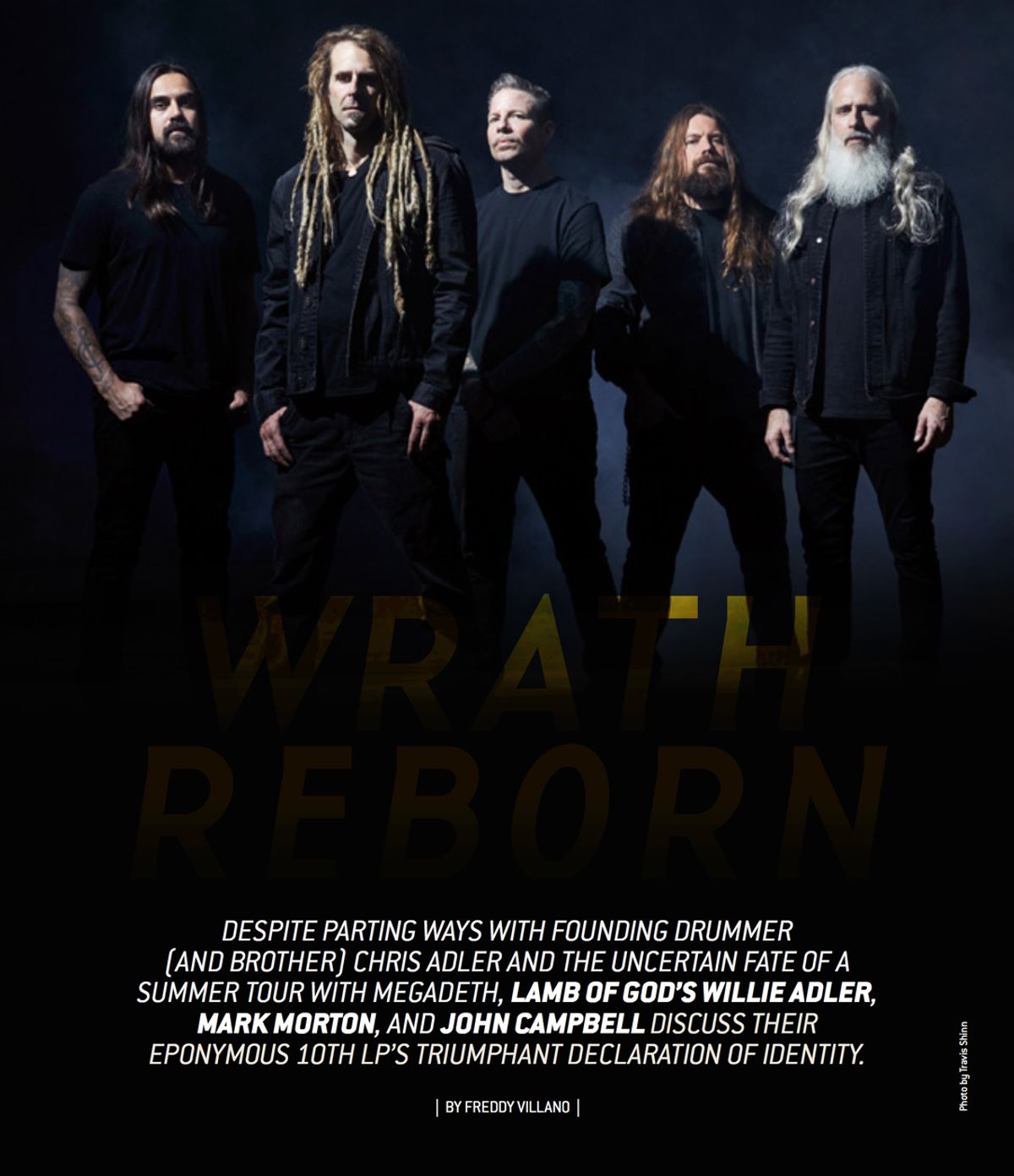

Despite parting ways with founding drummer (and brother) Chris Adler and the uncertain fate of a summer tour with Megadeth, the trio discusses their eponymous 10th LP’s triumphant declaration of identity.

When Lamb of God burst out of the gate in 2000 with New American Gospel, the Richmond, Virginia, quintet helped ignite a musical movement known as the New Wave of American Heavy Metal—a term rooted in the New Wave of British Heavy Metal appellation given to seminal bands like Iron Maiden, Motörhead, and Venom in the late 1970s and early ’80s.

