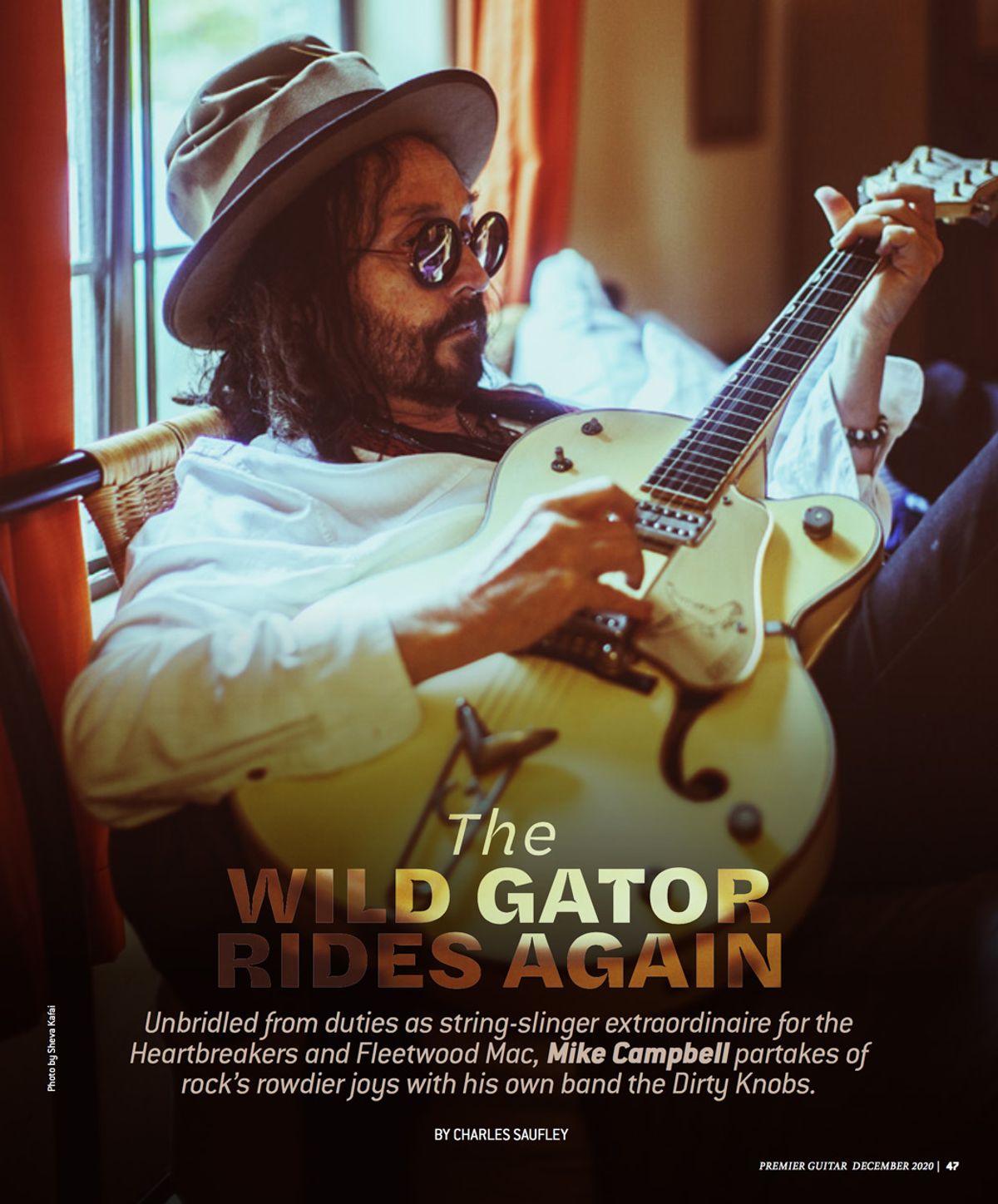

Unbridled from duties as string-slinger extraordinaire for the Heartbreakers and Fleetwood Mac, the wild gator partakes of rock’s rowdier joys with his own band the Dirty Knobs.

