Collings SoCo Deluxe Custom with a flamed maple top, Brazilian rosewood fretboard with “broken glass” inlays, and a Bigsby B7 vibrato. |

Taking what those who now work with him call an “Energizer Bunny-like” drive to create, Collings built his first guitar in 1974 after leaving medical school and taking some time off to figure out what he wanted to do with his life. He was working in a machine shop when the bright idea of making guitars came up. Naturally, his parents thought he should continue with school and become a doctor.

“I liked the science part of that,” says Collings in a recent interview, “but I like the science of manufacturing or making things more. So working on a motorcycle or a car, building a guitar, whatever it might be, that’s more my thing. And to this day, I just love that part of it.”

Collings’ quest gradually became about more than just making guitars one-by-one on his own. His long-time business manager, Steve McCreary, explains it this way: “We have a great crew that works every day to accomplish Bill’s original challenge—which was to have a production shop that builds the finest, handmade-quality instruments. It’s quite a challenge, let me tell you. Our guitars are based on his guitars when he was a one-man shop, and they weren’t really designed to be production guitars, so it’s a tremendous amount of work.”

Starting Small, But in a Big Way

Songwriter Lyle Lovett, one of Collings’ strongest supporters, recalls their first meeting in 1978. Lovett was at a Houston club listening to a songwriter by the name of Rick Gordon, and he was intrigued by Gordon’s flattop. “He was playing a guitar that looked unusual to me, it looked like nothing I’d ever seen. It was a Martin 000-shaped cutaway with wood binding, and I thought, What kind of Martin is that?”

Lyle Lovett onstage with his 2008 cherry-sunburst D2 flattop. “Bill’s guitars just get better and better. You can’t pick one up that you don’t like.” Lovett also plays a 1992 CJ. Photo by Michael Wilson

The plain headstock didn’t help, so Lovett made it a point to ask Gordon about it during his break. That was when he first heard the name Bill Collings. Having a Martin D-35 in need of a fret job, Lovett contacted Collings to do the work. “Bill said, ‘Sure, come on over,’ just like that.” Lovett continues, “He was living and working in Houston at the time. He lived in a two-bedroom apartment—one bedroom was where he lived and the other was his workshop. I remember getting to his apartment at about two in the afternoon, and I didn’t leave until about nine that night. He fixed dinner for me, showed me every piece of wood he had in his shop, showed me guitars he was building and working on. And before I left that day, I ordered my first Collings guitar.” It was a dreadnought with a German spruce top and Indian rosewood back and sides, and it was his main stage guitar for years. Lovett also played it on all of his early recordings. “It turned out to be #39, the thirty-ninth guitar Collings ever made, and I still have it.”