That terminology signifies a return to elements of past influences with an emphasis on forging the future. In Lamb of God’s case, they were honoring the course originally charted by bands like Metallica, Slayer, and Pantera, who emerged during the early-’80s golden age of thrash. Up-tempo tunes, furious rhythms, wicked guitar riffs, and lyrics expressing disillusionment with cultural norms formed the template. But Lamb of God were also literally evolving a sub-genre of heavy metal, not just emulating one. And they were doing this by “balancing the equation of power, rage, tradition, and craft,” as music journalist Johnny Loftus astutely observed.

Lamb of God was formed in 1994 after guitarist Mark Morton, bassist John Campbell, and original drummer Chris Adler met at Virginia Commonwealth University. A few lineups later, they recruited vocalist Randy Blythe and released their eponymous 1999 debut under their original band moniker, Burn the Priest. When guitarist Abe Spear left and was replaced by Adler’s younger brother, Willie, the group renamed itself Lamb of God. They signed with Prosthetic Records in 2000 and released New American Gospel in September of that year.

The band toured incessantly, issued As the Palaces Burn, and joined the first MTV Headbanger’s Ball tour in 2003, and released Ashes of the Wake in 2004 on Epic Records. Lamb of God’s work ethic and a growing fan base earned them a second-stage slot on Ozzfest that year, too. Since then, they’ve released five albums, been nominated for a Grammy twice, and, in perhaps the ultimate acknowledgement of their influence on contemporary pop culture and the hard-rock and heavy-metal guitar canon, have been featured in several video games, including Guitar Hero II, Guitar Hero Smash Hits, and Rock Band.

The band’s newly released Lamb of God is its first in nearly five years. Once again produced by Josh Wilbur, who’s worked with the band since 2009’s Wrath, it is the first to include new drummer Art Cruz. The songs are fueled by familiar ingredients: indelibly articulate and ferocious guitar playing, incisive lyrics aimed at America’s current political climate, and a vocal delivery as guttural and connected as ever. If longtime fans had any concerns about the loss of Chris Adler’s skins-bashing prowess, they need not worry: The outfit’s unmatched ability to imbue its menacing beats with swagger remains a hypnotic force to be reckoned with.

“I’m real focused on the groove,” says Morton. “That’s always been my primary attraction to heavy metal, and that’s why I like hip-hop. It’s that visceral reaction—that groove that makes your head bob.”

Despite the familiar components that have come to define a Lamb of God album, this time an intentional focus on songcraft elevates the band’s game. From the invigorating opening anthem “Memento Mori” to the breakneck pummel of the closer, “On the Hook,” Lamb of God is a testament to the quintet’s unyielding commitment to thrash, groove, shred, and stripped-down aggression—but even more it’s the dedication to songwriting that makes it a bold declaration of identity and intent that is clearly of the moment.

“In the last five years, I have been far more focused on being a songwriter,” says Morton. “I am way more interested in writing a good song than I am in writing a dazzling acrobatic riff or coming up with some super-mind-blowing, jaw-dropping solo.”

We caught up with Adler and Morton at home in Richmond, where they were social distancing just like most folks around the globe. Unfortunately, they had recently called off Lamb of God’s European tour. “Everything right now is up in the air,” Adler explains. “We have our [already-scheduled] summer run with Megadeth, so we’re hoping that by then everything’s fucking calmed down, because that would be a hell of a blow.” Despite the downturn, both were amiable and upbeat—invested in discussing their craft and particularly aspects of songwriting, how they share guitar duties, the gear they secretly geek out on, and their early influences.

What was the writing process like for Lamb of God? How long were the song ideas incubating?

Mark Morton: Everyone always wants to know how long the riffs are being worked on. It’s hard to say, because there’s no organized way of cataloging that. Basically, Willie and I are always compiling song ideas. And Lamb of God songs always start with the guitar part. So, Willie and I both compile ideas and work on them at home, by ourselves, with our own little software programs on our laptops. That’s sort of a perpetual process. I can say with certainty that the first time Willie and I took those ideas [for the new album] and got together in a room with [longtime producer] Josh Wilbur was in October 2018. So, a year before we actually got into the studio to record the album, we were making what I would call official new-material demos.

