The guitar legend keeps his classic sound and style close to the bone on his new Baby, Please Come Home, fortifying his reputation with his beloved Strats, ’59 Bassman reissues, and hotel room keys.

Jimmie Vaughan has always been a 6-string badass—at least since he started playing dances and bars as a teenager in mid-’60s Texas, where he rapidly became the guitar player all the other young guitarists in the Lone Star State aspired to match in tone and technique. Over the past half-century, his big, bold, perfectly chiseled sound and Zen phrasing have grown richer, making him a legend everywhere the language of guitar is spoken. Although his brother, the late Stevie Ray Vaughan, played in a dialect closer to Albert King’s and Jimi Hendrix’s, Stevie’s main guitar idol—from the short-pants days when they strummed acoustic guitars together on their parents’ front porch in Dallas until Stevie’s tragic death in a helicopter accident after a 1990 concert in Wisconsin—was Jimmie.

Jimmie broke out of Texas in the ’70s with the Fabulous Thunderbirds, with ceaseless get-in-the-van tours and a series of albums that balanced original tunes with numbers penned by relatively forgotten blues and R&B artists like Jerry McCain, Slim Harpo, Jimmy Mullins, and Frankie Lee Sims. The T-Birds and Stevie were at the forefront of an ’80s old-school blues revival, performing with a rock-infused vitality that injected life into a genre that had fallen from the mainstream’s radar. In 1986, the T-birds even had a top 10 hit—their original tune “Tuff Enuff”—while Stevie was becoming an arena headliner. At the time, an array of classic blues artists, including B.B. King, Etta James, and Buddy Guy, all credited the Vaughans’ success with boosting their genre and their careers.

That wasn’t intentional. The Vaughan boys just wanted to play the music they loved and spread its positive vibes. And they found a way to do that together once more with 1990’s Family Style, which united Jimmie and Stevie in the studio with producer Nile Rodgers. Sadly, Stevie died a little less than a month before its release, and, understandably, Jimmie went into an emotional tailspin. He quit the Thunderbirds and withdrew from the spotlight, resurfacing four years later with his first solo album, Strange Pleasure. He’s made seven more albums since, including a duo recording with singer-guitarist Omar Kent Dykes. While each one has captured his corpulent tone and impeccable playing, the four albums he’s made since 2010—that year’s Plays Blues, Ballads & Favorites, 2011’s Plays More Blues, Ballads & Favorites, a 2017 live set, and the brand-new Baby, Please Come Home—sound closer to the bone. Or, at least, to the sturdy skeleton of ’50s and early ’60s blues and roadhouse R&B that makes Vaughan’s music stand tall.

Vaughan insists that he’s not on any kind of mission to preserve the songs and sounds of that era, and yet the songwriting credits on Baby, Please Come Home read like it was compiled by a cognoscente of the period when raw blues was ramping up to rock ’n’ roll, and the two mixed blood: Bill Doggett’s “Hold It,” Etta James’ “Be My Lovey Dovey,” and tunes by Clarence “Gatemouth” Brown, Dave Bartholomew, Richard Berry, Fats Domino, and even hillbilly hero Lefty Frizzell. Vaughan is that cognoscente, of course, but he’s also a superb interpreter and master of the styles and sounds captured on the original vinyl he treasures.

Sure, his chiming, sliding chords, precise bends, and sticky single-note lines reflect the careful digestion of the playing of dozens of influences, from B.B. King and Freddie King to Johnny “Guitar” Watson, but they also telegraph what’s commonly described as soul … which is really an honest and open expression of character. Vaughan sounds only like Vaughan, regardless of who or what he’s channeling. He literally is his music—and in the years since Family Style, where he made his singing debut, his voice has also become a potent part of that expression. On Baby, Please Come Home, it’s out front with minimal reverb, with all the dust accumulated from his beginnings in Texas saloons to the stages of Clapton’s Crossroads Guitar Festivals, providing the same patina of experience that made the work of his own heroes so memorable.

Vaughan was on a tour stop in Solana Beach, California, when we spoke by phone. He was gregarious and laughing about various ticks in the music he plays and loves. And the conversation ricocheted between the past and present: from guitars and amps to his personal Top 40 to how he conjures and sculpts his sound to his little brother, Stevie. The last time I spoke with Vaughan, it was about his guitar collection, and he’d just acquired one of his holy grail guitars, so we started there.

Do you still have that killer ’50s Barney Kessel Kay with the Kelvinator headstock?

