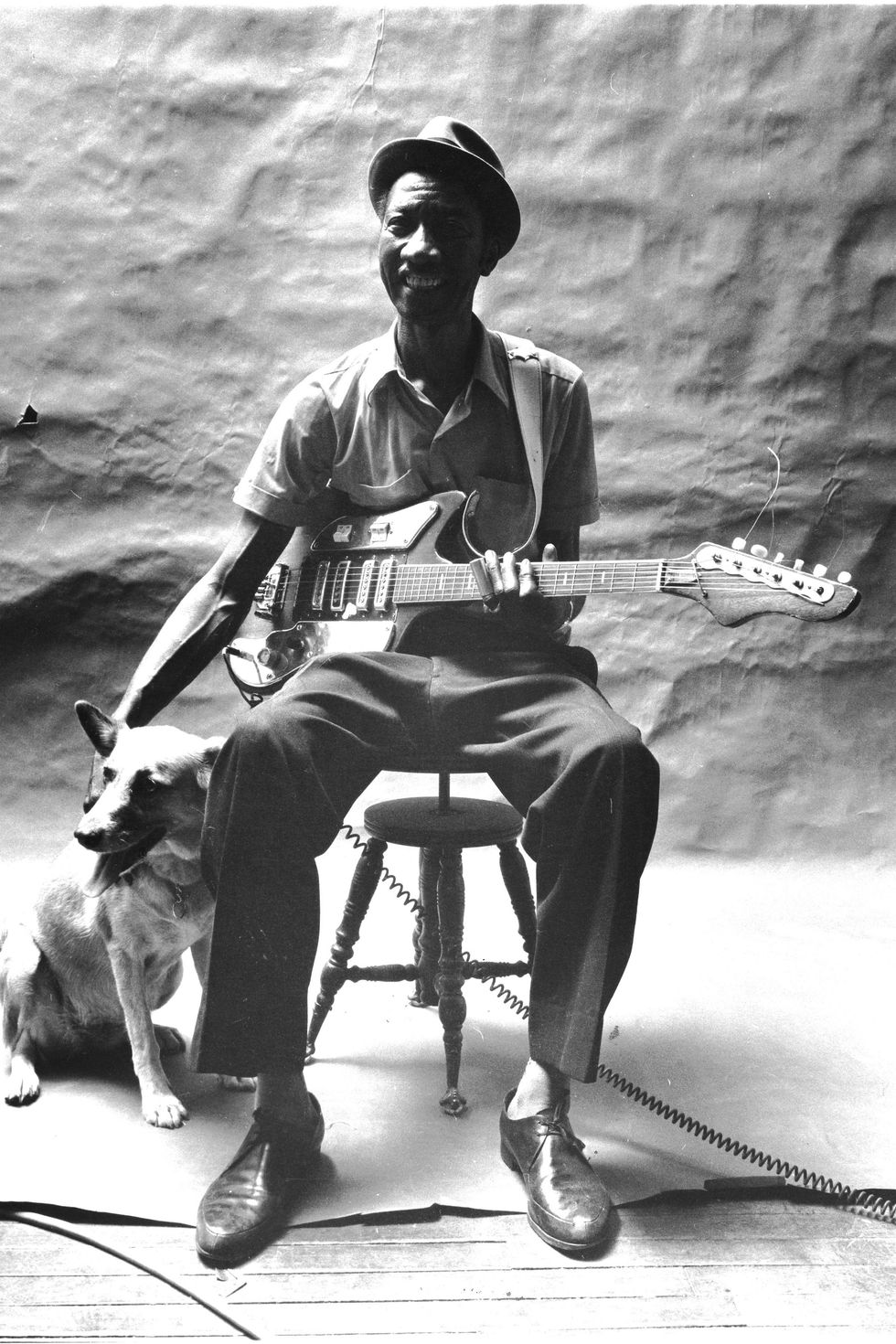

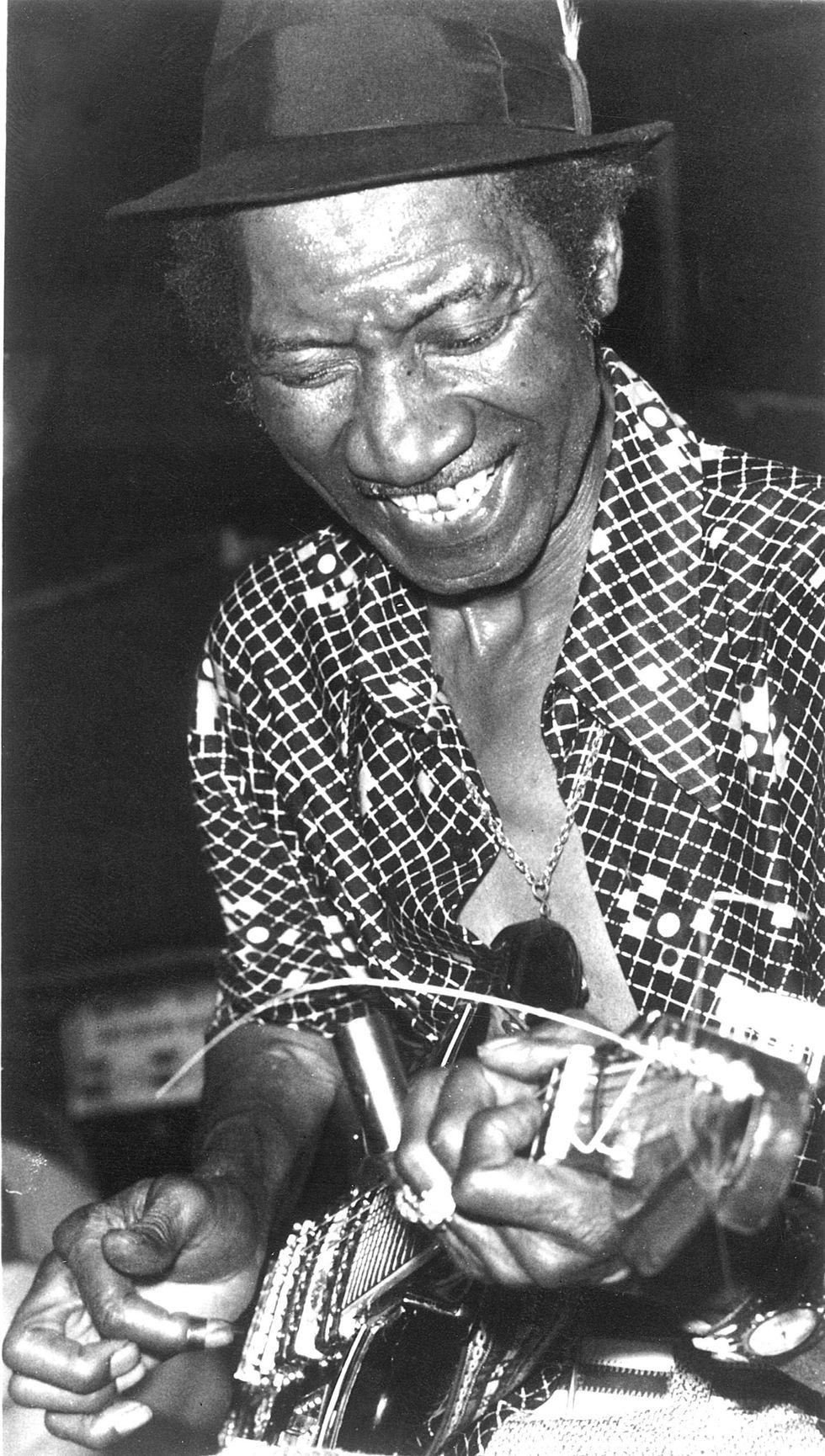

Hound Dog Taylor looks typically jovial while cradling his Kawai-made Kingston S4T. Note the length of his slide, on the fifth of six fingers on his left hand. It is longer than the width of his guitar's estimable neck.

Cheap guitars, cheap booze, and amps on stun—the shaggy tale of the legendary court jester of Chicago slide-guitar blues.

What magicians really practice is subterfuge. The noisy blues mage Hound Dog Taylor was a master. His quote, "When I die, they'll say 'He couldn't play shit, but he sure made it sound good,'" is emblazoned on a T-shirt, over a photo of his 6-fingered fretting and sliding hand. And his stage persona—laughing and joking at warp speed and bullhorn volume, drunk, Pall Mall dangling from his lips, a huge slide raking his Kawai Kingston's strings in a way that made his amp detonate fragmentation bombs—was that of a barroom jester. But there is genuine magic at the nucleus of Hound Dog's wild-ass playing, for the effect it had on audiences and the story in sound it still tells.

"Anybody who heard Hound Dog live and says they didn't have a good time is lying," attests John Sinclair, the American counterculture hero who helped present Taylor while serving on the board of the Ann Arbor Blues and Jazz Festival in the early '70s. "He'd start his sets by yelling, 'Let's have some fun!' And everyone did. He's my all-time favorite artist."

The perpetually struggling musician from Natchez, Mississippi, could barely read words, but Hound Dog read his audiences like Shakespeare, using songs like "Wild About You Baby" and "Give Me Back My Wig," and his trio the HouseRockers' almighty groove, as helium for lifting hearts. He also knew how to find the soft spots in aching souls, with his tear-wringer "Sadie" or the nakedly abject "She's Gone."

"Anybody who heard Hound Dog live and says they didn't have a good time is lying."— John Sinclair

As a Black man raised in the depths of the Jim Crow Delta, then living and performing mostly in the hardscrabble urbanity of Chicago's South Side, Taylor knew the score and used his music to settle it. Although Hound Dog's been gone for 46 years, defiant joy still rings in the sound of the three singles and two studio albums he cut in his lifetime. And especially in live recordings, where he and his team, because they were more than a band, of co-guitarist Brewer Phillips and drummer Ted Harvey ran wild—as loud, carefree, and outrageous as they cared to be, not giving a damn about anything. Their brash, braying, and self-possessed music is the sound of freedom and, in the context of African-American history, even rebellion. And those who can't hear that through the raggedy tones and occasional hiccups are making the mistake of merely listening with their ears.

Young Dog’s Blues

Theodore Roosevelt Taylor was born in either 1915 or 1917 in Natchez, about 85 miles north of Baton Rouge, on the banks of the Mississippi. The small city's boomtown days were past. Its status as the lower river's nexus of steamboat traffic was erased by the expansion of railroads. But it continued to be a lively music town. In 1940, Natchez was the site of the infamous Rhythm Club fire, where 209 people lost their lives after being trapped inside the wood and steel building where Walter Barnes, a well-regarded contemporary of Duke Ellington, was leading his Royal Creolians orchestra.

By then, Taylor—whose first instrument was piano—was playing guitar and singing all over the Delta, when he wasn't driving a tractor on the farm where he worked. He had even appeared on Sonny Boy Williamson's popular King Biscuit Time live radio show on station KFFA in Helena, Arkansas. Two years later, Taylor hastily relocated to Chicago after the Ku Klux Klan burned a cross in front of his home in retaliation for an affair he'd had with a white woman. For the first day, he crawled through drainage ditches and hid in fields as he made his way north.

In this out-take from the photo session for his debut album, Taylor has his Kingston with a metallic pick- and body guard—and an amiable canine companion.

Taylor was born with polydactylism, a condition that causes the formation of additional fingers or toes. Both his hands had six fingers. Although the sixth wasn't functional, his fifth was extra-large, and some theorize that its additional bulk and strength may have helped him more aggressively pin the strings with his slide. At one point, as fable has it, he tired of being razzed for his difference and used either an axe or a straight razor to cut off the extra finger on his right hand. The resulting pain and blood led him to leave the left alone.

For his first 15 years in Chicago, Taylor played gigs but made a living via day jobs. Under the spell of Elmore James, whose early '50s singles established him as a star, the Dog began playing more and more slide, crafting his own raw distillation of James' keening, cutting, aggressive style and even copping his bawling vocal approach. In 1957, Taylor was building cabinets for televisions when he made the decision to chase the muse full time. Two years later, he met guitarist Brewer Phillips on a gig, and the HouseRockers began to gestate.

Through the '60s, Taylor eked out a living in Chicago's Black working-class bars, which stayed open long and late. At some point, he got the nickname Hound Dog, which, let's face it, is cooler than Teddy Roosevelt. Tales vary, but it was either bestowed upon him because of his tireless pursuit of members of the opposite sex, or because he actually did look like a canine, with his prominent ears, large nose, and rounded eyes. He reportedly developed a pre-show ritual of downing a shot of whiskey, a mixed drink, and a beer in quick sequence just before taking the stage, which he'd then command for a series of sets sometimes stretching to six hours or more. The typical fee was $30 for the band, bumped up to $45 on weekends.

Hound Dog Taylor, natty as always, digs in hard for some single notes. See the steel pick on his right index finger? That's part of why his sound is often so explosively bright.