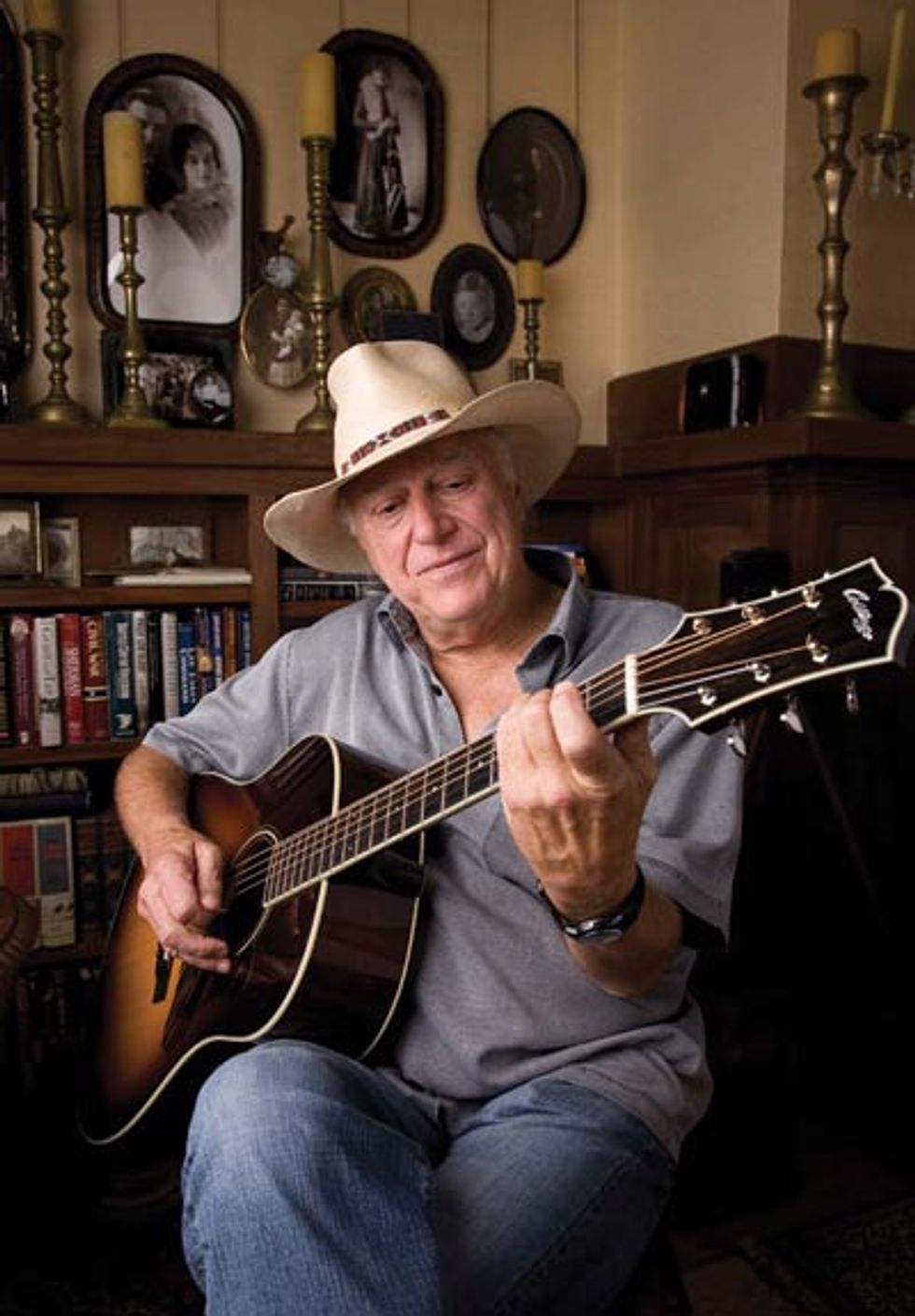

Jerry Jeff Walker at ease with his sunburst 2008 CJ. “The worst one he’s gonna make is still gonna be wonderful,” he says of Collings’ instruments. Walker’s first Collings was a 1992 13-fret C10, and he also has a sunburst 2009 01A in his collection. Photo by Rick Patrick |

The All-Important Boat That Didn’t Float

In the early ’80s, Collings decided to move to California but only made it as far as Austin, and that’s where he’s been ever since. He shared shops with luthiers Tom Ellis and Mike Stevens for a few years before moving to a small, one-stall garage shop on his own. In 1989, he hired his first employee, Bruce Van Wart, who is still with Collings. Among other responsibilities, Van Wart chooses all the wood for the flattop guitars and the ukuleles.

The funny part is that Van Wart initially connected with Collings over a boat. “We had a mutual friend, and he said, ‘You need to meet this guitar builder, because he wants to know about building this boat’—because I used to do that. So, I went over to the shop, he showed me his boat plans, and we talked. He never built the boat, but we had fun.” Van Wart didn’t see Collings again until one of his guitars needed some work. “I worked for a weekend or two in trade for him doing a neck reset on my Martin, making some stairs going up into the loft in the shop, helping him build a spray booth. I was doing house remodels at the time, and that was pretty slow down here. He said, ‘Hey, do you wanna work for me?’ and I said, ‘Okay!’”

Collings and Van Wart worked together for several months, “Then, all of a sudden, there were five people. So it got pretty exciting.” Van Wart explains, “Everybody had their routine and we had to kind of dance around each other because it was a real small shop. The first shop I worked with Bill in, the spray booth was in the building next door, so when it was raining you had to run with the guitars with plastic over them to the other building. That was kinda fun.”

The exterior of the Collings Guitars workshop in Austin, Texas.

Collings moved his operation once and expanded twice before moving into the current building. Now, approximately 70 employees work to build flattops, archtops, mandolins, ukuleles, and electric guitars.