Though he is one of the planet’s humblest guitar heroes, Mike Campbell is fearless about walking in the shoes of legends. Playing alongside Bob Dylan, he punctuated the poetry of folk rock’s greatest scribe—dishing his take on Mike Bloomfield and Robbie Robertson’s bee-sting leads. As a member of Fleetwood Mac he stood in for Peter Green and Lindsey Buckingham. And on many nights with Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers he would take George Harrison’s yearning slide solo from the Traveling Wilburys’ “Handle with Care.”

But over the course of a career spanning nearly 50 years, Campbell steadily made the case for his own status as legend—not just as a trusty, tasteful sideman supreme to superstars, but as co-writer of rock ’n’ pop masterpieces. “Refugee,” “The Boys of Summer,” “Stop Draggin’ My Heart Around,” “You Got Lucky”: Each features Campbell’s name as co-author—and guitar hooks of such startling grace and elemental potency that they burrow in the memory like the afterimage of a perfect sunset.

More than a decade ago, Campbell took the helm of his own band, the Dirty Knobs—an irreverent, spontaneous unit that veered from originals to a grab bag of ’60s and ’70s deep-cut covers and curiosities. But with the Heartbreakers and Fleetwood Mac taking the lion’s share of Campbell’s time, there was rarely time to accomplish much other than the occasional run of California club dates.

At last though, the Dirty Knobs have an LP to call their own. With producer George Drakoulias (Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers, Black Crowes, Primal Scream) offering sonic and song-curation counsel, Wreckless Abandon was whittled down from a backlog of eclectic originals to a slab of boisterous, rockin’ economy that reflects the rowdiest and most irreverent side of the band. But as casual conversation, or a tour of his must-see Instagram feed reveals, Campbell is a wellspring of creativity, gentlemanly warmth, and musical knowledge, with a deep reverence for the magic of music creation and the many masters that came before him.

I saw four of the Heartbreakers’ San Francisco Fillmore shows in 1997. They were so loose and free. And when I first saw the Dirty Knobs about 10 years ago, the eclectic, irreverent mood was very reminiscent of that Fillmore experience. There were touches of Revolver-era Beatles, some surf stuff. Did that Fillmore run inspire your approach with the Knobs, or was it just an itch to play outside the formality of the bigger Heartbreakers shows?

Well, I’m honored that you heard the energy of those Fillmore shows in the Dirty Knobs, because that was one of the absolute highlights of my life. I loved the Heartbreakers. So I never put a record out or pursued the Dirty Knobs as long as the Heartbreakers were together. But now that those windows are open, it’s what I want to do. The other thing is that the Heartbreakers were required to play a lot of familiar songs every night. We couldn’t change up the set list too much. The Fillmore wasn’t like that, we could do whatever we wanted. And with the Dirty Knobs I can do whatever I want, too. I can go into a Beatles song we’ve never rehearsed before in the middle of a show. There’s a freedom and spontaneity I really enjoy.

When I’ve seen the Dirty Knobs, the song selection was pretty eclectic. But this record has a very strong Southern-rock and Texas-boogie thread. What drove the band or your songwriting in that specific direction this time around?

Well, we never wanted to be any certain type of band. And back in Florida when the Heartbreakers started out, we didn’t want to be part of the Southern-boogie thing. We were way more into the Yardbirds and Beatles and Kinks than the Allman Brothers, so we always resisted that connection, even though we grew up in the same area. I’ve never really chased that type of thing—it’s never really been part of my soul. With the Dirty Knobs we record all kinds of songs. But when we were putting the record together I was having a hard time because there was so much different material. So George Drakoulias came in and honed it down to songs in sorta one groove. And as it turns out, there’s a bit of boogie and Southern rock in there. It was not a conscious effort, but there is a lot of that element in there alongside the British stuff.