Photo by Jack Lardomita

In 1965, he and Phillips added drummer Ted Harvey, and their sound coalesced. With Harvey as their tireless sparkplug, they developed a loose but brilliant language by meshing their guitars. Mostly Hound Dog took the lead, with his slide and howling voice, while Phillips laid down a stone-finger-buster riff as a bassline. Often when you hear an instrumental by the HouseRockers, like "Phillips Screwdriver," that's Brewer at the fore, aggressively playing patterns or fiendishly mean 'n' dirty single-notes in a style gleaned from his early lessons with the great 6-string innovator Memphis Minnie. In truth, Phillips was a better player than Taylor, but Hound Dog had the schiznit, and—with his crew at his side—laid it down like Godzilla.

Enter the Gator

Three singles between 1960 and '67, including a release on the Chess subsidiary Checker, did nothing to enhance their fortunes. In '67, Taylor somehow obtained a slot on the American Folk Blues Festival tour of Europe, but he hated the experience, because his style didn't mesh with his fellow travelers, which included Little Walter, Koko Taylor, Son House, and Sonny Terry & Brownie McGhee. But in 1970, the coin flipped. Music-loving, recent college grad Bruce Iglauer had moved to Chicago for a job at Bob Koester's famed Jazz Record Mart and Delmark Records operation, and to chase the city's thriving blues. Taylor had told him about a regular Sunday gig he held down at Florence's Lounge, at 5443 Shields Avenue, on Chicago's South Side. It was a classic workingman's bar in a standalone building made of brick and cinder blocks, with a cubed-glass window and a dark, wood-paneled interior. As anyone who has pursued regional music styles to their depths knows, this is the kind of lair where wizards can sometimes be found. And on one afternoon in 1970, that's where Iglauer found Taylor, Phillips, and Harvey.

Iglauer recounts that afternoon, right down to the beads of sweat trickling down Taylor's cigarette-smoke-clouded face, in 2018's Bitten by the Blues: The Alligator Records Story, which he co-authored with Patrick A. Roberts. Talking about that gig 51 years later, revelation still rings in his voice. "It was the most fun I'd ever seen anyone have playing music," he attests. "I remember grinning all afternoon. They were so happy that it was like watching kids pretend to make music with brooms instead of guitars. Ted Harvey worked at a loading dock for Montgomery Ward, and Brewer Phillips worked construction. Hound Dog was the only one who made a halfway living playing music. So their only motivation for being there was to have fun."

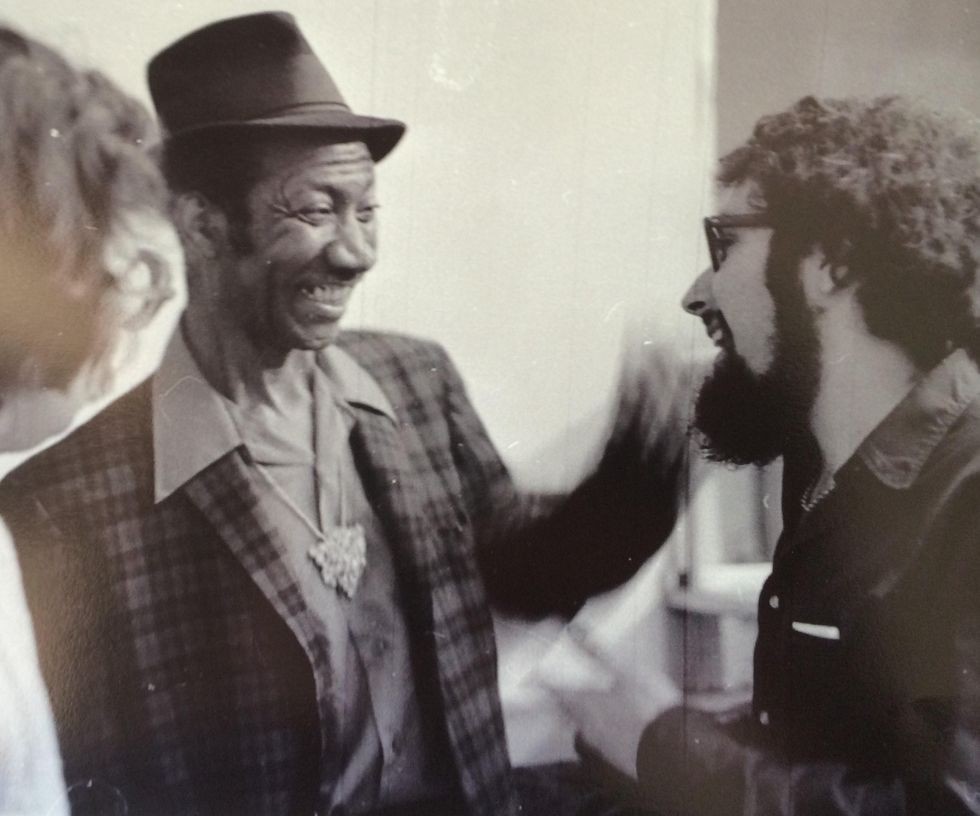

The meeting of Hound Dog Taylor and Bruce Iglauer was a turning point for both men. Taylor rose from Chicago's working-class bars to club, festival, and college stages around the world, and Iglauer became the proprietor of what would become the leading independent blues label, Alligator Records.

Photo by Nicole Fanelli

Beside colorful stories about his travels with the group—how Ted Harvey rarely drove because he'd end up motoring against traffic on the wrong side of a superhighway, Taylor sitting up all night in his hotel room with the lights on because he was frightened of having a repeated dream about being chased by wolves, Taylor's epic slide-guitar battle with J.B. Hutto, the trio's relief finding a Kentucky Fried Chicken in Australia after resigning themselves to starvation—the period also gave Iglauer an intimate view of what and how they played.

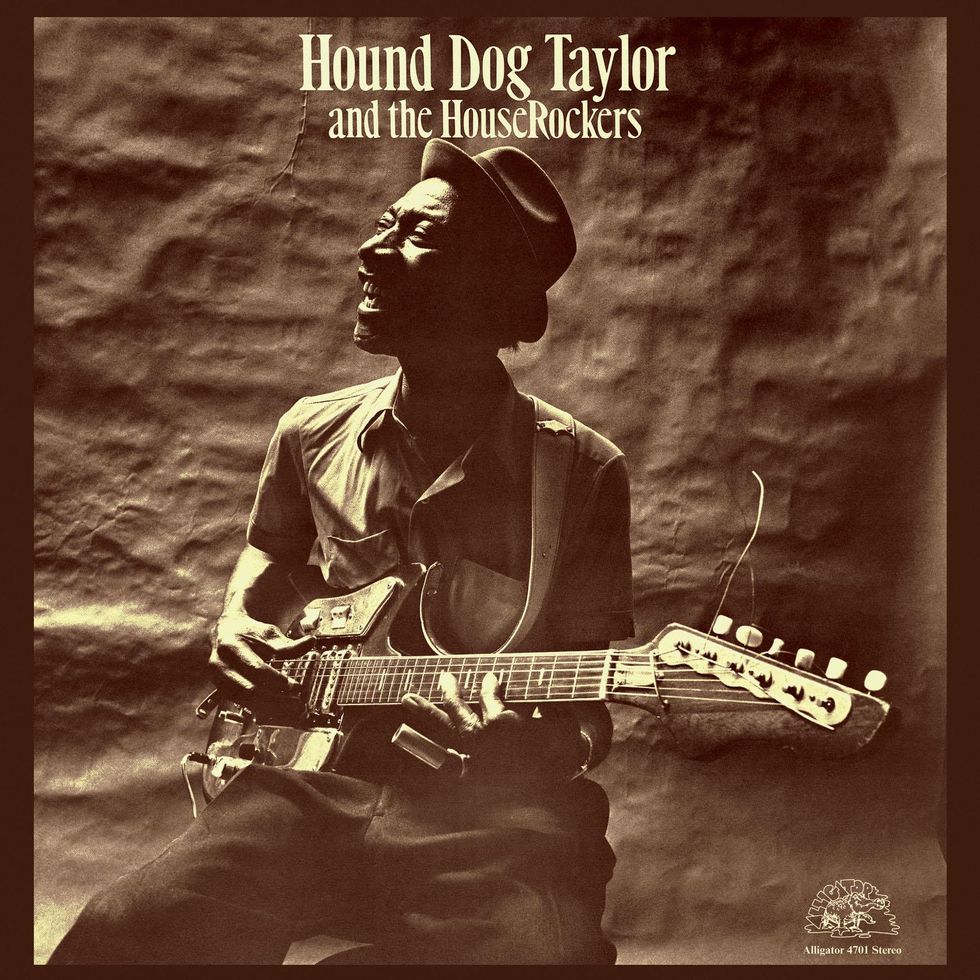

That day was transformative for both Iglauer and Taylor. After failing to get his boss to sign Taylor to Delmark, Iglauer used a $2,500 inheritance to pay for two days of studio time, then started Alligator Records to put out the results, Hound Dog Taylor and the HouseRockers, in 1971. Natural Boogie followed in 1973. Today, Alligator is the world's largest independent blues label, celebrating its 50th anniversary and a storied history that includes hundreds of titles by Albert Collins, Johnny Winter, Son Seals, Lonnie Brooks, Lonnie Mack, Koko Taylor, Buddy Guy, Junior Wells, and other legends. But for the next four years, Iglauer shepherded Taylor, Phillips, and Harvey in the studio and across the world's stages. He describes the trio's chemistry as "equal parts brotherly love, vicious adolescent rivalry, and Canadian Club."

How They Rocked

Taylor's main amp, the one heard on Hound Dog Taylor and the HouseRockers, was a Silvertone 1400-series piggyback 6-speaker combo—a 60-watter he turned about as high as possible. That's the key to Taylor's gleeful distortion: funky gear and sheer volume. But Iglauer notes that he also witnessed Hound Dog play through a Peavey 1x15 and a Fender Super, and even, during a soundcheck at the Ann Arbor festival, into a Fender Twin with a Gibson Les Paul. "Hound Dog always sounded exactly the same."

The HouseRockers' chemistry was "equal parts brotherly love, vicious adolescent rivalry, and Canadian Club."—Bruce Iglauer

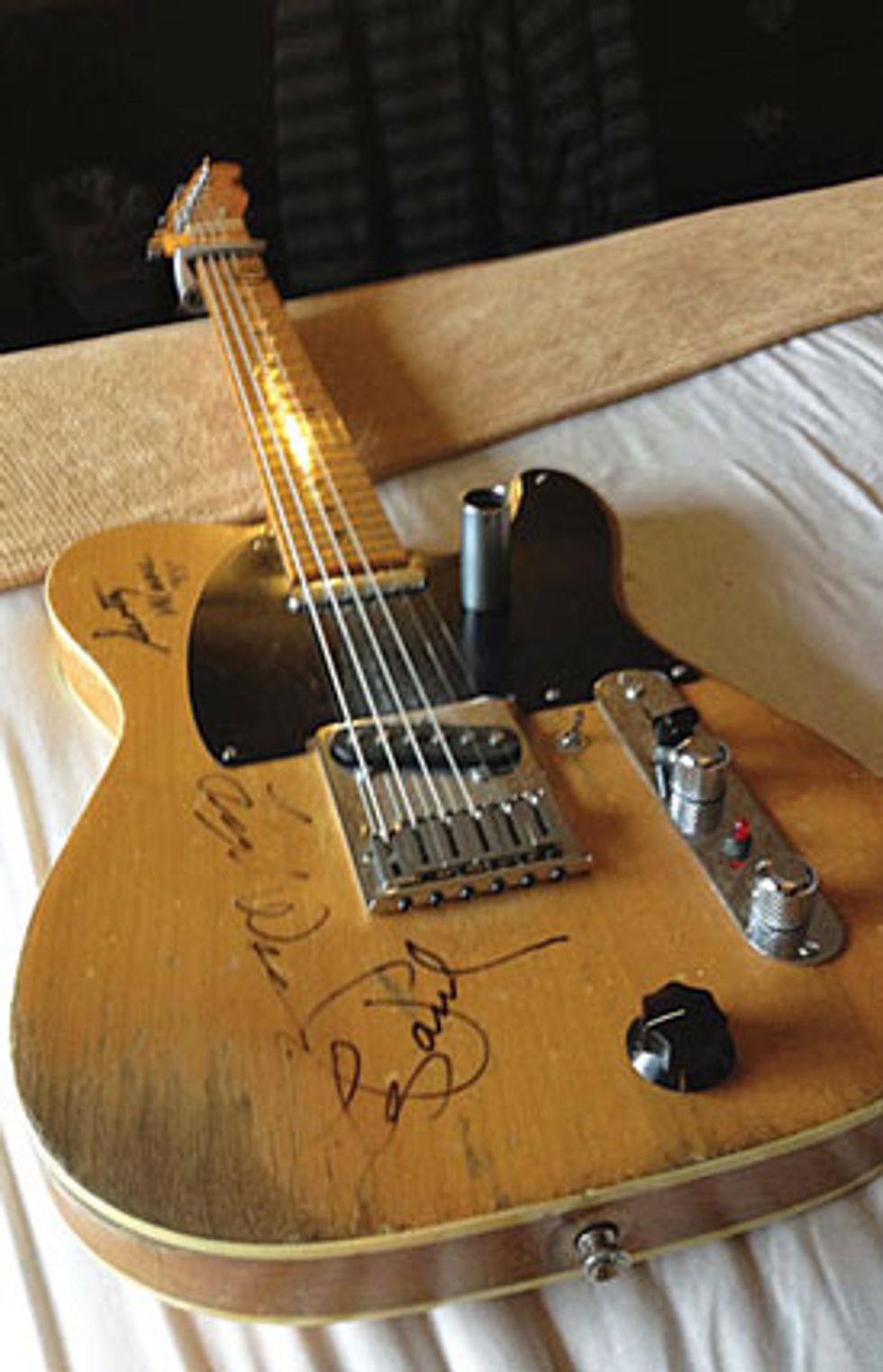

Taylor's guitars of choice were a pair of Kawai-made Kingston S4Ts, with fat necks, whammys he didn't tend to use, an on/off slider for each of four pickups, and master volume and tone controls. One had a Telecaster pickup subbed in, plus a metal pickguard and upper body protector, and both of these then-$50 pawnshop specials were difficult to keep in tune, but perfectly suited to Hound Dog's raw exhortations. Dan Auerbach owns one of these guitars and played it on the Black Keys' most recent album, Delta Kream. (For more on this guitar, see "Dan Auerbach Summons the Ghosts of Mississippi Blues" in the May 2021 issue.)