Yes. It’s one of my favorite things. I heard that Barney Kessel, who is one of my favorite guitar players, didn’t like it. I can kinda understand that. You like what you like, you know. And you can have five guitars that look the same, but one of ’em’s gonna work and the other four won’t.Some of them can speak to you and bark better, you know what I mean?

Are you still adding to your collection?

Well, I bought an L-5. I forget what the model is, but it’s got a pointy cutaway and it’s with humbuckers. I bought it from Rudy [Pensa, of Rudy’s Music] up in New York. It’s a jazz guitar. And I have a couple of those. I bought, like, a T-Bone Walker Gibson—the one that he played with the three pickups. And then I have my new guitars I’ve been playing. So I’m guitar-happy.My wife told me that. I said, “Honey, do you want to go buy you some shoes?” And she said, “No, I’m shoe-happy right now.” [Laughter.] So I guess I’m guitar-happy.

TIDBIT: Vaughan recorded all but his vocal performances for his new album live on the floor at Fire Station Studios in San Marcos, Texas, where he ran two ’59 Bassman combo reissues and played his new Fender Custom Shop signature Stratocaster and a Japan-made guitar of unknown pedigree.

Just before putting on Baby, Please Come Home, I was listening to a 1950s Ike Turner & His Kings of Rhythm collection called She Made My Blood Run Cold, and it struck me how much, aside from the fidelity, your album sounds like it. The overall sound, the guitar approach and pace … they could’ve been recorded at the same time. How important is it to you to achieve that sense of period authenticity in arrangements and sound?

Well, I don’t really do it for that reason. I do it because I think it sounds good like that. I’m not trying to be correct. I’m just trying to get that sound. Basically, it’s live in the studio.We might need two or three takes, but after a couple or three, you kinda want to go to something else because it gets old. We used this place in San Marcos that I’ve used many, many times. It’s an old fire station [Fire Station Studios], and even the T-Birds recorded there. It’s just a nice big room, and they have nice equipment.

Your recent albums focus on nuggets from the pre-rock or early-rock catalog of blues and R&B. Might you be on a mission to give those songs and that era a new life for a new audience?

I don’t have any big, fancy reasons to do it except that’s what I like, and it seems to me the most satisfying just to make records that you like. And I’ve found all these players that really do it right.I pick songs that I think I can sing. It’s a little bit more like picking a pastry that you like. I don’t get into a big philosophy about it. I don’t know how much influence I can have on the world anyway, so what if we all just do what we do and hope that everything turns out okay? [Laughs.] I’m not trying to save the blues or any of that. I think if you really enjoy something, then it will come through and other people might get it.

It’s the art. It’s like, you have a canvas and you have paint, so what do you want to paint? It’s mostly artists that I remember from my childhood. And I sort of have my own Top 40. I’ve done that since I started, because it just seemed like it was more fun. I can’t imagine being in a group and playing songs that you don’t like. I’ve tried that, and it wasn’t good. So I guess I hardened against anything like that. Now, for me, it should be all fun.

