|

As you can imagine, based on the warped sounds that emanate from so many EHX devices, Matthews’ story and the saga of Electro-Harmonix is a long, twisted tale that could only happen in the world of rock ’n’ roll.

From Kool-Aid Stands to Guild Foxey Lady Fuzzes

Matthews’ tale begins in New York City. “Ever since I was a kid, I was always into business— y’know, big money,” he says. “On the street in the Bronx, my mother first set me up with one of those stands to sell drinks. And our drinks were better because she helped me make real fresh juice as opposed to Kool-Aid or . . . stuff out of the sewers. I was just always into hustling and business as a kid. I also started playing piano when I was 5. It was classical, and I quit in the fourth grade."

Then came rock ’n’ roll. “I really got into it in college, but I didn’t know what the hell I wanted to do. My father said, ‘Well, you’ve got to have a profession.’ So, for no particular reason, I registered in electrical engineering. Between the electrical engineering, being into business, and being a musician, it was sort of natural for me to fall into this industry.”

Even as he was beginning this free-fall toward immortality in the pantheon of stompbox pioneers, Matthews got married and started to feel his literal mortality. “I got married young,” he says, “and my first wife told me I should work toward a goal. So I took that to the ultimate extreme—this was right at the beginning of Electro-Harmonix—and that goal was . . . to whip death. In my own lifetime.”

Back up. Weren’t we talking about effects pedals here? Rock ’n’ roll?

“If you look at each generation,” says Matthews, “they live longer than the last. I thought if you look ahead a hundred years, people will be regularly living to 100, 120, maybe even 200 years. A thousand years from now, they’ll cross the threshold where they just won’t die.”

|

Though he’d had his head in the electrical engineering space, Matthews couldn’t stay out of the rock world for long. The road to becoming a guitar-gear kingpin began with Matthews wanting to get back into playing music—which he had given up temporarily to take a straight job as a salesman for IBM. “You know how it is,” he says, “once it gets into your blood, you want to get back. You like the people digging you. You want to be a star. The ladies, the money, the glory. Basically the glory, y’know.” [Laughs.]

As Matthews rediscovered his rock roots, he also witnessed the renaissance that was unfolding around him in Greenwich Village. He gigged around the area and got close to some of the biggest players of the day, including Jimi Hendrix. The two met when the future Strat master was working as a sideman for Curtis Knight and the Squires, and Matthews says he encouraged Hendrix to develop his vocal abilities so he could move on to establish his own career. Hendrix apparently did so, and soon went off to England as Matthews went his own way.

The future pedal guru was in and out of day jobs and night gigs, but through it all he clung to the dream of breaking out. And slowly but surely, Matthews found ways to make money from music.

“My relationship with Hendrix had really no effect on my work,” he says, “because I wanted to start playing again. At that time, ‘Satisfaction’ was a big hit. It was Number One for 13 weeks, I think. Everybody wanted a fuzz tone, but Maestro couldn’t make them fast enough. I started building fuzz tones to make some quick money so I could quit my day gig at IBM and play music again.”

Matthews and then-partner Bill Berko, an audio repairman who claimed to have his own custom fuzz circuit, outsourced construction of the units and sold them to Guild, which ended up labeling them “Foxey Lady” in an effort to capitalize on Hendrix’s rising popularity.

But for Matthews, starting his own business was the real dream. “Back in ’68, I worked with this brilliant guy, Bob Myer at Bell Labs, trying to design a distortion-free sustainer, so everybody could sound like Jimi Hendrix. The LPB-1, the Linear Power Booster, started the business.”

As Myer developed the LPB-1, he found that it wasn’t difficult to create a circuit that sensed the lower volume and turned up the gain as a note died out. The real difficulty was decreasing the gain fast enough so that there weren’t horrendous popping sounds when a new note was struck.

In short order, Matthews learned a few things about the guitar business. “I started out selling the LPB-1s via mail order,” he recalls. “You can’t sell direct as a manufacturer and at the same time sell to stores [laughs], because a store isn’t going to buy something that competes with them. What I did was advertise at full list, and the stores would still get their discount. I didn’t make a profit, but it basically paid for my advertising. As such, I was able to advertise as a big company, which gave me a big presence and built up demand at the stores.”