"Hound Dog did not dampen the strings like some slide players do, and essentially approached the instrument like Elmore James, but in an even more aggressive fashion," says Iglauer. Taylor also made his own slides. He'd slice metal tubing from a kitchen chair, long enough to extend across his guitar's neck, and then pound a piece of brass tubing into it, so it would fit his finger better and have more weight.

Listening to Taylor's first two albums, plus the posthumous live release Beware of the Dog! and the live-and-studio-leftovers Release the Hound, provides a strong vision of the trio's dynamic. Harvey is a surprisingly adept drummer and takes breaks where his rhythms veer in jazz-inflection directions. Taylor is heavy handed, tempering his ringing, grinding, often-turbo-speed slide with barking single notes to open up his verses, and chords that smash with sledgehammer audacity. The steel pick he wore on his right index digit adds to the shrillness of his tone—especially when he pecks out single notes like a brawny rooster. And Phillips plays far more than basslines on his guitar, even when fulfilling that role. His figures are packed with nimble variations, although he never shortchanges the pulse, and his solos offer a scalding challenge to copycats.

Taylor's debut album was produced and released by Bruce Iglauer, and established his Alligator Records imprint. The label is celebrating its 50th anniversary this year.

"Hound Dog's tuning was typically somewhere between open E and open D," Iglauer continues. "They tuned by ear, so it was relative." Especially after the night wore on and the whiskey bottle emptied. "Once, Hound Dog tried to quit drinking, but it was terrible. His hands couldn't stop shaking, and he couldn't play, so he started again."

The Other Side of the Dog

Like the animal whose name he wore, Hound Dog Taylor loved being with people. Fans around the world knew him as funny, warm, smiling—the perpetual genial host. "Even when he was at home, he was 'on,' just like he was onstage—the life of the party," says Iglauer. And whenever the young record man visited Taylor's apartment, it was buzzing with visiting friends and relatives. But in his quiet times, Taylor often appeared sad and regretful. "He seemed to feel that he missed out on a lot of things in life," says Iglauer. And he persecuted himself over what he saw as a lack of musical and practical education. "I don't believe he appreciated the depth of his own soulfulness or the transcendent joy that his music created."

Oddly, one of Taylor and Phillips' joys was argument. Once, they bickered all the way from Boston back home to Chicago, a 983-mile trip, about whether Hub City radio station WRKO was AM or FM. "One morning, after an all-night drive, Hound Dog woke up in the back seat of the car and noticed Ted Harvey was asleep in the front," recalls Iglauer. "He smacked Ted on the back of the head and yelled, 'Wake up and argue.' This was not always good or funny. In his book, Iglauer recounts finding Taylor and Phillips in a violent argument behind a club, knives drawn and out for blood. "I don't know what would've happened, because their tone made me feel like they really wanted to kill each other." Acting fast, he reminded both men they had a show contract to fulfill, and the battle stopped. "I think they were looking for an excuse to put their knives away," he says.

Hound Dog Taylor - 15 minute LIVE Ann Arbor 1973 Video

Here's Hound Dog Taylor onstage at the Ann Arbor Blues and Jazz Festival in 1973, with the HouseRockers, being his ebullient self. Listen for the pointed tone of his fingerpick on the single-note turnaround and the braying spray of tones that emerge from his ferocious slide. At times, it's really not that far from Sonic Youth, although it's always stone blues.

In May 1975, they went too far. During a visit to Taylor's home, Phillips made a tasteless joke about having sex with his wife, so Taylor shot Phillips in the arm and thigh with a .22 rifle. That ended the HouseRockers, and a few months later Taylor was in the hospital with inoperable cancer in his lungs and neck—his last stop before the great gig in the sky. Iglauer was a frequent visitor, and on his final stop-by, two days before the Dog slipped away, he was leaving as Phillips arrived to make amends with his friend. Taylor died on December 17, 1975.

"I don't believe he appreciated the depth of his own soulfulness or the transcendent joy that his music created."—Bruce Iglauer

Because of his half-century helming Alligator Records, Iglauer has known nearly every major electric blues artist, to varying degrees. When asked where Taylor fits in the pantheon, he pauses a moment, and then mentions George Thorogood, the band GA-20 … just a tablespoon full of direct torchbearers compared to the likes of Alberts King or Collins, or B.B and Buddy, or, of course, Stevie Ray Vaughan. "What Hound Dog did in terms of technique is not difficult," he says. "You can put your guitar in open tuning and find his notes. Hound Dog played simplified Elmore James, with slide chords and sliding and single notes on individual strings, but that groove …. his rhythm. Hound Dog was all about that groove."

That raw sound, that groove, and the pure joy of being alive that resonates in the music of Hound Dog Taylor makes me think of a quote from another great record man, Sam Phillips. The Sun label chief famously described the music of another musical canine, Howlin' Wolf, as coming from "a place where the soul of man never dies." Hound Dog Taylor's music also comes from that place.

Inside of a Dog—Approaching the Style of Hound Dog Taylor and Brewer Phillips

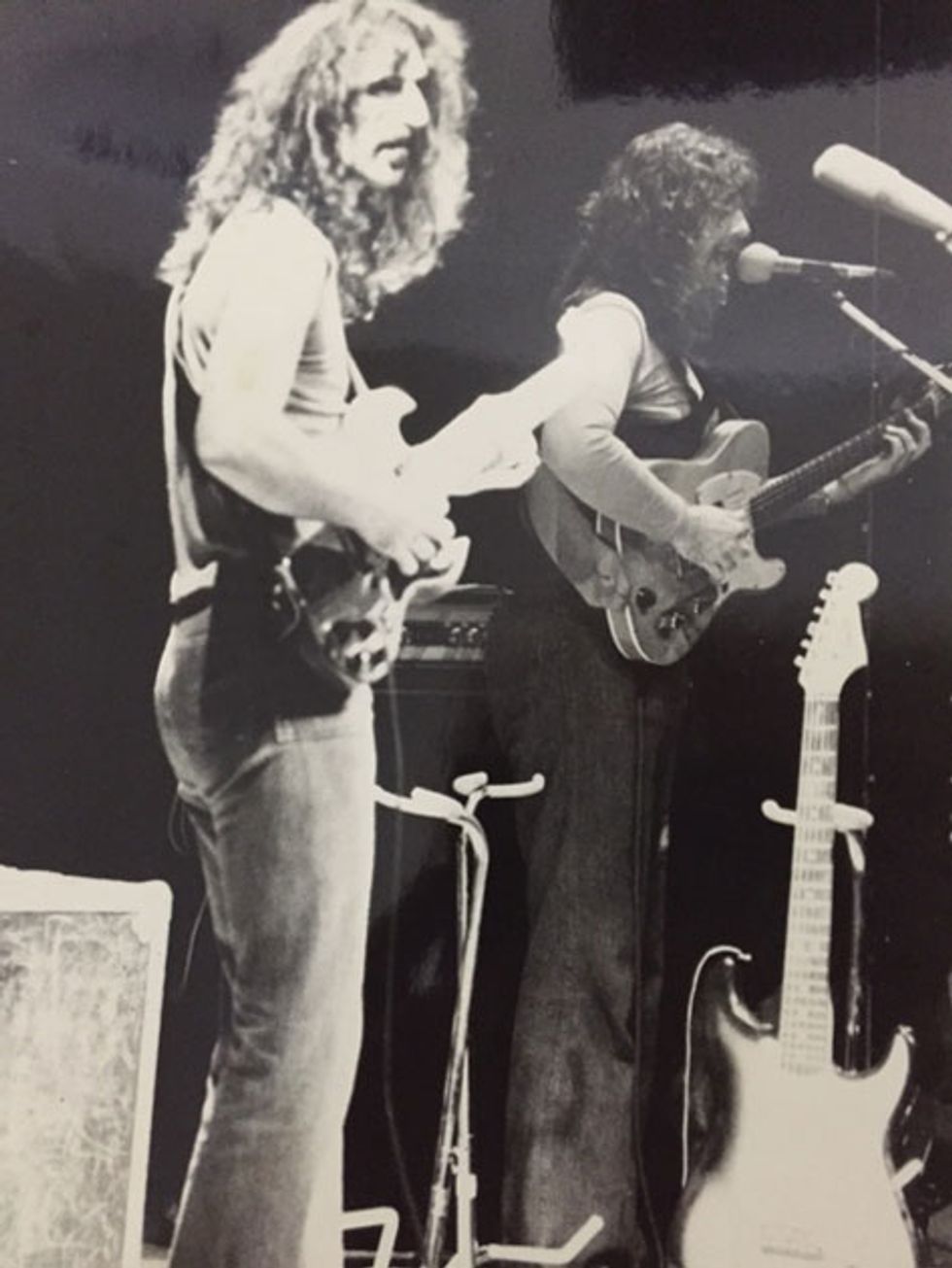

Pat Flaherty, left, and Matthew Stubbs took on the roles of Hound Dog Taylor and Brewer Phillips for their band GA-20's new album.

Dissecting the music of Hound Dog Taylor and the HouseRockers is like conducting an alien autopsy. Things might sound and look kinda familiar, until you get deep inside, where offbeat stops and turnarounds, staggering shuffles, fast-flowing arteries of single notes, and fat-ass grooves abound.

GA-20 guitarists Matt Stubbs and Pat Faherty took their scalpels to the task to prepare for their new album, GA-20 Does Hound Dog Taylor: Try It … You Might Like It! "We've always loved Hound Dog's stuff, and real Chicago blues," explains Stubbs, whose main gig is with blues legend Charlie Musselwhite. And GA-20's two-guitars-and-drums lineup also makes the HouseRockers a natural frame of reference.

For their tribute album's 10 songs, Faherty played the role of Taylor and Stubbs chased Phillips' approach. Faherty found a Kawai-made relative of Hound Dog's Kingston, a Teisco, on eBay just before the sessions. "The sound is really in those pickups," he observes. "As far as intonation goes, you can't get the cheaper versions to go in tune past the second fret, and their strings couldn't even be lined up over the pickups correctly. So you have to get a better model, like Hound Dog had. I need a little tension when I pick, because the guitar is tuned to open C#, so I used .012s. Hound Dog would use that tuning, and his version of Elmore James's 'It Hurts Me Too' is almost in F." Faherty figures Taylor tuned mostly in the neighborhood of open D or Eb, and adds that E tuning is audible on the live recordings.

Faherty's initial experience playing slide was as a student at Berklee, under the guidance of jazz and textural guitar guru David Tronzo. "Hound Dog's style is super-loose, and the thing about his tone that makes him different from a lot of other slide players is that when he goes for it, he digs really hard. You can tell by the shrill attack that he's not smooth. The sound is very biting and in-your-face."

Stubbs offers that "Brewer was the secret weapon in the band. He solo'd like a madman. I've listened to Hound Dog my whole life, but had never gone through Brewer's style with a microscope before. Some of the turnarounds he used to play, like in 'Give Me Back My Wig'.… I remember thinking, 'Man, if I'm going to get close to this, I'm really going to have to double down.' He filled all the gaps with some really sophisticated playing. Brewer wasn't just following Hound Dog. He was constantly creating these little melodies on the side. And there are places where they dropped bars and changed rhythms, and you'd think they messed up, but then you listen to the live recordings and find out they made these changes together every time."

Stubbs favored a '51 Telecaster for the sessions at his home studio, and a reissue when he needed to tune down to C#. For amps, Faherty mostly used a Silvertone 1471, 5-watt, 1x8 combo. As for Stubbs' own main amp, it was their band's namesake: a 16-watt Gibson GA-20 combo.

A look at the life and legacy of the guitarist Miles Davis recruited in the mid ’70s when he wanted virtuosic playing on par with Hendrix and Muddy Waters.