Wreckless Abandon was recorded in Michael Campbell’s home studio and produced by George Drakoulias. The band cut the tracks live, all in the same room.

I heard a touch of Sir Douglas Quintet in “Pistol Packin’ Mama.” That Vox organ has a way of tilting a song in a specific direction really fast doesn’t it?

I love the Sir Douglas Quintet! And you know we actually got (Sir Douglas Quintet organist) Augie Meyers to play that part.

I had no idea!

That’s keen of you to pick up. I love Sir Douglas and I love Augie, so we had the track and one day I just said, “Wouldn’t it be nice if we could get Augie to play on this?” And George said, “Let me call him up.”

Your voice even sounds a bit like Doug Sahm on that one.

[Laughs.] It was certainly influenced by him. It’s a very tongue-in-cheek song.

“I Still Love You” tends toward a darker, more melancholy, melodic structure. There’s a touch of minor-key Zep heaviness to it. But you’ve written and co-written some fantastic melancholy-to-somber stuff. Things like “A Woman In Love,” “You Got Lucky,” and “Boys of Summer” all have very melancholy underpinnings. Are those moods harder to explore when you inhabit that character as a frontman? A melancholy song can be quite a weight to bear as a songwriter and lyricist.

Songwriting is a very mysterious process. And the minor-key, melancholy thing for me comes from listening to a lot of blues, or songs like “While My Guitar Gently Weeps.” The minor-key stuff touches a really mournful, deep, bluesy part of your soul, and sometimes I naturally gravitate toward that. Other days I’ll want to do something that’s really up. But it’s not a conscious effort—it’s really about what gift of inspiration you’re given that day. Sometimes working in a minor key can feel really serious—like okay, we’re really getting down to the shit here. But even in classical music—most of my favorite pieces are in minor keys. It’s interesting.

Do you have a songwriting ritual you adhere to?

Well, that’s all I’m doing right now. I do have a ritual, but I still really don’t understand how it all happens sometimes. It’s so mysterious and beautiful when something comes to you out of thin air. And you definitely can’t force it. I have a studio at home and typically the dogs wake me up at 6 in the morning, I’ll have some coffee, hang out with my wife, and when things settle down, I head over to the studio. A lot of times though, I’ll just listen to music—often to stuff I grew up with—and that will inspire me. I’ll hear a chord or rhythm, try to figure out what it is, and that gives me a departure point. Lately, I write a lot in the mornings because I don’t want to be a total hermit.

Michael Campbell has a legendary guitar collection, and he keeps it interesting onstage. Here he’s playing a late-’60s Dan Armstrong lucite model. Photo by Lindsey Best

Do you need specific headspace? Or do you just typically react to the emotions and events of a given day?

I just try to be open, because it’s like switches going on and off in your head—you’re sitting there noodling on the guitar and stuff just starts channeling through you. It’s the strangest feeling—without being too heavy, it’s a little like being close to God or something. “Here’s a gift for you son! What can you do with it?” Then it turns off and it’s gone ’til the next time [laughs]. But I’ve never been able to just sit down and write a song on demand—they can happen when I’m driving or watching a movie—just out of the air at the most random times.

What songs that you’ve have written really gave you the feeling that you’d struck gold or really hit something special? Where you really knew you were on a roll?

In the moment, I always think that the song I’m working on is the greatest thing in the world. Then I’ll look at it later and realize it’s not so great. But I had the benefit of having an amazing songwriting partner [Tom Petty]. When I worked with him, I focused on the music and he took care of the lyrics. But I could visualize where he would sing from knowing him so well. It was always a thrill. I might give him a CD with 10 musical ideas on there and he might pick two, or none, or one. But when he would come back and say “I’ve got something that goes with that song” and all of the sudden it was “Refugee” or “A Woman In Love” or “Stop Draggin’ My Heart Around”—my mind would be just blown thinking, “My God, how lucky am I?”—having my little idea become a classic song.

It seemed like you used to pull Tom in a certain songwriting direction at times.