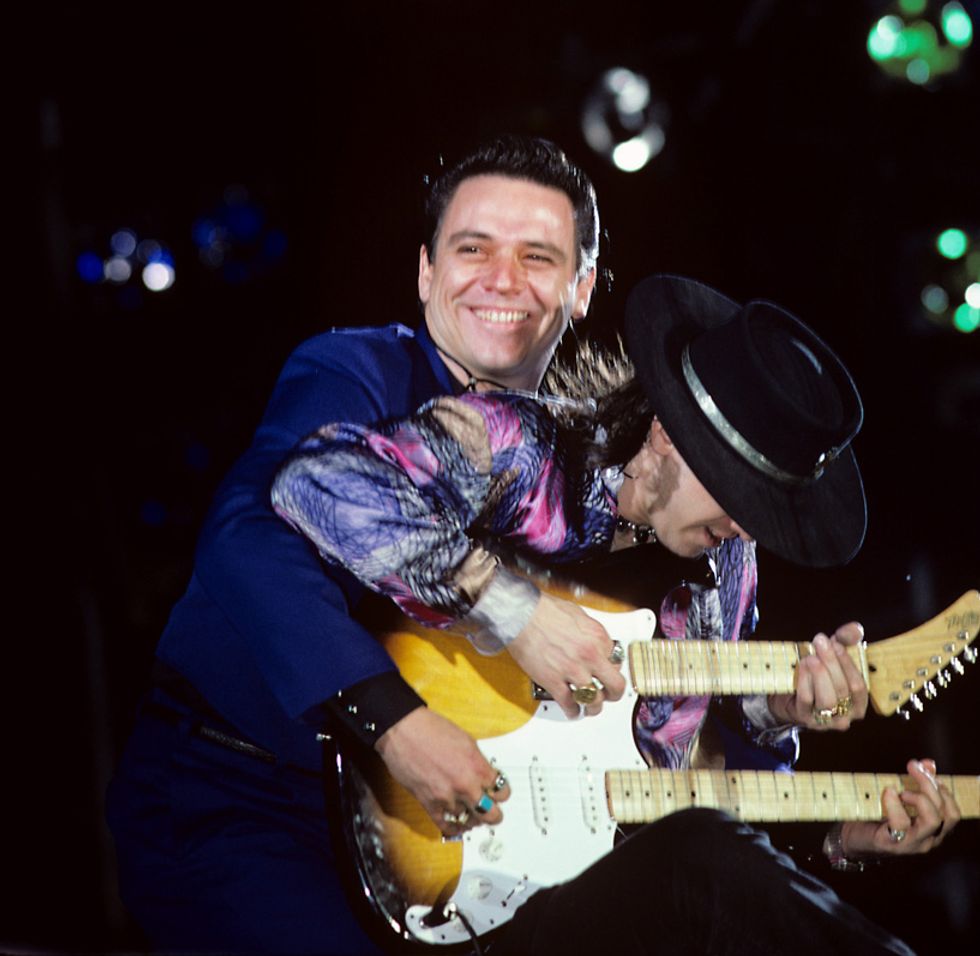

As boys, Jimmie and Stevie Ray would play for their parents’ friends. Jimmie recalls, “The guest would go, ‘You boys are pretty good. Maybe someday you can make a record together.’ And so it had always been planted in our heads that we were gonna make a record together someday.” That album was 1990’s Family Style. Photo by Ebet Roberts

Who would be a couple of the artists in, let’s say, the top five or 10 of your personal Top 40?

Well, last week I listened to Segovia all week. Now, I can’t play like Segovia, and I don’t know anything about him, but I’m a fan, you know? I like hillbilly records, too. I like Webb Pierce and all kinds of stuff from the ’50s. I like jazz. It doesn’t have to be from the ’50s, but I find that era is more interesting for me. It’s fun, it sounds great, and what an exciting time, musically speaking. Whenever I talk about all this stuff, I’m talking musically. Because I’m sure there’s always bad things happening in the world somewhere.

I love Albert King, B.B. King, Albert Collins, and, my favorite, I guess, would be Kenny Burrell. It’s a little bit like whoever’s on top of the record stack. Bill Doggett. And I just played several shows with Buddy Guy, who’s in his 80s, and he was tearin’ it up. They’re all great.

I met Burrell a couple of times, and what a great musician. I got to see him play about 30 years ago. My brother and I were playing in Hollywood, and we were staying at the Hyatt Regency … you know the one they call the Riot? Which is on Sunset Boulevard across the street from what used to be the Mondrian. Anyway, we were staying at the Hyatt, and we came home late at night after our gig, and, in the elevator, there was Kenny Burrell, standing there with his laundry. And our mouths dropped open, and we said, “Kenny Burrell!” [Laughter.] And we didn’t even know what to say to him, but he was just doing his laundry, and he was staying there because he was playing there. It was unbelievable. That’s the same place that Little Richard used to stay on the top floor.

If you’d volunteered to do his laundry, you might have made a friend for life! When I hear your name, the first thing I think about is your tone. It’s so bold and distinctive. What set you on the path of your sound?

I like it to sound like it’s gonna blow up, but it’s very clean, if that makes sense. I like to turn the amp up really loud and turn the guitar down to find that sweet spot. And I love it when maybe it’s a little bit too trebly, and the presence is up loud. I guess it’s a sound I heard on those old records, and I just went for it.

How did you get your core tone for Baby, Please Come Home?

I have a couple Bassman amps—they’re reissues. My engineer on this record went into them and put Marshall treble caps at the beginning, and it just made them great. It’s a little bit like there’s a treble booster or something. It kinda put them over the top—where you just touch it, and it’s not distorted, but it’s like that blow-up sound I was telling you about.If you’ve got an amp that’s doing what you want, any three of those Strat pickups sound great, or in between. And I wire everything backwards and different. I’m always fooling around with stuff. We reverse a couple of wires here and there, and then you have the…. It sounds more like a Gretsch than your regular Strat in-between.