In the early to mid 1970s, Miles Davis changed musical directions. That wasn’t unusual. Davis did this often—he was at the forefront of almost every innovation in jazz. But the direction of the 1973–75 incarnation of his band was unusual. Although Davis had already gone electric in 1969 with the release of In a Silent Way, as radical as some of his early electric work was, it was nothing compared to the bombastically epic avant-funk he’d unleash just a few years later. And at the epicenter of that mid-’70s lineup—the nuclear bomb Davis dropped on jazz—was the late, great guitarist Pete Cosey.

Cosey was an imposing figure: A large man with big hair and a long beard wearing flowing robes and dark glasses. He performed seated and was surrounded by guitars, handheld percussion instruments, and a floor full of stompboxes. And his playing was unlike anything else. It was a sonic adventure—innovative, complex, dissonant, abrasive, yet ambient, subtle, and rooted in the blues. It was always tasteful and appropriate, regardless of how far out he took it.

But Cosey was no newcomer when he joined Davis. His impressive resume included stints with a who’s who of the late-’60s Chicago scene—serious gigs with big names in R&B, early funk, blues, psychedelia, straight-ahead jazz, and the city’s burgeoning avant-garde movement. An insatiable tinkerer, Cosey experimented with tunings, pedals, synths, and butchered instruments in his never-ending quest for an elusive tone.

Mainstream success eluded Cosey, but his reputation and influence are massive. His former collaborators adored him. His protégés revered him. Most consider it criminal that he never reached a larger audience. He was a singular and uncompromising talent—his music was an extension of who he was—and in the process, he redefined the way the guitar is played.

The Explorer

Peter Palus Cosey was born in Chicago on October 9, 1943. His mother worked as a pianist and songwriter. His father played the saxophone and worked with people like swing-jazz pioneer Louis Jordan, bluesman Big Bill Broonzy, acclaimed jazz saxophonist Sidney Bechet, and French-American entertainer Josephine Baker.

an elusive tone.

Cosey moved with his mother to Phoenix, Arizona, following his father’s death when he was around 9 years old, but returned to Chicago as a young adult and remained there for most of his life.

Cosey played a number of different instruments. He had some formal training on piano, but he was a self-taught guitarist. He credited some of his later innovations on guitar—like alternate tunings and controlled feedback—to his earlier education, experimentation, and big ears. It also didn’t hurt that his parents created an environment that was open to world music and fostered exploration. For example, he told All About Jazz in May 2008, “I have an appreciation of [Indian] music through my father. He field-recorded in India, between 1936 and 1938. The first curry I ever tasted was prepared by my father, when I was a child.”

The future Davis sideman’s first major gig was as a session guitarist for Chess Records. “I must have done a thousand blues sessions,” he told writer George Cole in an interview for the book The Last Miles: The Music of Miles Davis, 1980-1991. He played on the incredible Fontella Bass hit “Rescue Me,” and did sessions with Etta James, Jackie Ross, Major Lance, and many others. He even worked with Chuck Berry. “[Berry] had just gotten out of prison,” Cosey told Cole. “We cut some great things with him—they were really rocking. I remember we did 31 takes of one song, only because he was rusty. They had me play his signature lick for him and it was an honor.”

But Cosey’s most notable work for Chess was on the label’s late-’60s psychedelic experiments featuring Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf. The albums Electric Mud, The Howlin’ Wolf Album, and to a lesser extent, Waters’ follow up After the Rain, were a conscious effort by Chess to market the blues masters to a younger audience. The albums were a commercial success—Electric Mud was Waters’ biggest-selling album at Chess—although certain blues purists weren’t convinced. “I remember Pete telling me about how much Howlin’ Wolf hated his playing,” says Cosey collaborator and bassist Melvin Gibbs (Rollins Band, Defunkt, Decoding Society). “Muddy was maybe half convinced when they recorded Electric Mud, but once that first album sold so well he was, like, ‘Yeah, I love this boy.’ But Howlin’ Wolf was never convinced. Pete told me that Wolf told him—Pete had a big afro at that time—‘Yeah boy, you need to go get a haircut, and while you’re on your way to the barber shop, take that bow-wow pedal of yours and throw it in the lake.’”

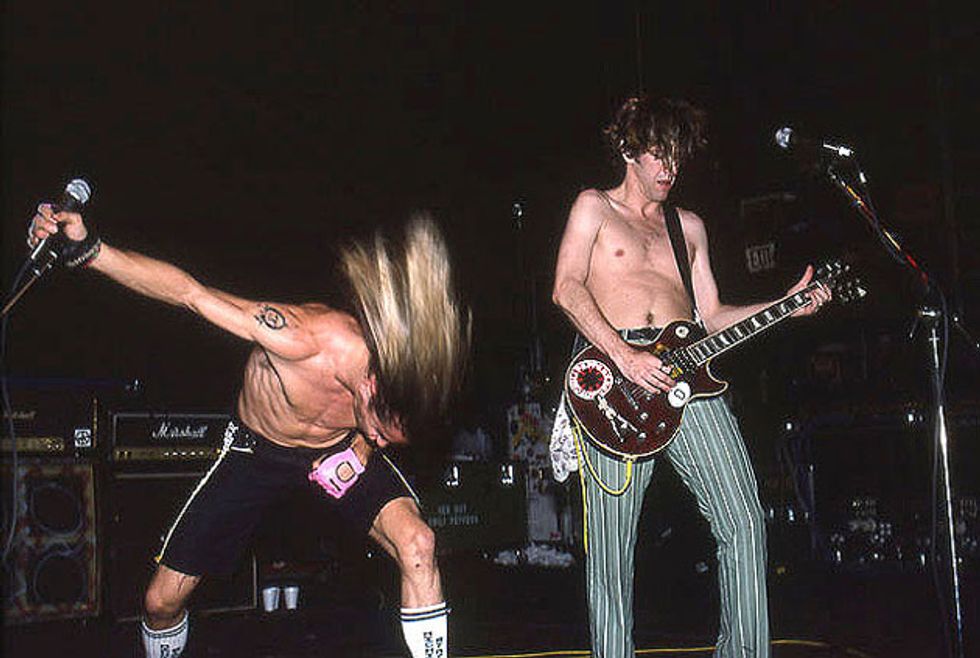

Cosey, in his customary seated position (center left in green pants and shades), onstage with Miles Davis in Japan.

Photo courtesy of Sony Music

Despite Howlin’ Wolf’s misgivings, Cosey’s playing on those records shines like that of an original, mature musician and hints at what was to come. Some of his best performances are on Electric Mud’s “I Just Want to Make Love to You” and “Herbert Harper’s Free Press News.” Cosey’s sound is the real deal—someone steeped in the traditions of the Chicago scene, pushing the sonic envelope, stretching out harmonically, yet stamping it all with his unique thinking and personality. Cosey wasn’t a student of a tradition. He was a living extension of that tradition, constantly building on it.

“Those are some of the greatest albums ever,” Gibbs says. “I’ve heard that Led Zeppelin used to listen to those albums before they went onstage. That’s the level of influence they had.” Although difficult to corroborate, legends abound. In addition to Zeppelin, Jimi Hendrix and the Rolling Stones are said to have drawn inspiration from those albums. Years later, hip-hop icon Chuck D of Public Enemy championed Electric Mud by reassembling the original band for the “Godfathers and Sons” episode of the 2003 Martin Scorsese-produced documentary series, The Blues.

Already somewhat of a gearhead, Cosey had a small arsenal of go-to instruments at that time. “Pete used his trusty Gretsch Tennessean, along with a ’58 Fender Stratocaster and a customized Gibson ES-125 modified by Phoenix luthier Bill Ross to include 24 frets and a single cutaway,” Bill Milkowski wrote in Guitar Player in July 1990, describing the instruments Cosey favored as a session man.

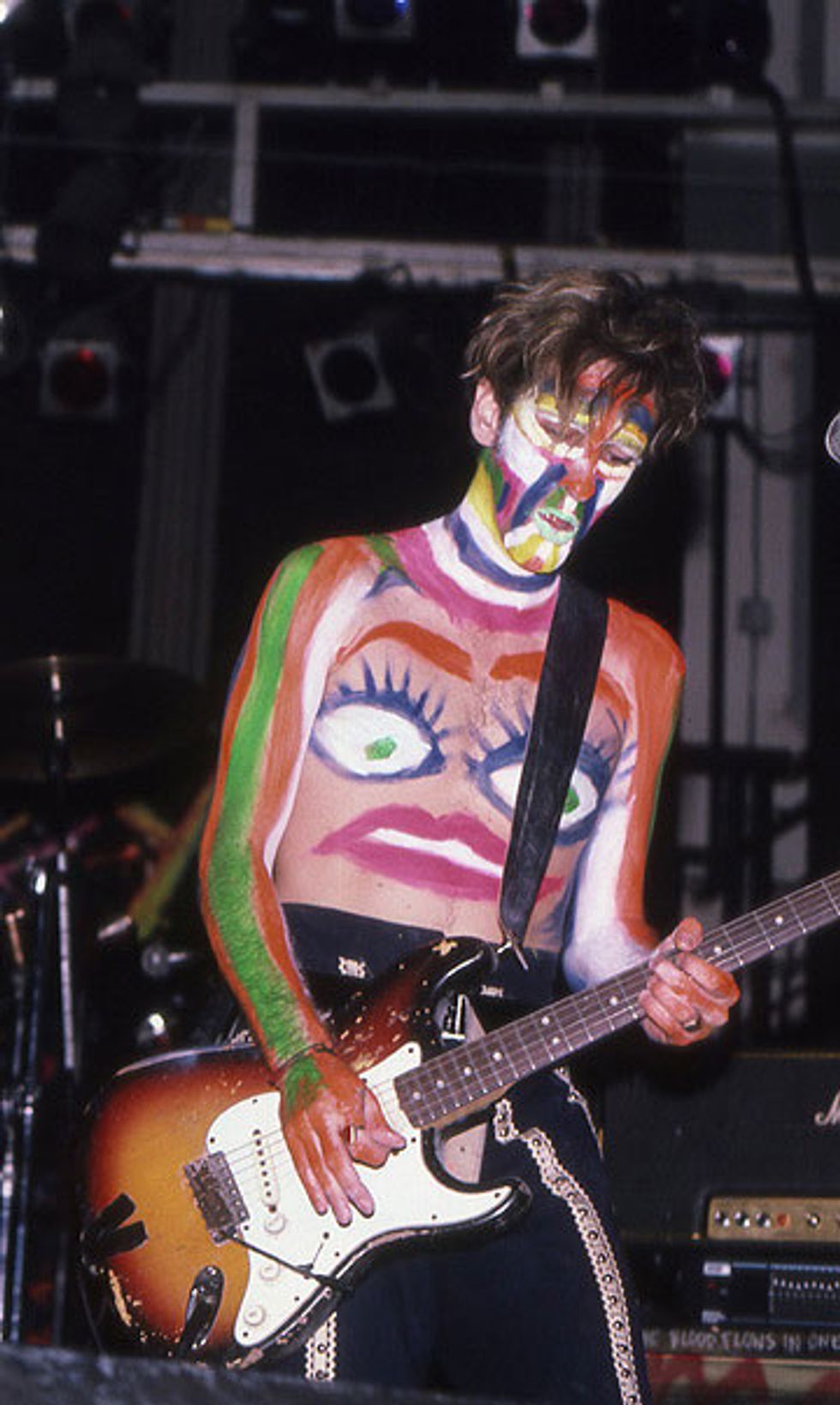

In this 2009 photo, Pete Cosey strums the very same Morris Mando Mania guitar he often played onstage with

Miles Davis in the ’70s. Photo by Audrey Cho

Cosey’s work wasn’t limited to Chess in those days either. He toured with Aretha Franklin, Jerry Butler, and did sessions for Motown as well. “We did a lot of work together when I came to Chicago to the Regal Theater,” says Michael Henderson, who played bass with the Davis lineup in the ’70s. “Pete was in the house band there with [jazz drummer and bandleader] Red Saunders. He was also in the Pharaohs with Louis Satterfield—and that was the precursor of Earth, Wind & Fire.”

But there was a lot more to Cosey than blues and R&B. “I have a great appreciation for Kenny Burrell, Joe Pass, Tal Farlow, Grant Green,” he told Cole. “I loved Wes Montgomery. To listen to my playing, you wouldn’t imagine that I had been through that kind of music, but man, I used to play Wes stuff up and down.” That knowledge came in handy when he joined up with saxophonist Gene Ammons. “He definitely had to play bebop,” says David Liebman—the sax player and flautist with Cosey in Davis’ band—regarding Cosey’s role in the Ammons band. “Pete could do a lot of things. He seemed to be a well-schooled guy.”

Experimental guitarist Henry Kaiser also notes that Cosey was a virtuoso in multiple complicated genres. “Pete Cosey had many different systems of music,” Kaiser says. “He understood Asian music, Indian music, 20th-century classical music, and many different kinds of harmony and ways of organizing melody, harmony, and pitch. He used all of those tools—a very wide set of tools—wider than most people would use.”

Cosey was also an early member of the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM), a Chicago-area collaborative that included Muhal Richard Abrams, Henry Threadgill, Anthony Braxton, Jack DeJohnette, the Art Ensemble of Chicago, and many others on the frontiers of jazz and modern original music. That involvement with his city’s avant-garde scene, together with his background in blues, funk, and jazz, made him an ideal candidate to work with Miles Davis.