How elaborate do your home demos tend to be—are you just throwing down riffs or are they pretty fleshed out?

Morton: They kind of vary, but typically I like to put drums on them, mainly because when I’m communicating the song idea, or the riff idea, I like for the snare pattern to be established. The upbeat/downbeat decision has so much to do with the groove and pulse of the riff that I need at least a snare. I’ll program the whole drum kit, but it’s mainly just for the sake of establishing the snare pattern so everyone involved can hear my idea of where the groove is—where the pulse is. There have been times when I brought a full demo of a song in with a bass line, a drum part, stereo guitars, the guitar solo, and me doing a scratch vocal, because I wrote lyrics for the song. So it can vary from that to just a guitar part isolated by itself. But usually we will put some drums on it, so it’s listenable and you get the vibe.

TIDBIT: For their latest, LOG returned to the studio with longtime producer Josh Wilbur. “He told me one time that a big part of producing is psychology,” says bassist John Campbell, “so I guess his manner of psychology works incredibly well with Lamb of God.”

That makes a lot of sense, considering the architecture of your riffs.

Morton: We’re such a groove-oriented band that those decisions—of whether the snare is on ones and threes or on twos and fours, or whether it’s mid-tempo, half-time, double time—are pretty paramount for the character of the song.

When you’re presenting an idea to the rest of the band—whether it’s fleshed-out or more modest—how attached are you to your ideas?

Morton: That’s a great question. Again, it varies, but sometimes you get attached. I think it’s a pretty universal term, but one we definitely throw around a lot is “demo-itis.” It’s when you’re so married to your original demo that you can’t even fathom this idea that someone might interpret it a different way, or might have an idea that is different or, gasp, better [laughs].

Willie Adler: I’ve gotten a lot better about letting go of all that. There’s definitely an aspect of, “these are my babies, and I spent so much time on them,” but over the years we’ve grown to understand what makes a great song, which is 100 percent all of our ideas mixing together as one—or at least me and Mark getting together and playing off of each other. Those are always the best tunes. I mean, sometimes I can be really glued to it. I’ll be like, “How can you not like that?” [laughs], and they’re like, “Well, let’s just try this.” Everybody’s real cool about it.

Morton: So, it can kind of bounce around. But to your original question, sometimes it can be an exercise in humility to let go of what you originally envisioned, particularly when it’s for somebody else’s part. But I think Willie and I, who are usually the guys bringing this stuff in, are constantly aware that John Campbell is almost always going to write a better bass line than we might. And no matter how long I spend programming drums, Art Cruz is going to slay it when he sits down behind the kit.

What is your preferred DAW for your demos?

Morton: Nowadays, I’m using Logic. But I used GarageBand forever, honestly.

Adler: I’m using Cubase—Steinberg guy. Ever since I was introduced to having a DAW, and the technology of music production at home, that’s what I’ve been using.

Morton: I’ll tell you a secret that maybe I’ll regret [laughs]. There was a period when I was writing a lot of songs with static tempos because I was writing on GarageBand and you couldn’t change the damn BPM. So I was writing these demos, and I got used to hearing them at a static tempo, and that’s kind of how the song went. And, of course, in production we’ll play with tempos, but sometimes I just got so used to hearing it that way that that’s just what it was. I’m on Logic now, so that’s no longer containing me. Logic is cool, but at the end of the day, when we do the albums, it’s Pro Tools.

In the studio and onstage, Adler (right, with his signature ESP Warbird) and Morton take a tag-team approach, trading off on leads and rhythm guitar according to the demands of each song. Photo by Bill Hall

Being that you both write riffs, how do you split guitar duties?

Adler: We kind of go back and forth, depending on the song. If it’s a song that’s the majority of one dude or the other, they kind of take the lead. This time around it was really cool because we were all in the studio at the same time, so Mark was there when I was tracking my bits, and I was there while he was tracking, and it allowed us to just elaborate on ideas and, in real time, be like, “That’s awesome. I hear this other part going on right now, while you’re doing that.” And then it’s like, “Okay, let’s lay it down.”

Morton: Willie doesn’t do a lot of solos. He’ll do what I would call leads—single-note stuff, melody patterns, and that kind of thing. Most of the traditional soloing is me.