Yeah, I don’t like to pat myself on the back. But yeah, I guess if he hadn’t heard the music, then that song wouldn’t exist. That’s just the way a songwriting partnership goes.

“I had the benefit of having an amazing songwriting partner,” says Mike Campbell about Tom Petty. “When I worked with him, I focused on the music and he took care of the lyrics. But I could visualize where he would sing from knowing him so well. It was always a thrill.” Photo by Ken Settle

Do you primarily write around the guitar these days? In the ’80s you worked a bit more with the Linn machine and keyboard textures.

Mostly I write on the guitar. Occasionally I’ll sit down at the piano. “A Woman In Love,” “You Got Lucky,” and “Boys of Summer” were all keyboard-written songs. I love piano, and I can get around well enough to write songs. But the guitar is just so deep. There is so much in there, and I’m amazed at how often I find a new chord passage or phrasing that was sitting right there in front of me the whole time.

Do you tinker with alternate tunings at all?

Oh yeah, sometimes I’ll pick up a guitar I haven’t seen in two years, and it will have landed in some weird tuning and I’ll write on that and try to figure out what the heck I’ve just done. But mostly I use various slide tunings like the Keith Richards tuning [open G].

Do you still enjoy studio nitty gritty? The process of tinkering? Or was that ever an enjoyable part of it for you?

I love the studio. I learned organically over the years by being in the control room a lot and learning how to operate studio gear and get sounds. With Pro Tools I’m still a bit limited and learning. I have it set up so that I’m basically using it as a tape machine. But yeah, I do love to tinker. I probably had more patience for digging into crazy production shit when I was younger. These days I want to get the song down before I forget it.

ForWreckless Abandon, were most of the band together in a room?

Yeah. I made a conscious decision to make it all live, with no click tracks. I wanted everybody to play at the same time and I think you can really hear the interplay on the record. We did it in my home studio. I asked George Drakoulias if he thought we should go into a proper studio and he said, “You’re just going to run up a big bill and it’s not going to sound any better than what you have going on.” So that was encouraging.

Do you still use a fairly analog-oriented signal chain and favorites that you return to?

My sound is pretty basic. It goes through an old Neve console on the front end and I just make sure I have nice mics and preamps in the mix and that goes straight into Pro Tools, which, again, I look at as my tape recorder now. The quality of tape isn’t what it was. And with Pro Tools the tape doesn’t run out every 15 minutes or in the middle of a jam. I love the convenience of Pro Tools for pure tracking, but still love keeping everything else as analog as you can get.

Do you have favorites among your analog outboard stuff?

Yeah, I have that Neve 24-track console and another sidecar Neve 12-channel that’s actually the machine that the Wilburys used, and those have beautiful EQs and preamps in them. [Editor’s note: Both Neve desks have vintage 1073 modules.] Next to them I have a Soundcraft 1600, which Dave Stewart turned me on to—that’s the Full Moon Fever board. I send guitar into that a lot. I have a few Neumanns—U 47s and U 87s and few AKGs. For guitar though, I like using a Shure dynamic mic on the amp and a nice condenser out in the room. If you’ve got a good instrument and a good mic, usually you’ll be okay.

Do you miss some of those old studios you used to work in?

I prefer my own joint because you don’t have to dick around with unfamiliar stuff. Things will be right how you left them the day before. But I have really fond memories of Sound City, Cherokee, and Sunset Sound.

I’ve always worked a lot in my home studio, too. It’s comfortable to me. If I’m not on tour, I like to stay home. I’m not a partier and I don’t go out much. I mostly work in my studio, so things aren’t much different than they were in the old days, in a way.

You’ve worked with so many producers of renown, all of whom have very different styles. From whom did you learn most?

Well, all of the Heartbreakers’ producers have been very different. And I think it’s really good to bring in someone new every two to three records to shake things up. I learned a lot from all of them. But the producer I learned the most from is Jeff Lynne. I think part of it is that he’s such a great musician, and working with him was different than anyone else. He’s so bright, and so fast. He always knew exactly what to do and how to do it quickly, and he’s just so full of ideas!