The Miles Years

Cosey started working with Davis in 1973. At the time, Davis had Indian musicians on sitar and tabla, but he streamlined the ensemble soon after Cosey joined. “The Indian instruments lasted another month or two, and then Miles cut the band down,” says Liebman. “He even got rid of the keyboard—he played keyboards himself when he wanted them.”

Davis’ Cosey-era band was a cultural statement as well. “Miles gave me three directions while I was with him,” Cosey told Cole. “The first was to move up front … [the second was] to turn up [the volume] … And the third thing he said was, ‘Sit there and look black!’”

Gibbs adds some nuance to that. “Miles really wanted to make the band black, and that was Pete’s thing in Chicago. His function was basically to bring what my friend [founding Black Rock Coalition member] Greg Tate calls ‘African continuum’ into the band. Obviously [percussionist] James Mtume had already brought that in, but Pete was like the final touch.”

Davis’ music at that point was slowly evolving toward lengthy funk grooves and structured group improve, and was influenced by artists as disparate as Sly Stone and Karlheinz Stockhausen. The band was loud and funky, and Cosey’s job was to add an element of Hendrix. “Since I couldn’t get Jimi or B.B. King, I had to settle for the next best player out there,” Davis wrote in his autobiography. “Pete gave me that Jimi Hendrix and Muddy Waters sound that I wanted.”

But aside from using distortion and wah-wah, Cosey didn’t sound anything like Hendrix. “Pete was Pete. Pete would have existed if Hendrix didn’t exist,” Gibbs says. “You listen to the little things he did—you take Chicago, electrify it, add some of the things he was doing on the jazz side, fuzz it up—and you’re going to get Pete.”

For one thing, Hendrix and Cosey had very different approaches to tone. Hendrix cranked his amp and pushed a lot of air. He used pedals as well, but his amp was central to his tone. Cosey’s approach was the opposite. “Pete knew how to get all these sounds at a very low volume,” Kaiser says. “He used pedals more than the amp to get his sound. He knew how to misuse pedals, too, like plugging the chord halfway in to get what we think of as Fuzz Factory-type sounds now. He knew the difference between having the fuzz before and after the wah. He had all the pedal tricks figured out.”

Cosey didn’t travel with an amp, though he had his preferences. “I liked the Yamaha equipment best,” he explained to Milkowski. “It gave me more highs, as opposed to the meatier sound you get with Marshalls. The Sunns were really powerful and sounded good, but the Yamaha equipment seemed to work best with my pedals.”

According to Henderson, Cosey sounded like Cosey regardless of the gear. “He could duplicate that sound through any amp,” Henderson says. “Once you know what your sound is, it’s not really about the amp that much. You are the instrument, and your tone and your sound on whatever you play is going to have that same attitude—even if you’re tapping on the table. His DNA, so to speak, generated what you heard out of the speakers.”

Another distinguishing feature of Cosey’s playing was how he tuned his guitars. “He never played in standard tuning,” Henderson says. “He would tune to the way he wanted to play the chords—the way he wanted them to sound—because the different tunings make your approach quite different.”

Miles Davis (third from right), Pete Cosey (far left), and the band chill with food and beverages in this circa-1970s photo.

Photo courtesy of Miriama Cosey

Gibbs laughs as he recalls his experiences with Cosey and tunings. “Pete had, like, a gazillion tunings—which he didn’t share! He used different tuning systems for different songs, and that was an integral part of his approach. We did some gigs where I didn’t send him the music ahead of time. I realized later that he wanted music ahead of time so he could listen to everything and adjust it to his tuning systems.”

Cosey even reserved different guitars for special tunings, although he wasn’t able to travel with all of them. “He tried to bring a lot of guitars with him on tour, but he couldn’t get them all on the plane,” Henderson says. “Miles cut him down to three. He had to reserve extra seats. Pete was a big guy, so he would have to have two seats for himself, then he would get extra seats for his guitars—and he had his pedals with him, too. There was no way you were getting him to put his instruments underneath the plane.”

A number of Miles Davis albums feature Cosey’s playing, the most significant being a trio of live albums—Dark Magus, Agharta, and Pangaea. The latter two were the afternoon and evening performances, respectively, from a single day in Osaka, Japan. Many critics consider Agharta the better album and praise Cosey’s exceptional playing on it as an example of instrument mastery, as well as a study in contrasts. He’s insanely fast at times, tasteful and atmospheric at others. He employs intense chromaticism and dissonance, yet is firmly grounded in the blues. His sense of phrasing is blistering and in your face, but somehow also restrained. He uses a small army of effects—a huge innovation for the time—and is in complete control of his feedback. His sonic sense is outstanding and totally original.

“He was like a funny combination of really bluesy shit and out stuff,” Liebman says. “He sat there with a table and all these pedals. He had the ability to make some really different kinds of sounds.”

Milkowski wrote that although Cosey played a variety of guitars during the Miles years, he primarily played an SG-like Guild for Agharta and Pangaea, and ’54 and ’59 Gibson Les Pauls for Dark Magus. He kept a ’61 Strat in reserve, just in case. A trademark of Cosey’s stage setup was a table loaded with assorted percussion instruments. He sat behind the table and put his effects—two wahs (a Morley for warm tones, a Halifax for solos, and sometimes a Vox Clyde McCoy), a Jordan Bosstone for dirt, and a Gibson pedal—underneath it. He also often used an EMS Synthi A synthesizer.

“Pete would try everything,” Gibbs says. “Every time I was with Pete he was trying a different guitar—he had, like, a Spinal Tap level of guitars. He had many different pedals, too, but he had a range of sound that he liked.” Cosey also used a Vox Phantom XII electric 12-string and a Morris Mando Mania guitar, among many others. “Another thing that’s really interesting about Pete is that he was one of the first people to mess with guitar synths,” Gibbs adds. Years later, in addition to the EMS Synthi A, he also had a headless Ibanez MIDI controller, a Roland guitar-synth controller, and a Yamaha TX81Z.

Post-Miles Pete

In 1975, Davis broke up the band and began a five-year hiatus from music. He and Cosey stayed in touch and did various sessions together, but for the most part Cosey stayed in Chicago and worked on other projects. He appeared on Herbie Hancock’s groundbreaking 1983 album, Future Shock. In addition to being a platinum-selling success, the album was revolutionary in its use of drum machines and record scratches, and it dominated MTV. The guitar solo on the title track, despite the serious ’80s surroundings, is classic Cosey—wide intervals, twisted dissonance, subtle whammy use, and unorthodox tones that stick out like thorns from a mix that otherwise conjures visions of badly-dancing club goers in pastel-shaded blazers with shoulder pads.

Cosey didn’t record much in the ’80s and ’90s, but he stayed busy leading various projects, teaming up with drummer Buddy Miles (Hendrix/Band of Gypsys), and working with Gibbs. “Pete became a member of the group Power Tools, which was myself, Ronald Shannon Jackson, and originally Bill Frisell,” Gibbs says. “Bill moved on, so we got Pete to come in.”

Gibbs used Cosey for a number of projects over the next 20 years, including a spectacular solo on “Canto por Odudua” from Gibbs’ 2012 Elevated Entity album, Ancients Speak. Cosey’s solo is what you’d expect—overdriven, dissonant, idiosyncratic, yet complementary and song appropriate—proof that despite a dearth of recorded output, the master still had it. And Gibbs has a backlog of recordings set for release. “We did a whole session based around the [1970 Miles Davis album] Bitches Brew,” he says. “I had a bunch of musicians play along to the original recording. I then took the original record away and mixed what they had played to it. Pete sounds great on that.”

Cosey was involved in many other projects, including the aforementioned “Godfathers and Sons” documentary episode, Greg Tate’s 2003 Burnt Sugar version of Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring (conducted by Butch Morris), and free-jazz saxophonist Akira Sakata’s 2001 album Fisherman’s.com.

YouTube It

Miles Davis leads his band through a live performance of “Ife” in this 1973 footage. Check out Pete Cosey’s remarkable eclectic solo just after the five-minute mark—it goes from mellow, approachable jazz to nastily discordant and fuzzed-out wailing high up on the neck.

He led groups that included Gibbs, drummer JT Lewis, and DJ Johnny “Juice” Rosado (Public Enemy). He was also involved with educational programs as part of the Jazz Foundation’s Agnes Varis Jazz and Blues in the Schools program.

Cosey kept Davis’ music alive as well. He performed with Gibbs at the Davis tribute Wall-to-Wall Miles, and formed the group Children of Agharta to record and perform with the Grammy-nominated project Miles from India. “He had me come sit next to him during the long rehearsal,” says Kaiser—who subbed for Cosey on some live Miles from India performances that Cosey missed for health reasons. “He explained everything he was doing to me so I would know in case I had to substitute again. It was amazing to get to do that with one of my heroes.”

True to the End

Cosey was a powerful spirit. “I’ve had the opportunity to be around a lot of singular, influential people,” Gibbs says. “People like Ornette Coleman, Gil Evans. Pete was one of the most influential—without being influential—people in my life. He’s known because he made other people’s music happen: He made Miles’ music happen … he was part of that great Chess band. But a lot of his information is filtered out as being other people’s information.” He knew how to process his influences, internalize them, and make them his own. “Like I said, Pete would have existed even if Hendrix didn’t exist. Pete took that same pool of information and made a natural progression.”

Cosey told Cole, “I wasn’t living an easy life. I went through a lot of great struggles but I kept true to the music. I never lost sight of that. I never stopped experimenting, improving, and crystallizing, and creating, and I still do that. I realized a long time ago what my mission is and I’ve stayed true to that.”

Health issues became an increasingly difficult struggle for Cosey near the end of his life. According to the Chicago Tribune, he died of complications from an undisclosed surgery on May 30, 2012. He was 68. He left behind a legacy of incredible playing and a core group of people who loved him.

“If you learn anything from his playing then you learn something about the man,” Henderson says. “Pete Cosey was a way of life. He was a good man—he knew how to live—and you heard it in his playing.”

“He never played in standard tuning. He would tune to the way he wanted to play the chords—the way he wanted them to sound—because the different tunings make your approach quite different.” —Michael Henderson

Hallmarks of Cosey’s Style

Miles Davis went modal with his landmark 1959 release Kind of Blue. Based on the modal theories of composer and theorist George Russell, the music eschewed jazz’s traditional reliance on a never-ending succession of chord changes as the basis for improvisation. Instead, improvisers were given the freedom to explore and experiment within the context of a static mode or chord-scale.

Early modal compositions like Davis’ “So What” and John Coltrane’s “Impressions” still relied on a recognizable AABA form, but by the early ’70s, Davis’ music—inspired by musicians like Sly Stone and James Brown—sat on one groove, usually an ostinato bass line, which went on ad infinitum. “It was all vamps,” says David Liebman, who played sax with Miles during that time. “Miles had maybe a two-bar or four-bar riff, but it was really vamp music and soloing over the vamp.” During Pete Cosey’s tenure with Davis, it was not unusual for songs to go on for 20 minutes or more.

Davis experimented with complex rhythmic theories at that time as well. He assigned different instruments grooves to play in unrelated time signatures. Those grooves linked up every X number of bars, depending on how the various time signatures cycled in relationship to each other, and created intense polyrhythms in the process. But the harmonic setting was loose and gave the improviser incredible freedom to flourish.

It was a setting well suited for a player like Cosey. With his background in the blues and jazz—as well as funk, free, and various world-music genres—he had the awareness and experience to create soaring, open-ended melodic conversations. “Pete’s role with Miles was to do whatever he felt like—whatever he felt like was perfect,” Melvin Gibbs says. “Miles cued the band and it became the Pete show for about a half an hour after that.”

But modal playing is a far cry from easy. Although making complex, moving chord changes is challenging (try playing “Giant Steps” at breakneck speed), developing themes and ideas—without aimlessly wandering—is daunting as well. Cosey’s genius was his ability to thrive in that environment. He developed complex themes and variations and was a master of tension and release. He didn’t ramble and he kept the listener engaged. To hear him in action, check out the version of “Ife” and “Prelude (Part I)” from Agharta.

While playing with Zappa and Beefheart, this blues guitarist pushed the limits of traditional form within avant-garde rock.