Wildfire Word of Mouth

Once the company was set up in Austin, things really took off and Collings began to get a reputation as a quirky genius. It’s not just guitars that Collings loves to work on. He’s got a real thing for cars and motorcycles, too. McCreary says he’s notorious for being out working on a car and coming into the shop for something, getting distracted and starting to work on a guitar with his hands still covered in oil from the car. “We call him Collings, the One and Oily. To him it’s all kinda the same thing—it’s all ‘How do you get the most you can get out of this thing?’”

Jimmie Vaughan and his AT16 Custom archtop (left) with Bill Collings and his 1932 “five-window” Ford.

McCreary says they’ve never really done any marketing, and not much advertising. “We’ve always been kind of under the radar. We’ve never been able to make more than we can sell, so we’ve never had a marketing department. It’s all been pretty organic, the growth over the past several years.” Subtle things have added to the buzz, though. Things such as actor/director/ musician Christopher Guest’s character using a Collings guitar and mandolin in the wonderful “mockumentary” A Mighty Wind. Guest also recently used a Collings to perform music from both A Mighty Wind and This Is Spinal Tap on the Unwigged and Unplugged Tour with Michael McKean and Harry Shearer. Guest’s Collings addiction seems to be fairly serious. “I got my first one . . . I guess it was about 20 years ago. And then I bought a mandolin, and then another guitar, then another mandolin, then another guitar, and then another guitar. And I’ve been playing them since then.”

Collings’ guitars gained a reputation for being simply spectacular, and if not perfect, they started to come as close as humanly possible. “You can’t do it anyhow,” says Collings, “so you just try to come as close as you can. Can you pick the perfect piece of wood? No, but you can get really close. Can you make it the perfect thickness? No, but you can get really close. Can you scientifically do it? No, but you can get close. So we do it all—buy the best wood, intuitively making a judgment on it, weighing it, banging on it, and roughly coming to the right thickness. We do whatever we can.” And he’s adamant in that quest for perfection. “Every day we try to make a better guitar, every day. And every day there are tops sitting in bins that will be braced soon, and they will all become a better guitar than yesterday. You’re trying to reach for more, trying to do better, not trying to do the same. A lot of companies are trying to do the same, and that’s okay—that’s their deal. We’re trying to stretch that. Our goal is a little more.”

The Art and Science of Wood Selection

Wood selection is Van Wart’s area, and his philosophy is a mix of exacting standards, intuition, and the experience of having thousands of board feet of wood pass through his hands over the past two decades. “What you’re trying to do is maximize the piece of wood that you have. It’s not a perfect world and every piece of wood is different, so you’re just trying to make that piece of wood as excitable as you can get it. You have to do it individually, each piece is different.” As far as top woods are concerned, “I’m not looking for so many grains. You can have a piece of wood that has pretty wide grain that can be just as good as a piece of wood that has really tight grain. Sometimes if the grain gets too tight, it adds too much weight.”

Like many acoustic builders, Collings has tried some different woods in recent years, but he feels pretty strongly about staying close to traditional woods. “Every time we think they will work for us, there’ll be a reason to not use them. Say, ziricote–you get it to the right thickness and it’s cardboard. You get into all these alternatives and, well, there’s a reason they aren’t traditional woods. The reason is that they’re not as good as what we were using. Cocobolo—man, that is the worst guitar wood on the planet! I can’t understand why people use it! It’s heavy, everything’s wrong, but people use it. Is it good guitar wood? No. Not to me. I’ve tried to find different woods that will work. Cherry will work, it’s okay. Walnut? It’s okay. Maple? Real prevalent, always made a good guitar—not the best for acoustics, but good for archtops and violins. And it’s real accessible, real re-growable. Good wood. Traditional wood. We use it. There’s a market for different stuff, but that’s really why we kind of stick to a certain little group—because it works and it’s going to last.”

Love Begets Love

While the wood choice at Collings may be on the traditional end of the spectrum, the process part of the equation is pretty dynamic. Never one to push paper or do more talking than working, Collings spends most of his days working in the shop, often in areas that have been struggling. “Last month I started working in the finish department, because they’ve been having a hard time for about a year. In fact, we were going to rename them the ‘unfinish department.’ So I went in there and found out that I had a hard time doing the job; every time I’d buff this guitar out, it’d get kicked back! And then I noticed that the inspectors had much better lights than we had, so I said, ‘We gotta get on the same playing field!’ So I tried to help them, to see why they can’t do the job like we’d expect. So that was a great month. Now I’m going to do the same thing in bodies.”

Dedicated Collings workers buffing acoustics (left) and electrics (right).