His system is not about recording a live band—that’s the one thing I don’t totally endorse. But it was really the only way to get the songs to work the way we wanted for Full Moon Fever. He works on one part at a time, but that’s how he gets that pristine sound where nothing bleeds into anything—it’s all on its own track and sounds good by itself and fits into the whole.

Guitars

1959 Gibson Les Paul

1956 Fender Telecaster with B-bender

1950 Fender Broadcaster

Late-’60s Vox Starstream

Amps

1954 Fender Deluxe

1963 black-panel Fender Princeton

Early-’60s blonde Fender Bassman

’60s Ampeg Rocket

Duesenberg Berlin

Effects

Dunlop Cry Baby Wah

Dunlop Way Huge Camel Toe Triple Overdrive

Line 6 DL4

Line 6 MM4

But he’s just so brilliant on so many levels. He knows when a lyric should be better, or when a chord isn’t that good, or if a song needs a better bridge. And he was so quick with coming up with parts.

My approach to guitar parts has always been off the cuff. In the Heartbreakers I would have ’em cue up the cut and I would play along with no preconceived ideas. But Jeff would come in after a session break and already have thought of whole parts. He’d ask if I had any, and I’d say, “Well, not really.” And he’d say, “Well, I’ve got one.” And it would always be great! But that really drove me to stay up and think of something good, so the next time he’d ask, I’d say, “Oh yeah, I have an idea.”

But it was always so fun. It always felt like we were moving along and we never got bored with it. There were just so many ideas sparking off from start to finish. And man, we’d start a song at noon and by 5 or 6 o’clock it would be done—ready to mix. I’d never seen that before.

That’s interesting, because typically if you want to get something done fast, you put a band in a room, wind ’em up, and let ’em go.

Well, Jeff always seemed to know what he wanted, and knew how to get it. Tom and I were more used to making it up as we go. I’d learn so much from his weird methods. We’d want to do a snare drum and it wouldn’t be sounding right, and he’d walk in and point the overheads at the ceiling. And I’d be thinking, “What the fuck is he doing that for?” And I’d go back in the room, and be like, “Oh man, that just pulled the whole thing together.” I learned a lot from Rick Rubin and Jimmy Iovine. But they weren’t musicians; they tended to see things from a non-musician’s or listener’s point of view—which is really valuable, too.

I feel like many of the more rockin’ tunes have some of that ’59 Les Paul tone that you explored in the Heartbreakers’ later years. Is there a lot of that guitar on the record?

I used that as my main guitar unless I needed a 12-string or something that was really screaming for a Fender sound. Jason Sinay, the other guitar player in the Knobs, usually played a Stratocaster, and between the Gibson and the Strat, we’d usually get a pretty good blend.

For the benefit of our readers that may never have the chance, what exactly do you feel when you play a 1959 Les Paul?

With that particular guitar you feel a lot of things. When I’m not recording, I don’t play it that much. It’s the only one of my guitars that lives in its case, really. But when I do pull it out—first it just feels really comfortable. But you can’t help but feel all the great parts that have been done on that same type of instrument. And, it’s weird—when you pick up that guitar and play a Jimmy Page lick, it sounds just like that! And you think, “Oh man, that’s how he got that sound going! … It’s this thing!”

It’s also so easy to play. But it’s not just an overdriven loud guitar by any means. It has beautiful clean tones. Plus, it has those neck pickup tones that really—only a Les Paul does that. I also feel really honored to have it. So when I pick it up to play something, I feel like I have to do something really, really good to deserve it.

Do you manipulate the controls much to get tone variations?

I’ll pretty much use the tone controls all the way up—or totally down with the neck pickup for that Clapton thing—and if I go to the middle pickup position I may ease up on the bass pickup volume a little bit because it can get too muddy. Generally, I’ll leave everything up. But the great thing about that guitar is that you can turn down the volume and the high-end tone doesn’t go away, so you can get some nice rhythm sounds just by playing on 8 or so, which takes the distortion out and leaves you a nice, even, clean sound.