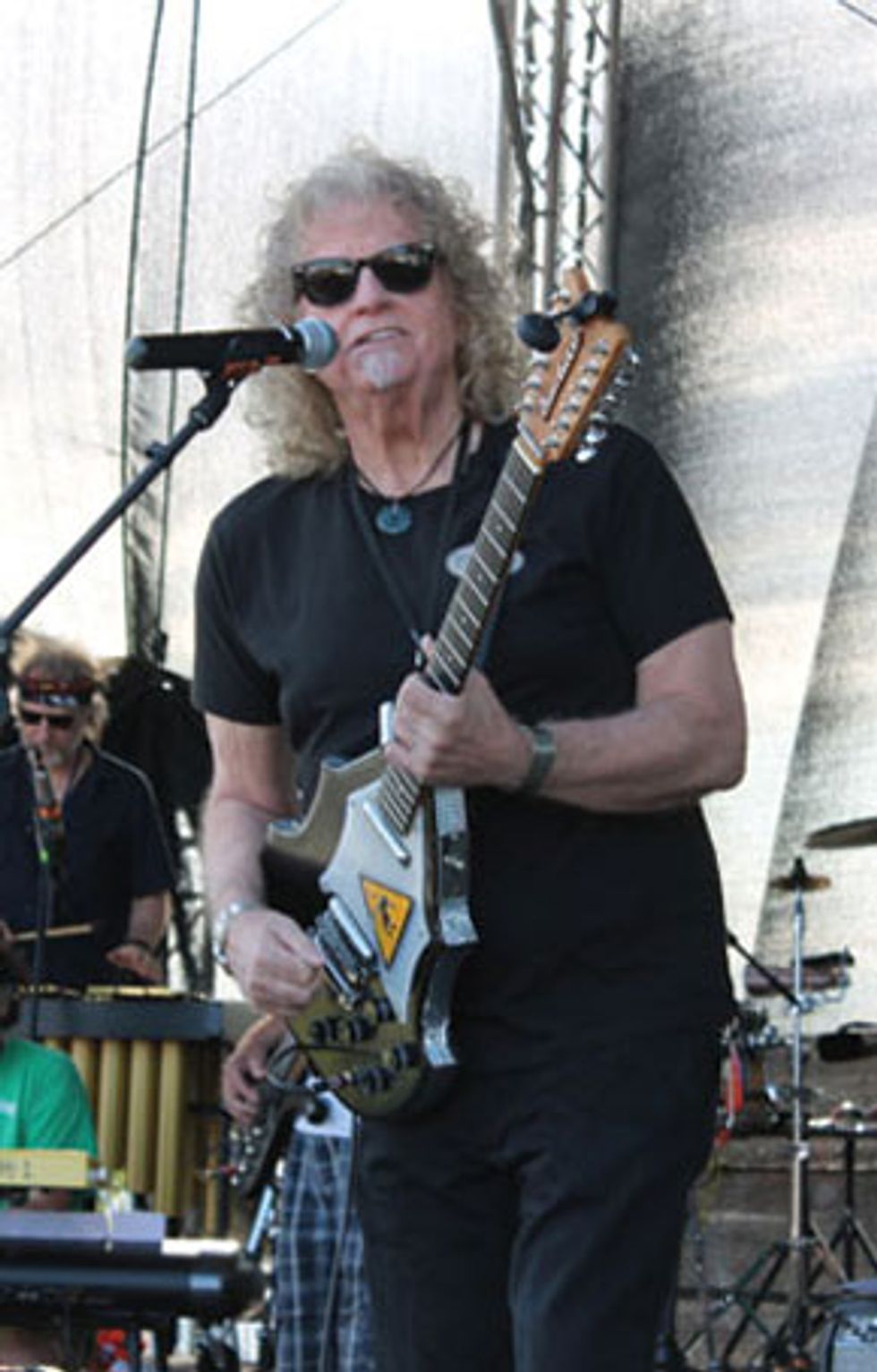

Denny Walley isn’t a household name—but he should be. His exquisite slide work and powerful vocals are integral to classic Frank Zappa albums like Bongo Fury, Joe’s Garage, You Are What You Is, and others. He had a similar role in Captain Beefheart’s Magic Band. (His Beefheart alias was “Feelers Rebo.”) He toured extensively with Beefheart, and his guitar appears on the often-bootlegged 1978 classic Bat Chain Puller. But Walley’s work isn’t limited to the esoteric or avant-garde. He spent years as a sideman immersed in soul, funk, R&B, and blues, and nearly hit the big time with the hard-rocking Geronimo Black.

But Walley’s most important accomplishment may be his ability to straddle those dissimilar worlds. Regardless of context—be it far-out, contemporary, traditional, or mutant hybrid—Walley speaks in a unique voice. And that voice, whether quoting one of his heroes or interpreting the visions of a mad musical genius, helped redefine what the guitar can do.

The septuagenarian still does what he does best: straddle disparate styles, pay homage to his mentors, and forge ahead with his creative blend of traditional and not-so-traditional music. Premier Guitar spoke with Walley via Skype. Our conversation (plus archived interviews and many hours of classic performances) paints an illuminating picture of an important and underappreciated guitarist.

Beginnings

Denny Walley was born in Pennsylvania in 1944. His family moved to Brooklyn when he was a toddler and then to Lancaster, California, in the mid-1950s, when his father, an aircraft mechanic, was sent to work at Edwards Air Force Base. The move was a good one. “I was 12 going on 13, and we moved into the same housing development that Frank Zappa lived in,” Walley says. “I became best friends with Frank’s brother Bobby. We had a common interest in blues records—the early blues 45s—and Frank was a big collector. I would go over there and Frank would play those records.”

Walley’s first instrument was the accordion. He started lessons at age 7, but he says that ended when he discovered the blues: “After hearing the guitar on blues, and hearing men sing with passion—men who weren’t afraid to be passionate and sensitive—I said, ‘Damn. I didn’t know men could do that.’ The accordion went under the bed, never to be seen again.” (Well, almost never: Walley played accordion on “Harry Irene” on Captain Beefheart’s Bat Chain Puller.

Walley finished two years of high school in Lancaster before his father was transferred again. Back in New York—smitten with the blues and desperate for friends—he set up his speakers facing the street, cranked old blues records, and prayed for a kindred spirit. He was in luck. Another blues fan lived across the street. Walley fell in with the local blues hounds, and he and his new friends played along with records, trying to decode the music. Walley got his first guitar: a Silvertone Stratotone. “It was a single-cutaway sunburst with binding,” he recalls. “I polished that thing every day. I slept with it. I played it until my fingers blew up like plums—there was no such thing as light-gauge strings back then.”

Walley played his first gigs while still in high school, alongside bassist Tom Leavey (his future brother-in-law). They continued after graduation, spending most of the 1960s performing at clubs in and around New York and touring nationally as the Detours. “I’d lost connection with the Zappas,” says Walley. “The next time I saw Frank was when I was playing with the Detours in Greenwich Village. It was the same time that Frank was playing at the Garrick Theater. I went over and saw Bobby Zappa in the lobby. I told him I’d love to see Frank.”

Walley and Captain Beefheart onstage in 1976.

The Village at that time was an epicenter of late-’60s counterculture. The vibe was heavy, and Zappa was an established figure. Walley went to visit him still dressed for work with the Detours—tuxedo, cufflinks, pinky ring—in other words, clean-cut and square. He didn’t look cool—and Zappa didn’t even know he was a musician. “I went upstairs and saw Frank,” Walley remembers. “He was with Allen Ginsberg, Tuli Kupferberg from the Fugs—all these deep thinkers. I walked in and said, ‘Hey Frank, remember me?’ Oh God, was that awkward.”

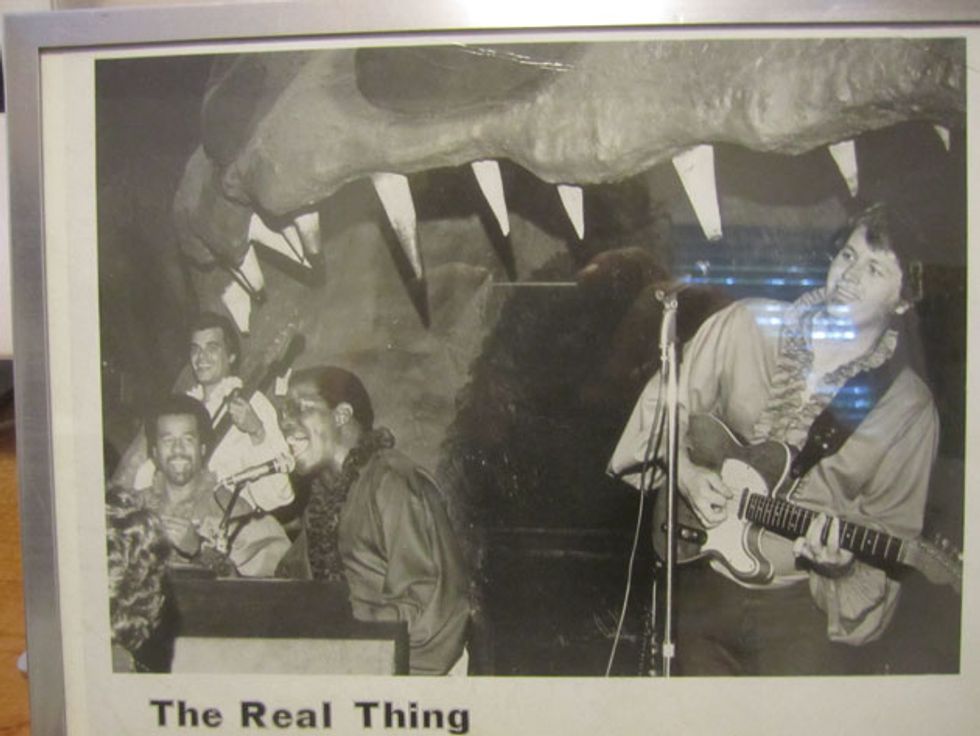

In late 1969, Walley moved to Los Angeles and quickly found work. He replaced Al McKay—the future guitarist for Earth, Wind & Fire—as the guitarist in the Real Thing. That band played soul and R&B, working six nights a week as the house band at the Haunted House, a popular Hollywood nightclub. That led to studio work, gigs backing the Valentinos (the Womack Brothers) and gospel singer Andraé Crouch, and tours supporting such entertainers as Rosie Grier and Bill Cosby (as a member of Cosby’s Badfoot Brown & the Bunions Bradford Funeral & Marching Band).

Geronimo Black

Meanwhile, Tom Leavey had moved to Los Angeles and joined Geronimo Black, the band drummer/vocalist Jimmy Carl Black assembled after Zappa disbanded the original Mothers of Invention. Geronimo Black needed a guitarist, and Leavey recommended Walley. “I met them and we clicked right away,” Walley says. Geronimo Black was hard-rocking and hard-living. They signed with Universal Records, and their first album was produced by Keith Olsen, who would go on to produce Fleetwood Mac, the Grateful Dead, and many other artists. Walley played his ass off. Of note is his raunchy, wah-infected, blues riffage on “Low Ridin’ Man,” the opening track from the group’s 1972 self-titled album debut—and a testament to the band’s power, heavy rumble, and swagger.

But Geronimo Black was doomed from inception. “Russ Regan signed us,” Walley recalls. “We had high hopes and the label did as well. We were wild, but Russ knew how to handle us. After about a month, Russ left Universal to head up another label. No one knew what to do with us—they were afraid of us. We had a few incidents: We might have been a bit drunk and sort of crashed a party for Elton John and proceeded to drink all the beer and eat a mountain of jumbo shrimp before being asked to leave. Shortly after that we were recording at a studio on the UNI lot. It seems a ‘certain band’ purloined a golf cart belonging to one of their major stars, and a drunken joyride resulted in the cart getting trashed. After that they wouldn’t even let us on the property anymore. So we didn’t last long.”

After the group disbanded, Walley went back to work in L.A. He continued with blues, R&B, and soul acts, working with King Cotton, the Kingpins, and others. Near the end of 1974, Jim “Motorhead” Sherwood—another old friend from Lancaster and a longtime Zappa associate—came to visit. “Motorhead said Frank was looking for a slide guitar player,” Walley remembers. “He told Frank about me. Frank had no idea I played because when he knew me in high school, I wasn’t playing yet. So Frank says, ‘Tell him to come on by tomorrow.’”

Zappa and Walley, onstage together.

Zappa Round One

Zappa was preparing for the Bongo Fury tour and subsequent album. The project was a collaboration with Captain Beefheart (Don Van Vliet), another Lancaster alum. Why was this small town such an avant-garde breeding ground? “I think something flew very low over Lancaster,” says Walley. “They were doing a lot of experimentation out at Edwards Air Force Base.”

Slide guitar was an obvious timbre choice for a Zappa lineup featuring Beefheart. It conjured serious blues mojo and complemented Beefheart’s blues-influenced style. But Walley hadn’t seen Zappa in years, and by 1974, Zappa was an institution. Walley was ready for his audition, but nervous. “I walked in the door and could’ve dropped to my knees,” he says. “George Duke was on keyboards. Tom Fowler was the bass player. Chester Thompson was behind the drums, plus Napoleon Murphy Brock and Frank. That was what I walked into.”

The audition couldn’t have gone better. “Frank introduced me to everyone and it was real relaxed. He was so disarming. Frank called ‘Advance Romance.’ I’d never heard it before, but it turned out they played it in A, and I had my guitar tuned to open A. As soon as I heard the beginning I started to shake, because I knew that this was so in my wheelhouse. It was like Frank wrote it for me so that I would pass the test. Halfway through, Frank stopped the song and said, ‘Anyone with balls enough to play those lows notes has got the job.’ That was it. I packed my stuff and went with [road manager Marty] Perellis into the office. He got my information and signed me up.”