It’s a combination of getting the right amp and getting in a room that’s got a great sound, and putting the mics in the right spot. It’s not close-miked. It’s always that room sound, and multiple mics, and I usually end up using whichever one sounds the best.

And are your Bassman amps heads or combos?

The 4x10s, you know. The classics. I’ve had Matchless amps for years and years. I had a 4x10 and then I had a 4x12 tall combo, and then I had a 4x12 and a head, and I loved those a lot, and I wore them out. And then the company went out [in 1998, before its 2000 comeback], and I couldn’t get those exact components, so when I had them fixed, they changed. So I started fooling around with Fenders again, and that’s when the ’59 Bassman came out, and it’s hard to beat those.

On “Hold It,” on the new album, there’s an entirely different sound, and I was wondering if you had the treble rolled back on the Stratocaster.

Well, it’s not a Stratocaster. It’s a Coronado copy. It’s Japanese. I bought it for $200 on eBay and spent more than that trying to fix it up. It’s a bolt-on neck, and I bought it because I liked the pickups. They’re amazing single-coil pickups. But it’s a really cheap guitar and it doesn’t have a name on it, so I don’t really know what it is.And that’s through a Bassman.

You don’t use pedals, do you?

No. Well … tremolo. Strymon Flint—the black one that has three tremolos and three reverbs. I would recommend anybody that’s into tremolo and reverb try that. There’s nothing like getting that good tremolo where it kinda goes up and down a little bit. They have sort of the Lonnie Mack sound.

Almost that Magnatone thing?

Almost a “vibrola?” I don’t know what they call it. The tremolos are the three different kinds that Fender had back in the day.

What guitars do you use altogether on the album? I assume your new Fender Custom Shop Strat is on there.

I have the new ones from the Custom Shop. I used my white one and my sunburst one.I love these guitars. They’re set up like my old one, with the same pickups and wiring that I came up with trying new parts on my own guitar. The great thing about Fenders is that they’re like ’34 Fords. You get a couple of Fenders, and you can swap out or put new necks on ’em, or pickups. I love Stratocasters better than anything. I love Telecasters, too, but there’s something about a Stratocaster. I don’t think they’ve ever come up with anything better than that.

Guitars

Fender Custom Shop 30th Anniversary Jimmie Vaughan Signature Stratocaster

Unknown brand Japan-made Coronado-style

Amps

’59 Fender Bassman reissue (two)

Effects

Strymon Flint

Strings and Picks

Hand-cut plastic hotel room keys or Fender mediums

D’Addario and Fender hybrids (.0105–.054)

What first inspired you to pick up a Strat?

Seeing Buddy Holly. And then I’ve seen pictures of B.B. King playing a Stratocaster in the ’50s, which is on a lot of those old B.B. King records. Of course, Buddy Guy.

So, on Baby, Please Come Home we’re hearing that new Custom Shop Strat and hearing this Coronado imitation from Japan. Anything else, guitar-wise?

Nope, that’s it.And I had the two Bassman amps. It’s about getting into the room and getting the mics in the right place, to where it doesn’t sound too close or too far away.

Are you still playing flatwound strings?

Absolutely. They don’t make a set that I like, so I use the .0105s on the little E string. Then a .014, a .017, and then a .028 on down. And sometimes I’ll put a .054 on the bottom, because you can tune them down. With a flatwound, you can have a bigger string and get that thud that really works good with a bright sound. And I have an unwound third.

What kind of picks do you use?

Well, you’re not gonna believe this, but I use my hotel keys and I cut them to shape.I make a point. I like a point on the end. And even when I use my Fender mediums, which I also like, I cut them to a point, so I have that “click,” you know?You can get so many different sounds, just with the tip and the thickness of the pick— like with how far down you hold the pick, so the amount of “flop” is controlled. Especially with flatwounds.

How did you find out that plastic hotel keys would be good for picks?

[Laughs.] I just was experimenting and I thought, “Well, I’ll try it out on this hotel key,” and darn if it didn’t work good! And then I thought, “Gosh, I’m on the road all the time. I can save all my hotel keys.” You don’t want to turn them in—don’t tell the hotel that [laughs]—because I think they just throw them away, anyway.When the world comes to an end, I’m gonna have a lot of guitar picks when nobody else will!

Why did you switch from roundwound to flatwound strings?