Adler: I would say that Mark is far more versed in writing and playing solos, for sure, whereas I’m definitely more riff-oriented, but that’s not to say Mark isn’t. So, I guess in a very black-and-white sense, Mark does the solos and I play the rhythms, but it’s much more dynamic than that.

There are a lot of other intricate things happening in your music, too, in terms of harmonies and melodies.

Adler: One-hundred percent—and just basic songcraft and structure. I mean, I can think of a part as a bridge, and Mark could hear it as an intro. So those are the dynamics that make interacting really cool. [When he plays something] he’ll allow me to hear it, basically, for the first time again and envision it as something different—and vice versa.

Morton: I tell people all the time, even if you are the lead guitar player—unless you’re Tony MacAlpine, or Vinnie Moore, or Paul Gilbert, or some cat like that—you’re playing rhythm 90 percent of the time, so you better have some rhythm chops first.

Do you focus on different elements of rhythm playing when you’re in the studio— like how a song might be recorded versus playing it live?

Morton: Yeah, you play differently. I have a pretty heavy right hand, so sometimes I will be coached by Josh to dial that back. He’ll say something like, “As cool as that is, it’s not tracking the same way as if you lightened up. So split the difference for me. I still want to feel that built-in swell and compression you have in your right hand, but tone it back to 2 or 3 out of 10 so it tracks right for me—so it’s not clipping or bending slightly sharp.”

Are you and Willie both playing rhythm on all songs in the studio, or do you ever—for the sake of recording something tightly—have just one person play the rhythm guitar part?

Morton: It’s all over the map. Of course, there are stereo left and right rhythms. Sometimes the right side is me and the left side is Willie. Or sometimes the verse will be left-and-right Willie, but the chorus will be left-and-right me. And then there are instances where, for the whole song, all the rhythm tracks are one of us. It just depends on the type of song and the strong points of the player. If there’s a lot of string skipping, galloping, and very precise, light-touch kind of stuff, that’s Willie. He’s a very, very precise player. He’s very accurate, and he just dances around the strings and around the neck in a way that’s very acrobatic and very technical. But he also has this obscure approach to note choice that’s not very conventional or traditional. A lot of his note choices and his patterns aren’t rooted in what one would call the “normal” scales. Some of the more powerful, real heavy, super-groovy, cadency stuff is me, because—I consider it ham-fisted—I just have a more powerful right-hand attack.

Willie, do you have any tips for playing such complex rhythms so tightly?

Adler: I hate to sound cliché and just say, “practice,” but I was never really taught properly how to hold a pick—or how to do anything, really. I wanted to play what I wanted to hear, and I wanted it to be clean, and I wanted it to be heavy, and I wanted it to be saturated. So, as far as my picking style, it’s hard to put into words exactly, because that’s all I know. It is a hyper-focus that I have. If I’m chugging along, I’m making sure that those chugs or triplets are super clean, and I’m not hitting any of the other strings. I guess that could play into my picking style, where my hand is all fucked-up-looking, and my fingers, on my right hand, aren’t necessarily anchored or holding on to anything. I’m just really trying to focus on that tightness and not having the ambient string noise going on.

How did you two track your guitar parts for this album?

Morton: This time, rather than having Willie’s setup and my setup, and recording them separately, we basically ran something similar to Willie’s live rig and something similar to my live rig, simultaneously and in stereo, and then blended them into each track. So each left and each right is a blend of Willie’s sound and my sound. My sound is a little more mid-pushed, Willie’s is a little more mid-swept, and he’s got a little more gain than I do. I’m a little cleaner, in terms of the gain structure.

Guitars

Jackson X Series Signature Mark Morton Dominion models

Amps

Mesa/Boogie Royal Atlantic RA-100

Mesa/Boogie Mark IV

Mesa/Boogie Mark V

Mesa/Boogie Rectifier 4x12 cabs

Effects

dbx 266XL compressor/gate

MXR GT-OD

MXR Phase 90

MXR Carbon Copy Analog Delay

MXR Custom Shop Il Torino Overdrive

Strings and Picks

Dunlop .010–.048 sets

Dunlop Tortex 1.14 mm picks

Guitars

ESP Will Adler Signature Series Warbird

Amps

Mesa/Boogie Mark V

Mesa/Boogie Triple Crown

Mesa/Boogie Mark IV

Mesa/Boogie Rectifier 4x12 cabs

Effects

Mesa/Boogie Five-Band Graphic EQ

Strings and Picks

SIT Will Adler Power Wound Signature .010–.048 sets

Dunlop Tortex 1 mm picks

What gear did you record with?