Although Bongo Fury is still very much a Zappa production, Walley’s slide and Beefheart’s harmonica make it notably raw and bluesy—and weirdly accessible. And Walley’s playing shines. His fat tone and meaty slide on songs like “Advance Romance” and “Poofter’s Froth Wyoming Plans Ahead” (and his unusual note choices in the guitar’s lower register) create a heavy, earthy feel that stands in dramatic contrast to Zappa’s unorthodox phrasing and effects-drenched tone.

In retrospect, Bongo Fury is considered an important transitional album for Zappa. (Drummer Terry Bozzio replaced Chester Thompson soon after Walley joined the band.) But not everyone saw it that way at the time. As Gordon Fletcher noted in his Rolling Stone review, “In a year that’s seen the release of Lou Reed’s Metal Machine Music, it would be difficult to call Bongo Fury 1975’s worst LP, but … ”

The guitars Walley used during his first Zappa stint remained his mainstays throughout his career, and he still uses most of them. For slide work he favors a Vinnie Bell-endorsed Danelectro Bellzouki model 7020 from 1965—a 12-string with a bouzouki-shaped body. Walley installs only six strings and usually tunes to an open A or G, using a capo to play in other keys. He wears his slide on his pinky. “I can still hold a chord [with my other fingers] but move the slide,” he says. His slide—a metal tube made from the handlebar of a child’s bicycle—is the only one he’s ever owned. “I’ve had this my whole career,” he says. “If I lose it, the show don’t go on.”

His other guitars included a blond 1957 Strat—sold many years ago—and a heavily modified 1962 Telecaster bearing the signatures of Scotty Moore, Les Paul, and Link Wray. Its modifications include a 6-position, Gibson-style Varitone knob, an onboard preamp, and a revolving cast of pickups.

The signatures of Les Paul, Scotty Moore, and Link Wray grace Walley’s heavily modded Telecaster. The large black knob controls a Gibson-style

Varitone circuit.

Walley’s amp with Zappa was an Acoustic 150 head pushing an Acoustic 6x10 cabinet. “Frank wanted me to play through a Vox amp,” he says, “but I just didn’t like the tone. Even though the Acoustic was a solid-state amp, it had a tube quality. When you cranked it up, it had perfect distortion.” Walley says he used few effects: “I only used the pedals that Frank gave me to use, like a Mu-Tron that I used on a few things.”

Captain Beefheart’s Magic Band

Following Bongo Fury—and on Zappa’s recommendation—Walley joined Captain Beefheart’s Magic Band. Both the music and work environment were unlike anything he’d encountered. “I’d never heard Don’s music before,” Walley says. “Frank gave me Trout Mask Replica to listen to. I put it on and thought, ‘What? Where is my part? Where’s the beat? Where is anything?’ I could not listen with the right kind of ears—I wasn’t ready. Frank’s music was difficult, but there was structure to it. But in Don’s, nothing ever repeated. I listened and listened, and after the third or fourth time I realized, ‘God, this stuff is really just the blues.’ The blues thing was really thick in there, and his voice was amazing. So I decided to give it a shot.”

Walley was a member of Beefheart’s band from 1975 through 1977. They toured Europe and parts of the U.S. and recorded the album Bat Chain Puller, which, due to legal issues and other complications, wasn’t released until 2012. The album—viewed by some as a redemption following Beefheart’s mid-’70s “Tragic Band”—features Walley throughout, notably his stellar slide work on “Owed T’Alex.” Not featured on the original release—although now available for download on iTunes—is the Beefheart/Walley duet “Hobo-Ism.” It’s a mesmerizing blues jam featuring Walley’s acoustic guitar and Beefheart’s raw, uncompromising vocals and harmonica. “It was a one-off, stream-of-consciousness thing that happened in my living room,” Walley says.

But Beefheart’s free spirit, disorganization, and cult-like authoritarian style made Walley’s tenure difficult. “Don used to do this thing where he would play one guy against the other. He would say thing like, ‘Hey man, somebody is thinking C, and you know who you are,’ which would immediately send everyone into defense mechanism. You’d start defending yourself against the indefensible, and this would go on for hours.” Rehearsals were sometimes 14-hour ordeals that didn’t involve playing. Beefheart was brilliant and creative, but difficult and easily distracted. The work environment was frustrating, especially since the band wasn’t getting paid. Walley, not one to be pushed around, stood his ground—maybe one time too many—and was given the boot. “Someone in the band was elected to make the call,” he remembers. “He told me, ‘You’ve made your bed. Now you have to sleep in it.’” But despite his departure, Walley remained on good terms with Beefheart. “In fact,” he says, “after that is when we did ‘Hobo-ism.’”

How come they don’t make stages like that anymore? The Real Thing captured live at Hollywood’s Haunted House club in 1970. (Left to right: Kent Sprague, Ray Hosino, Stu Gardner, Denny Walley.)

Return to Zappa

Following Beefheart, Walley went back to working with Zappa, joining his touring band and working with him in the studio. Walley appears on Joe’s Garage, Zappa’s satirical rock opera in three acts. “All the background singing is just Ike [Willis] and me, doubling and tripling our parts.” Walley appears on many other Zappa albums, both studio compositions and live recordings.

“Frank recorded every concert with his own guys on his own gear,” says Walley. He recorded rehearsals as well. Whole songs, sections, and solos might be taken from live recordings and inserted into other songs or incorporated into albums. A musician’s work could end up on a Zappa album at any time, even years later. “Frank was the master of compilations,” says Walley. “As a result of that I wound up on about 19 or 20 albums.”

Zappa had such flexibility because his band was so well rehearsed, and much of what he recorded was perfect. “It was so accurate,” Walley says. “For example, he was able to take a section of music from a song that was recorded in Chicago and use that with a recording from Pennsylvania. The tempo, the EQ—everything would be right. You could put it right in.”

On tour, the band rehearsed daily during soundchecks, which usually lasted two or three hours. This constant rehearsal kept the band on its toes. “Frank had about 50 hand signals, and each one had a specific purpose. You would get the song and the key—if there was a key change—or if there was a modulation or a crescendo or decrescendo. He read the audience. He saw what kind of reaction he was getting, and he could change the set anytime he wanted because we were already preloaded for that.” New material was constantly introduced. “Frank would hear things—or maybe a mistake or something would happen—and he would say, ‘Put that in.’”

One song—“Jumbo Go Away,” from the album, You Are What You Is—was written on tour about a female stalker obsessed with Walley. “She would show up everywhere, no matter what city. One night as we were rolling into the hotel—Frank was with us—and were waiting for the elevator, and there she was. I turned around and said, ‘Jumbo, go away.’ The next day at soundcheck, Frank handed me the words to a song he wrote called, ‘Jumbo Go Away.’ We learned that song at soundcheck and did it that night. Things like that happened all the time.”

Post-Zappa

Walley was a fulltime member of Zappa’s band until mid 1979. After that, he did session work and gigged around L.A., but didn’t join another touring band. “After a while I figured, ‘You know what? Maybe I should get a job,’” he says. He worked for a scenery company in Hollywood and then started sculpting and doing projects for amusement parks. He played locally, but didn’t tour.

A recent picture of Walley with his favorite slide guitar: a vintage Danelectro Bellzouki. It’s a 12-string model,

but Walley uses only six strings.

Walley’s solo recording output is sparse. He released a 45—“Who Do” backed with “Tiny Tattoo”—in the late-’70s with a band that features Zappa bandmates Tommy Mars, Ed Mann, and Vinnie Colaiuta, among others. He recorded a solo album, Spare Parts, in Sweden in 1997. “I did a tour with [Swedish duo] Mats/Morgan,” he says. “We were playing blues stuff and originals. At the end of the tour, Morgan [Ågren] asked, ‘Why don’t you record an album while you’re here?’ So we recorded the songs we played on the tour.”

Despite doing little recording, Walley hasn’t stopped playing. These days he’s back to making music fulltime. He recently finished a 13-year stint with the reunited Magic Band. He tours with Zappa tribute bands in Europe and the U.S., sits in with Zappa Plays Zappa, leads his own band, and creates new music. “I’ve been playing Frank’s music and Don’s music all these years, and I love doing that,” he says. “But I love playing. I don’t want to wait around for someone to want me to play with them. I want to play with me, too.”

Without much fanfare or glory, Walley had a major impact on contemporary guitar. He was a student of the early blues and is a master of the style. His long career with some of his generation’s most radical musical thinkers—plus his own innate curiosity and openness—helped redefine how the guitar is played. Walley showed just how far you could expand traditional forms and push the limits of what is considered “listenable.” And he did all of that with a foot firmly planted in traditional music and tone.

And he’s still doing it. “I’m not going to stop playing,” says Walley. “I’m basically playing music for me. But if you enjoy it, all the better!”

Geronimo Black in 1973. (Front row, left to right: Bunk Gardner, Jimmy Carl Black, Tom Leavey, Denny Walley. Rear, left to right: Andy Cahan, Tjay Contrelli.)

Hallmarks of Style: The Slim Harpo Effect

How Denny Walley maintained a blues identity in a non-blues idiom.Despite being idiosyncratic composers, Frank Zappa and Captain Beefheart gave their sidemen much creative space. Denny Walley explained some of the elements of his blues style and why it worked within avant-garde rock bands.

Did Zappa give his sidemen a lot of freedom?

Frank hired people not so much for their ability, but for the way they interpreted and heard his music. When you write something on paper, you know tonally what it should sound like, but it sounds different when it interacts with other people’s emotions. You can play a note on your guitar and then give me your guitar. I’ll play the same note, but it won’t sound the same as your note. It’s in your hands. You are the delivery system.

So he picked people for their delivery systems?

Obviously, because I was nowhere near the virtuosity the other guys had in their realms. When I played with Frank, the music dictated the type of playing. I would not be in one of his classical bands because I can’t read that well. He didn’t tell me what to play, and he didn’t tell me to stop playing. He gave me an amazing amount of freedom.

It seems like Zappa gave you more tonal leeway than Beefheart. Did your personality still come come through in the Beefheart material?

Oh yeah. In fact, more than one person has said the material on Bat Chain Puller was the first time that Beefheart would be accessible to everyone without disappointing Beefheart fans—and they point out the slide guitar. My approach and style and influence—from all those blues guys—is where I live. I can’t play 64th notes. I probably could if I tried, but I don’t care about them. Take the Slim Harpo solo on “I’m a King Bee.” It’s one note. He plays it four times and that’s it—but it’s the tension in between. It’s where you don’t put the note, and how serious you are about that note. I like the economy of that. It’s stripped down to the essence of the note’s emotion. That’s what I do. I’ve probably played the same thing on every song I’ve ever played on. But it just seemed like it needed it.

I don’t think that’s totally fair. I watched live Zappa clips, and you and Ike Willis play some difficult unison lines. You can do all that stuff, too.

I can do it if I’m forced to. But left to my own devices, it’s not going to happen. It’s not my style. I appreciate that style, but I don’t hear it. For me, that part would never come into my realm of thinking. I can play it, but I never would have conceived it.

YouTube It—Essential Listening

“Advance Romance” from Bongo Fury was Denny Walley’s Mothers of Invention audition song. His iconic slide solo starts at 2:40.

Check out Denny Walley and the Muffin Men’s amazing rendition of Captain Beefheart’s “Suction Prints” at the Zanzibar Club in Liverpool, England, in 2013. Walley demonstrates his slide virtuosity right out of the gate.

A rehearsal for a 1978 Frank Zappa and the Mothers of Invention show in Germany. Zappa introduces his brilliant lineup, including Denny Walley, at 5:35.

This audio clip of Geronimo Black’s “Low Ridin’ Man” showcases Denny Walley’s righteous wah work.

The gospel guitarist who took his tremolo-shaken country blues from Sunday mass to the masses.

Whenever you hear country blues-inflected guitar played through an amp with tremolo, you’re hearing a sound descended from singer/composer/guitarist Pops Staples. Best known as the leader of a family gospel group, the Staple Singers, his guitar style influenced and inspired John Fogerty, Bonnie Raitt, Ry Cooder, and countless others. The dark mystery of his instrument’s wavy sound has become part of the fabric of American music.

Roebuck Staples, known as “Pops,” was born to Warren and Florence Staples on December 28, 1914, on a cotton plantation near Winona, Mississippi. Roebuck and his older brother Sears were named after the Chicago mail-order company that supplied millions of rural Americans with everything from washing machines to musical instruments.

The Staples soon moved to a plot on the Dockery plantation near Drew, Mississippi. As a teenager, Staples would make money participating in local boxing contests, but other interests had already begun. Though secular music was forbidden in his family, his brother David played blues guitar. By age 14 Staples was paying fifty cents a week towards a Stella he saw hanging in a store window. Like many blues artists of the time he picked cotton during the day, but when work was done he’d commune with the guitar, taking it to bed and playing under the covers as long as his father would allow.

—Leroy Crume

In Drew, he heard blues legend Charley Patton, who played at a local hardware store in the evenings. The sight of Patton, Howlin’ Wolf, and others making a living playing music inspired the young Staples to practice. By age 16 his diligence paid off with party gigs on the plantation circuit. The house manager collected contributions from the attendees, sometimes paying the guitarist $5 a night—a fortune by sharecropper standards.