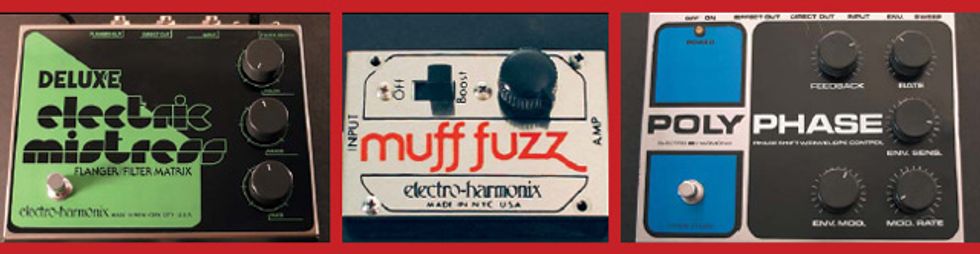

Mistress, a Muff Fuzz, and a Polyphase. Photos by Tom Hughes

Pi in the Sky—and Everywhere Else

If there’s one pedal that EHX is most known for, it’s the Big Muff Pi. Myer and Matthews came up with its design in 1969. “When I came out with the Big Muff, I spent a lot of time shaping the cascading gain stages, which gave a super-long sustain. I also worked a lot with the filters to get the notes to sound less raspy and more sinusoidal and smooth. That’s how the Big Muff got its long, violin-like sustain, because the filters filtered out the harsh cross products.”

From there, the Big Muff Pi sold like, er, hotcakes. “I brought the first ones up to Manny’s Music and Henry [Goldrich], the owner at that time, told me that Hendrix just bought one,” Matthews recalls. “Carlos Santana bought a Big Muff mail order. He sent in a check—a Carlos Santana check, y’know, with his drums and bongos on it— and Carlos Santana stationery. We still have copies of that here.”

At that point, it seems the floodgates had opened fully—both crazy product names and off-the-wall design ideas were flowing freely. “One of the other ideas I had around that time was a guitar that had a speaker that was in a ceramic case that screwed into the guitar. So the guitar output would go to an amp, but part of it would bleed into a separate amp that would feed the signal back into the ceramic speaker that would give you some actual real feedback right into the guitar.”

As for the funky names on Electro- Harmonix gear, the story behind them is predictably circuitous. “What happened with the Big Muff is that, we had this treble booster, our bass booster, and then we had a fuzz. It had a muffled sound, so I called it the Muff Fuzz. Later on, when we developed the superior distortionsustainer unit, because we already had the Muff, I called it the Big Muff. That’s how it came about—it evolved. But I also like those names with a double meaning. And the Bad Stone was just trying to play off the name of the Rolling Stones and Bob Dylan’s “Like a Rolling Stone” hit. I came up with most all the names.”

With Hendrix and Santana using Big Muffs at the height of their powers, it’s no wonder the devices did so well. “We were building 3000 Big Muffs a month,” Matthews says. “We quickly followed it with some variations. We had a little treble booster, a bass booster, a Little Muff . . . and there wasn’t that much competition.”

But that didn’t last long. “MXR came along and they were a big competitor. We battled. They came on big with the Phase 90, and we were really working hard to come out with a phase shifter. As we were working on it, the problem was that there was some feedback. But that feedback turned out sounding good, so we captured it. You could have regular phasing or, with the flick of a switch, you could have feedback and get this really edgy sound. The feedback would sharpen the notes. A lot of our competitors, they hate noise. Anything that has noise has to be taken out. They’ll work their asses off filtering out every ounce of noise to the point where they filter out the feeling. I mean, playing music is really . . . it’s getting out feelings. So I always want to leave the feeling in.”

A Fistful of Firsts to Finance Immortality

For decades now, stompboxes from a plethora of manufacturers have been available in such variety that we take them for granted. But Matthews says it was his company that pioneered distortion, delay, modulation, and even sampler pedals. “The old Electro- Harmonix, we had great sounds—we were very innovative. We were first with a lot of things. I mean, we were first with a flanger that wasn’t something you created for the studio. We were first with analog delay. We were first with low-cost samplers—the Instant Replay and Super Replay. I took those to Ikutaro Kakehashi, Roland’s founder. He liked the technology. He flew me to Japan and wanted me and David [Cockerell, designer of the Small Stone] to be part of Roland. But his chief engineer thought they could do it themselves, so I made a deal with Akai. Kakehashi told me it was his biggest mistake, because Akai samplers ruled the industry.”