Well, I got an ES-350, and somebody told me to put flatwounds on it, and I did. It was a jazz guy. I remembered flatwounds from when I was a kid, and after a couple of dates, they started sounding better and better and better. So I thought I should put some on my Stratocaster. And the next thought was, “No, that would be terrible, that would be sacrilegious!” And I finally did it anyway. I just fell in love with it. So I found out that that’s the sound that I was trying to get all those years, when I was listening to those old records. I talked to Steve Cropper, and I said, “Steve, you had flatwounds on ‘Green Onions,’ didn’t you?” And he said, “Yes.” I bet Chuck Berry had flatwounds, too, when he did all those great records.I think it’s something that everybody forgot. In the ’50s, when you bought a Telecaster or a Nocaster, they came with flatwounds.

So my wound strings are flatwounds. I’m hooked. When the T-Birds would be out for three months or something, we’d play every night, and my fingers would be just tore up. I’d have big callouses; I could still do it. But my fingers now are smooth and tough, and I can go out and play every night, for as many nights as I want, and my fingers don’t get tore up. And they’re not sore, either. I’ve been using flatwounds for about 10 years.

Stratocaster lover Jimmie Vaughan has always dressed every bit as bold and sharp as his tone. Here, he plays the Strat that launched the Jimmie Vaughan signature model line, in concert with the Fabulous Thunderbirds at the Capitol Theatre in Passaic, New Jersey, in April 1986. “I don’t think they’ve ever come up with anything better than that,” he says of the iconic model. Photo by Ebet Roberts

One of the things I love about your playing is that it has this kinda slow, almost sticky, behind-the-beat thing. You can obviously play fast when you want to, but it seems like you rarely want to. Is that slow, grooving approach a stylistic or emotional decision?

When I started playing, I wanted to be fast. I mean, there were a lot of fast guitar players. So I learned all the pull-offs and the diddle-diddle-diddle and all the different things you could do, and after I figured it out, I realized, well, it’s just exercise. It’s just a trick. Anybody can learn how to do that if they want to. It’s not magic. So I started listening to sax players and other musicians that I enjoyed—what they emphasized—and I decided I wanted to play something that means something. I want to have that as a goal, as opposed to just doodling around.

That was also one of the first things that intrigued me about blues and jazz guitar. I used to put on a Freddie King album, and I thought, “How does Freddie King know what he’s going to play on the solo? How does he know? Where does he come up with that?” I was so intrigued I began asking myself, “what is that all about?” I’d listen to Lonnie Mack, and it was like, man, he’s playing riffs every verse. And he’s topping himself as he comes back and does the head at the end. So all that stuff was fascinating, and I would also listen to sax players or steel-guitar players or anybody that was trying to play music—as opposed to just diddlin’ around. It seems like there’s a lot of diddling going on in guitar. I just thought there was enough guys doing that already, and it didn’t really do anything for me.I’m talking about a goal. We want to have a goal. We’re trying to get there, and we never get there, and every once in a while we get lucky. That’s what it feels like.

And that’s one of the things that keeps us playing—those times when we get lucky.

Right. [Laughs.] Exactly.

It took you many years to step up to the microphone as a singer. What’s your relationship like with your voice?

When I was a kid, I had Muddy Waters records, and all these great singers, and when I sang, it sounded like a dumb little kid. So I didn’t sing for a long time, and then when we did Family Style, I was scared to sing. Nile Rodgers said, “Stevie’s gonna sing a couple of songs.” Then he looked at me and said, “Which songs are you gonna sing?” And I was like, “Uhhhh.” I didn’t have an answer, and so I had to either sing or go home, which was basically how I felt. So I said, “Well, I’m gonna have to sing now.” Most everybody can sing, and the goal is just to be your own voice. Express yourself. It’s not as scary and lofty as thinking about Brook Benton or Sam Cooke or Muddy Waters or some of these amazing singers that we’ve had.

So anyway, I just decided that I really needed to sing, and I wanted to, secretly, so I just had to go for it. It was more like jumping in the deep end and not knowing how to swim. You’re gonna float up to the top or swallow a bunch of water. It was a combination of desire, and I also had to do it.

A lot of times when you’re in the studio, you don’t really know the song that much. You’ve done it at rehearsal two or three times. But it happens both ways. My voice on “Be My Lovey Dovey” is not an overdub. But the other ones I sang a scratch vocal and then re-sang it.