Despite his love of the blues, Staples remained involved in the religious community, singing in church and later touring with a gospel quartet, the Golden Trumpets. At the time the guitar was associated with “the Devil’s music” and forbidden in churches, though Staples never saw the contradiction—he felt the blues were just telling a different story.

Citified

At 18, Staples married 16-year-old Oceola Ware. A daughter, Cleotha, and a son, Pervis, soon followed. Seeing no future for his family in the South, he journeyed to Chicago. There, Staples put the guitar down for a dozen years while working in a slaughterhouse and a series of other jobs. Oceola worked as well, and gave birth to two more daughters: Yvonne and Mavis.

The Staple Singers pose with Don Cornelius (right) on the set of Soul Train. This publicity photo was taken during production of the June 8, 1974 episode.

Chicago in the ’40s was a hotbed of R&B, blues, and bebop. The Staples family lived in the neighborhood that spawned such talents as Lou Rawls, Sam Cooke, and Johnny Taylor. Gospel was also on the rise, with guitar-based male quartets and piano-accompanied female soloists working a circuit of churches around the nation.

For a while, Staples joined the Trumpet Jubilees as a vocalist, but in 1948 he decided to form a group closer to home. He pulled out an old guitar and taught Mavis, Cleotha, Pervis, and Yvonne harmony parts to “Will the Circle Be Unbroken.” The family’s debut at an aunt’s church brought seven dollars and promises of more gigs. The Staples warm Southern sound quickly caught on, and soon they were branching out to other cities and states.

In 1950 Staples bought his first electric guitar, an amp, and the tremolo effect that would help define his sound. Pops played a variety of mostly Fender guitars throughout his career: Telecasters, Jazzmasters, Jaguars, and Stratocasters. In Greg Kot’s book, I'll Take You There: Mavis Staples, the Staple Singers and the March Up Freedom's Highway, Sam Cooke’s guitarist Leroy Crume recalled: “When Pops came on the scene, he brought this little gadget you put on an amplifier—at the time they weren’t making amps with tremolos … People used to call it ‘Pop Staples and his nervous guitar.’” The effect was most likely a DeArmond 601 Tremolo unit, which became available in 1948.

Though Pops Staples never left the church, he’d spent his fair share of time in juke joints playing the blues. With his family band committed to gospel, he now joined a Baptist church and was “born again,” giving up secular music for the moment.

In 1953, Pops had the newly named Staple Singers record a single to sell at shows. A Chicago label, United Records, soon signed them, but their first label record, “Won’t You Sit Down (Sit Down Servant),” failed to hit. An early version of “This May Be the Last Time” (later covered by The Rolling Stones as “The Last Time”) was cut but not released until years later, and on another label. United wanted the band to move in a more rock ’n’ roll direction, and for Mavis to sing the blues. Pops refused to agree.

It was back to the factory for a while, but the Staple Singers’ singular sound—14-year-old Mavis’ low voice, Pops’ falsetto, and country soul in an urban environment—couldn’t be denied. Another part of their unique appeal was Staples’ guitar. Though artists like Sister Rosetta Tharpe and Pops’ favorite, Blind Willie Johnson, had incorporated guitar into gospel, the Staple Singers were one of the first Chicago gospel groups to employ this previously shunned instrument. They were allowed to enter local churches that had previously permitted only keyboard accompaniment.

Vee-Jay Days

In 1955, the Staple Singers’ worth was recognized by Vee-Jay records (who later recognized the Beatles’ talent, distributing their records in America when Capitol initially refused). After a couple of false starts, they released the haunting “Uncloudy Day.” It became the Staple Singers’ first hit (at least by gospel standards) and allowed them to begin touring nationally.

Part of the Staples’ appeal lay in a down-home sound and attitude that reminded Northern urban churchgoers of their rural Southern roots. The Staples’ stripped-down performances—just Pops’ guitar and their voices—stood in stark contrast to the more flamboyant gospel acts of the day.

Pops’ playing is the foundation of the tracks the Staple Singers cut for Vee-Jay between 1955 and 1961. As Greg Kot describes it in his Staples book: “His style created an atmosphere that was immediately distinctive, a hypnotic swirl of reverb, repetition, and riff. Chords were implied as much as articulated, notes were blurred, tones and overtones were carefully layered like the bricks Pops used to cement into place at his construction jobs.”

While the Staple Singers’ repertoire wasn’t strictly gospel, identifying themselves with that genre gave them an advantage over R&B groups: They could play hundreds of small churches across the country, sometimes doing two or three services a day at a single church. Like many R&B artists, though, Staples carried a gun in his briefcase to ensure payment by crooked promoters and to protect the money afterwards.

In the 1960s, the Staple Singers moved to Orrin Keepnews’ jazz and folk label, Riverside Records. Keepnews added more prominent bass and drums to their recordings, helping them extend their audience beyond the church while remaining true to their homespun roots.

The group managed to fit into the “folk” music revolution of the ’60s, often crossing paths with Bob Dylan on TV shows and at festivals. The fledgling legend was a huge fan—to the point of asking Mavis to marry him. The group recorded “Blowing in the Wind” for Riverside before Dylan’s own version hit the streets.

Pops often found folk music’s message to be in tune with his family’s ideology. Dylan’s music, and a meeting with Martin Luther King, Jr., inspired him to record songs reflecting the civil rights and anti-war movements for their record This Land.

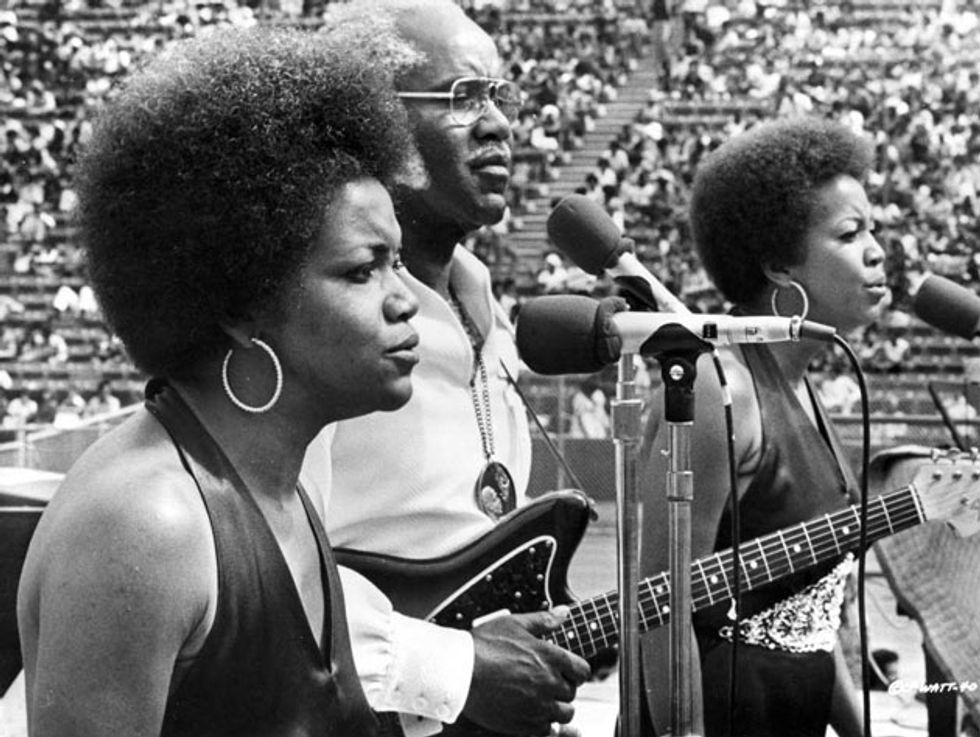

Cleotha, Yvonne, and Mavis Staples (left to right) are the female vocalists of the Staples Singers. The first song their father, Pops Staples, taught them to sing harmony on was “Will the Circle Be Unbroken.”

Freedom Highway

In 1965, the Staples signed with Epic and recorded with producer Billy Sherrill. Sherrill was known for creating the “countrypolitan” sound of artists like George Jones and Tammy Wynette, but had started in music playing the blues.

That year also brought the famous Selma to Montgomery civil rights march. Pops Staples, upset by the images of clubs, dogs, and tear gas, was moved to write his iconic song “Freedom Highway.” The group performed it for the first time at Chicago’s New Nazareth Church, where Sherrill recorded the entire performance for the live Freedom Highway record. Al Duncan on drums and Phil Upchurch on bass add admirable support, but Pops’ guitar anchors the recording, from the country blues licks of “When I’m Gone,” to the rockabilly rhythm/lead combo of “He’s All Right.” By the concert’s end, the Staple Singers had defined the meeting place of the African-American church and the American civil rights movement.

The Staples were devastated by the death of their friend and hero Martin Luther King in April 1968, but by July they’d recovered enough to sign with Stax Records, where Al Bell and Steve Cropper helped them continue on their path toward gospel-infused pop music.

Bell also wanted to produce solo records for Pops and Mavis. He and drummer Al Jackson, Jr., had the idea of making a record featuring three Stax guitarists: Pops, Cropper, and Albert King. Though Pops’ tremolo guitar is overdubbed on a number of Jammed Together’s tunes, its full low-tuned mystery is reserved for the one Pops feature, “Tupelo.”

Guitarless in Muscle Shoals It wasn’t until Bell produced the Staple Singers in Muscle Shoals that the group had their first crossover hit, “Heavy Makes You Happy (Sha-Na-Boom Boom).” But it was their next one, “Respect Yourself,” that solidified the Staple Singers as crossover stars, hitting the pop charts at number 12.

For the follow-up, “I’ll Take You There,” Bell played a Jamaican record, “The Liquidator,” by the Harry J Allstars, for the Muscle Shoals crew. They lifted the intro practically intact and put their own spin on Aston and Carlton Barrett’s reggae rhythm. Though Mavis breathes, “Play, Daddy” before the guitar solo, Muscle Shoals guitarist Eddie Hinton performs it.

In Muscle Shoals Pops was not permitted to play guitar. Though the “Swampers” had utmost respect for his sound, his style was too idiosyncratic to fit into their well-oiled music machine, though the spirit of Pops’ sound remains in Barry Beckett’s spooky electric piano and the soulful guitars of Jimmie Johnson and Eddie Hinton. Pops wasn’t happy about not playing on the sessions, but his feathers were smoothed when “I’ll Take You There” became a number one pop and R&B single.

These secular successes brought some expected backlash from the gospel community, who took the Staples’ political and pop songs as a sign they were turning their backs on the church. Pops felt the group was still doing the Lord’s work by bringing messages of hope, pride, and unity to the black community. The group played a prominent role in Stax’s celebration of black pride, the 1972 Wattstax concert, and was featured on the best-selling recorded documentary that followed.

Staples’ guitar was absent on the next round of Muscle Shoals sessions as well. Despite being a retread of “I’ll Take You There,” “If You’re Ready (Come Go with Me)” gave them another top 10 hit in 1973. “Touch a Hand (Make a Friend)” followed it up the charts later that year. The album, Be What You Are, also contained a track called “Heaven,” featuring acoustic and electric guitar (and a solo) from another Staples fan: Jimmy Page.

The Weight Part II The Staples left a failing Stax Records in 1975, but were quickly signed by Warner Brothers, who paired the group with Curtis Mayfield as producer. Mayfield was working on a soundtrack for Let’s Do It Again, a movie featuring Bill Cosby and Sidney Poitier, and wanted the Staples to sing the title song. Initially put off by its sexual innuendo, Pops was brought around by his respect for Mayfield and his daughters’ enthusiasm, leading to yet another huge hit.

In 1976 Martin Scorsese convened a special shooting session of the Staple Singers and the Band singing “The Weight.” The Staples had covered the song back in 1968, weeks after the Band’s first album, Music from Big Pink, was released. The group had been unable to play the concert filmed for the Last Waltz, but the Band considered the Staples’ vocal sound a huge influence on their own vocals and harmonies, and wanted them in the movie.

The late ’70s saw many bands struggling with the rise of disco, and the Staple Singers—now simply known as the Staples—were likewise caught in the conundrum. Chasing trends with tunes like “Let’s Go to the Disco” was no answer. They returned to Muscle Shoals in 1978 in hopes of recapturing some of their original magic, but cutting a bunch of dance tracks, even with the Swampers, was no help.

Working in Allen Toussaint’s studio with Meters bassist George Porter and arranger Wardell Quezergue also failed to reignite the Staples’ success. In 1984, on yet another label, the Staples had a new flirtation with the R&B charts thanks to a recording of the Talking Heads tune “Slippery People.” This led to Pops acting in Talking Heads frontman David Byrne’s movie True Stories. Other acting jobs followed: Barry Levinson’s film Wag the Dog and the Chicago production of Bob Telson’s gospel-based musical, The Gospel at Colonus. Finally, Mavis left the group for a solo career, and Pops began his own solo flight.

The Staple Singers with Stax label mates Booker T. & the MG’s in a late 1960s rehearsal.

Solo Staples Virgin Records subsidiary Point Blank was signing a spate of blues artists in the late ’80s, including Albert Collins and John Lee Hooker. At the behest of Hooker’s booking agent, they signed Pops.