While Matthews may come across as pretty bold, he’s also honest about some of the company’s early setbacks. “Instead of really focusing on the chassis and the mechanical construction, we moved on to the next thing. A lot of the early pedals were flimsy and broke down easily. That was not our bag, at that time. That was back in the ’60s and ’70s. Now, of course, our products are built rock-solid.”

Matthews continued his overall quest for immortality in the early 1970s with a trip to Haiti and dalliances with the powers of mental telepathy. Fortunately, the quest also involved making effects pedals. Lots and lots of effects pedals.

“In order to whip death, I had to grow the business,” Matthews explains. “Double it in size every year. If we missed that goal and only grew by 50 percent, we’d have to make it up the next year. Again, it was back to my ex-wife and this goal—it was absurd—to whip death in my own lifetime. I was always interested in expanding, in coming out with more stuff so I could make more money, hire more engineers, and have a great scientific think tank that would help me eventually whip death.” Considering the time period, it’s easy to assume this exceedingly lofty goal was all some sort of flower-power pipe dream. But Matthews says, “I wasn’t a hippie, I was a loner. I had long hair, but I wasn’t really in any group. I was just into making money, having fun, playing in the group.”

Mistress, a Muff Fuzz, and a Polyphase. Photos by Tom Hughes

Pi in the Sky—and Everywhere Else

If there’s one pedal that EHX is most known for, it’s the Big Muff Pi. Myer and Matthews came up with its design in 1969. “When I came out with the Big Muff, I spent a lot of time shaping the cascading gain stages, which gave a super-long sustain. I also worked a lot with the filters to get the notes to sound less raspy and more sinusoidal and smooth. That’s how the Big Muff got its long, violin-like sustain, because the filters filtered out the harsh cross products.”

From there, the Big Muff Pi sold like, er, hotcakes. “I brought the first ones up to Manny’s Music and Henry [Goldrich], the owner at that time, told me that Hendrix just bought one,” Matthews recalls. “Carlos Santana bought a Big Muff mail order. He sent in a check—a Carlos Santana check, y’know, with his drums and bongos on it— and Carlos Santana stationery. We still have copies of that here.”

At that point, it seems the floodgates had opened fully—both crazy product names and off-the-wall design ideas were flowing freely. “One of the other ideas I had around that time was a guitar that had a speaker that was in a ceramic case that screwed into the guitar. So the guitar output would go to an amp, but part of it would bleed into a separate amp that would feed the signal back into the ceramic speaker that would give you some actual real feedback right into the guitar.”

As for the funky names on Electro- Harmonix gear, the story behind them is predictably circuitous. “What happened with the Big Muff is that, we had this treble booster, our bass booster, and then we had a fuzz. It had a muffled sound, so I called it the Muff Fuzz. Later on, when we developed the superior distortionsustainer unit, because we already had the Muff, I called it the Big Muff. That’s how it came about—it evolved. But I also like those names with a double meaning. And the Bad Stone was just trying to play off the name of the Rolling Stones and Bob Dylan’s “Like a Rolling Stone” hit. I came up with most all the names.”

With Hendrix and Santana using Big Muffs at the height of their powers, it’s no wonder the devices did so well. “We were building 3000 Big Muffs a month,” Matthews says. “We quickly followed it with some variations. We had a little treble booster, a bass booster, a Little Muff . . . and there wasn’t that much competition.”

But that didn’t last long. “MXR came along and they were a big competitor. We battled. They came on big with the Phase 90, and we were really working hard to come out with a phase shifter. As we were working on it, the problem was that there was some feedback. But that feedback turned out sounding good, so we captured it. You could have regular phasing or, with the flick of a switch, you could have feedback and get this really edgy sound. The feedback would sharpen the notes. A lot of our competitors, they hate noise. Anything that has noise has to be taken out. They’ll work their asses off filtering out every ounce of noise to the point where they filter out the feeling. I mean, playing music is really . . . it’s getting out feelings. So I always want to leave the feeling in.”

