended music with cogent stabs and runs. It was a sound that ended up influencing me and how I sometimes approach comping chords in freer situations.

At this point, John began to appear on dozens of ECM recordings. His first record under his own name was Timeless with Jan Hammer and Jack DeJohnette. It has been acknowledged as a stone classic for decades, not just by virtue of the scorching playing it evinces at times, but also by virtue of John’s brilliant composing. Not much later, his record of overdubbed guitar music called Characters was released (please note what Ralph Towner said to me in the previous paragraph), and along with the subsequent duo recordings with Towner, it had an effect on me and my musical thinking that was utterly profound. John’s playing goes far beyond showing off chops and merely showcasing his abilities. It reveals varying voices, like someone telling you a story but not being afraid to change his voice to say different characters’ lines to make the story come alive. He also did dozens of ECM sessions. One that really sticks in my head right now for some reason is the Jan Garbarek album Eventyr, on which John adds so much vibe on his guitar and electric mandolin. DeJohnette’s Pictures album has also just floated into my head, a record of only the two of them with a minimal, almost ambient quality. Then there was Gateway, a kind of supergroup with DeJohnette, Dave Holland, and John playing an SG or Melody Maker or something and liberally using the tremolo bar and volume pedal to an almost eccentric degree. That sound seeped into my consciousness, changed my style, and necessitated my purchase of a volume pedal.

I would linger around neurotically whenever John and Ralph would play in Southern California, and John was always really friendly and really funny. He and Ralph were so sympatico and seemed to share a similarly wry and sometimes dark sense of humor. John always reminded me of the brilliant but rumpled professor or detective, ready with an acerbic comment or self-deprecating shrug, his thinning hair in a random swirl of some sort. I heard the John Abercrombie Quartet (with Richie Beirach, George Mraz, and Peter Donald) several times at The Lighthouse in Hermosa Beach. One stormy Tuesday night my brother and I saw them play to 30, maybe 15, people. From the first note the group was on fire.

As time went on, John threw away his pick, concentrated on using his thumb, and headed in a more “straight-ahead” jazz direction. He continued to write beautiful songs and make great records. As I look over my collection, I see the wonderful album he made with John Scofield on Palo Alto Jazz, the duo record with Don Thompson, all his ECM releases. It is because of John, and to a slightly lesser extent Bill Evans, that I play “Beautiful Love” on my Lovers album. It’s because of him I learned that the song first appeared in The Mummy with Boris Karloff.

The last time I saw John was in Melbourne during a jazz festival. His quartet with Mark Feldman, Drew Gress, and Joey Baron was performing. I ran into him on the steps outside our hotel, almost literally, since we didn’t see one another until we were practically face to face. He was as warm and funny and sweet and rumpled as ever. It’s so hard to imagine him ill and suffering, so hard to imagine this planet and our collective musical life without him. My friend Brian Camelio sent out an email to a bunch of guitarists several weeks ago telling us how ill John was and that we should send cards to try to cheer him up, which I did. I had no clue that things were so dire. But as such the news of his death is not as much of a shock to me as it could have been, and I am grateful for this.

Even as tears are forming in my eyes right now, they may have otherwise have become an unmanageable torrent. May we all appreciate every blessed moment we are able to breathe and live our lives. And may we all take a moment or a day or the rest of our lives to reflect on the beauty and wonder that is John Abercrombie.

Me, I think I will put on the ultra-poignant opening track from Up and Coming called “Joy” now and let it all out.