When you left the Fabulous Thunderbirds, the band was still riding a wave from the hits “Tuff Enuff” and “Wrap It Up.” Why did you leave?

I really didn’t intend on leaving. I was just…. When I was a little kid, somebody would come over to the house and my father would say, “Jim, go get your guitar and come out here and play a song for Mr. So-and-So.” And so I’d play a little bit, and then Stevie, four years younger than me, he started coming to play, too. He would bring his toy guitar, which was one of those cowboy things, not a real guitar.

And then, over the years, we would play a song together on the acoustic, and the guest would go, “You boys are pretty good. Maybe someday you can make a record together.” And so it had always been planted in our heads that we were gonna make a record together someday. So Tony Martell from Epic Records called Stevie after Stevie had won his first Grammy. I can’t remember what record it was.

Was that for In Step?

I think that was it. That was his first big record, I think. Anyway, he did that record, and then Tony Martell said, “You guys should make a record together. We would really be into that.” So we started talking about it, and then we finally did it, and then Stevie got killed right before it came out. Then we had this situation. I said, “We can’t put a record out now.” Because, you know, it was all so new and fresh and unbelievable and crazy and weird, and what do you do? Epic said, “Well, I think it’s better to put it out than not put it out.” And I was like, “okay, okay.” But I said, “I’m not gonna go play any gigs, I can’t do that. It’s too weird.”

The whole thing.… We made the record, and then three months later, before it came out, Stevie got killed up there in Wisconsin. And I was up there with him. He called me and said, “You gotta come up here. Buddy Guy’s gonna be here. Eric’s gonna be here. And we’re all gonna play.” And he said, “You come up, too.” So I went up there, and he gets killed. Then, I couldn’t go out in public. It was too weird, because everybody wants to tell me how sorry they were that Stevie was dead, and I didn’t know how to … I just didn’t know what to do. So I just had to go hide for a while. It was so tragic and sad that I just didn’t know what to do.

There wasn’t anything I could do, and you know, Stevie, when I was a kid, it was my job to get Stevie to the bus stop and get him to school and get him home, because I was his big brother. And so, it felt like I didn’t do good. Even though there wasn’t anything I could have done about it. It just fucked everything up. I didn’t know how to act or what to do. I just had to go grieve. And plus, then the record came out, and then everybody wanted to hear the record because the story of … you know what I mean.

Yeah, I know. It’s really, really a lot to process.

I didn’t know how to handle it all.

You know what I probably figured out? About a year or so ago, the Grammy museum had that display [Pride & Joy: The Texas Blues of Stevie Ray Vaughan], and they brought it to Texas, and they had all of Stevie’s guitars, or a lot of them. And I was involved. I got his stuff. Then, it occurred to me: I’m not gonna get over this. I’m pissed off, and maybe that’s the way it’s gonna stay. Because when something terrible happens, you have a desire to deal with it, and you try to figure out how to deal with it, because you have to go on living. I had relatives, I had my mother, and my kids. After it happened, people were looking at me to see how I was going to act, you know? If you can handle it, or not handle it, it’s gonna affect them. It was all that kind of grown-up stuff. The thing is, Stevie never got to have a family or kids. And you know he’s a fabulous musician, but he was my little brother, so I’m thinking about my little brother.

In a nutshell, to answer your question about leaving the T-birds, I didn’t know what to do, and I didn’t want to go out on the road and ride in a van and answer questions. People would want.… You’d go to the grocery store and you buy some coffee. And, of course, you’re happy that you can go buy coffee, and you’re not dead. But while you’re over buying coffee, somebody comes up and they go, “Oh my god!!” and they start crying. In the grocery store! Because they all remember that day when Stevie got killed, but they … they didn’t really deal with it. So when they would see me, or if they would realize it’s me, it would bring it up, and they would start crying. So here’s two of us crying in the grocery store. That kind of weird stuff that you can’t really control or explain. I guess what it is, is just the normal time it takes to grieve about someone that you care about. And also, I’m sure there’s some survivor’s guilt … all that stuff.I don’t know how to explain it. I’m happy to be here. I have a wonderful life, and I get to play guitar every day.

Jimmie Vaughan taught a spontaneous masterclass in old-school tone and phrasing during a May 17, 2019, performance at the famed Dingwall’s in London. This video compiles some highlights, including, at 3:56, an exquisitely trebly tremolo-infused solo on Slim Harpo’s “Baby Scratch My Back,” followed by some chicken pickin’, as a nod to Harpo’s original version.