Adler: I’ve always used the Mesa/Boogie Mark IV, which has the built-in 5-band EQ, but these days I have been real keen on the [Mesa/Boogie] Triple Crown, and I’m running the Boogie 5-band EQ pedal through the effects loop on that. I love it.

Morton: I’m using the Mark IV. And then, guitar-wise, I use Jackson Dominions—my signature model. I use a couple of different versions of that. And I used a Gibson Les Paul that Josh has with an EverTune bridge on it, which is great for the studio. I’ve used that on the last four or five albums that Josh and I have worked on.

How do gear choices differ for live performances?

Morton: Live, I use a Mark IV and a Mark V. In the studio, I’m like, “Just slap something in the chain and see if it sounds cool!” [Laughs.] But live, I like everything to stay the same—I’m real specific about my signal path, and I like my Sennheiser wirelesses because they have this kind of built-in compression that becomes part of the tone. So, there are little weird idiosyncrasies, but my rig is relatively straightforward. I’m not one of these guys that has a pedalboard that looks like a dining room table. It’s just a few pedals.

Is there any gear that you secretly geek-out on that nobody would be overtly aware of?

Morton: I get real geek on tubes, but I can’t get the ones I want anymore. Boogies used to have Russian Svetlana 6L6s shaped like a little weird bulbous light bulb. I have a little box of them in my studio that I only use for special occasions, because you just can’t get them anymore. You can really hear the damn difference, too, man. It’s a slight, subtle kind of compression or sucked up gain structure—just a little bit smoother, silkier, and tighter. I can get close with other stuff, but there’s just something special about those tubes. So, I geek out about that. I’m super OCD about my rig—I don’t like changing.

Adler: Probably my amp. I just want to make sure that I have the amp that I’m used to, and I know what the controls are. I’m just such a creature of habit. You put another amp in front of me, I’m like, “I don’t get it—it’s too many knobs!” [Laughs.] I get overwhelmed, and it’s like, “Just give me the amp that I’m used to,” which sounds silly. I’m sure that I could mess around with another amp and have it sound great, but I just get so used to stuff.

Who were some of your influences when you were first coming up on guitar?

Adler: Kirk Hammett and James Hetfield were, definitely, very early on. There is an acoustic guitar player named Leo Kottke who is real percussive and who I always thought was really cool. I always wanted to be able to do that, even though I can’t, but he definitely inspired me to pick up the instrument. And Nick Drake, with his moody melodies. In a songwriting kind of facet, that’s what my ear gravitates towards—real minor-key kind of stuff.

Morton: My earlier influences were mostly classic-rock guys. And Eddie Van Halen was my personal guitar hero. But my top three are Jimmy Page, Jimi Hendrix, and Billy Gibbons.

Have you seen the ZZ Top documentary on Netflix?

Morton: I haven’t seen that yet, but everyone’s raving about it. I’m planning to watch it this week. I heard it’s really, really good.

There are scenes of them rehearsing in Texas, and it’s just amazing to hear the tones coming out of those instruments and the effortlessness with which they’re able to conjure that stuff up.

Morton: It’s just touch, man. Stevie Ray Vaughan is the same way. They just have this touch. You can’t teach it. It’s a human thing. That’s the beauty about this playing guitar shit that we do: You can tell me how to play something, you can set the amp up the same way you play it and hand me your guitar, but it’s going to sound different. There’s just a human element about this that can’t be contained, and it can’t really be translated. And Gibbons … his note choices—like, the places he stops—are so unique. Guys like him and Clapton, when they stop, they’ll stop at a place that I wouldn’t necessarily have thought of to land. And that’s the kind of shit where I’m like, damn. Any of us can play that note, but when that’s the last stone you stepped on and then you stopped for a minute, that’s what made it gain all that personality. That’s the shit I pay attention to when I listen to those guys.

Do you practice guitar techniques when you have downtime, or do you focus on crafting songs?