Your guitar collection is peppered with some very unusual and unorthodox instruments—things like the Vox Starstream. Do you ever build songs around the more eclectic parts of your collection?

Oh yeah, I do that all the time. We did a song called “Lockdown,” and that’s all the big Vox hollowbody [’67 or ’68 Vox Grand Prix] with the same built-in fuzz and wah as the Starstream. That whole song is that guitar. But yeah, sometimes I’ll be working on something and I just don’t want that same old thing that I do. So I’ll look around and there’s a tenor guitar, or a dulcimer, or a tamboura. And yeah, sometimes you build a whole song around that instrument.

Campbell onstage with a Gibson Custom Shop replica of his prized '59 Les Paul, his main guitar for the new Dirty Knobs album, Wreckless Abandon. Photo by Andy Tennille

How about the B-bender? You have a very lyrical style—and again, a very melancholy feel—with that instrument. Your style is also quite outside the dogmatic Nashville/Bakersfield approach. It reminds me of the way Jerry Garcia bent the traditional role of the pedal steel.

I love the B-bender, and obviously I loved Clarence White, but I really loved the way Jimmy Page used a B-bender to play blues instead of country. And you can get a really languid, dreamy sound out of it if you bend to those blue notes rather than resolving where you would with a country chord. It’s a very sad, expressive sound, and I really like to use it that way. Thank you for noticing that.

That Telecaster, by the way—the one I use for most of my B-bender stuff—man, I’m such an idiot. Many years ago I was in the [San Fernando] Valley and I stopped at some music store I’d never seen before. And they had that ’56 Telecaster for sale, without a B-bender on it. I might’ve paid 600 bucks for it. I wanted to put a bender in one of my Telecasters and for some reason I picked that one. Man, I would never do that to a ’56 Telecaster now! It worked out good though, because a lot of that sound you hear is just a really amazing instrument at the root of it. It’s a very special Tele.

You’ve spent a long time now in your Princeton-and-Deluxe phase. It seems like you’ve really settled on that recipe. What about that works for you?

I loved playing through AC30s and my Bassmans and Kustoms. But as the years went on, Tom was really struggling to hear himself over the loud amps. When I first started playing with the Dirty Knobs in the clubs I was using my Bassman, but it was so loud. Just as an experiment, I went down to a [black-panel] Princeton and started mixing that with the tweed Fender sound and they sounded so good! They balance each other out so well. So I brought that back to the stage with Heartbreakers. But you put that tone through a big PA, man—I mean that’s basically what Neil Young uses—a little Deluxe sounding like 18 Marshalls. I also had a Duesenberg amp (Editor’s note: Most likely a 45-watt, 2x6L6 Berlin model), and for some overdubs we’d use that because it was a little bit louder. I also used my old Ampeg Rocket, which we used on Full Moon Fever a lot.

Have you fallen for any new guitars or tone combinations of late?

You know, I’ve been playing a Fender Mustang with the (competition) stripe that was a gift from Tom a lot lately. That thing sounds great! But I’m always falling in love with something new. I sorta have a sick obsession with guitars, if you couldn’t tell.

In this clip from 1985’s Pack Up the Plantation: Live!, Mike Campbell cuts loose in a flurry of Jeff Beck/Jimmy Page-style fire on “It Ain’t Nothin’ To Me.” Sadly, for Campbell fans, the band rarely performed the song after this tour.

- Beyond Blues: Mike Bloomfield’s Manic Magic - Premier Guitar ›

- Mike Campbell Likes the “Real Stuff” - Premier Guitar ›

- Two Recent Books Offer Music History You Can Hold - Premier Guitar ›

- Robbie Robertson, Lead Guitarist of the Band Has Died - Premier Guitar ›

- Robbie Robertson—Canadian Father of Americana - Premier Guitar ›