A Fistful of Firsts to Finance Immortality

For decades now, stompboxes from a plethora of manufacturers have been available in such variety that we take them for granted. But Matthews says it was his company that pioneered distortion, delay, modulation, and even sampler pedals. “The old Electro- Harmonix, we had great sounds—we were very innovative. We were first with a lot of things. I mean, we were first with a flanger that wasn’t something you created for the studio. We were first with analog delay. We were first with low-cost samplers—the Instant Replay and Super Replay. I took those to Ikutaro Kakehashi, Roland’s founder. He liked the technology. He flew me to Japan and wanted me and David [Cockerell, designer of the Small Stone] to be part of Roland. But his chief engineer thought they could do it themselves, so I made a deal with Akai. Kakehashi told me it was his biggest mistake, because Akai samplers ruled the industry.”

While Matthews may come across as pretty bold, he’s also honest about some of the company’s early setbacks. “Instead of really focusing on the chassis and the mechanical construction, we moved on to the next thing. A lot of the early pedals were flimsy and broke down easily. That was not our bag, at that time. That was back in the ’60s and ’70s. Now, of course, our products are built rock-solid.”

Matthews continued his overall quest for immortality in the early 1970s with a trip to Haiti and dalliances with the powers of mental telepathy. Fortunately, the quest also involved making effects pedals. Lots and lots of effects pedals.

“In order to whip death, I had to grow the business,” Matthews explains. “Double it in size every year. If we missed that goal and only grew by 50 percent, we’d have to make it up the next year. Again, it was back to my ex-wife and this goal—it was absurd—to whip death in my own lifetime. I was always interested in expanding, in coming out with more stuff so I could make more money, hire more engineers, and have a great scientific think tank that would help me eventually whip death.” Considering the time period, it’s easy to assume this exceedingly lofty goal was all some sort of flower-power pipe dream. But Matthews says, “I wasn’t a hippie, I was a loner. I had long hair, but I wasn’t really in any group. I was just into making money, having fun, playing in the group.”

Not Your Everyday Big Muff Pi: When Premier Guitar was brainstorming pedal manufacturers to approach about being part of this special four-cover/collectible-custom-pedal issue, Electro-Harmonix was a no-brainer because of its place in stompbox history and the quality of its products. Here, senior quality control technician Zaida Sojos tests one of the custom PG “Pedal Issue” units seen on select November 2010 issues.

The Russian Connection

If you look back at EHX boxes over the years, they’ve all got a pretty similar look—brushed, folded-metal enclosures with bright color schemes. That was until Matthews ceased US production in the mid ’80s and hooked up with Russian producers to both export Russian-made pedals and get into the tube trade. “In 1979, we were doing a lot of business with Communist countries. I got a letter inviting us to one of the first-ever trade shows in Moscow open to consumer companies,” Matthews remembers. “This was a huge trade show with exhibitors from the US, Germany, and Japan. I thought ‘I gotta go.’

“But, as it turned out, no one in Russia had any money. In the end, we got no orders. The show was a failure. Russia wanted our stuff, but they had no money. What could I buy from Russia? They needed money. I decided to try to buy integrated circuits, Russian integrated circuits— these cheap, jellybean ICs that would cost 15 to 20 cents apiece. When I went over to visit, I had to go to the Ministry of Electronics to talk business. There I saw, hanging on the wall, vacuum tubes. I said ‘Send me some samples,’ which I got a month later. I took them out to Jess Oliver, who worked at Ampeg and designed most of the great Ampeg amps. He said the tubes were good, so I switched from wanting to buy ICs to vacuum tubes.”

As luck would have it, this gambit paid off pretty well. “I was able to grow a lot faster. I was able to start a good business with the ICs, but because I called on people in the music industry—and because they knew me—they would try the tubes. Now I own the factory. So the ’79 trade show was a failure, but it got me into vacuum tubes and the tubes got me back into Electro-Harmonix. And that got us back into the pedals. I partnered with a military company that repackaged the Big Muff and Small Stone.”