Adler: I would say it’s about 70 percent writing and crafting songs, and then, once an album is done, it goes full force into making sure that those songs are as tight as possible by rehearsing the set. As far as techniques, it goes back to being self-taught: I hate to say I don’t know any techniques, but I just kind of do what I do. I would daresay 60 percent of my time is spent with a guitar in my hand, doing something. Whether I’m documenting riffs or practicing, I’m always playing. I’m sure I practice some techniques along the way [laughs].

Feast on this full set from Lamb of God’s current lineup, including drummer Art Cruz, from last year’s Resurrection Fest in Viveiro, Spain.

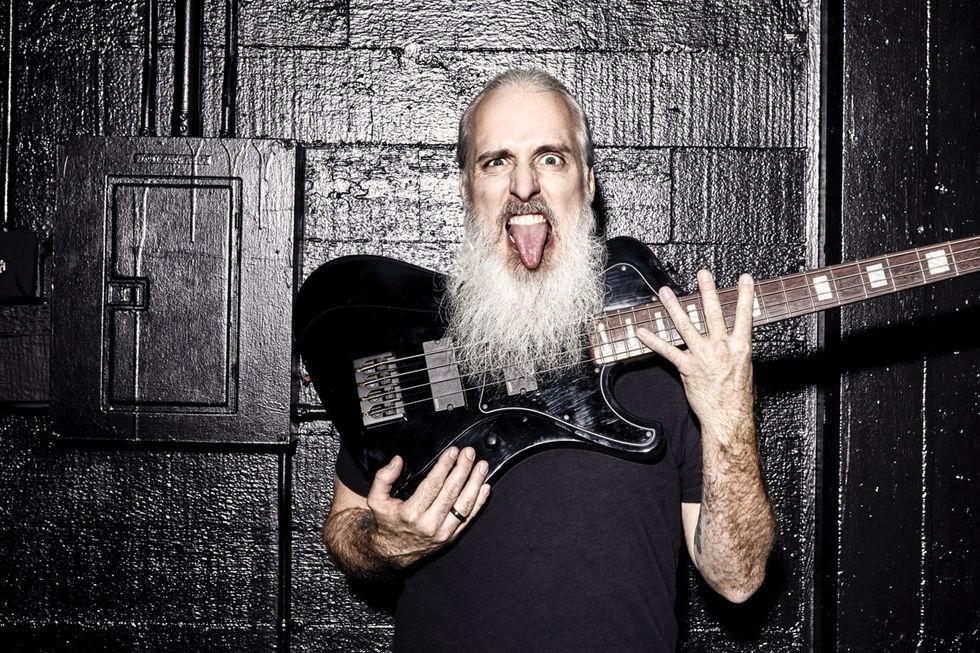

The bassist’s style is as original as it is heavy. “I never really looked up to people outside of the ones that were in my face,” he says of his early woodshedding days. Photo by Bill Hall

John Campbell—Lamb of God’s Bottom-Liner

Bassist John Campbell’s role in Lamb of God might appear unassuming, but his indelible contributions, formidable and fluid, cast a rhythmic and sonic foundation for the band’s titanic guitar riffs and provocative lyrics.His style is grounded in an unorthodox approach to learning and plying the craft. As a kid, Campbell eschewed bass players most would consider essential listening, choosing instead to feed off the musicians from the vibrant local music scene in Richmond. Additionally, for many of his formative years he played a 3-string bass, sans G-string, as a snub to the 5- and 6-string basses that were becoming popular at the time. Such ingenuity and attitude has made him unique—simultaneously guttural yet cerebral, and bombastic yet succinct. And now, with his otherworldly Gandalf-like looks, Campbell’s onstage presence only seems to magnify his breaks with convention.

We spoke with Campbell from his home, also in Richmond, and he was happy to discuss influences, his right-hand technique, his relationship with new drummer Art Cruz, and producer Josh Wilbur’s work with the band.

How do your contributions shape what Mark and Willie write?

When they bring songs in, it’s open to everyone making suggestions on arrangements and riffs. But over the years, those guys have gotten better and better at what they are doing, and they fine-tune it quite a bit before it gets to us. A lot of times, they will play the bass on their demos, and they’ll play it right along with the guitar, in the same spot on the neck. I’ll bring that down and kick it around to something with way more low end. And there will be times when they’re playing super-complicated riffs that really just need a whole note held down underneath—at least for part of the riff. And those are the sorts of things that I put in there. I don’t know that I would go so far as to say that those make it a signature Lamb of God song—I think that power comes primarily from Mark and Willie—but I’ve been holding up my end alongside these guys. I think we’ve come to create a pretty nice team.