The single most important thing to Collings is the love of the work. Lovett, Walker, Guest, and National Fingerstyle Champion Pete Huttlinger are all impressed with how much every person in the Collings shop is crazy about guitars. “Well, that’s the deal,” Collings says emphatically. “You go over to China, and I know that factory isn’t run by guitar players. But that’s the reason they’re not ever going to rise to the top. Because your employees have to have the same feeling. They really do. It’s like making art without artists—how’s that going to happen? It’s not. Having the love, that’s going to help it get there. That’s pretty much it.”

Pete Huttlinger with his 1997 OM1. “When I sit down and grab any one of these guitars, I can find the music in there,” he says, “It’s always there for me.” Huttlinger’s first Collings was a mid-’90s OM2H, and he also uses a 2008 D1A. |

Never Afraid of a Musical Adventure

Collings built his first archtop in 1976. “The guitar thing,” he muses, “you want to do it all at once when you start. You want to do everything and you don’t know which direction to go.” His mile-wide curious streak led him down a few blind alleys as well. “There were banjo parts, and a finished banjo back in the early ’70s. I can’t say I’ll never do that again—make parts of it, maybe—but that’s actually not my deal.”

Mandolins seemed an obvious addition after carving the archtop guitars, and Collings says they make about 500 mandolins a year. At this point, they’re really happy with that number. Ukuleles, a more recent addition, were another obvious choice—especially from a historical perspective. “We started making ukes in a depression year,” he explains, “when we didn’t have enough work on guitars. I’ve heard that, many times in history, companies would do that. Martin did it, Gibson did it. When the economy was slow on guitars, they filled in with ukes.”

Ukes, however, are not nearly as easy to make as they look. “It’s a real instrument. You can buy a uke for $150, you can buy a guitar for $150, or $59, or $39. You can buy a uke for the same thing. There’s really no difference in the bottom line.” Collings shifts in his chair and pauses. “Actually, the same amount of work goes into a uke as goes into a guitar, so there you go—it’s almost the same. When we first started making ukes, they were a lot more than a guitar. The first 50 ukes took us more time than 50 guitars.”

According to Van Wart, that’s because ukes are a little fussier to make than guitars. Any mistake is magnified, because they’re so much smaller. “They take a lot of figuring out. It seems like you could just throw one together, but they take a lot of figuring. They’re really finicky.”

Most recently, Collings decided to try his hand at electric guitars. And, as always, he had in mind that careful balance between tradition and innovation. “If I came out and had a brand new thing—my own design that’s totally unique—it’s not going to make it, because the public won’t accept it. There are certain things they’re going to look at in certain areas. Say you have a Gibson influence, we make something on those lines, but we change it. We can’t drift that far from the spirit of that, because people want to relate to it. They’re going to relate my City Limits guitar to a Les Paul, but they’re not going to do it to any Les Paul—they’re going to do it to a vintage Les Paul. So we’ve got to put that style in there. Make the guitar around 8.25 lbs., make it play really great, have great humbuckers, and not be hollowed out, and blah blah blah. So you’ve got to pick the right wood, you’ve got to make it all work, and hope it’s accepted!”

Ever Onward

As you might’ve surmised by now, a vintage vibe is important to Collings. “To me, vintage—good vintage—is the stuff. That’s what I like, and hopefully that stuff is on my guitars.” He’s also got a pretty clear idea what people expect from the Collings brand. “If we had started with my 360 [solidbody] model, I don’t think it would have worked as well. But now, that little 360, people like it because it’s different than anything else.” (PG liked it too—we gave it a Premier Gear Award in the July 2009 issue.)

When the conversation is steered back to the recent economic downturn and how it has affected the company, Collings says it actually hasn’t hurt much. “Right now we have so much work. We’re just trying to get it out and keep our dealers somewhat happy if we can. But we’re so behind at the moment. We’ve just been slammed the past four to five months. Slammed. We did have three months where we weren’t slammed, but we noticed in late September and October it was back, big time.”

As for where his tendencies toward tireless tinkering will lead him next, Collings isn’t sure. “Usually things just happen,” he says. “We don’t plan it. We don’t do the model-of-the-month club and we don’t do anniversaries. We don’t do any of those things.” When nylon-string guitars come up, his interest is piqued. “I’m gonna do some of that. I should have done it already, but I haven’t. So you reminded me—thanks!”