If you’ve ever wondered what the deal is with the austere-looking black versions of the Big Muff Pi and Small Stone, they’re the result of this Russian connection. They bore the Sovtek brand name, and they had yellow lettering (there were also green-and-black and black-and-red versions at various times). However, by the mid ’90s, EHX had begun reissuing original designs, and in 2002 they began adding new designs to the lineup once again. And as recent offerings like the Ring Thing (reviewed July 2010), the Cathedral Stereo Reverb (Feb. 2010), and POG prove, the company is clearly in the midst of a second golden age.

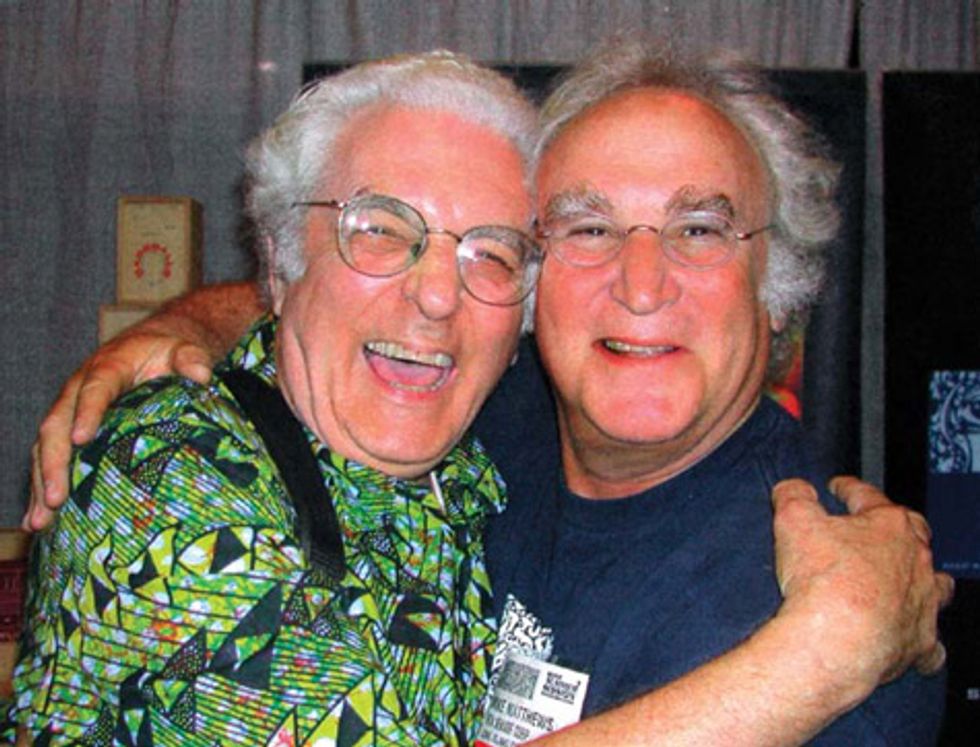

Carousing with the Competition: Friend and fellow effect pioneer

Bob Moog (left) stops by to say hello to Matthews circa 2003.

The Irony of Immortality

As far as the current boutique pedal boom, Matthews says he welcomes the competition. “We have the Electro-Harmonix name and the history. And, instead of having one or two of these companies to compete with, we have one or two hundred—which actually makes it easier. But most of these guys, y’know, they’re into analog stuff only. They’ll bring out their own versions of various flangers or distortion pedals. They come up with some good stuff, but it’s too expensive. I’m happy for the competition— they compete with each other.”

As for what’s ahead for Electro-Harmonix, Matthews is blunt when asked if he’ll offer up a peek. “No. But what’s really hot right now—what we’ve sold out of—is the Freeze (reviewed this issue). If you hold down the momentary switch, it’s constantly taking a sample—so whatever you’ve played is frozen and sustained. And you can play on top of that and release that switch and it dies out. It’s very musical.”

And then he launches back to the past, back to his original goal of immortality. On one hand, he seems to have given up the goal. On the other, it seems he’s attained it through the role he played—and continues to play—in both the history of musical instrument manufacturing and guitar music.