Choosing when not to double a complicated riff, but instead complement it by being more bass-centric, must take some restraint.

I might be guilty of not doing that as often as I should, because I love the riff. I love playing sick riffs. That’s why I’ve fallen into doing what I do. But you’re right, it’s holding back that’s needed to give the songs depth and make them more dynamic than just dudes pounding the same exact note along with each other the whole time.

Guitars

ESP JC-4FM John Campbell Signature basses

Amps

Mesa/Boogie Bass 400+

Mesa/Boogie Standard PowerHouse 8x10 cabs

Effects

Darkglass Microtubes B7K Analog Bass Preamp

EBS MultiComp True Dual Band Compressor

Tech 21 SansAmp Bass Driver DI

Strings and Picks

DR DDT-45 .045–.105 sets

InTune GrippX 1.14 mm picks

This is your first album with Art Cruz on drums. How seamless was that transition for you, as his battery mate?

I think that there are some subtle differences between the guys, although Art learned to play drums by looking up to Lamb of God and Chris Adler. So he comes heavily steeped in the style. That said, there was some feeling each other out. In the beginning, we’d turn and look at each other for specific cues. Whereas, having played with Chris for years, we all knew exactly where the hits were. So there was some fine-tuning on points like that. As far as subtle differences, Art is just this insane ball of energy and he’s going to hit everything on the razor-sharp perfectly. So he kicked a little fire in my ass, and it feels dangerous. It feels more exciting.

Who are some of your early influences?

Here in Richmond, Virginia, there’s this band called GWAR, and their bass player, who went on to form Kepone, is a guy named Mike Bishop. He’s an insane bass player: just power and talent and all fingers and singing at the same time. I remember seeing him in my early days of playing bass and was like, “Holy shit, that guy is phenomenal. I need to be able to play like that guy.” And now he’s returned to GWAR. I think he picks up the bass every now and again, but he’s the frontman now.

Did you ever try to emulate another player when you were younger, or delve deeply into someone else’s playing style?

I never really looked up to people outside of the ones that were in my face. I would never sit down with a record and be like, “Oh my god, that guy’s bass line just blew my mind. That’s incredible. I want to do that”—except for maybe when I heard Metallica. I would never, in any way, shape, or form, say that I’ve spent my career trying to emulate Cliff Burton, but holy shit, that dude was amazing. And I guess it’s kind of cliché to say at this point, but I’ve certainly taken the time to learn a couple of Metallica riffs that are just insanely fun to play.

Have any newer or up-and-coming bass players caught your ear?

There is one guy I follow on Instagram who is an amazing, sick bass player—Nick Shinz [aka Nick Schendzielos], who played in Cephalic Carnage and Havok. He’s just an insanely talented dude.

Why is playing with a pick critical to your role in Lamb of God?

What I do professionally, there’s no way in hell I can pull that off with fingers. Using a pick is so much more precise and exacting. But if I’m trying to be purist at the time that I’m playing those Metallica riffs, I’ll drop the fingers. I actually started the Burn the Priest stuff with all fingers. It’s definitely nice to get back to a pick after you’ve been on your fingers for a while. That shit hurts, man! [Laughs.]

Josh Wilbur seems to be Lamb of God’s George Martin. Can you encapsulate what he brings to the band?

Well, he’s insanely talented. He’s an incredibly good human being. And he told me one time that a big part of producing is psychology, and so I guess his manner of psychology works incredibly well with Lamb of God. With Josh, I think we’ve done our best work.

I would say he’s more the guy who convinces you that you can do anything. When a taskmaster is needed, he’s cracking the whip—he’s got a schedule to keep. We have deadlines, and he’s the guy who that responsibility falls on. So when we’re complaining, “Dude, come on…. We want to take tomorrow off.” He’s like, “No, we’ve got to get through two more songs before we can take another day off.”

- Lamb of God Delivers Scorching Take on a Bad Brains Classic - Premier Guitar | The best guitar & bass reviews, videos, and interviews on the web. ›

- Harakiri for the Sky Defies the Rules of Heavy - Premier Guitar ›

- Rig Rundown: Amenra - Premier Guitar ›

- What Does the Horn Hand Mean? - Premier Guitar ›