“In the late ’70s,” Matthews confides, “I had too many problems all at once. It was overwhelming. I was expanding into too many things and I collapsed. Since we reformed, I’ve become more conservative. Now I’m much stronger financially and more patient—and not trying to whip death. I’m just trying to make money and have fun and take things slower.”

Not Your Everyday Big Muff Pi: When Premier Guitar was brainstorming pedal manufacturers to approach about being part of this special four-cover/collectible-custom-pedal issue, Electro-Harmonix was a no-brainer because of its place in stompbox history and the quality of its products. Here, senior quality control technician Zaida Sojos tests one of the custom PG “Pedal Issue” units seen on select November 2010 issues.

The Russian Connection

If you look back at EHX boxes over the years, they’ve all got a pretty similar look—brushed, folded-metal enclosures with bright color schemes. That was until Matthews ceased US production in the mid ’80s and hooked up with Russian producers to both export Russian-made pedals and get into the tube trade. “In 1979, we were doing a lot of business with Communist countries. I got a letter inviting us to one of the first-ever trade shows in Moscow open to consumer companies,” Matthews remembers. “This was a huge trade show with exhibitors from the US, Germany, and Japan. I thought ‘I gotta go.’

“But, as it turned out, no one in Russia had any money. In the end, we got no orders. The show was a failure. Russia wanted our stuff, but they had no money. What could I buy from Russia? They needed money. I decided to try to buy integrated circuits, Russian integrated circuits— these cheap, jellybean ICs that would cost 15 to 20 cents apiece. When I went over to visit, I had to go to the Ministry of Electronics to talk business. There I saw, hanging on the wall, vacuum tubes. I said ‘Send me some samples,’ which I got a month later. I took them out to Jess Oliver, who worked at Ampeg and designed most of the great Ampeg amps. He said the tubes were good, so I switched from wanting to buy ICs to vacuum tubes.”

As luck would have it, this gambit paid off pretty well. “I was able to grow a lot faster. I was able to start a good business with the ICs, but because I called on people in the music industry—and because they knew me—they would try the tubes. Now I own the factory. So the ’79 trade show was a failure, but it got me into vacuum tubes and the tubes got me back into Electro-Harmonix. And that got us back into the pedals. I partnered with a military company that repackaged the Big Muff and Small Stone.”

If you’ve ever wondered what the deal is with the austere-looking black versions of the Big Muff Pi and Small Stone, they’re the result of this Russian connection. They bore the Sovtek brand name, and they had yellow lettering (there were also green-and-black and black-and-red versions at various times). However, by the mid ’90s, EHX had begun reissuing original designs, and in 2002 they began adding new designs to the lineup once again. And as recent offerings like the Ring Thing (reviewed July 2010), the Cathedral Stereo Reverb (Feb. 2010), and POG prove, the company is clearly in the midst of a second golden age.

Carousing with the Competition: Friend and fellow effect pioneer

Bob Moog (left) stops by to say hello to Matthews circa 2003.

The Irony of Immortality

As far as the current boutique pedal boom, Matthews says he welcomes the competition. “We have the Electro-Harmonix name and the history. And, instead of having one or two of these companies to compete with, we have one or two hundred—which actually makes it easier. But most of these guys, y’know, they’re into analog stuff only. They’ll bring out their own versions of various flangers or distortion pedals. They come up with some good stuff, but it’s too expensive. I’m happy for the competition— they compete with each other.”

As for what’s ahead for Electro-Harmonix, Matthews is blunt when asked if he’ll offer up a peek. “No. But what’s really hot right now—what we’ve sold out of—is the Freeze (reviewed this issue). If you hold down the momentary switch, it’s constantly taking a sample—so whatever you’ve played is frozen and sustained. And you can play on top of that and release that switch and it dies out. It’s very musical.”

And then he launches back to the past, back to his original goal of immortality. On one hand, he seems to have given up the goal. On the other, it seems he’s attained it through the role he played—and continues to play—in both the history of musical instrument manufacturing and guitar music.

“In the late ’70s,” Matthews confides, “I had too many problems all at once. It was overwhelming. I was expanding into too many things and I collapsed. Since we reformed, I’ve become more conservative. Now I’m much stronger financially and more patient—and not trying to whip death. I’m just trying to make money and have fun and take things slower.”